Just the facts

Just the facts

respiratory anatomy and physiology

tests used to diagnose respiratory disorders in children

treatments and procedures used for children with respiratory problems

respiratory disorders that affect children and nursing interventions for each.

|

|

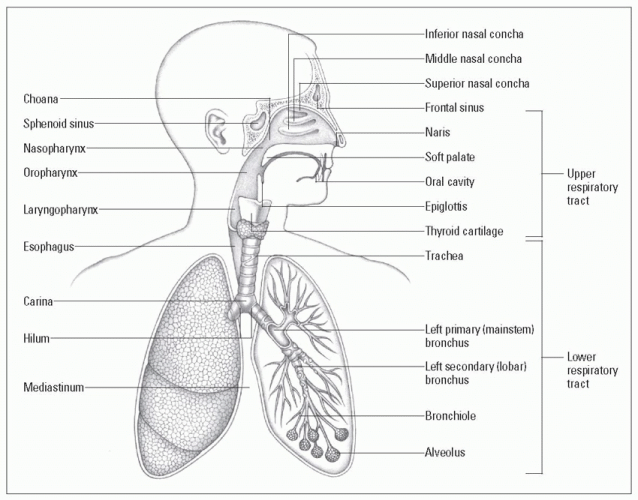

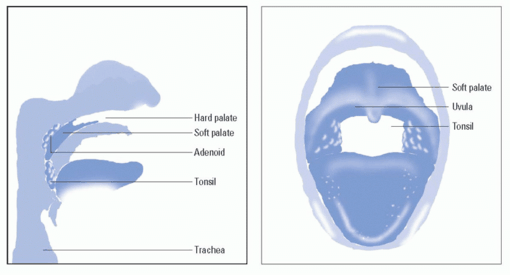

nose and nasal passages

mouth and oropharynx

pharynx

larynx.

|

|

trachea

bronchi

alveoli.

muscle. In infants, the cartilage is soft, making the airway more easily collapsible when the neck is flexed. A child’s trachea is higher than an adult’s and gives rise to two major bronchi: the right and the left. The right bronchus is shorter, wider, and situated more vertically than the left. Because of this, aspirated foreign bodies are more likely to become lodged in the right bronchus. (See Estimating tracheal diameter.)

|

process, the airway is further narrowed, increasing the airway resistance even more.

increased respiratory rate

retractions

nasal flaring

use of accessory muscles.

|

Oxygen-depleted blood enters the lungs from the pulmonary artery that arises from the heart’s right ventricle.

Oxygen-depleted blood enters the lungs from the pulmonary artery that arises from the heart’s right ventricle. Blood then flows through the main pulmonary arteries into the smaller vessels of the main bronchi, through the arterioles and, eventually, into the capillary networks that surround the alveoli.

Blood then flows through the main pulmonary arteries into the smaller vessels of the main bronchi, through the arterioles and, eventually, into the capillary networks that surround the alveoli. There, oxygen diffuses into the capillaries from the alveoli, and the oxygenated blood flows through progressively larger vessels, enters the main pulmonary vein, and flows into the left atrium.

There, oxygen diffuses into the capillaries from the alveoli, and the oxygenated blood flows through progressively larger vessels, enters the main pulmonary vein, and flows into the left atrium.

|

these respiratory muscles moves air into and out of the lungs. Normally, expiration is passive. (See Normal pediatric respiratory rates.)

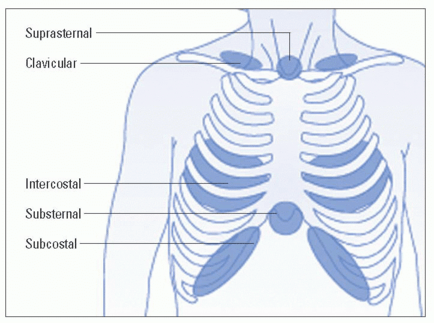

In mild distress, there are isolated intercostal retractions.

In moderate distress, there are subcostal, suprasternal, and supraclavicular retractions.

