Respect for Yourself during the Student Years

“I’m a student nurse,” I began by way of introduction. “Could we sit down somewhere and talk?”

Ann led the way with shaky steps to a small table and two chairs. Ruth followed us and stood behind her mother and played with her necklaces.

I asked Ann, “How long have you had this shakiness?”

“Started 2 days ago,” Ann replied.

“Has this happened before?”

“Sometimes, but not this bad.”

I had seen a few patients react to antipsychotic drugs this way, but not this severely. At least I thought it was a reaction to the medication. Maybe Ann drank as well—I didn’t know how to ask her if she did. …

—A. Haddad1

Chapter Objectives

• Explain what competence involves as a criterion for becoming and remaining a qualified practitioner.

• Identify four types of skills associated with professional practice that students must master.

• Name eight steps in acquiring skills needed for work in the health professions.

• Evaluate several sources of student anxiety and some methods of addressing it effectively.

Health professionals throughout their careers are faced with unexpected questions that arise in the course of treating patients. In the above anecdote the student nurse has the added test of being a student with limited hands-on experience in interviewing situations and also in confronting the range of symptoms a patient may have during an antipsychotic drug reaction. In this chapter we take the opportunity to focus on a special portion of a professional’s life span, the student years of formal professional preparation, noting some special issues and challenges that arise by virtue of being in that phase of professional development. At the same time we are quick to remind readers that a professional career is one of lifelong learning, so some challenges first encountered in formal professional preparation arise again and again during the course of a professional’s career. The need for practitioners to remain on top of ever-changing developments in health care is a compelling reason that most health professions organizations and licensing bodies require evidence that a practitioner has participated in continuing education activities.

We begin this chapter by standing back from some specific aspects of your educational process to first examining the more fundamental question of how you can be caring of yourself during the student years and make physical and psychological space for your optimal functioning. Both are examples of how nurturing yourself will support self-respect that will serve you well throughout your career.

Sustaining Self-Respect through Nurturing Yourself

Nurturing comes from root words meaning feeding, taking loving care of, and bringing into full bloom. So nurturing yourself is not limited to addressing worrisome problems such as anxiety. In Chapter 1 you were introduced to the idea that a life guided by respect depends in part on the ability to identify and shape one’s own life according to personal values and those that help to build a stronger community. The basic question we ask for your reflection is, “What kinds of attitudes and activities can you cultivate during your student years to stay authentically you—healthy, happy, satisfied with your job, and able to integrate your professional and personal values and goals?”

There is the basic question of who is responsible for your well-being. Today the general consensus is that individuals ultimately are responsible for their own health. Do you agree? It certainly is the case that people feel better, look better, and are able to function more fully when nurturing their own sense of well-being, seeking balance in their lives, and mapping a life course that has opportunity for changing priorities. None of these goals ever comes easily! For example, studying for your professional degree means giving up other patterns and pleasures, as well as dealing with competing responsibilities.

The positive results of keeping life-affirming habits, practices, and goals in the forefront of your life plan as new situations arise seem obvious. However, if you are among the millions who make New Year’s resolutions each year, you know that acknowledging the benefits of staying healthy physically, mentally, and spiritually and actually being successful in doing so are not the same. In this section, we offer insights and suggestions to help you succeed in staying happy and healthy.

Self-Respect and Self-Care

Here is that idea of care again! You were introduced to it in Chapter 1 in the following paragraph related to values needed in your professional practice:

… Everyone talks about care as a positive feature of human relationships. It is. But care has a much more serious function in sustaining them than often we acknowledge. It is the link we make with another human being in distress, taking their suffering and well-being into account. Reich associates true caring with what we decide to do when the chips are down. Often it is not limited to the warm sentimentality so often expressed on the inside of greeting cards. True caring requires us to choose among our priorities and may become a challenge or even a burden. Caring always requires involved concern about the specific barriers to the other person’s well-being and the action required to relieve them.

What do you notice about this statement? It is about care of others. Not surprising, is it, because a core value of the profession is caregiving, searching for how to provide a caring response to a patient’s plight. At the same time this emphasis on caring for others points to a deeper issue in the formation of a professional identity. The emphasis on caring for others is so deeply rooted in your professional formation that the care of oneself can easily get left out of the equation. In fact, many health professionals are so attuned to being care givers or care providers that they perceive themselves as immune to needing care themselves. This illusion begins in student years when pressures of study and achievement increase. Goethe, in his Elective Affinities, illustrates that everyone has a potential for organizing a world that fits his or her illusions: “And so they all, each in his own way, reflectingly or unreflectingly, go on with their daily lives; everything seems to have its accustomed course, for indeed, even in desperate situations where everything hangs in the balance, one goes on living as though nothing were wrong.”2

The illusion that in caring for others one need not pay attention to one’s own needs and life-affirming instincts can lead to deep wounds over time, distorting what it means to place the patient first. For instance, to override feelings of deep distress, the need for relaxation or other healthy activities may set a pattern that engenders inappropriate guilt when a decision honoring care of oneself is made. Medical historians tell us that the physician Galen suffered nightmares for the rest of his life owing to his feelings of guilt after he fled his inevitably dying patients during the plague of Rome to protect his own life and that of his family. The health professions have been slow to incorporate the importance of taking good care of yourself as a value, even though you are obviously in a better position to serve others well when you are acting from a position of personal strength gained through the self-respect that comes from taking good care of yourself.

In a word, self-care is part and parcel of good care giving. By looking at the statement again from Chapter 1, but this time thinking of it in terms of self care, you can get a fuller picture of what is at stake:

… Everyone talks about care as a positive feature of human relationships. It is. But self care has a much more serious function in sustaining me than often I acknowledge. It is the link each of us makes with our own inner selves in distress, taking suffering and wellbeing into account. Reich associates true caring with what we decide to do when the chips are down. Often it is not limited to the warm sentimentality so often expressed on the inside of greeting cards. True caring requires me to choose among my priorities and may become a challenge or even a burden. Caring always requires involved concern about the specific barriers to well-being and the action required to relieve them.

Note that none of this attention to the self deflects from the realization that being in a professional relationship with patients means putting their specific health-related needs at the center of your professional deliberation. At the same time, this self-care gives you a measuring rod of qualities that allow you to fully engage without being in a constant state of alert self-protection. To bring these ideas right down to your situation, take a minute to complete the following simple exercise.

This is a great start. However, we also stated the caveat earlier in this section that most good ideas remain in the realm of dreams or even “resolutions” that fall away. Starting with right now, take a few minutes to follow up on what you have just listed as some what’s and who’s that will help keep you in a healthful state during your student years.

Self-respect in the student years, then, requires self-care both at the level of identifying what is important to you and finding ways to follow it through into your everyday choices.

Striking a Balance between Socializing and Solitude

Following through on choices that demonstrate self-care requires setting a balance between being with others and having time to yourself for self-reflection. To fail to strike such a balance undermines the self-respect that you assiduously have honored in making choices that show you care about yourself. Most classroom and laboratory learning in educational institutions is accomplished in group situations including face-to-face or on-line discussion, and therefore invite socializing. E-mails, texting, and Twitter create apt opportunities for continuous interaction with others in and outside of the student environment. An important aspect of nurturing yourself includes an awareness of this fact of student life and what you can do to strike a healthful balance between it and the silence of solitude.

Socializing does of course yield both professional and important personal benefits. Of the former, the language often used in the description of what happens in the process of becoming a professional is that the person becomes socialized into this identity. Obviously “socializing” (i.e., prolonged, engaged exchanges) with teachers, other students, and the whole environment of health care all are integral parts of socialization and distinguish the study of the professions from that of, say, philosophy or literature. From the get-go the professions are preparing students to do something with others. The study of the humanities can be undertaken as an end in itself.

In addition, it goes almost without saying that personal benefits gained from informal socializing as leisure and relaxation activities are for most readers an essential component of their self-care.

Why, then, be concerned with the importance of striking a balance between constant interactions and reflective aloneness as a criterion of self-care during the student years? One compelling reason is that learning in the professions must prepare you for reflective practice, not just direct application of material you have absorbed. You will learn more about this in your studies, but basically the processes by which your classroom and initial clinical learning experiences are refined are through additional mechanisms of integration. Benner3 and others have shown that this process of going from being a clinical novice to becoming a clinical expert is a self-reflective dimension of learning. In self-reflection you fly solo and need time and open space to do so.

Moreover, personalities differ in their need for internal “quiet time” to grasp and integrate material.4 If you have not taken a personality inventory like the Myers-Briggs to help you become more aware of your problem-solving styles and strengths, it is a step of self-care you can take because so much of learning to become a competent professional involves aspects of problem solving. Even the most extroverted person needs some solitude if fulsome learning is to take place. In short, a vital strategy for flourishing during the student years and beyond is to strike a balance that includes both interaction and solitude. Because little is said in the health professions education about solitude as a resource for self-care and effective learning, we share these few thoughts about it with you.

Solitude is a positive, active state of being, although the experience of solitude is not identical to happiness and may even be “bittersweet” (accompanied by sorrow or anger); nonetheless, it is sought out as a need in itself, not foisted on one as a result of feeling rejected or “out of contact.” It is a form of self-respect realized by embracing the necessity of not always responding to other people whenever they need or want it. As one popular student commented when he began to turn off his cell phone for an hour each day, “I realized over time that I had been acting like a service organization by always interrupting what I needed to do to link up with someone else!” Unlike loneliness, which is a form of suffering, solitude can be wonderful.

Pooh Bear, the most reflective member of Winnie-the-Pooh’s community, sought solitude often (Figure 4-1). He understood that solitude is a time to be with yourself only, not with others, and to engage in reflections and activities that can better prepare you for relationships. Some people are active in their solitude, finding walking, jogging, biking, reading, or other solitary activities a time for reflection. Others prefer the stillness of meditation or just sitting quietly Pooh Bear style. Some ideas to help you make time for yourself include the following:

![]() Set a time and place and rigorously adhere to it.

Set a time and place and rigorously adhere to it.

![]() Become bold in identifying to others what you are doing.

Become bold in identifying to others what you are doing.

![]() Take notes on your reflections or keep a log of your activities.

Take notes on your reflections or keep a log of your activities.

In addition, you can help others to have their own time alone by learning to recognize this need in fellow students and encouraging it.

With this backdrop of self-care and some aspects of your environment you need to help realize it, we turn to other issues in your student years that could challenge your respect for yourself and offer suggestions for ways to support and enrich it.

Self-Respect and the Motivation to Contribute

Most students know that they would like to be able to make a contribution to others in society. It is a motivator for applying to an education program in the health professions and in itself a good reason for self-respect. Many psychologists, philosophers, and others have demonstrated that a life of satisfaction for most adults includes making a contribution that has benefit to others whether it is to one’s children and spouse, as a volunteer, or in the public workplace. We address this later in the book from the standpoint of your encounters with adult patients whose difficulties preclude them from performing their adult roles and the self-deprecation they can feel. Often, though not always, the choice of a professional career arises from a student’s experience of illness or injury and how he or she was helped by a professional whom he or she came to admire, or a friend or loved one was ill and dying and health professionals showed able assistance and compassion in caring for the person. Sometimes the desire to become a professional is based on a student’s recognition that he or she has a talent for being a good listener or a capacity for helping friends when they are in trouble.

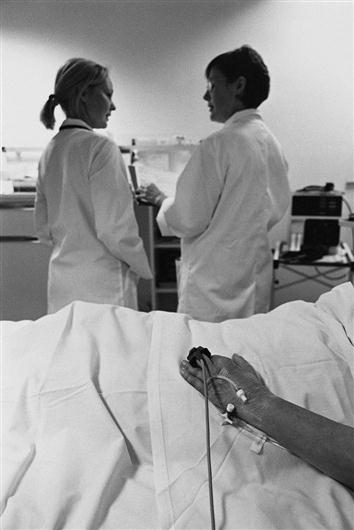

The desire to help others is not always the primary or only factor that leads people to choose a career as a health professional. Love of science, the desire to be in a “people-oriented” line of work, the desire for status, and a career that promises to provide a good salary and high satisfaction are other important and understandable motivators. However, the desire to make a significant contribution in life is important in helping you stay true to your course of study when the going gets rough. One good approach is to identify early on a teacher or other professional role model who manifests attributes you admire (Figure 4-2).