Respectful Interaction when the Patient Is Dying

The newspaper near his chair has a photo of a Boston baseball player who is smiling after pitching a shutout. Of all the diseases, I think to myself, Morrie gets one named after an athlete.

You remember Lou Gehrig, I ask?

“I remember him in the stadium, saying good-bye.”

So you remember the famous line.

“Which one?”

Come on. Lou Gehrig. “Pride of the Yankees?” The speech that echoes over the loudspeakers?

“Remind me,” Morrie says. “Do the speech.”

Through the open window I hear the sound of a garbage truck. Although it is hot, Morrie is wearing long sleeves, with a blanket over his legs, his skin pale. The disease owns him.

I raise my voice and do the Gehrig imitation, where the words bounce off the stadium walls: “Too-dayyy . . . I feeel like . . . the luckiest maaaan . . . on the face of the earth. . . .”

Morrie closes his eyes and nods slowly.

“Yeah. Well. I didn’t say that.”

—M. Albom1

Chapter Objectives

• Discuss the dying-death relationship and some sources of understanding about dying and death

• Discuss denial in regard to its effects on respectful interaction

• Explain several areas of consideration in setting treatment priorities when a patient is dying

This excerpt, from a book titled Tuesdays with Morrie, chronicles the last months of a man’s dying as it is recorded through the pen of his friend and former student. Here you catch them in one of their many exchanges, the young man trying to make conversation and the dying one bringing the narrative back to the heart of the matter—his own unique experience of dying. Of all the challenges you will face, your work with people who are dying will provide some of the greatest opportunities to use your skills in the health care environment.

Terminally ill is a term that is commonly seen in the literature to describe people who are dying. Like all labels, it allows people in this group to be identified easily according to their special needs. At the same time, we refrain from using it in this chapter. One difficulty with the term is its generality. Persons such as Morrie, who suffered from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease), may live for many months or years. Another person with a different condition may die within days or weeks. Still, both are labeled terminally ill.

Many health professionals, as well as others, tend to place people on the “critical list.” One of the authors remembers a friend who had lived for more than 10 years with a diagnosis of malignant lymphoma. He went into the hospital for his periodic blood test. A health professional who had come back to work after a 5-year hiatus greeted him cheerfully, “Are you still around?”

She was apparently astonished that this “terminally ill” patient had not died long ago! The patient recalled that although he knew her intentions were good, her greeting led to the most severe depression of his entire illness. As with all types of patients, the key is to look for the distinguishing factors that make this person’s situation unique and respond respectfully to the needs that arise out of that individual person’s experience. Toward achieving that goal, a first step toward any health professional’s understanding of a patient’s situation is to gain some general idea of how the dying process and death are viewed within the larger society.

Dying and Death in Contemporary Society

Dying is first and foremost a personal experience. All persons share some awareness that the end of the dying process is the death event. What does this mean to a person? In the minds of some patients or their families, a known diagnosis and somewhat predictable range of symptoms make them feel robbed of the “natural” flow of life. The dying process feels unnatural, an imposition.

A life-threatening condition generates new fears and concerns. Fortunately, for others it is also an opportunity to conduct long-neglected business, put one’s affairs in order, or pursue a postponed adventure. Anticipation of the death event, too, creates its own concerns, fears, and hopes. For most people death remains perhaps the ultimate mystery.

Dying as a Process

How do we gain an understanding of the relationship of the process of dying to the end point of death?

In almost all cultures, stories passed down from childhood onward in fairy tales or, in some cultures, the mythic stories deeply inform our understanding from childhood—or lack of it. Note how in the following popular Western fairy tales death is something that happens to the bad guys, and a notable goal is to help bring it about:

Down climbed Jack as fast as he could, and down climbed the giant after him, but he couldn’t catch him. Jack reached the bottom first and shouted out to his mother, who was at the cottage door. “Mother! Mother! Bring me an axe! Make haste, Mother!” For he knew there was not a moment to spare. However, he was just in time. Jack seized the hatchet and chopped through the beanstalk close to the root; the giant fell headlong into the garden and was killed on the spot.

So all ended well. . . .2

Then Grethel gave her a push, so that she fell right in, and then shutting the iron door she bolted it. Oh how horribly she howled! But Grethel ran away, and left the ungodly witch to burn to ashes.

Now she ran to Hansel, and opening his door, called out, “Hansel, we are saved; the old witch is dead!”3

Many Western childhood portrayals show no connection between the process of dying and the final death event. Both the health professional and patient may share beliefs about the “unnaturalness” of death rooted in many Western childhood stories. Of course, not all cultures have the same understanding of life and death. How might your relationship with a patient be different if, say, he or she grew up with the deep memory of this childhood story recounted by Mitch Albom, the author of Tuesdays with Morrie (whose conversations with his dying friend led him to read about how different cultures view death)?

There is a tribe in the North American Arctic, for example, who believe that all things on earth have a soul that exists in a miniature form of the body that holds it—so that a deer has a tiny deer inside it, and a man has a tiny man inside him. When the large being dies, that tiny form lives on. It can slide into something being born nearby, or it can go to a temporary resting place in the sky, in the belly of a great feminine spirit, where it waits until the moon can send it back to earth.

Sometimes, they say, the moon is so busy with the new soul of the world that it disappears from the sky. That is why we have moonless nights. But in the end, the moon always returns. As do we all. . . .1

In today’s rich diversity of patients an essential step in creating a therapeutic relationship based on care is to try to gain some understanding of dying as a process to be viewed apart from death itself. This provides a starting place for further deliberation about how to respect what a patient or family says, how they behave, and what their attitudes are toward various aspects of their interaction with you and others during the dying process.

Denial

It is often said that Western societies are death denying. What can that possibly mean when all around us people are dying every day from illness, accidents, violence, old age, war, and other causes? Probably the best explanation is that although there is evidence everywhere of our mortality, we do our best to hold the inevitable at arm’s length.

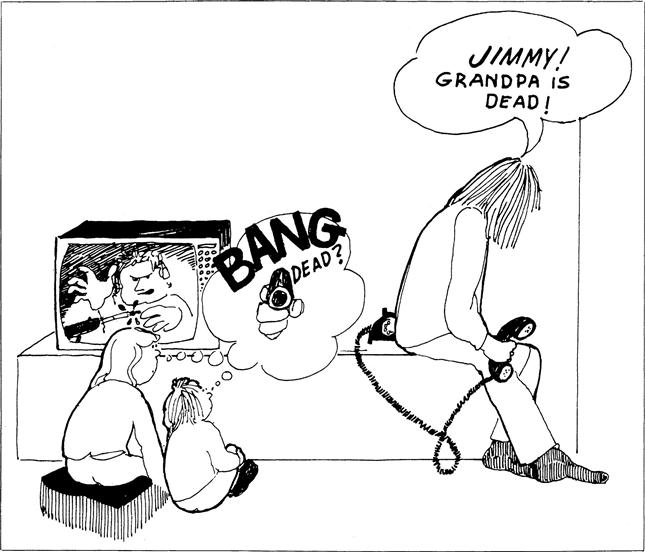

In many parts of Western culture, treatment of the dead body is one expression of a need to deny death its power. The dead body is painted and dressed to make it appear alive, although a sign of life, such as a sigh or fluttering eyelash, would cause most people to rush screaming from the room. For the most part, however, denial has simply become more subtle. For example, a subtle denial that death is the end point of the dying process is manifested in the incredible scenes of violence and killing viewed in films and on television, as Figure 12-1 illustrates. People of all ages see the culprit killed, but the same actor appears on next week’s show, having adventures in dangerous places. Another response is a distancing that keeps death at arm’s length for as long as possible even during one’s dying process. This attempt to stave off the inevitable is also experienced by loved ones and poignantly is conveyed in the following quote of a 51-year-old woman who learned that her best friend was dying of cancer:

Before one enters this spectrum of sorrow, which changes even the color of trees, there is a blind and daringly wrong assumption that probably allows us to blunder through the days. There is a way one thinks that the show will never end—or the loss, when it comes, will be toward the end of the road, not in its middle . . . I meant that I might somehow sidestep the cruelty of an intolerable loss, one rendered without the willful or natural exit signs of drug overdose, suicide, or old age.4

At the same time, the health care team can be helpful in assisting both patients and loved ones not to become stuck in prolonged denial such as happened in the following:

My husband, John, age 55, was handed his diagnosis of liver cancer by a newly graduated doctor—John’s own had just retired. “As I’m sure you know,” the young man had blushingly begun, and John said simply, “Yes.” We walked out of the office holding hands and cold to the marrow.

Near the end, I started looking for signs that the inevitable would not be inevitable. I watched a few leaves that refused to give up their green to the season. I took comfort in the way the sun shone brightly on a day they predicted rain—not a cloud in the sky! I even tried to formulate messages of hope in arrangements of coins on the dresser top—look how they had landed all heads up . . . what were the odds? I prayed, too, in a way that agnostics do at such times. Sorry I doubted you “dear God, help us now.” I stood shivering on our back patio in the early morning with my mug of coffee and told whatever might help us that now would be the time . . . but my dreams betrayed me: John, shrunk to the size of a thumb, fell from my purse where I’d been carrying him and was stepped on. In another dream, I took a walk around the block and when I came back, my house was gone.5

Denial mechanisms are so widespread in almost all Western societies that we gave special attention to it, but obviously there are other considerations and responses that we turn your attention to now.

Responses to Dying and Death

Because nearly all of us dread the thought of gradual and certain loss, the news of a life-threatening diagnosis is almost always disquieting. In this section you have an opportunity to think about what this state of affairs gives rise to.

Common Stresses and Challenges Demanding Response

What would be your biggest challenges if you learned that you were dying? Most people can vaguely imagine and project what they would dread most; once the diagnosis is made, however, the reality of their specific situation intrudes. Then a patient’s previous notions about a particular disease or injury and the known experiences of others who have had it combine to create a vivid picture of what the patient believes to be ahead. The following are some of the most commonly expressed concerns.

Anticipation of Future Isolation

As you learned in studying Chapter 6, separation from the routine and regularity of life has a profound disorienting effect on many people. Often a prolonged dying process involves gradual loss of habits, acceptance by others, and familial, social, and societal roles.

The fear of separation from the familiarity of home and routine as a way of ordering one’s life becomes a reality for many. At the heart for most is a deeper fear of abandonment by loved ones and caregivers. Anxiety about this may be expressed in comments such as: “They are starting to ignore me”; “My family is busy with other things”; “The nurses skipped my medication this morning, so they are probably giving up on me”; and “They spend more time with the woman in the next bed, but of course they know I’m dying.” Many persons are aware of the practice of being admitted to the hospital to die or of having to spend the final period of their lives in a care facility, and some contribute to their isolation by rejecting visitors or others who come to visit, fearing that visitors have come to “hang the crepe,” an expression referring to an old custom of hanging a lightweight fabric above their doorway as a sign of mourning, or worse.

You can “treat” (allay) the patient’s fears of isolation by your own presence. You cannot always ensure patients that their loved ones will not “jump ship” when the going gets rough, because sometimes families or friends do. Observing this tapering off of supportive relationships is often trying for you, let alone the patient. Relationships are bound to be altered during this time; some friends and relatives disappear because of indifference, despair, or exhaustion, and those who do not become more cherished. Health professionals are often eventually able to ascertain who, among the many at the onset, will endure. Often, it is wise to begin providing your own support to those whom you judge to be the most enduring so that the patient will continue to have a community of support as the condition progresses.

Prospect of Pain

Those who have known others who experienced a distressful end to life cannot be sure that their own dying will not be equally painful or worse. Fortunately, modern modes of health care intervention for pain today have the potential to nearly obliterate the physical pain of dying, though it is still a challenge in some settings to get positive pain relief.6 Anxiety and depression can have a heightened effect on pain, whereas distraction and feelings of security tend to diminish the suffering associated with pain. These patterns of response, first characterized by Kubler-Ross several decades ago, have since been shown to better being understood as the range of responses that come and go from time to time.7 Therefore the patient’s suffering may be decreased by your reassurance, presence, compassion, and caring discussed in Chapter 10 and elsewhere.

Resistance to Becoming Dependent

Real or feared loss of independence during illness or injury is often a challenge, as also described in previous chapters. Continued independence within whatever sphere of decision-making a person can exercise when in the dying process usually remains a high priority. Proof that they have thought about this is shown in their expressions of astonishment at having reached a point in their symptoms they had previously believed would be totally unbearable. Indeed, everyone has ideas beforehand of what he or she believes to be the “outer limits” of what one could bear: loss of bowel and bladder control; sexual impotence; inability to feed oneself, to communicate verbally, or to think straight; unconsciousness; or other loss. Often (though not always) patients’ acceptance changes after a period of fighting the specific loss.

Patients’ experiences of real or imagined isolation, pain, and increasing dependence are basic, but there are other concerns as well, such as the dread of suffocation and the fear that one’s loved ones will not be adequately provided for. A person who dies suddenly in a car accident or plane crash or from a myocardial infarction may have long harbored these fears but did not have a period of prolonged illness during which these concerns surfaced. For instance, a man who has had trouble openly expressing affection to his wife may be able to do so by sharing his sorrow that he fears she will not be adequately provided for. An indirect means of communication, such as writing a letter or telling a friend how wonderful she is, serves a similar purpose. You can be instrumental in making suggestions to help such a patient carry out his or her wishes if you get a hint that the patient desires to do so.

In summary, during their dying process, people must rely on their own best inner resources and the support of family, friends, and health professionals to sustain them as they face their challenges. Any hesitance, embarrassment, or disdain you show when a person expresses a concern, even one that seems unfounded to you, will exacerbate the suffering associated with it.

Reckoning with What Death Might Mean

Different cultures and individuals treat the moment of transition from alive to dead differently, but for many it is not something to relish. What is the range of expressions about what will happen when death comes?

Many people believe that after this life there is something else. The varieties of religious or philosophical beliefs are many, regarding the relationship of this life to the next.8 Predominant beliefs in many religions, especially but by no means only those associated with Eastern religions such as Hinduism, propose that “death” is a process of birth and rebirth (e.g., reincarnation). The last step is not extinction but perfection, at which time one is absorbed into a “place” or into a “being” where complete unity of all beings is realized. Depending on the religion, the type of being one will become after physical death and the opportunity for the final step into ultimate unity may or may not depend on the type of life one lived on earth during an embodied human lifetime. In Islam one may be transported through several levels of paradise depending on the type of life one has lived.

Some people believe in the resurrection of souls only, whereas others believe that the actual human body will be restored, usually in an improved form. There is one version of a literal, sudden bodily resurrection (sometimes referred to as the “rapture”) in which those—both dead and still living—who have lived holy lives will be immediately transported to heaven, whereas others will be left behind forever to suffer the consequences of their sins. Other Christians have different versions of what it means to be “resurrected,” although all share this basic belief.

You will meet individuals who talk with anticipation about “going to meet the Lord,” whereas others are sure their lives will not meet the standards of acceptability and they will be consigned to suffering of some kind. Knowing that any of these beliefs about immortality may influence the way an individual interprets the impact and meaning of his or her own impending death, you can be better prepared for comments from the patients or for rituals a patient and family engage in during the dying process.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree