Respectful Interaction in Difficult Situations

She asks for help and I have given it to her. She has been on various medications but nothing seems to work. She is a sad case really, and her anxiety seems to stem from a poor home environment. She gets anxious and then gets anxious about being anxious. I prescribe, but I know she will be back again in a short time. It would not be so bad if she tried to help herself.

I. Shaw1

Chapter Objectives

Many health professionals view working with dying patients and their families as one of the greatest challenges they face in health care. However, as you read in Chapter 12, working with patients who are dying can sometimes be full of joy and sorrow. Even though you might experience loss and grief when a patient you have cared for dies, there is often also an accompanying sense of satisfaction that you were able to make his or her death a little easier, a little less painful, or less lonely. There are other patient care situations in which you will not come away with a sense of satisfaction, but one of profound frustration. This chapter focuses on difficulties inherent in the health professional and patient interaction that have not specifically been addressed elsewhere in this book or that bear reemphasizing. We suggest that you refer to Chapters 10 and 11 to review the content on establishing relatedness, recognizing boundaries, and creating professional closeness. You will need to use all of these insights and skills in your work with patients who challenge your conceptions of what it means to be a “good” health professional. Moreover, you will have an opportunity to think about other factors that can create great tension in the health professional and patient interaction, such as disparities in power and role expectations or an unsafe working environment that can cause harm to the health professional or patient. We devote this chapter to some summary statements about how to work more effectively with “difficult” patients and offer ways to effect change in “difficult” settings and situations.

Sources of Difficulties

Generally, when you enter a relationship with a patient, you have good reason to expect that things will go well, or if there are problems, you expect that they can be resolved. However, there are situations in which even your best efforts cannot make things right. When this happens, a common response is to look for a place to lay the blame. For example, you might wonder what else you could have done for the patient, or you might reason that the patient was not ready for treatment, or you may become defensive and decide that the patient was disruptive, noncompliant, maladjusted, or any number of other negative labels. Refer to the quote that opened the chapter regarding a patient who does not seem to be meeting the health professional’s expectations for improvement. Especially note the last sentence indicating that the patient is at least partly to blame for the situation. Difficulty relating to a patient may originate in the health professional, in the interaction itself, or within the setting in which the interaction takes place.

Sources within the Health Professional

As emphasized throughout this book, you bring a wealth of experiences, education, prejudices, and values to your interaction with patients and their families. All of these factors can affect how you react to a particular patient. For example, recall the discussion on transference and countertransference in Chapter 10. A patient may remind you of your third-grade teacher whom you particularly feared and disliked. This past experience can arouse intense emotional reactions in the present relationship. In addition, your personality and how you deal with stress will play a large part in how you manage patient care situations that are interpersonally difficult.2 In fact, your personality, more than your professional or demographic background, may explain why you react negatively to some patients and certain situations and have little difficulty with others.

For the health professional, the most reliable indicator of a negative emotional response is an unfavorable gut response or sense of discomfort in encounters with a particular patient.3 If you are attuned to monitoring your feelings, then you can try to assess how much anger, fear, or guilt you bring to the interaction and try to manage those feelings before trying to manage the patient. After you identify the emotions you are experiencing, two questions often follow: “Why is this happening?” and “Where is this emotion coming from?”

Although it is a widely held belief, which has certainly been emphasized in this book, that health professionals should be nonjudgmental in their relationships with patients, it is a fact that we often find some patients more likable than others. More than 50 years ago, Highley and Norris4 asked their nursing students to identify major “dislikes” related to working with patients. The types of patients the students said they disliked in 1957 can still be found in the clinical practice literature today. The students reported the following dislikes:

1. Patients who feel bad and complain after everything has been done for them

4. Patients who are extremely demanding

5. Patients who can help themselves but insist on the health professional doing everything

The common denominator in these dislikes is that either the patients made the students feel guilty because of their dislike for the patients or, because they were never satisfied, the patients made the students feel inadequate as nurses. In general, patients who do not affirm the health professional’s identity (i.e., accept and appreciate professional assistance) are considered bad patients. The patient’s rejection of the health professional’s help can easily be misread as rejection of the health professional. This rejection can take many forms, ranging from complaints to incessant demands, manipulative behavior, ingratitude, or basic noncompliance with advice or treatment.

Because this study was conducted in the 1950s, the students might not have mentioned some problems people are more self-consciously aware of today, such as patients who make sexually explicit remarks that cause embarrassment or aggressive patients who frighten or sometimes even threaten or physically harm health professionals.

These findings lead to another factor that is characteristic of health professionals and can cause difficulties in patient interactions: high expectations regarding the ability to help. As you progress through your program of study to become a health professional, the ideal is reinforced: You should be able to function effectively in all patient situations, and you are solely responsible for the success or failure of these interactions. This may not be what your teachers or we want to convey, but it is often what health professionals feel at the beginning of their careers. Thus, long before you have a full complement of skills with which to deal with difficult situations, you may blame yourself for failing to meet the needs of a challenging patient. Before jumping to self-blame for not meeting these unrealistic expectations, you need to recognize that many missteps occur before full competence is attained. Even then you should continue to work at establishing realistic expectations of yourself as a health professional.

Your perception of the patient’s socioeconomic status can also influence your reactions to a patient. You are encouraged to review the content of Chapter 3 regarding appreciating differences and recognizing discrimination. A perceived difference in socioeconomic status can have a profound effect on the health professional and patient interaction. Papper noted:

The very poor may be viewed as undesirable unrelated to their ability to pay. Even when the physician has genuine concern for the economically disadvantaged, he may because of his own background, unwittingly regard the extremely poor as different, with a flavor of inferiority included in the difference.5

Papper’s personal observation of his medical colleagues was substantiated in a research study by Larson, who presented nurses with case studies in which the patient was identified as middle or lower class, with a more or less serious and more or less socially acceptable illness. The specific findings of Larson’s study indicate that persons ranked as “lower class” regardless of other social variables were perceived as relatively passive, dependent, unintelligent, unmotivated, lazy, forgetful, noncomprehending, uninformed, inaccurate, unreliable, careless, and unsuccessful.6 We return to the findings related to socially unacceptable illness later in this chapter because this also leads to the labeling of a patient as difficult or undesirable.

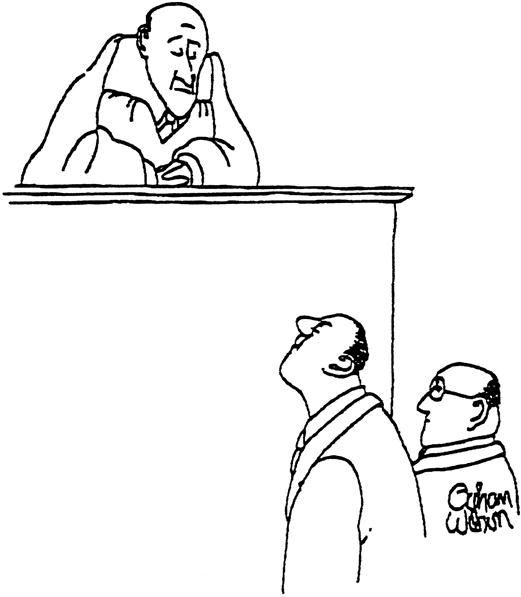

Socioeconomic differences between patient and health professional can surface in values about cleanliness. Most health professionals are from the middle or upper-middle class and hold certain values about cleanliness and other “correct” ways of being in the world. They are not only unfamiliar with the ways of poor people but may also hold them in disdain (Figure 13-1). Persons in lower socioeconomic groups may be so concerned about basic human needs, such as food and shelter, that they have little time or resources for luxuries such as bathing. It may appear that they do not care at all about cleanliness. Middle-class health professionals often, unconsciously, try to impose their values on patients concerning cleanliness. If neither the health professional nor the patient is aware of differences in socioeconomic status that generate values about bathing and hygiene, a struggle can ensue regarding cleanliness that is out of proportion to its importance in most patient care situations. Matters of hygiene are not the only issues that can escalate into battles with patients. Confrontation and power struggles should be avoided at all cost. Tactics for successful negotiation are outlined later in this chapter.

Sources within Interactions with Patients

What makes a patient “undesirable?” Patients who are overly demanding or who do not comply with treatment are generally labeled as problematic, as this family physician notes:

Let’s be blunt. It’s hard to care for difficult patients. It’s sometimes impossible to actually like them. This species of sick individuals tends to strain time, patience, and resources. They often generate a cascade of phone calls. They sometimes demand a heap of medically unnecessary tests. They occasionally refuse recommended treatment. Many have unreasonable expectations. Some whine and gripe incessantly. A few threaten to sue.7

Other types of behaviors that commonly elicit a negative response from health professionals are violence, anger, or self-harm behaviors such as substance abuse. Kelly and May8 proposed a theoretical framework for the way health professionals conceptualize good and bad patients using an interactionist perspective. According to this view, patients come to be regarded as good or bad not because of anything inherent about them or in their behavior but as a consequence of the interactions between health professionals and patients. Patients are not passive recipients of care but active agents in the interaction process. Kelly and May explain that patients have the power to “influence, shape and reject professionals’ attempts to impose a definition on their situation, with profound consequences for nurse-patient relations and the professional task.”8 Even though Kelly and May focused on the nurse-patient interaction, their framework appears applicable to all health professionals and their reaction to withholding affirmation for the health professionals’ roles.

As you can see from the list of dislikes that the students in Highley and Norris’s study generated, the focus of the dislike easily moved from dislike for the consequences of inappropriate or unacceptable behavior to dislike for the patient. For example, patients with illnesses that are socially unacceptable are often labeled as difficult even if their behavior is a model of compliance. People with addictive disorders such as alcoholism or drug abuse are often viewed as unacceptable or bad patients. Even if a health professional views alcoholism as a disease rather than a behavior a patient should be able to control, the patient who has a problem with alcohol is commonly rejected by most professional personnel.9 Patients who appear to be responsible in some way for their illness or injury, such as obese patients or smokers, are also labeled as less worthy of respect than patients who are “blameless” for their present health condition. All of these patients have one thing in common: Either because of the nature of their health problems or the way they respond to the health professionals involved in their care and treatment, they withhold the legitimation that makes health professionals feel good about who they are and what they do.

Thus, a large part of the label a patient receives depends on our role expectations of patients in general and of patients with specific characteristics. One of the most basic expectations of patients is compliance with agreed-upon treatment. Noncompliance is largely viewed in health care literature as a problem to be resolved. The problem is located in irrational patient beliefs that contradict scientific evidence or in patients’ lack of knowledge or understanding.10 Thus, we assume patients are not following medical advice because they do not understand or have some misconception that prevents them from understanding. Major efforts, then, are directed toward getting patients to understand so that they will comply. An alternative view of noncompliance implicates the social context of patients’ lives as follows, “Within this alternative social view, it cannot be assumed that noncompliance is simply a matter of patients choosing not to follow advice. Instead, it is recognized that choice may be severely constrained by the social circumstances in which patients live their lives.”10

If health professionals approach the problem of noncompliance by trying to understand the factors in patients’ lives that mediate their cooperation, then efforts can be made to change those factors that are amenable to change or adjust treatment to meet the reality of a patient’s life.

Sources in the Environment

As we noted specifically in Chapters 8 and 9, the health professional and patient interaction takes place in a particular context. At times the context can be the source of difficulty in an interaction. For example, if the environment is strange and frightening, the patient or health professional may react in a fearful or angry manner. For many patients, a health care facility can be an extremely threatening place. Taken in this context, even a simple activity such as bathing can be viewed as menacing. Rader noted that for a person with apraxia (inability to execute purposeful, learned motor acts despite the physical ability and willingness to do so), agnosia (inability to recognize a tactile or visible stimulus despite being able to recognize the elemental sensation), and aphasia (loss of language function either in comprehension or expression of words)—symptoms often found in patients who have had a cerebrovascular accident—the standard nursing home bathing experience may be perceived as horrific. Consider these limitations, and place yourself in the patient’s position.

A person the resident does not recognize comes into her room, wakens her, says something she does not understand, drags her out of bed, and takes off her clothes. Then the resident is moved down a public corridor on something that resembles a toilet seat, covered only with a thin sheet so that her private parts are exposed to the breeze. Calls for help are ignored or greeted with, “Good morning.” Then she is taken to a strange, cold room that looks like a car wash, the sheet is ripped off, and she is sprayed in the face with cold and then scalding water. Continued calls for help go unheeded. Her most private parts are touched by a stranger. In another context this would be assault.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree