Respect for Challenges Facing Patients

Ten years ago, if I were setting out to make a film about catastrophic illness and subsequent disability, I would not have cast myself in the lead role. In my prestroke ignorance, I probably would have looked for someone stronger and braver than I—not yet knowing that we are all capable of much more bravery than we think.

—B.S. Klein1

Chapter Objectives

• Describe common conditions that create barriers to maintaining wellness

• Identify several types of privileges or accommodations patients may experience

Most challenges facing patients are related to their transition from everyday routine to the altered role that sick or impaired persons assume in society. The role includes physical, psychological, and spiritual challenges, whether the condition is short or long term. Fortunately, these challenges have received considerable attention in health professions literature and curricula in recent years, so it is likely that you will have one or more courses in which they are discussed. Some common themes are presented here as a basis for your ongoing thought and reflection.

Maintaining Wellness

It is fitting that a chapter on challenges to patients begins with some reflections on maintaining wellness because in recent years there has been much emphasis on maintaining and fostering a healthy lifestyle. Staying healthy seems to be to everyone’s advantage—the individual, his or her loved ones, and society. Wellness ensues from maintaining health-supporting habits over a lifetime. As you know, a healthy life ultimately depends on many things including a safe and health-inducing environment. Good nutrition, sleep, exercise, and other health-fostering habits are essential. Freedom from basic want and violence are essential, too. Today thousands of health professionals build practices on the basis of preventative approaches—teaching people some of the essentials of how to remain healthy. A few examples are nutritionists who are involved in school nutrition programs, nurses and nurse practitioners who may work in perinatal or other community education and screening clinics, physicians, and occupational and physical therapists and assistants who focus on safety and health maintenance in the workplace or hold positions in sports or recreational settings. A growing body of literature suggests that the mind and body can develop and grow stronger over an entire lifetime (Figure 6-1).

At the same time, lifelong healthiness is not a goal completely within an individual’s own control, even with the help of a safe and health-inducing environment. Almost weekly there are discoveries of new genetic predispositions to illness; scientists have identified scores of environmental toxins, and other health hazards are appearing on the horizon; many people live in conditions of poverty, lacking basic public health and safety conditions, while others suffer unavoidable work-related stress symptoms. Accidents and other misfortunes dash dreams, alter possibilities, and modify relationships. Moreover, most of us today have periods of less wellness or more wellness. For example, a person with mild pneumonia or late-onset diabetes or severe atherosclerotic heart disease may function mostly as a healthy person but still may need health care for serious symptoms related to the condition. At best, each of us moves through life on a continuum between maximal health and life-threatening illness or death.

Respect for Patient’s Health-Related Changes

The transition from being relatively well to becoming ill or impaired almost inevitably entails change in the form of losses. The loss may take the shape of decreased physical or mental function, as reflected in this excerpt from a young woman who has been working energetically to recover from stroke and then “bottoms out”:

One Saturday morning, you can’t bring yourself to get out of bed. Jim [her husband] hears you weeping, comes into the bedroom, and lies down next to you,

“What’s wrong?”

“I don’t feel like myself. I don’t want to get up and face another day in this damaged body. Everything is so hard and I’m just tired of trying to do basic shit, like getting dressed. I just don’t think I can live this way. I can’t do it.”

“Can’t do what? Get dressed? Come on, I’ll help you.”

“No. . . . I don’t think I can do all the things that I keep telling everyone I’m going to do. I think I’ve been saying I’m going to do all this stuff to convince myself. Jim, I can’t even put a sock on.”

This is not who you are. You feel even worse now because you have unloaded all your fears and insecurities on Jim. All he wants is positive energy from you, and you cannot even give him that. . . .2

Persons who lose their sight or other senses, those who lose control of movement or vital body functions, and those who through illness become incapable of making competent judgments may experience a similar sense of loss in some regards, in part due to society’s response to various conditions. The loss may also involve a change in physical appearance, such as the person who undergoes an amputation or is scarred after a severe burn.

The significance of these changes for each person is determined by a complex interweaving of several factors such as:

![]() the physical and emotional effects of the pathological process itself,

the physical and emotional effects of the pathological process itself,

![]() the alteration in the person’s environment or social roles, and

the alteration in the person’s environment or social roles, and

![]() the coping mechanisms the patient has developed throughout his or her life.

the coping mechanisms the patient has developed throughout his or her life.

Ultimately one cannot predict how a patient will respond. Experience of the significance of the loss is highly personal. Sometimes it is completely understandable to others. The concert pianist who loses an index finger in an accident will experience it as a more profound loss than most of us who might experience a similar trauma. Other times the effect on the patient baffles everyone. Patients will react to you in ways that express their concern about their losses. For example, upon entering a patient’s room, the phlebotomist may catch the brunt of the patient’s anxiety through comments such as, “Here comes the vampire!” The radiological technologist may be accused of destroying cells with the imaging equipment. Professionals whose diagnostic and treatment procedures require patients to engage in physical or emotional exertion can be accused of sapping a patient’s strength. These expressions of anger or fear reflect the challenge a patient is facing in trying to protect his or her body and sense of well-being from further loss.

Loss of Former Self-Image

A natural extension of loss of function or previous physical appearance is the feeling that one’s old self is gone. This is especially likely when physical or mental change promises to be prolonged or permanent. Recall the woman described earlier who wept because, “I don’t feel like myself. I don’t want to get up and face another day in this damaged body.” You have probably had the feeling sometimes that you just “weren’t yourself” that day or that what you did in a particular situation was not typical of the “real you.” For most people, this sense of self-alienation is temporary; however, it may become more long-lasting for a person experiencing significant losses associated with injury or illness.3

A patient’s feeling of having lost herself or himself may result in part from the conviction that one is largely determined by what one looks like. In other words, one’s self-image depends to a large extent on body image (Figure 6-2).

There is a close relationship between appearance, accompanying body image, and sense of self-worth.4 This is not surprising in a society with a multibillion dollar advertising enterprise stressing appearance above all else, and with it the idea of physical beauty and vitality depicted within narrow norms. Despite the proverb’s bidding, most of us still do “judge a book by its cover,” and the harshest judgments often are against oneself.

Have you encountered anyone today you thought was exceptionally fit, beautiful, or graceful? Our stereotypes of success and assurance of acceptance often depend on physical appearance. Painful sanctions are imposed on those whose appearance deviates too far from some societally determined standard of normality. A person who encounters illness or impairment must face daily the changes that depart from these stereotypes of success and beauty. The work that accompanies developing a new sense of one’s physical self after change in physical bodily appearance brought about by surgery has been explored by one of the authors through poetry:

FRENCH WEAVING

I piece together the tattered edges

with illusion net,

laying just the right size squares

over the gaping holes.

Carefully,

arduously

embroider the net to the original.

Trying to match the pattern,

tie up loose ends,

mimic the original curve and detail.

I pick up a thread

of who I once was,

try and attach it,

here,

here,

and here.

My clumsy attempts

only approximate the intricacy of the design.

Yet the untrained eye

cannot see my repair.

Run your fingers over my skin

to feel the flaws.

—Amy Haddad5

As you may expect, part of the health professional’s success depends on an adeptness at helping the patient either reclaim his or her old image as recovery occurs or, when necessary, discover a realistic and satisfactory new body image. Timing is one important element in your work with patients who are adjusting to changes in body image. There is no preestablished time frame for a man to accept his colostomy or a woman to look at the scar where her breast used to be. Each patient will move in his or her own way and at his or her own pace into this new life territory.

Respect for Necessary Changes in Patients’ Values

In addition to being able to identify one’s own and others’ values, it is imperative to recognize that everyone’s values change from time to time. The circumstances that force or enable most people to change their values usually evolve slowly, whereas those that force a patient to do so may appear in a matter of minutes or hours! Illness or injury almost always causes a patient’s and their loved ones concern about whether and how the person’s values will have to change.

The course of one patient’s evolving values is reflected in her response to her condition:

What types of values might Daniela have that would allow her to feel as if there is “much to live for” when so much has radically changed in her life?

The process of reclaiming and replacing values may take weeks, months, or years for any of us. The person who becomes a patient must learn what the illness or injury really means in terms of long-term impairment. Another woman who, like Daniela, had multiple sclerosis told one of the authors that it took her years to stop doing silly things that overstressed her. She said, “It was because I didn’t know my disease; now I know it, like a friend, strange as that may sound. Not knowing was the hardest part . . . ”

As we reiterate in later chapters, the success of adjustment and acceptance to inevitable change is based on the support of family, friends, and those treating him or her in the health professions. One of the greatest gifts you can offer is to be present as a person tries on a new identity with the values that will be fitting for the new situation.

Institutionalized Settings

Although not all people who become ill or injured spend time in hospitals or other health care institutions, the most seriously involved are admitted as inpatients. Inpatient is a term applied to those who enter a health care facility to remain there for a period of time.

The necessity of spending time confined in a health care facility may significantly disrupt an individual’s personal life, as well as the lives of family, occupational associates, and friends. The challenges associated with the disruption may be primarily social, but it is likely that they will also be economic, owing to loss of work, health care–related expenses, or both. The economic burden is especially acute for a person who is self-supporting or is the breadwinner in a family. A single parent has the burden of finding and paying for suitable caretakers for children. A child, teenager, or other student loses valuable instruction and may fall behind or have to drop out of school. A professional person may have to forego participation in an important project. Whatever the individual’s personal responsibilities, he or she is likely to be affected socially and economically.

Psychological stresses compound the social and economic ones. A person often believes that entering an institution for care signals that he or she is not winning the battle of coping with an illness or impairment. This psychological defeat can be as deleterious to his or her welfare as the physical manifestations of the illness itself. In submitting to confinement in an institution, the person finally is admitting openly that the problem is “out of control” and that people professionally qualified to provide certain services are needed on a continuous basis. The patient understandably is anxious about leaving his or her health, and perhaps life, in the hands of strangers but judges that there are no other good alternatives. Sometimes the awareness that the institutionalization took place because of severe stress on family and other caregivers adds to the discouragement.

Challenges Associated with Institutional Life

The disruption of daily and other normal life patterns and coping mechanisms that may accompany patients’ admissions is exacerbated by the fact that suddenly they are robbed of both home and important basic privacies. Therefore, having met the initial challenge of admitting to illness or impairment, patients now have to face other changes.

Home

Most people view their home as a safe haven in a complex, fast-paced world. Of course, there are some exceptions, notably people for whom home is a place of loneliness, strife, abuse, or boredom. Occasionally, a person will feign illness to be admitted to—or exaggerate symptoms to remain in—a health care facility just to escape threats to their well-being. These patients require special consideration by health professionals and are discussed later in this chapter.

What makes home so desirable for most people when they are away from it? The answer is that the majority of physical, psychological, and social comforts of home are missing in health care facilities.

Physical comforts take a number of forms. You have undoubtedly walked into someone’s room or home where everything is in incredible chaos and disarray. In the midst of the pandemonium, the person or family members appear perfectly at ease; this is their idea of really living! Undoubtedly, you have also entered a home where even the teacups seem to sit primly on shelves, where dust dares not settle, and curtains never ruffle. In the midst of this porcelain perfection, these family members also appear perfectly at ease!

The physical comfort of home may best be described as freedom to extend oneself naturally and completely into one’s immediate environment: to do (or not do) what one wishes, when one wishes, and how one wishes. The environment within the home, whether it contains 1 or 40 rooms, has been designed to conform to one’s own needs, habits, and desires.

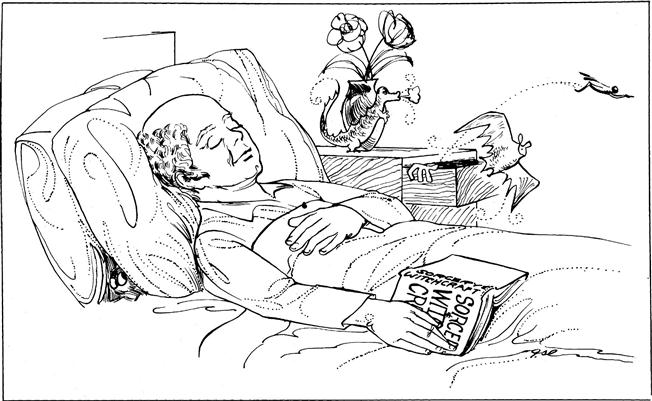

The bed is a good example of how health care facilities often are unable to adequately accommodate the needs and habits of a person. Almost anyone would agree that a good night’s rest greatly determines one’s outlook on life the next day, and most people acknowledge that their own bed is one of the most important comforts of home. The standard hospital bed is of a given height, width, length, and firmness. Although the hospital personnel stop short of treating patients in the manner of Procrustes, the culprit in Greek mythology who invited his guests to sleep in his guest bed and responded by chopping off the legs of those who were too tall, institutions are usually limited to offering a standard hospital bed.

The obvious difficulties of totally personalizing every patient’s health care setting are readily apparent. Hospice is a notable exception, with many hospices giving high priority to encouraging patients to have familiar objects around them. Many nursing homes and long-term care facilities become the final home to residents unable to return to their own dwellings. Many such facilities also are devoting much more attention to providing familiar, comfort-enhancing surroundings. The more that can be done to optimize physical comfort for the patient who is away from home, the more readily he or she will be able to direct energies toward healing, adjusting to dying from a life-threatening illness, or living with impairment.

Psychological and social comforts of familiar surroundings are also sacrificed with institutionalization. A favorite chair for relaxation, a magnifying mirror for applying makeup, a family picture, or a ragged toy may all be symbols of security to the person. The mere arrangement of furniture in a room or the sight of a tree or birdbath in the yard may give a person a sense of well-being. We are told that many patients, upon returning home, burst into tears upon being welcomed by a beloved pet or when noting that a flowerbed has blossomed in his or her absence. All too often these comforts are left behind when the person goes to a health care facility.

Psychological and social comfort may also be experienced in the routine associated with being “at home.” It is not at all unusual for a patient who enters a health care facility to become confused about what day of the week it is because important, regularly scheduled events are missing. The person who likes to start the day with a cup of coffee and the morning paper will be unsettled when, in a health care facility, the coffee is served with breakfast and the morning paper arrives just before he or she is scheduled to undergo the first diagnostic test or treatment session of the day. A child who is used to a bedtime story may have great difficulty sleeping without it.

Familiarity is most significantly embodied by people and pets in the home. An older woman may literally live for the companionship of a small granddaughter. A single person may look forward to the weekly visit of a bridge group or housekeeper. Children have the familiarity of family and playmates. The harsh restrictions regarding visiting hours, number of guests, and, most of all, the exclusion of children or pets from the presence of institutionalized patients, may be a source of sorrow in itself.

All of these examples highlight serious but often unstated problems that patients in health care facilities face—to find basic comforts that they have experienced in their homes. In fact, patients do try to retrieve a little bit of home. A remarkable sign is the contents of their rooms and bedside stands. Contents of a stand tell one as much about the patient as the contents of a small boy’s pocket does about him (Figure 6-3). Generally, the tabletop is cluttered with greeting cards, photos, or stuffed animals. In the top drawer are stamps, writing paper, religious books or objects, assorted ointments, a Swiss Army knife, a cell phone, and more! One of the authors once found a smoked herring in the back of a drawer after a roommate complained that the patient in the next bed was sneaking fish into his bland diet, and the smell was telling all.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree