CHAPTER 2 Respiratory Disorders

Section One Acute Respiratory Disorders

Acute respiratory disorders are short-term diseases or acute complications of chronic conditions. They can occur once and respond to treatment or recur to further complicate an underlying disease process.

Atelectasis

Atelectasis

Collaborative Management

Management is aimed at preventing this condition in all patients. If atelectasis occurs and is left untreated, the affected lung area eventually may become infected, fibrotic, and functionless.

Deep-breathing and coughing exercises

Expand alveoli deep in the lungs and mobilize/clear secretions.

Nursing Diagnoses and Interventions

For Patients at Risk for Atelectasis

Ineffective breathing pattern

related to decreased lung expansion secondary to inactivity or omission of deep breathing

Nursing Interventions

Patient-Family Teaching and Discharge Planning

Patient-Family Teaching and Discharge Planning

Provide verbal and written information about the following:

Pneumonia

Pneumonia

Overview/Pathophysiology

Pneumonia in the immunocompromised individual

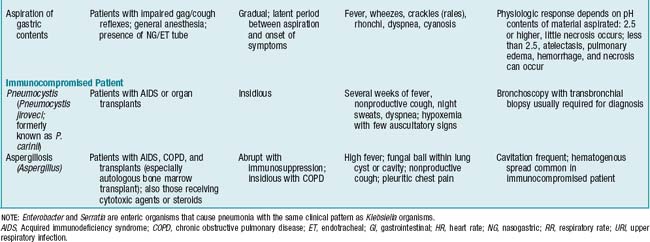

Immunosuppression and neutropenia are predisposing factors in the development of nosocomial pneumonias from both common and unusual pathogens. Severely immunocompromised patients are affected not only by bacteria but also by fungi (Candida, Aspergillus), viruses (cytomegalovirus), and protozoa (Pneumocystis jiroveci, formerly known as P. carinii). Most commonly, P. jiroveci is seen in persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease or in persons who are immunosuppressed therapeutically following organ transplants.

Assessment

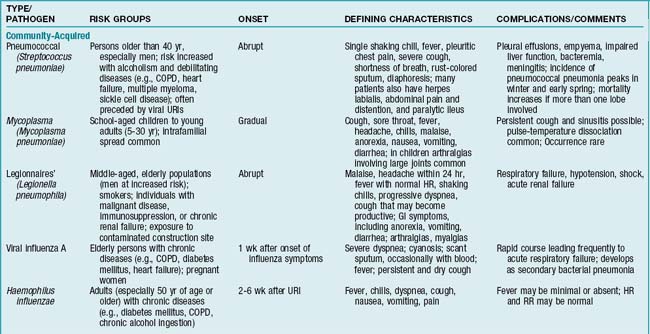

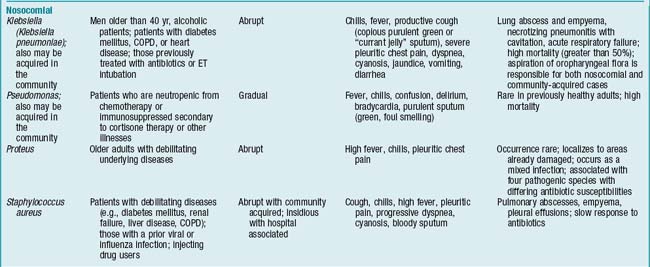

Findings are influenced by patient’s age, extent of the disease process, underlying medical condition, and pathogen involved. Generally, any factor that alters integrity of the lower airways, thereby inhibiting ciliary activity, increases the likelihood of developing pneumonia (TABLE 2-1).

Diagnostic Tests

Collaborative Management

O2 therapy

Administered when O2 saturation or ABG results demonstrate hypoxemia. Goal is to maintain PaO2 at 60 mm Hg or higher. Special consideration must be given to patients with chronic CO2 retention because their respiratory drive is stimulated by low/decreasing PaO2 levels and not by increasing PaCO2 levels as is normal. Therefore high concentrations of O2 can depress respiration in these patients so O2 is delivered in low concentrations initially, and O2 saturations or ABG levels are monitored closely. If O2 saturation or PaO2 does not rise to acceptable levels (greater than 92% or 60 mm Hg or more, respectively), fraction of inspired O2 (FIO2) is increased in small increments, with concomitant checks of ABG values or O2 saturations.

Percussion and postural drainage

Indicated if deep breathing and coughing are ineffective in mobilizing secretions.

Antitussives

Given in the absence of sputum production if coughing is continuous and exhausting to the patient.

Antipyretics and analgesics

Prescribed to reduce fever and provide relief from pleuritic pain or pain from coughing.

Nursing Diagnoses and Interventions

For Patients with Pneumonia

Nursing Interventions

Nursing Interventions

Deficient fluid volume

related to increased insensible loss secondary to tachypnea, fever, or diaphoresis

Nursing Interventions

Nursing Interventions

hr before deep-breathing exercises to control pain, which interferes with lung expansion. Scheduled analgesics also promote pain control. Support (splint) surgical wound with hands, pillows, or folded blanket placed firmly across site of incision.

hr before deep-breathing exercises to control pain, which interferes with lung expansion. Scheduled analgesics also promote pain control. Support (splint) surgical wound with hands, pillows, or folded blanket placed firmly across site of incision. Patient-Family Teaching and Discharge Planning

Patient-Family Teaching and Discharge Planning

Provide verbal and written information about the following:

Pleural Effusion

Pleural Effusion

Nursing Diagnoses and Interventions

Ineffective breathing pattern

related to decreased lung expansion secondary to fluid accumulation in the pleural space

Nursing Interventions

Patient-Family Teaching and Discharge Planning

Patient-Family Teaching and Discharge Planning

Provide verbal and written information about the following:

Pulmonary Embolism

Pulmonary Embolism

Overview/Pathophysiology

The most common pulmonary perfusion abnormality is pulmonary embolism (PE). PE is caused by passage of a foreign substance (blood clot, fat, air, or amniotic fluid) into the pulmonary artery or its branches, with resulting obstruction of the blood supply to lung tissue and subsequent collapse. The most common source is a dislodged blood clot from the systemic circulation, typically the deep veins of the legs or pelvis. Thrombus formation is the result of the following factors: blood stasis, alterations in clotting factors, and injury to vessel walls. A fat embolus is the most common nonthrombotic cause of pulmonary perfusion disorders (see p. 74).

Assessment

Signs and symptoms/physical findings

If infarction has occurred, fever, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis are common.

History and risk factors

Cardiac disorders

Atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction, rheumatic heart disease.

Diagnostic Tests

Cardiac troponin level

Elevated in PE as a result of right ventricular dilation and myocardial injury.

Chest x-ray examination

Initially findings are usually normal, or elevated hemidiaphragm may be present. After 24 hr, x-ray examination may reveal small infiltrates secondary to atelectasis that result from the decrease in surfactant. If pulmonary infarction is present, infiltrates and pleural effusions may be seen within 12-36 hr.