Respect in a Diverse Society

Anyway, the patient will die, so what is the use of saying you are going to die of cancer, right? The doctor should say, “You are okay; you will be fine … Just take the medicine, which will get you better.” He shouldn’t say that you have cancer, so you will die in a few months. Isn’t that common sense?

Korean-American Senior Citizen1

Chapter Objectives

• Define cultural bias and personal bias

• Identify three sources of personal bias that interfere with respect toward persons or groups

• Define prejudice and how it is related to discrimination

• List primary and secondary characteristics of culture

• Describe ways that the label of “race” is problematic even though it continues to be used

The first two chapters discussed the value context of individuals, as persons and professionals, and the institutional environment. Respect also involves sensitivity to individual and group differences. Thus, you may discover that, even with deep understanding of your personal values and clarity about the goals and values of the place where you work, respectful interaction still does not result. Yet to be considered is the fact that each person interprets actions, facial expressions, choice of words, and other forms of communication according to his or her cultural conditioning, past experience, and social context. All of these interactions take place within a society that, at least within the United States, has long been described as a “melting pot” in which all of the various cultures and beliefs blend together. The melting pot metaphor hides the negative side effects of such a view of American society that forces assimilation, which strips immigrants and refugees of long-standing cultural traditions and practices. Although some still hold to the melting pot description of the United States, others claim it is no longer accurate and that it is more like “chunky stew,” a stew savored both for the character of the individual ingredients (ethnically derived differences) and for the delicious melding of flavors (social integration).2 Others countries, such as Canada, have traditionally likened society to a “vertical mosaic” with each person comprising an integral part of a complex but comprehensive picture.3

Furthermore, members of cultural groups can individually or collectively adapt to or borrow traits from other cultures, which is quite common when members of diverse cultures are in prolonged contact.4 The phenomenon of merging cultures is called acculturation. In this chapter, we examine some of the cultural and social differences you will encounter in clinical practice and the barriers (e.g., personal and cultural biases, prejudices, discrimination) that get in the way of appreciating differences and inhibit respectful interaction.

Bias, Prejudice, and Discrimination

A cultural bias is a tendency to interpret a word or action according to a culturally derived meaning assigned to it. Cultural bias derives from cultural variation, discussed later in this chapter. For example, some cultures view smiles as a deeply personal sign of happiness that is only shared with intimates. Others view smiles as an indication of general friendliness to be shared with any and all. It is quite possible that another can interpret a friendly smile on the part of one person as disingenuous or inappropriate. Regarding health care, attitudes toward pain, methods of conveyance of bad news (such as the seemingly contradictory statement at the outset of this chapter by a Korean-American senior citizen), management of chronic illness and disability, beliefs about the seriousness and causes of illness, and death-related issues vary among different cultures. These different kinds of beliefs about disease and illness have an impact on health care–seeking behavior and acceptance of the advice, status, and intervention of health professionals. Understanding a patient’s concept of health and illness is critical to the development of interaction strategies that are clinically sound and acceptable to the patient.

A personal bias is a tendency to interpret a word or action in terms of a personal significance assigned to it. It is found largely in what is commonly called prejudice. Personal bias can derive from culturally defined interpretations but can also originate from a number of other sources grounded in personal experience. The individual internalizes the cultural attitudes until he or she believes them to be entirely personal. Put another way, a personal bias is an individual’s feeling about a particular person or thing that colors his or her interpretation of it. The bias can lead to more favorable or less favorable judgments than are deserved. This process is similar to that of internalizing societal values described in Chapter 1.

Understanding the way personal biases influence us and their effect on our attitudes and conduct are important to the health professional. Whenever bias is present, it affects the type of communication possible between the persons involved and therefore must be recognized as one determining factor in respectful interaction. In some cases, personal bias may produce a positive bias or “halo effect” on certain individuals; that is, a single characteristic or trait leads to positive, global judgments about a person. For example, a patient who is pleasant and cooperative during office visits could also be thought to be compliant with therapy because of the halo effect even though the opposite could be true. Although showing favoritism on the basis of personal bias alone is not permissible in the patient and health professional relationship, common interests can, of course, have legitimate positive effects on the relationship between two persons working together and thus improve the health professional and patient interaction.

Discrimination is negative, different treatment of a person or group. Usually it is derived from prejudice. Prejudice is “an aversive or hostile attitude toward a person who belongs to a group, simply because he belongs to that group, and is therefore assumed to have objectionable qualities ascribed to that group.”5 In this way we see how prejudicial attitudes manifest themselves in discriminatory behavior.

In short, every exchange between a patient and health professional undoubtedly will be influenced by cultural differences and other sources of personal bias. Sometimes these feelings will create an attitude of prejudice and a desire to discriminate. In Chapter 2, you were introduced to some of the laws that help define the legal limits to which discrimination can be pushed within the health care environment. However, despite legal guidelines, discrimination occurs craftily and evasively. You must watch for it in yourself and others because both parties involved are inevitably injured by the interaction. Gordon Allport, in his definitive work, The Nature of Prejudice (which, although written over 50 years ago, is still widely considered an authoritative study), warns, “It is a serious error to ascribe prejudice and discrimination to any single taproot, reaching into economic exploitation, social structure, the mores, fear, aggression, sex conflict, or any other favored soil. Prejudice and discrimination may draw nourishment from all these conditions and many others.”5 It should be emphasized that treating people differently because of race, religion, ethnicity, gender, or other attributes does not necessarily imply prejudice and discrimination. Respect for differences includes understanding when those differences should count, how they inform the responses of people, and the process of providing patient-centered care.

What can you learn from the previous pages? One thing you can discern is that the cultivation of respectful attitudes and conduct begins with self-examination and consideration of what cultural differences mean to you. This is not as easy as it may seem at first glance. It requires that you enter into a “difficult dialogue” (i.e., you are asked to reconsider long-held assumptions about individuals and groups that raise questions about your values and beliefs). Engagement in this type of activity may lead to feelings of discomfort and uneasiness.6 These uncomfortable feelings result from the limited experience most of us have in interacting and talking with individuals different from ourselves.

We explore here a variety of differences, both obvious and subtle, that exist between people, such as differences in language, one of the most basic reasons for miscommunication—why, for example, even when we speak the same language, we may hear what a patient says but not understand its true meaning. Once you become aware of your often unconscious biases, you can more easily avoid being controlled by them in your interactions with others. Furthermore, by becoming aware of your hidden biases, you will be less likely to form inappropriate judgments about patients, colleagues, and others and more likely to remain sensitive and open to differences that influence your interactions with them.

Respecting Differences

A cursory look around almost any community in the United States or most other countries would indicate that we live in multicultural societies. Some assert that we are all “ … multi-cultural beings—living in worlds of multiple cultural identities. We are born into one world, and perhaps as adults live in another world where we move between cultural references of family, work, and community.”7 Sensitivity to cultural differences today has increased owing to the various underrepresented minority rights movements over the past several decades and the ever-growing percentage of ethnic minorities in the United States. In fact, in 2011 for the first time in U.S. history, babies born to ethnic minorities outnumbered the number of white toddlers.8 According to the 2010 census, the national population was approximately 308,745,538; of this total, 16.3% self-identified as Hispanic or Latino; 12.6% as black or African American; 4.8% as Asian; and about 1% as American Indian, Alaskan native, Hawaiian native, or Pacific Islander.8

Clearly there is growing diversity on a national basis, but this change in the composition is also felt on the local level within urban and rural communities. Perhaps the shift in the makeup of the population is felt even more strongly in rural areas in which the arrival of refugees and other immigrants seeking jobs has dramatically changed the homogenous nature of communities. This growing diversity also has strong implications for the provision of health care. There is a significant underrepresentation of minorities in the health professions, which contributes to the disparity in the health status of minority groups—African Americans, Hispanics, Asian Americans, American Indians, Alaskan natives, Hawaiian natives, and Pacific Islanders. “A singular challenge facing health care institutions in this century will be assisting an essentially homogeneous group of health care professionals to meet the special needs of a culturally diverse society.”9

Depending on where you live, you may be more or less aware of the percentage of persons from cultural, ethnic, and racial backgrounds that are different from your own who are living in your community. One way to identify the various cultural groups in your area is to use data from the U.S. Census Bureau, which is organized by state, county, and towns with populations greater than 5000 people. You can access the most recent information by going to the home page of the U.S. Census Bureau (http://quickfacts.census.gov). There you can find the cultures represented, the languages spoken, and other information about where you live and work.

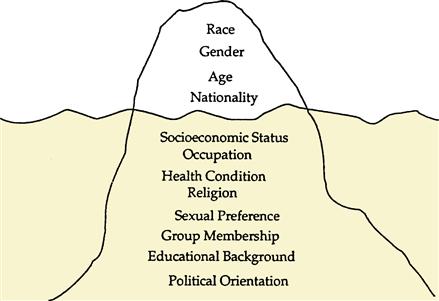

In almost every health care setting, you will interact with patients of backgrounds different from your own. Certain differences are obvious; others are hidden. The iceberg model illustrates how much remains below the surface in our interactions with others (Figure 3-1). For example, we may quickly notice that a young woman is wearing a burka and come to the conclusion that she is Muslim, but we may not as easily know what practices of her faith or her culture could affect health care decisions (Figure 3-2). Health professionals generally believe they know a patient’s race or gender merely by interacting with a patient, but, as you will see from further discussion in this chapter, we may not be as accurate as we think in determining exactly who the person is sitting in front of us. With this limited information about potential differences, a professional can adjust communication patterns and approaches accordingly. However, it is more difficult to assess a patient’s socioeconomic status or place of residence, two differences that can have as profound an effect on a patient’s health beliefs or behavior as do visible attributes such as age and gender. The differences that are hidden may create more stress than those that can more readily be identified.

Even with experience, you may sometimes fail to appreciate significant differences in others with whom you interact. It is a continual challenge to look below the surface at the differences that affect interactions with patients and devise strategies to overcome barriers and facilitate communication. Many such differences have come to be viewed collectively as being characteristics of a person’s “culture.” However, just exactly what “culture” is or how the concept is to be used in health care interactions is open to a variety of interpretations. A broad definition of culture is the beliefs, customs, technological achievements, language, and history of a group of similar people.10 A more nuanced understanding of culture is as follows:

My position is that culture is a useful analytic category, provided it is understood as ubiquitous and intrinsic to all social arrangements. The concept encompasses local, tacit, largely unquestioned knowledge and practices, but aspects of culture can be debated, disputed, and put to work for political ends.11

So you can think of culture in terms of primary characteristics such as race/ethnicity, gender, and age and secondary characteristics such as place of residence, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status that are all part of the web of social interactions in daily life. Cultural practices and beliefs can have a significant effect on the following health-related issues: diet, family rituals, healing beliefs, understanding of illness and causation, communication process and style, death rituals, spirituality, values, art, and history. Because culture has such a broad impact on health and because of the increasing diversity in the United States, “cultural competence has gained attention as a potential strategy to improve quality and eliminate racial/ethnic disparities in health care.”12 We turn your attention to a difference that is the root of numerous conflicts between social groups—race.

Race

Race is one characteristic of culture almost always mentioned in discussions about cultural differences and is perhaps the characteristic or descriptor most fraught with controversy. However, even the distinctions used by the U.S. Census Bureau constitute a system based on outmoded concepts and dubious assumptions about genetic difference. The 1999 Institute of Medicine Report edited by Haynes and Smedley stated that in all instances race is a social and cultural construct based on perceived differences in biology, physical appearance, and behavior.13 An editorial in Nature Genetics flatly stated, “Scientists have long been saying that at a genetic level there is more variation between two individuals in the same population than between populations and that there is no biological basis for race.”14 If the biological understanding of race seems to have been settled, that is not the case. Postgenomic science has revived the idea of racial categories as proxies for biological differences and with it a revival of controversy and new opportunities for discrimination.15 At a minimum the present idea of race clearly has social meaning because it assigns status, limits opportunities, and influences interactions between health professionals and patients.16 Take a moment to reflect on the race categories listed in Box 3-1 that are presently being used to classify people by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The same difficulty with racial identification can occur with your patients as well.

Although it is generally true that patient treatment and counseling are more effective when obtained from members of one’s self-identified racial group, it does not mean that patients must always be treated by members of the same race to receive quality care. First of all, this would not be possible because there are so few health professionals who are underrepresented minorities. Second, it is possible to learn how to appropriately work with patients different from our own racial and ethnic backgrounds through sensitivity, knowledge, and skills in cross-cultural communication.

There are other barriers to be overcome between patients and health professionals that are, unfortunately, deeply tied to notions of race. In a national study conducted by the Institutes of Medicine on disparities in health care, evidence indicated that stereotyping, biases, and uncertainty on the part of health care providers can all contribute to unequal treatment.18 Additionally, there are ample historical reasons for members of minority populations to mistrust the health care system. For example, in the not-too-distant past, African American patients were refused treatment at “white-only” hospitals. Some were undertreated and deceived in the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study. Mistrust in the health care system on the part of African Americans continues to this day because of these historical events and continuing discriminatory events in health care.19 Gaining the trust of patients whose racial identity is different from one’s own is a challenge but not an insurmountable one if a health professional can show that his or her aim is to be “trustworthy” so as to be able to provide optimal care and minimize and eventually eliminate disparities in care.

One of the first steps in reducing disparities in the health care setting is to be aware that they exist. For example, not long ago one of the authors participated in an ethics consultation regarding an extremely ill newborn. The African American parents of the baby looked around the table of health professionals gathered for the meeting. The father quietly commented, “I’d feel a whole lot better about this if there was one other black face besides the two of us at this table.” Although all of the health professionals present were there for the good of the baby and his family, the lack of representation of someone of the parents’ self-identified racial group was a significant barrier to the discussion and, ultimately, to the decisions made. If the father had not made the comment, the health professionals involved probably would never have noticed the circle of white faces surrounding the parents.

The preceding example indicates that there may be justifiable reasons to consider social categories of race when making clinical decisions. Another situation in which race (and ethnicity) may be a reason for differential treatment is when certain medications are prescribed because both can, in certain cases, affect disease pathophysiology and drug metabolism.20,21 “Certain genetic variations may well correlate with groups whose ancestors lived in particular regions (e.g., the sickle-cell trait is found in areas of western Africa, the Mediterranean, and southeast India, where malaria has long been prevalent). These correlations can help in identifying and treating diseases.”22

Race and ethnic background can also influence dietary habits and other activities of daily living that have a direct impact on health care outcomes. Although different treatment based on race or ethnicity may be justified in special cases such as those mentioned, it is the exception, not the rule. You must remain alert for unjustified differences in care based on race or ethnicity.

Gender

Gender issues interact with other primary and secondary characteristics of culture to shape a person’s identity. There are many implications for assessment and treatment of patients based on differences in gender. Gender inequities in health status and health care access exist worldwide and are strongly related to other social determinants of health such as education and economic status. Women in developing countries often lack access to basic health care and suffer from domestic violence and murder at a higher rate than their counterparts in countries with more education and economic resources.23 However, even in the relatively affluent United States, women have a history of unequal access to sources of economic and political power that impacts access to health care resources.24 This is especially true for African American women or older women who experience the combined impact of race, gender, and age discrimination. Gender inequities in health care are inexcusable but often subtle and unfortunately widespread. At the same time it is also important to simultaneously acknowledge differences that should be taken into consideration and accommodated in planning and delivering care.

Let us take as an example the preferences of patients regarding the gender of their physician. Numerous studies have documented the fact that 20% to 56% of women explicitly prefer a female physician for women’s health problems.25,26 Because many women feel uncomfortable and perhaps embarrassed during a gynecological examination, they may prefer female physicians because they are familiar with the female body and have firsthand experience with the examination. If women are more comfortable with the examination, then they will be more likely to follow through with checkups and follow the recommendations of the physician. A recent study shows that outside of the specialty of obstetrics and gynecology, communication skills was the most important factor for women patients regarding their interaction with a physician.27 The challenge for all health professionals is to adopt behaviors and communication styles to compensate for any differences from their patients.

A patient’s preference for a health professional of the same gender may not only be a personal but also a cultural or religious one. Many cultural groups are concerned about modesty and may require that only a female health professional examine a female patient’s genitalia or be present when the patient is undressed. Gender differences regarding modesty can have direct implications for diagnosis and treatment, as is evident in the following case.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree