Respect in the Institutional Settings of Health Care

The VA Medical Center was wonderful and exactly what I needed, but, as I was repeatedly told while I was there, “This isn’t a hotel. You’ll have to work here, but this is a good hospital.”

M.E. Little1

Chapter Objectives

• List four major forces that have resulted in current structures of health care environments

• Compare relationships within total institutions and partial institutional environments

• Discuss the idea of patients’ rights documents and the purposes they are designed to serve

Chapter 1 addressed important aspects of being a professional. This chapter focuses on some key insights regarding where you will exercise your professional skills. You will almost inevitably work in an institutional environment, which exists to provide health care services. Your ability to understand and respect this basic structure and its operations is essential to your work satisfaction and also will determine how you are viewed by patients, colleagues, and others.

Some of you have seen paintings by the French impressionist painter Marc Chagall. He creates a heavenly environment evoking romance, bliss, and promise (Figure 2-1). His work speaks to a deeper meaning: Our environments always create certain expectations and evoke powerful feelings. They influence attitudes and conduct in ways that we are not always consciously aware of or do not fully understand. It follows that every reader of this book will be influenced by his or her work environment, as well as influence it by participating in its everyday activities. A good starting place for respectful interaction, then, is to become familiar with basic characteristics of such institutions and then address key characteristics of institutional relationships within them. It will also benefit you at this point to become aware of some key policies and practices designed to command respect from all who engage with the institution, whether employees or those seeking goods and services, so we introduce them in a general way in the final sections of this chapter.

Characteristics of Institutions

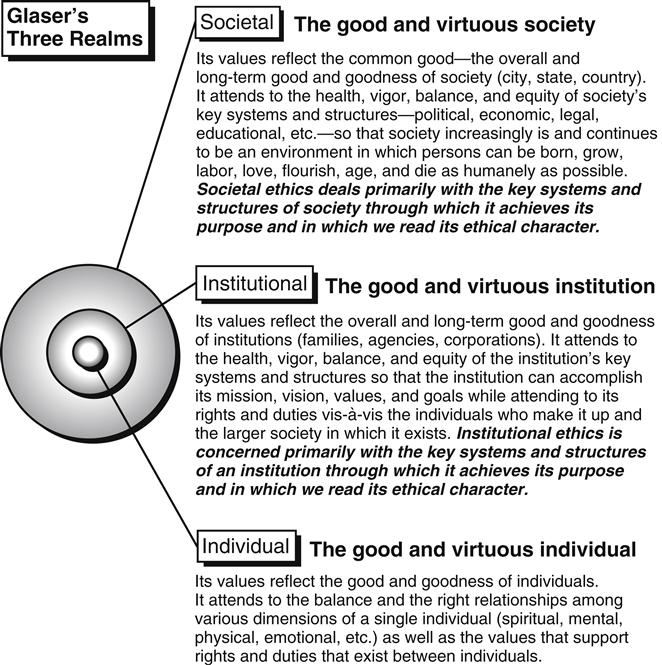

Glaser describes three realms of social activity—individual, institutional, and societal—each having an impact on the health professional’s effectiveness and sense of well-being. Institutions sit at the interface between the individual and the larger society (Figure 2-2).2

Ideally, institutional policies and practices reflect deep respect for values that guide individual health professionals personally and professionally but also encourage them to be responsive to the basic societal expectation that patients are the top priority. In turn, health professionals will not only engage in respectful interpersonal relationships with patients and families but also be loyal and respectful of management and administrative policies of the institution. We do not live in an ideal world, thus at times challenges arise among the priorities and values in the three realms.

Diversity of Facilities

The institutional realm of health care is a complex web of ideas and values expressed in numerous types of health care facilities. Health professionals work in hospitals, ambulatory care clinics, nursing homes, long-term care facilities, rehabilitation settings, research centers, diagnostic laboratories, schools, hospices, industrial settings, spas, and military first response units; among sports teams; and on cruise ships, to name a few. What is fitting for one type of facility may look quite different from another.

Moreover, the organization of health care is not completely a rational system. Rational systems are oriented expressly to the pursuit of one specific goal and have a highly formalized social structure designed to meet that goal.3 An example is an airport, where the single goal is to move people and goods from place to place. The institutions of health care can be more illustrative of an open system in which shifting and sometimes competing interest groups negotiate for their goals to be met. At the same time, some silver threads of commonality among health care institutions will help you understand your work environment. For instance, they share some key values including:

![]() Autonomy, freedom from undue outside regulation

Autonomy, freedom from undue outside regulation

![]() Social justice for underserved populations

Social justice for underserved populations

![]() High quality service in response to health needs of the community

High quality service in response to health needs of the community

![]() Loyalty to shareholders in institutions that operate as a business

Loyalty to shareholders in institutions that operate as a business

When you enter a program of professional preparation, the basic type of institutional setting where you will work may be determined in part by the focus of your profession. For example, a focus on maintenance and health promotion may mean you will practice in a health spa, school, industry, or free-standing clinic that provides wellness education. If you are drawn to acute care, rehabilitation, chronic health, or end-of-life care needs, it is likely you will find work in a hospital, rehabilitation center, nursing home, hospice, or in home care.

Multi-Service, Team-Oriented Institutional Environments

Most health care organization in the United States, Canada, Europe and Great Britain today reflect the trend toward comprehensive complexes housing “health plans” and away from institutions with one particular function. This approach represents a move toward more population-based models of care with a defined target population of patients and their health needs (Figure 2-3). Many have commented on this movement in the 20th and 21st centuries, identifying it with the following:

Institutional environments have changed and will continue to do so during your professional career. Attention to where you find the best fit for your practice will require attentiveness to changing styles and designs of institutional environments.

Characteristics of Institutional Relationships

The ability to show and receive respect in the work environment requires an understanding of several characteristics of relationships that take place in health care institutions compared with other types of relationships. To highlight this point we examine two characteristics of health care institutions that distinguish them from some others you participate in, namely their public rather than private nature and the institution’s role as a partial rather than a total institution.

Public- and Private-Sector Relationships

Public-sector relationships are interactions reserved for engagements within institutions of public life, whereas private-sector relationships are reserved for the world of family, friends, and other intimates.3 Individuals generally separate their lives into these two worlds of relationship. Public-sector relationships are designed to serve a useful purpose and then dissolve, whereas private-sector ones are more likely to continue. Student and professor or patient and health professional relationships belong to the world of public-sector relationships. Social boundaries that are maintained in a public-sector relationship permit rapid introduction and rapid separation, promoting cooperation around a common goal. All public-sector relationships are characterized by abrupt changes from extreme remoteness to extreme nearness with the expectation that the relationship will be temporary. Students who become close during their years of formal preparation go their separate ways upon graduation. Professionals in attendance at a conference of their professional organization come from different worksites to learn, share their own research or expertise, enjoy socializing, and then depart back to their own practice settings.

Opportunities for involvement in each other’s lives and well-being and the boundaries of respect that must be honored with patients, families, and peers are addressed throughout this book, especially in Part Five.

The physical structure of an institution helps to enable an effective private- or public-sector relationship. Hospitals or schools, for instance, unmistakably are public buildings. What are some of the clues for this conclusion? Sometimes the environment where health care is administered mingles private- and public-sector environments. For instance, a lounge where patients who are institutionalized for long-term stays can meet often will foster private-sector friendships within the public-sector facility that will last beyond discharge. On a different scale, a home visit to a patient requires that you go to his or her residence, be welcomed in as a guest would be, make your way across the living room among discarded pages of the morning paper, trip over the sleeping dog, and move a bathrobe from a comfortable overstuffed chair to sit down. You have entered a profoundly private-sector environment. However, your presence and professional conduct represent the type of public-sector relationship that takes place within health care institutions and this usually suffices to adequately set the tone for measures that show appropriate respect for a public-sector interaction.

Increasingly computer-generated simulated environments are being added to the physical structures of care, raising interesting questions about what is required when the “institution” is a computer-generated one such as one finds in Second Life. Health professionals and patients interact as avatars but around therapeutic issues that affect them as “real-life” users of this technology. As you read this book reflect on how communications and other aspects of respectful interaction may be influenced and altered by this tool of interaction.

Relationships in Total and Partial Institutions

Another area of consideration about institutional relationships came from a now classic study of how authority is exercised in institutions. More than 50 years ago sociologist Goffman advanced an understanding of institutions on the basis of observations about the participants’ relative authority. He noted that the design of institutions enhances the way authority is exercised and by whom, dividing the structural arrangements into “total” and “partial” institutions.4 To illustrate, recall your experience in a campus dormitory, airport, hospital, or other type of institution. Each has its physical design and function accompanied by certain rules, regulations, policies, and other constraints. We judge such constraints as legitimate if they seem to serve understandable goals of the institution.

Total Institutions

Total institutions are those in which personal autonomy is totally or seriously compromised by the persons who voluntarily or involuntarily are placed in the structure. They are places where, as Goffman describes it, “a large number of like-situated individuals, cut off from the wider society for an appreciable period of time, together lead an enclosed, formally administered round of life.”4 Usually professional and supportive personnel are the sole authority: They “run” the institution, and the assumption is that either the individual or society (and in some cases, both) benefit from the arrangement. Often a ritual act of donning the clothing of the institution (e.g., a nun’s habit in a cloistered convent or a prison jumpsuit) further signifies the surrender of identity and autonomy and “the acquisition of a new identity oriented to the authority of the professional staff and to the aims and purposes and the smooth operation of the institution.”4 Although their functions vary, examples of total institutions are many: monasteries, nursing homes, locked Alzheimer’s units, long-term care facilities, hospitals for severely mentally ill or developmentally challenged persons, and prisons.

Only a small percentage of health professional and patient interactions take place within the highly codified and rigid structure of a total institution. When they do, the patient’s autonomy is lost or diminished by illness, injury, lack of decision-making capacity, or some social factor such as committing a crime. In this situation of uneven authority, every precaution to respect the dignity of the person must be rigorously undertaken. Recognition of the vulnerability of such persons to abuse at the hands of even well-meaning individuals often necessitates writing special precautionary guidelines and policies for health care. For instance, there are especially stringent guidelines for protecting persons in such environments from abuses carried out in the name of clinical research.

At several places in this book, particularly in Part Three, we revisit the idea of turf, those aspects of a personal living space and self-determination that can help to lend dignity in the midst of serious constraints as a result of health-related confinement to an institution.

Partial Institutions

Most health care institutions can be classified as partial institutions because they constrain patients’ autonomy in some important ways but also allow for varying degrees of self-determination.

People entering such institutions are concerned about the potential constraints they will face.