Respectful Interaction

Working with Adults

“From a young 30- or 40-year-old, I turned into an old 30- or 40-year-old. But once I was 59 I wasn’t too certain that the same magic as had been wreaked once I became a novice in other decades would continue to exert its power once I reached 60. Like Doris Day, I thought that “the really frightening thing about middle age is the knowledge that you’ll grow out of it.”

—V. Ironside1

Chapter Objectives

• Compare unique challenges of development in young and middle adulthood

• Discuss the meaning of work for adults

Who Is the Adult?

It may be true that of all the life periods, adulthood has been the least understood and least studied. A stereotype about adult life is that it is only a waiting period or holding place made up of work, establishing a family, or dealing with menopause or other physical changes on the way to retirement and old age. In reality, there is a wide variation in the type and timing of transitions and activities in adult life that is far richer than this stereotype suggests. For these reasons, it is important to examine some vital issues concerning life as an adult in today’s society.

Adulthood can be legally defined by chronological age or at the time a person begins to assume responsibility for himself or herself and others.2 It can also be defined by achievement of certain developmental tasks such as being independent; establishing long-term relationships; establishing a personal identify in a reflective way; finding a meaningful occupation; contributing to the welfare of others or making a contribution to family, faith community, or society at large; and gaining recognition for one’s accomplishments. Finally, adulthood can be defined in psychological terms, that is, by the level of maturity exhibited by a person. Mature persons are able to take responsibility, make logical decisions, appreciate the position of others, control emotional outbursts, and accept social roles. What it means to be an “adult” is a combination of many factors, the most important of which you will be introduced to in these pages.

Needs: Respect, Identity, and Intimacy

Adult development is not marked by definitive physical and psychomotor changes such as those seen in toddlers (e.g., learning how to walk), but it is full of challenging and largely unpredictable experiences. Adult life is marked by concepts such as independent life choices, midlife physical and emotional challenges and changes, generativity, facing the empty nest, the return of adult children, and the expansion of generations through the addition of grandchildren, although not every adult has these experiences. We would be better able to predict the response of a 5-year-old to a major illness than we would that of a 30-year-old. In addition, there may be differences in the way adulthood is experienced by men and women. Also, the specific point in history that a person enters adulthood may have profound implications for adult life. For example, many women who entered adulthood during the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s had more opportunities regarding work and sexual freedom than the previous generation of women. Finally, development may also differ because of sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and education, to name a few differences.

Biological Development during the Adult Years

From adolescence on, human beings continue to grow and mature. Aging can be defined as “the sum of all the changes that normally occur in an organism with the passage of time.”3 Demographers, social scientists, and developmental psychologists consider young adulthood to be roughly between ages of 21 and 40 and middle adulthood to be between the ages of 40 and 65.4 Aging, like adulthood itself, is complex and varies from one person to another. The rate at which individuals age is highly variable, but so is the way they adapt to age-related changes and illness. Aging also gives rise to feelings of anxiety in a way no other area of human development does. Failing intellectual or biological functions in the middle years can become a preoccupation for your patient. For example, during this period the pure joy of physical activity experienced in younger years may acquire a sober edge. One of us overheard a man who for years has enjoyed running just for the sport of it tell his friend, “Yeah, my running will probably guarantee that I live 5 years longer, but I will have spent that 5 years running!”

Adults may also worry about the age-related changes that begin to take place in their body structures and functions. Suddenly, forgetfulness is no longer something to be taken lightly but could portend more serious problems generally associated with age. Perhaps the anxiety that aging provokes is due to the close relationship most of us believe exists between biological development and illness, decline, and death.5 Rather than view aging in this way, gerontologists have proposed the concept of compressed morbidity, which suggests that people may live longer, healthier lives and have shorter periods of disability at the end of their lives. The focus of health care then becomes one of prevention, health improvement for chronic disease, and postponement of disability or death rather than cure.6 In Chapter 17 we will discuss different views of aging and their impact on your interactions with older patients

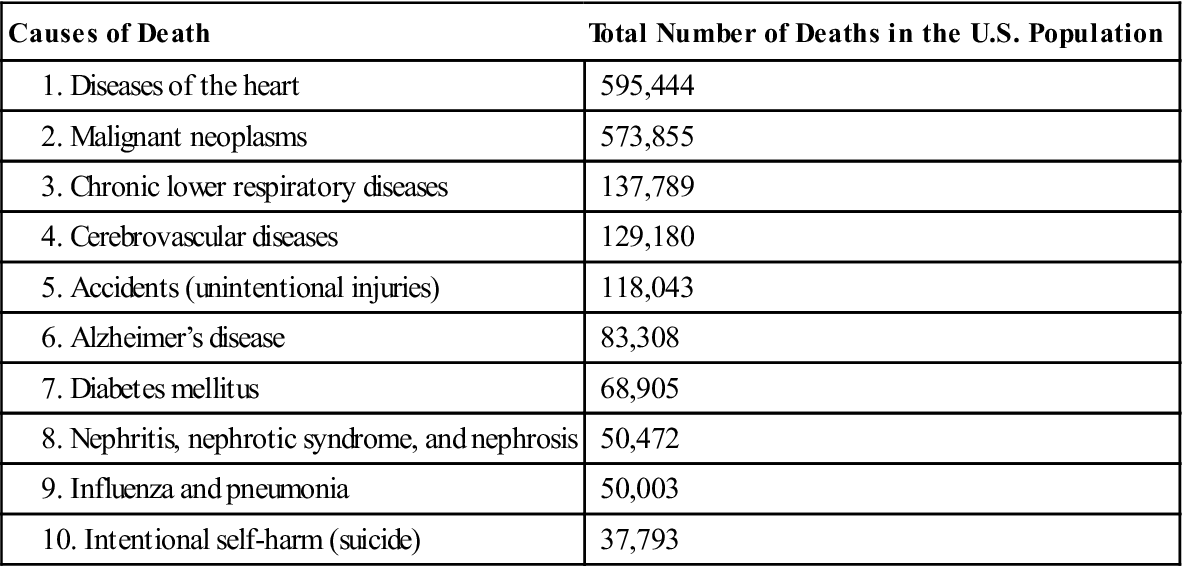

In human beings the lifespan is thought to be about 110 to 120 years. In Western nations the average life expectancy is said to be 78.7 years, although this varies according to race and other variables (Black females, 78 years; Black males, 71.8 years; White females, 81.3 years; and White males, 76.5).7 The 10 leading causes of death for all age groups in the US are listed in Table 16-1.7 Cause of death varies according to race and sex, but this table provides a general idea of the types of illnesses you will encounter most often with adult patients. You will note that many of these causes of death are chronic diseases. Chronic disease is a major health problem in the United States. One in four Americans has multiple (two plus) chronic diseases, and the burden of chronic disease among racial and ethnic minorities is notably disproportionate.8 Conditions such as diabetes, depression, and cardiovascular disease are now being diagnosed and treated earlier in adulthood than ever before.

TABLE 16-1

| Causes of Death | Total Number of Deaths in the U.S. Population |

| 595,444 | |

| 573,855 | |

| 137,789 | |

| 129,180 | |

| 118,043 | |

| 83,308 | |

| 68,905 | |

| 50,472 | |

| 50,003 | |

| 37,793 |

From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics Report January 11, 2012: Deaths: preliminary data for 2010, Natl Vital Stat Rep 6(4):1–69. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr60/nvsr60_04.pdf.

As science progresses we learn more about how individual genes, biology, and behaviors interact with the social, cultural, and physical environment to influence health outcomes. Targeting prevention, illness management, and lifestyle modification in young and middle adulthood can increase quality of life and prevent the development and severity of chronic disease in older adulthood. Young adulthood is often referred to as the healthy years and the hidden hazards. Individuals in early and middle adulthood tend to underestimate the impact that poor lifestyle choices may have on their overall health span.

Early Adulthood

As discussed in Chapter 15, it is during late adolescence that self-identity begins to form. These processes of identity exploration and consolidation continue in the beginning of early adulthood (generally between the ages of 17 and 24). Adulthood is not defined by a single factor, rather an integration of cognitive development, physical development, and societal experience. How individual’s transition through adulthood is heavily influenced by experiences in previous stages of life.

In the span of a few generations, the path to adulthood has changed dramatically. Today’s young people are taking longer to leave home, attain economic independence, marry, and form families than did their peers half a century ago.9 These longer transitions put strains on families and institutions (such as health care systems) that work with young adults. For example, adults who have children might believe that they have moved through an adult developmental task of parenting children, only to find their children returning home after a divorce or unemployment. Therefore, a parent or parents who might have been rejoicing in an empty nest and time for each other may find their adult children under their roof once again and with grandchildren in tow.

Thus, the societal context of delayed acquisition of independence, earlier physical maturation characteristic of modern cultures, pressures on young people to grow up fast, return of adult children to their parents’ home, and delayed childbearing all complicate the traditional views held about progression through adulthood.

Even if we hold several variables constant (e.g., age, gender), it is still difficult to predict how two adult patients would react to the same diagnosis. Consider the example of Ms. McLean and Ms. Jeon, both of whom have just learned that they have in situ cancer of the cervix.

Both of these women’s feelings and reactions are the result of their life experiences to this point, which in turn, are determined by their roles and familial contexts. In Ms. McLean’s case, her response to the diagnosis is influenced by her roles as daughter, sister, niece, fiancée, and psychologist. Mrs. Jeon’s response is influenced by her roles as mother, wife, daughter, granddaughter, and receptionist. These life roles are only a few that we can ascertain on the basis of the information presented in the brief cases. It is highly probable that both women have many more roles. Ms. McLean planned her life around finishing her education. Mrs. Jeon’s has revolved largely around her family. In short, just looking at their ages, it would be impossible to predict how Ms. McLean and Mrs. Jeon would interpret this crisis.

Illness and injury invariably result in changes in the patient’s identity, as described more fully in Chapters 6 and 7. Identity provides continuity over time and across problems and changes that arise in life. So there is a sense of maintenance of self through identity and yet room for change to accommodate the vicissitudes of life. Adult patients are generally more capable of entering into a professional relationship as an equal partner than younger people. Even though adult patients are better able to protect their own interests and make their wishes known, they are still worthy of the respect that we accord to younger, generally more vulnerable, patients. Respect continues to be one of the hallmarks of effective interaction as we work our way through the lifespan.

Intimacy is another developmental task of the adult. According to Erikson, adult development is marked by the ability to experience open, supportive, and loving relationships with others without the fear of losing one’s own identity in the process of growing close to another.3 You were introduced to the difference between personal and intimate relationships in Chapter 5 illustrating that the type of intimacy a patient will experience with family members, lovers, and friends is deeper and more involving than personal caring relationships the patient and you will engage in. It is that deeper intimacy that Erikson is talking about. The major developmental facets of adult life are referred to repeatedly as we explore the social roles, meaning of work, and the challenges of midlife.

Psychosocial Development and Needs

Maturity requires the acceptance of responsibility and empathy for others. The concept of achievement central to adult life can be defined in a number of ways. Some midlife challenges discussed later in this chapter seem to stem from a person’s having adequately assumed responsibility and realized his or her achievement potential, whereas others arise when the individual has failed to do so.

A profile of a person in the adult years of life will necessarily involve a consideration of his or her sense of “responsibility.” When we ask if someone is willing to “assume responsibility,” we are concerned with acts that the person can do and has voluntarily agreed to do. Given these conditions of ability and agreement, we want to know whether the person can be trusted to carry out the acts, regardless of whether the agreement was explicit (i.e., a promise to abide by the terms of a contract) or implicit (i.e., a promise to provide for one’s own children or parents).

Underlying the idea of acting responsibly is an assumption that the individual is a free agent (i.e., one who is willing and able to act autonomously). Thus, a person coerced into performing an act is not considered to have accepted responsibility for it.

During adulthood, there is another aspect to acting responsibly: it involves having a high regard for the welfare of others. The adult must find a way to support the next generation by redirecting attention from him or herself to others. In other words, the adult learns to care.10 This involves empathy for the predicaments that befall others in life. The acts may flow from a free will, but the will must operate in accordance with reasonable claims and justifiable expectations of other people. The claims of society on a person peak during the middle years, so “acting responsibly” must be interpreted in terms of how completely the person fulfills the conditions of those claims.

For instance, in Hindu culture, one stage of acting out one’s karma involves active engagement in the affairs of family and business. Only when an individual has successfully completed these tasks may he or she move on to higher, more contemplative levels of existence.

One way to view the matter in our culture is to review the discussion of self-respect in Chapters 4 and 5. Although our discussion there was on you, the same principles apply to adult patients. This basic value is among the most essential ingredients of “the good life.” During the adult years, most people perceive their self-respect as being vulnerable to the judgments of others: One’s self-respect at least partially depends on the extent to which he or she commands the respect of employer, family, and friends. This idea is related to our concept of “reputation”: One commands respect by giving due consideration to society’s claims. Hiltner notes, correctly we believe, that, to a large extent, even the personal values of the middle years must include a regard for others. For most, it is a highly social period when interdependencies are complex and pervasive.11

Adulthood sometimes involves people going back to previous developmental tasks such as establishing an identity if they did not resolve these issues previously in late adolescence or early adulthood. For example, in a study of gay males in middle adulthood, the researcher found that “these men were facing issues befitting their chronological age (nongay issues that had been worked on while leading a double life), as well as unresolved identity issues from the past.”12 The key point of this study is that the subjects were initially working through the earlier stage of development rather than reworking earlier developmental issues that can occur throughout adult development.

Social Roles in Adulthood

Several social roles most fully characterize this period involving primary relationships, parenting, care of older family members, and involvement in the community in the form of political, religious, or other social or service organizations and groups.

Primary Relationships

It is almost always during adulthood that a person decides with whom lasting relationships will be developed. Fortunately, an increasing number of older people are also developing new relationships, but they are usually people who were able to sustain deep and lasting relationships in the middle years as well.

The primary relationship takes priority over all others, the most common type being the relationship with a spouse. Choosing a spouse or other permanent companion and becoming better acquainted (i.e., learning to know the person, discovering potentials and limits, similarities and differences, and compatibilities and incompatibilities) are processes interwoven with the more basic activities of eating, sleeping, acquiring possessions, working, worshipping, relaxing, and playing together.

Those who do not enter into a marriage relationship sometimes develop a deep and lasting involvement with a partner, often a friend or sibling. One of your first tasks of respectful interaction with an adult patient is to find out if there is a key person in his or her life and, if so, who that person is. This can be accomplished without unnecessary probing into the person’s private life. Particularly in times of crisis the patient looks to that key person for comfort, sustenance, and guidance. However, sometimes the person you assume would be the most supportive is not. Consider the case of Mary Ogden and Pam Carlisle.