In severe distress, there are all of the retractions mentioned above along with accessory muscle use. (See Looking for retractions.)

|

|

|

Encourage small children to breathe deeply by asking them to pretend they’re blowing out candles or have them blow away a tissue.

Listen with the bell of the stethoscope for low-pitched sounds.

Listen with the diaphragm for higher pitched sounds.

|

Be honest about the painful part of the procedure. (For example, say, “This is going to hurt for a few seconds. It’s OK to be scared, but you’re going to do a great job and it’s going to be over very quickly.”)

Explain that only a small amount of blood will be taken, and that the child’s body will quickly make new blood to replace it. (Young children think they have a finite amount of blood and may have many misconceptions about what happens to them when some of that blood is removed.)

Allow the parent to comfort the child during the blood drawing. A parent’s presence reassures the child that nothing terrible will happen to him.

Give the child coping mechanisms. (For example, say, “Count to 5 and the hurting part will be over,” or, “Squeeze your mother’s hand if it hurts.”)

Praise the child for doing a good job regardless of how he reacts.

Comfort the child and apply a bandage as soon as the sample has been drawn; covering the site reassures the child that the hurting part is truly over.

|

Draw the blood sample into a heparinized syringe because unclotted blood is required.

Remove air bubbles from the sample to avoid altering the gas concentration.

Keep the blood sample on ice and transport it immediately to the laboratory.

|

|

Protect the child from radiation exposure by covering his gonads and thyroid gland with lead shields during the test.

Make sure the child holds still during the test and tell him that doing so is his special job. (You may need to assist the child to do so.)

A restrictive defect is one in which a person can’t inhale a normal amount of air; it may occur with chest wall deformities, neuromuscular diseases, or acute respiratory tract infections.

An obstructive defect is one in which something obstructs the flow of air into or out of the lungs; it may occur with such disorders as asthma, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and cystic fibrosis.

|

Note that results may not be accurate because the young child may have difficulty following the necessary directions.

Instruct the child and his parents that he should have only a light meal before the test.

Withhold bronchodilators and intermittent positive-pressure breathing therapy before the test.

|

Place the probe on a site with good perfusion, such as the finger, foot, or toe.

Periodically rotate sites for probe placement to prevent skin breakdown under the probe.

To ensure that the value is accurate, make sure the pulse reading on the pulse oximeter matches the child’s heart rate.

To determine the effectiveness of aerosol therapy, assess the patient’s breath sounds before and after treatment.

Monitor the patient’s tolerance of the procedure. An infant or young child may fight the MDI with spacer mask or the mask over his face during nebulizer therapy. (Calming techniques such as swaddling may be necessary.)

After teaching the child and his parents how to use the device correctly (which is necessary for optimal effectiveness), observe

while they demonstrate their technique; provide support and correct technique as needed. (See Using an MDI.)

Pressure-cycle ventilators, most commonly used in infants, deliver an indefinite volume of gas at a fixed inflation pressure.

Volume-cycled ventilators, most commonly used in children and adolescents, deliver a fixed volume of gas at whatever inflation pressure is necessary, up to a preset maximum.

It’s all relative

It’s all relative

Place the patient on a cardiorespiratory monitor and pulse oximeter during any form of assisted ventilation.

Obtain blood gases to monitor gas exchange and oxygenation status as ordered. (Prepare the child if an arterial puncture must be performed.)

For infants who have an ET tube or tracheostomy, suction the airway as needed to prevent occlusion with secretions.

Frequently assess breath sounds and watch for signs of ET tube or tracheostomy dislodgment. Make sure the ET or tracheostomy tube is appropriately secured to prevent dislodgment.

|

In patients who are mechanically ventilated, observe for signs of pneumothorax, such as respiratory distress, absent or decreased breath sounds on one side (the affected side), hypotension, and oxygen desaturation on pulse oximetry.

For patients receiving CPAP via nasal prongs, cut and place a cushioning dressing (such as Duoderm) over the edges of the nares and the tip of the nose to protect the skin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree