Respectful Communication in an Information Age

After surgery last May, my first memory upon awakening in the ICU was a feeling as if I were choking on the ventilator, and of desperately wanting someone to help me. I could hear the nurse behind the curtain. I lifted my hand to summon her, only to realize I was in restraints, immobilized. I felt as if I were being buried alive. Lacking an alternative, I decided to kick my legs until someone came. This worked. The nurse came and suctioned me briefly, then disappeared behind the curtain. Still afraid and still feeling as if I needed more suctioning and the presence of another near me, I kicked again. She returned, this time to lecture me on how I mustn’t kick my legs.

And then she left.

—S.G. Jaquette1

Chapter Objectives

• Compare and contrast models of communication

• Describe basic differences between one-to-one and group communication

• Identify four important factors in achieving successful verbal communication

• Assess three problems that can arise from miscommunication

• Discuss two voice qualities that influence the meaning of spoken words

• Identify two types of nonverbal communication, and describe the importance of each

• Describe how attitudes and emotions such as fear, grief, or humor affect communication

• Give some examples of ways in which time and space awareness differ from culture to culture

• Discuss ways to show respect through effective distance communication

Talking Together

Patients rely on verbal communication to try to explain what is wrong or seek comfort or encouragement from health professionals. Yet they may have difficulty with the language itself, with finding the right words, or they may literally be unable to speak and have to resort to gestures, such as the patient in the opening scenario of this chapter. Unable to use words to convey her needs, she spoke the only way she could—she kicked her legs.

The greater responsibility for respectful communication between you and a patient lies with you, although both must assume responsibility. By examining interdependent components of effective communication, you will gain insight into this critical area of human interaction. Health professionals rely on verbal, nonverbal, written, and electronic forms of communication to share information, plan care, and collaborate with others on the health care team.

In your work as a health professional you will be required to communicate verbally with a patient to (1) establish rapport, (2) obtain information concerning his or her condition and progress, (3) confirm understanding (your own and the person with whom you are communicating), (4) relay pertinent information to other health professionals and support personnel, and (5) educate the patient and his or her family. Periodically, you are expected to offer encouragement and support, give rewards as incentives for further effort, convey bad news, report technical data to a patient or colleague, interpret information, and act as consultant. Naturally, you will be more comfortable with some activities than with others, according to your own specific abilities and experiences. Nevertheless, all health professionals should be prepared to perform the entire gamut of communication activities.

Verbal communication is instrumental in creating better understanding between you and a patient. However, this is not always the result. You will often be able to trace the cause of a misunderstanding to something you said; it was probably the wrong thing to say, or it was said in the wrong way or at the wrong time. The way words travel back and forth between individuals has been the subject of a great deal of study in the communication field. Several models have been proposed to graphically describe what happens when two people exchange the simplest of words.

Models of Communication

Although the following quotation focuses on the exchange of information between the physician and patient, the same can be said of all health professionals as they communicate with patients. As you read the quote, recall the differences between how a patient tells his or her story that was elaborated in Chapter 8 and the traditional model of questioning to arrive at a diagnosis described here.

It is revealing to examine how this flow back and forth between physician and patient is shaped, what is revealed or requested, when, by whom, at whose request or command, and whether there is reciprocal revelation of reasons, doubts, and anxieties. When we look at the medical context, instead of a free exchange of speech acts we find a highly structured discourse situation in which the physician is very much in control. Some patients perceive this sharply. Others more vaguely sense time constraints and a sequence structured by physician questions and terminated by signals of closure, such as writing prescriptions.2

Communication understood in this way involves the transfer of information from the patient to the health professional so that a diagnosis or plan for treatment can be made. The focus is on the “facts” and generally begins with a question about what brought the patient to the health professional. However, once the initial complaint is stated, there appears to be little time or attention devoted to other patient-centered concerns.3

Think of some reasons this is problematic. For example, the first complaint that a patient mentions may not be the most significant. More important, the patient may take a health professional’s hurried rush through a discussion as an overt sign of disinterest and disrespect. Most interactions with patients take the form of “interviews” rather than a conversation or dialogue. Health profession students take great pains to learn this interview technique designed to reveal, by the process of data gathering and elimination, the patient’s health problem. The interview becomes a means to an end, the end being a diagnosis, problem identification, and treatment plan. As was noted in Chapter 8, this end may not be the one the patient is seeking. Furthermore, by strictly following the interview model of communication, the health professional effectively controls the introduction and progression of topics. This pattern of communication involves the use of power and authority but remains largely hidden from awareness. Patients may literally be unable to get a word in edgewise during the time they have to speak with health professionals.

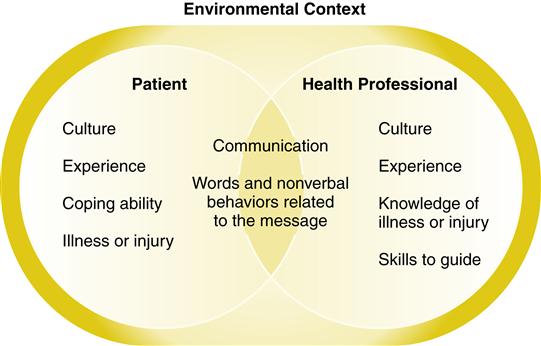

Imagine yourself changing your view of communication to one of a dialogue or conversation so that you can focus your attention on different aspects of the process such as minimizing the disparities in power and creating opportunities for true understanding between you and the patient. Even including questions and prompts like, “Tell me more about that,” or “What have you tried that helps?” offers greater opportunity for communication than mere “yes” and “no” types of questions. Also, keeping quiet and letting a patient tell his or her story is especially effective to build trust and gain a sense of what is most important to the patient. Figure 9-1 conceptualizes communication, both verbal and nonverbal, as the bridge between you and a patient. The model also includes some of the primary and secondary cultural characteristics introduced in Chapter 3 that influence what each party brings to the dialogue. All of these factors (and others not listed in the figure) have an impact on the interaction.

The Context of Communication

Figure 9-1 places the two parties who are communicating within an environmental context. Where, with whom, and under what circumstances the dialogue or conversation takes place can have a profound influence on the process and outcomes of the interaction. Clinical encounters between you and your patients are, according to Arthur Frank, a particular form of dialogue: “Most of the particularities generate tensions: stakes are often high for both parties, time is often limited, intimate matters are being broached between comparative strangers, power differentials intrude, and—not last but enough—both parties often have idealized expectations for what should take place.”4

Thus, the internal context of this exchange between you and the patient sets it apart from everyday conversations. The external environment also has an impact on the process and outcome of your dialogue. Because of technology, you may find yourself communicating with the same patient in a variety of contexts (e.g., face-to-face in a clinical setting, talking on the telephone, corresponding via e-mail).

Face-to-Face or Distant

If someone is standing or sitting right in front of you, the type of interaction is different from what occurs on the telephone or through an e-mail message, text, discussion board, or chat room. What varies most between face-to-face interactions and those that occur across distances is proximity and the degree of relative anonymity. When we are in direct personal contact with another person, there are fewer places to hide our fears and discomforts. In fact, knowing this, some health professionals specifically choose areas of practice in which they will have little direct contact with patients.

When you have the opportunity to meet face-to-face with a patient, all of the possible ways of communicating can be engaged. Each sense can be a source of information about the other. This explains, in part, why the exchange is that much richer and, to some, more frightening than those that take place from a distance.

We will discuss various forms of “distant” communication tools later in this chapter. During your career there is a good chance you will use all sorts of devices to communicate with patients. Perhaps at some time in the future, a holographic, computer-generated version of yourself and the patient will virtually “interact” with each other. Face-to-face interactions with health professionals will continue but will be more and more supplemented by other forms of communication technology (Figure 9-2).

For example, surveys show that patients want to be able to e-mail their clinicians to get test results and ask questions.5 Online communication with patients has many positive attributes such as the verbatim record of the transaction between patient and health professional. However, e-mail is not well suited to urgent problems nor does it contain the nonverbal components of communication that are crucial to understanding.

One-to-One or Group

Before you begin any type of interaction with a patient, you should make sure the patient knows who you are and what you do. This sounds so basic that it hardly seems worth mentioning. However, some health professionals are so focused on getting on with the diagnostic examination or asking questions that they forget the introductions. Of course this is not necessary if you are seeing a patient often. If you have met before, but there has been some time between your interactions, it does not hurt to reintroduce yourself and explain your role. In addition, always wear your name tag with your name and professional role clearly displayed.

If you are meeting a patient for the first time, be sure to use his or her full name. Do not presume to address a patient, unless the patient is a child, by his or her first name until the patient gives you explicit permission. Ask the patient how to pronounce his or her name if there is any doubt about the correct pronunciation. The 6-year-old niece of one of the authors was highly insulted when her pediatrician continually mispronounced her first name after being corrected. The child said, “How would she like it if I kept saying her name the wrong way?” So even children noticed a lapse in respect.

After you introduce yourself, tell the patient what you do in a few sentences. It is helpful to practice this explanation with a sympathetic audience such as relatives or friends who will tell you if you are being too technical or confusing. Having established this initial rapport, you can now devote your attention to the patient before you and vice versa. We will address matters such as facial expression, gestures, and touch later in this chapter. All of these nonverbal forms of communication may override verbal messages, and this is especially obvious in a face-to-face interaction.

Working with an individual patient is far different from working with a group of patients. You will have the opportunity to interact with groups of patients or patients and their families or friends in addition to individual patients. Thus, it is important to become knowledgeable about group functioning because much of what you plan for and deliver may be accomplished through a group process. To have a constructive effect in a group setting you must be familiar with how a group influences individual behavior and the forces that operate in any group. The groups you interact with as a health professional may be spontaneously formed for a short period of time, such as a group of diabetic patients currently on the unit who come together for instruction about their diet, or they may be groups that will interact for longer periods of time, such as a support or therapy group in a rehabilitation setting. You will also work with interdisciplinary groups or peer groups in clinical practice. We focus here on the behavior that occurs when any group interacts and how you can improve the functioning of a group process whether you are the facilitator or a group member.

Groups that remain together over a period of time appear to go through various stages of development, and the behaviors during each can help you understand group process. The first stage is one of orientation or “groping.” Members try to figure out what the purpose of the group is at this initial stage. If you are working with a group of patients, it is important to identify the specific goal of the group or what is to be accomplished in a specific time frame. When you are in the leadership or facilitator role, you can do a lot to increase the effectiveness and decrease the anxiety and confusion of the group by clearly providing structure. The second stage of group process for groups who continue to work together is the “griping” stage. Members of the group express, either openly or covertly, frustration and anger with the group process. This phenomenon seems to symbolize the group members’ struggles to maintain their own identity and still be part of the group process. Stage 3 is the “grouping” stage where members figure out how to work together for a common purpose. Finally in stage 4 the group moves to the “grinding” stage, where they cooperate and focus on the task at hand.

Of course, not all groups move through these stages in a straightforward manner. Group composition can change, disrupting the growth process. Also, in the frantic pace of contemporary health care, groups come and go quickly; therefore, many times, little cohesion can be achieved. In other words, you may find yourself constantly working in the “groping” stage of group development, with your role remaining one of providing guidance and structure.

Institution or Home

In Chapter 2 we discussed a variety of environments in which patients receive care today. Whatever the environment in which you encounter patients, for social, psychological, and financial reasons, there is a strong tendency to medicalize the setting. So even in settings such as a skilled nursing facility or the patient’s home, medical props and devices shape the atmosphere.

It is evident to health professionals who work in patients’ homes that they are viewed as guests, at best, or intrusive strangers, at worst. Home care places the health professional on the patient’s turf. Communication in the home care setting is shaped by that environment. Health professionals are more deferential, more attuned to asking before doing. Other health care environments, such as intensive care units or emergency departments, do not even pretend to be “homelike” or welcoming to patients. The sights, sounds, smells, and urgency of these high-tech environments have a profound impact on patients, particularly because this environment is often foreign and threatening. Consider this excerpt from a poem involving a mother who gets her first glimpse of her child in a critical care unit in a hospital.

INTENSIVE CARE

… I am called.

But nothing prepares me for what I see, my child

in her body of pain, hooked to machines. Grief

comes up like floodwater. Her body floats on a sea

of air that is her bed, a force field of sorrow

that pulls me to her side. I touch pain I know

I have never felt, move into a new land

of nightmare. She is so still. Only one hand

moves, fingers oscillate like water plants risking

the air. Machines line the desks,

the floor, the walls, confirm the deep pink

of her skin in rapidly ascending numbers. One eye blinks. . . .

—L.C. Getsi6

Sensitive communication depends on an appreciation of the effect of the environment on what transpires between you and the patient.

Choosing the Right Words

The success of verbal communication depends on several important factors: (1) the way material is presented (i.e., the vocabulary used, the clarity of voice, and organization; and (2) the tone and volume of the voice.

Vocabulary and Jargon

As we note in Chapter 8, the descriptive vocabulary of the health professional is a two-edged sword. A student must learn to offer precise, accurate descriptions and must be able to communicate to other professionals in that mode.

Technical language is one of the bonds shared by health professionals among themselves. In contrast, highly technical professional jargon is almost never appropriate in direct conversation with the patient. It cuts off communication with the patient. It is imperative that you learn to translate technical jargon into terms understandable to patients when discussing their condition or conversing with their families. Only in the rarest instances are patients schooled in the technical language of health care sufficiently to understand its jargon, even in today’s world of the Internet, television, podcasts, and other health care–related media resources. Even when the patient happens to be a health professional, it is important to use easily understandable language when talking about what is happening with him or her. Do not assume that the therapist or nurse who is your patient is conversant in all areas of health care. The safest approach in working with another health professional who is your patient is to take a cue from the patient and use only the technical language that he or she introduces.

Another common area for miscommunication is when the health professional and patient literally speak different languages. As was mentioned in Chapter 3, the world is often literally at our doorsteps because of the influx of a variety of refugees and immigrants into the United States. It is a rare health professional who does not routinely encounter language barriers with patients.

Numerous options exist for bridging these language barriers including interpreters, bilingual health professionals, and untrained volunteers. There are several reasons to avoid the use of family members and other untrained volunteers as medical interpreters such as:

![]() Interpreters close to the patient may not be able to disregard their views regarding the situation, which can bias the information that is shared.7

Interpreters close to the patient may not be able to disregard their views regarding the situation, which can bias the information that is shared.7

![]() Family interpreters, in particular, often speak as themselves rather than merely providing accurate information between parties.8

Family interpreters, in particular, often speak as themselves rather than merely providing accurate information between parties.8

![]() Untrained interpreters may be emotionally harmed because of the stress of performing an essential activity for which they are not prepared.9

Untrained interpreters may be emotionally harmed because of the stress of performing an essential activity for which they are not prepared.9

This is not to say that formally trained interpreters are the only or best recourse. Limited data indicate that the use of nonverbal supplementation to verbal communication can help lead to sufficient understanding between health professional and patient.10 Also, patients may not trust formally trained interpreters for a variety of social and cultural reasons, so again it is best to take your lead from the patient. If possible, a combination of the languages involved and nonverbal signs might be the best alternative when a patient refuses a trained interpreter. The main goal is to find a neutral and accurate means of communicating across language barriers. 9

Choosing the right words is a special challenge when working with patients with changes in mental capacity such as patients with Alzheimer’s disease. In a study of caregivers who worked with patients with Alzheimer’s disease, a “yes/no” or forced choice type of question (e.g., “Do you want to go outside?”) rather than an open-ended question (e.g., “What would you like to do?”) resulted in more successful communication.11 Family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease also found that using simple sentences was more effective than other communication strategies, such as slow speech.12

Thus, as always, the general rule has exceptions, and you will have to assess what types of questions work best with each patient. Of course, the way to respectful communication is to try as much as possible to talk to patients as equals (because that is what the majority of patients want) while remaining flexible in your style to meet individual patients’ needs.

Problems from Miscommunication

Several problems arise when miscommunication occurs because the health professional is unable to communicate with the patient in terms understandable to him or her.

Desired Results Are Lost

The health professional attempts to understand the patient’s complaints. Often the descriptions are too vague or too difficult to classify. Rather than continue to work to understand the symptoms and their significance for the patient, the health professional immediately turns to the more objective criteria of laboratory and other diagnostic findings and bases treatment programs on experience described in the literature or derived from a large number of other patients. This “miss” in communication all too often inhibits the results the health professional wished to achieve and could have achieved, had effective communication with the patient been established.13 Once again, when the health professional viewed the interaction with the patient as merely the transfer of information, the opportunity for true discourse was lost.

Meanings Are Confused

Another common area for miscommunication is when the health professional and patient are both using the same word but ascribe different meanings to it. In a qualitative study of diabetic patients and their physicians, it was found that different conceptions of the term “control” affected the ability of patients and their physicians to communicate effectively.14 Although the physicians in the study acknowledged the numerous physical, psychological, and social obstacles to treatment, they did not focus on these aspects of the disease when they interacted with patients. Rather, they focused almost entirely on managing blood glucose numbers. This led to a great degree of frustration on the part of the patients.

Doubt Arises about the Health Professional’s Interest

Another problem that can result from using technical language is that the person to whom you are speaking will not be convinced that you really want to know how he or she feels. In addition, your choice of words can unintentionally hurt the patient. For example, after her first prenatal visit to the doctor, a pregnant teenager reported to her friends, “The doctor wanted to know about my ‘menstrual history.’ I didn’t know what that was. Finally, I figured out she was talking about my periods. Why didn’t she just say that? I felt so stupid.”

When the health professional persists in using “big words” or technical language, the patient may interpret this as a sign that his or her problems are not important. The complexity and impersonality of a health facility will undoubtedly be communicated to the patient if health professionals are unwilling to explain carefully to the patient, in understandable terms, his or her condition and its treatment. The amount that is accomplished within any allotted period of time, rather than the actual amount of time spent, will convince the patient that the health professional really cares. If the patient cannot understand what is being said, little will be accomplished.

The mastery of appropriate vocabulary, then, includes being able to communicate with your colleagues but at the same time being willing to converse with patients in words they can understand. You will, in essence, need to become “bilingual,” translating from professional terms to common everyday language. When this is accomplished, it is more likely that the patient will be able to do what is requested, will respond accurately to your questions, and will be convinced that you care about him or her.

Clarity

In addition to using words that are too technical for the patient to understand, a health professional may not speak with sufficient clarity to free the patient from uncertainty, doubt, or confusion about what is being said. What is the difference between the two? Lack of clarity can result if you launch into a lengthy, rambling description of treatment options (e.g., not realizing that the patient was lost at the outset). Even a highly organized, technically correct, and objectively meaningful sentence can be unclear if it is poorly articulated or spoken too softly or hurriedly. Lack of clarity can result when patients become preoccupied with one particular facet of what you are saying and consequently interpret everything else in light of that preoccupation.

It is surprising to some students that patients may be too embarrassed to ask them to repeat something, and so patients rely on what they think they heard. Patients are sometimes hesitant because they are a bit awed by you as the health professional and so try to act sophisticated instead of asking you to repeat what you said. Patients may be awed primarily because they realize that health professionals have skills that can determine their future welfare and that, regardless of their influence in the business or social world, they are at your mercy in this situation. Some ways to help enhance the clarity of your communication follow.

Explanation of the Purpose and Process

Clarity begins with helping the patient understand why you are there and what you plan to do. As we mentioned earlier in this chapter, you first establish the purpose of your interaction when you introduce yourself and explain your role. This general introduction should be followed by a statement of the purpose of this particular encounter (i.e., what is going to take place at this time and why). Thus, you and the patient know what the goal of the interaction is from the start. Because the patient may be tired or uncomfortable, it is also helpful to state at the outset how long the interaction will take and what the patient will likely experience (e.g., “The head of this instrument may be a little cold at first when it touches your skin,” “When you get up on the table we will ask you to roll onto your right side,” and “Push this call button if you want to get out of bed.”). Questions the patient asks will then help you decide what more you need to say.

Organization of Ideas

Think ahead about how you are going to present your information. You can quickly confuse a patient by jumping from one topic to the next, inserting last-minute ideas, and then failing to summarize or to ask the patient to do so. Failure to systematically progress from one step to the next toward a logical conclusion is usually caused by (1) your own lack of understanding of the subject or of the steps in the procedure or (2) ironically, a too-thorough knowledge of the subject or procedure. The former causes the patient to have to figure out the relevant facts, whereas the latter causes the speaker to leave out points that are obvious to him or her but not to the listener. In either case, it is advisable to organize the description of a procedure or test into its component parts and then to practice describing it to a friend who is not familiar with the procedure. That person will be able to identify any obvious steps that have been omitted. Complicated information should be broken down into manageable chunks so that the patient is not overwhelmed by everything that follows. This is especially true when the information involves bad news.

Augment Verbal Communication

Verbal information and instructions alone are not always adequate to ensure clarity. Written notes or instructions, diagrams, videotapes, and nonverbal demonstrations are highly desirable adjuncts to the spoken word because they may help the person organize the ideas and information more fully.

Tone and Volume

Paralinguistics is the study of all cues in verbal speech other than the content of the words spoken. Although paralinguistics is considered part of the realm of nonverbal communication, we will discuss tone and volume here because they are so closely connected to the content of speech. Sometimes a person’s voice or volume belies his or her words. Any vocalized sound a person makes could be interpreted as verbal communication, so besides your words you will communicate “volumes” with the tone, inflection, speed, and loudness of the words you use.

Tone

Each of us tries to communicate more than the literal content of our messages by using different tones of voice of the same spoken message. An expression as short as “oh” can be used to express anger, pity, disappointment, teasing, pleasure, gratitude, exuberance, terror, superiority, disbelief, uncertainty, compassion, insult, awe, and many more. Try this exercise with “no,” “yes,” and other simple words or phrases to fully grasp the rich variety of meanings a word can convey when you vary the tone and inflection.

Tone is a voice quality that can actually reverse the meaning of the spoken word. When the patient’s response is puzzling to the health professional, the latter should be alert to the tone in which the patient communicated a message or reacted to a statement. For example, if the patient asks, “Am I going to get better?” the health professional can inadvertently confirm the patient’s worst fears by hesitating then answering in a not-too-convincing tone, “Why, of course you will.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree