Chapter 8 Reorienting health services

Overview

Many agencies, services and practitioners contribute to the promotion of health and this chapter outlines the role of these stakeholders and different occupational groups. A reorientation of health services towards prevention was one of the key action areas of the Ottawa Charter (World Health Organization 1986), yet it is the least successfully applied. Health promotion poses several ambitious challenges for the health care sector: to extend the core business of health services from clinical outcomes to quality of life; to extend the focus from patients and relatives to staff and the wider community; and to integrate prevention into care and cure practices. To do so can only be achieved through organizational and funding changes. This chapter discusses these challenges, the practitioners and agencies involved in promoting health, and how their contribution to health promotion can be mainstreamed and validated. The provision of health and social care services differs widely from country to country, and this chapter focuses on the UK experience.

Introduction

Historically the cure and treatment of illness have taken precedence over the prevention of ill health, or the promotion of positive health in the organization. Most people thinking of health services think of hospitals and family doctors, a focus on treatment, developments in surgery and new techniques and more effective medicines. There is widespread acceptance that prevention is better than cure and it is the only rational way forward for public health. Yet a recent review claims that 1.5 million pounds sterling is spent on prevention and health promotion in the UK each year, which is the sum spent on the National Health Service (NHS) in a day and a half (Wanless et al 2007). Part of the reluctance to invest in prevention is because the benefits accrue over time and so with limited resources and a pressure to demonstrate results, the focus of health services becomes skewed towards care.

Whilst the contribution of health services to longevity is clear, as we saw in Chapter 2 many factors unconnected with health services have a profound impact on health. For many health promotion practitioners, the contribution of health care services in addressing the determinants of health is marginal (Wise & Nutbeam 2007). However health services do have a unique and significant contribution to make towards population health. This chapter argues that health services, defined as ‘all the activities whose primary purpose is to promote, restore, or maintain health’ (World Health Organization 2000) are critically important in progressing health and human development.

The Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (World Health Organization 2007, p. viii) has considered the contribution of health systems to equity. In pairs, decide to be A or B and develop some examples and argument to support the statements below:

What these statements illustrate is that, whilst health services may be a trusted focal point for any society, they may inadvertently contribute to inequity. In Chapter 4 we outlined the case made for health promotion by the Ottawa Charter of 1986 which stated that health care should encompass traditional education, disease prevention and rehabilitation services but also ‘health enhancement by empowering patients, relatives and employees … enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health’. Not only would this involve ‘open[ing] channels between the health sector and broader social, political, economic and physical environmental components’, but it would also demand a ‘change of attitude and organization of health services which refocuses on the total needs of the individual as a whole person’.

Reorienting health services is the least successfully applied of the Ottawa Charter’s key action areas (Wise & Nutbeam 2007). What might be the reasons behind this? Is there a case for continued or enhanced action to reorient services?

Resistance to reorienting health services is primarily due to the organizational tradition and culture, particularly within the state-funded NHS, of providing treatment and care. This acute-care paradigm means that all too frequently health practitioners view their role as patching people up and sending them home. Prevention is seen as ‘helping people to get better by doing what is good for them’, with patient compliance as an important objective. Patients who do not take advice may be seen as demanding and, in some cases, refused treatment if they do not follow recommended behaviour change. In countries funded by social contributions, practitioners who are paid by a fee for service have little incentive for prevention and activities such as managing chronic disease or health education which are time-consuming and bring no financial reward.

Yet there is some evidence of change and a recognition of the need to move towards a national health service and away from being a sickness service (Department of Health 2005, p. 119). The focus has shifted from treatment for acute conditions to the management of chronic conditions and the maintenance of optimum health. In recent years, ‘self-management’, ‘collaborative’ care, ‘shared decision-making’ and ‘the expert patient’ have become integrated into the management of chronic lifestyle conditions such as diabetes. Our companion volume Public Health and Health Promotion: Developing Practice (Naidoo & Wills 2005) discusses these moves to involvement and participation by patients and the public in health service planning and delivery in Chapter 6.

A major incentive for the reorientation of health services is economics. Increased longevity and expectations coupled with the rising costs of health services have led to a concern with the cost-effectiveness of services. There is growing evidence of the economic case for shifting focus from treatment to health promotion. A major UK review to examine health care funding needs (Wanless 2002) concluded that the ‘fully engaged scenario’, in which people self-manage their health and the NHS embraces prevention, is the most cost-effective.

The goals of reorienting health systems are:

Promoting health in and through the health sector

The NHS is a social setting just like a school or workplace. It has its own organizational procedures, values and ethos and cultural norms. For it to embrace health (rather than the treatment of disease) as its goal requires a change in all these elements.

There are several unique characteristics of the health service setting that make it ideal for promoting health. Use of health services is universal, so that everyone at some point in their lives comes into contact with health service providers. For many more vulnerable groups, such as people with long-standing limiting illness, contact is long-term and frequent. In the UK 97% of the population is registered with a general practitioner (GP) and 70% consult their GP at least once a year. Health practitioners enjoy high levels of trust and credibility amongst the general population and thus have the ability to affect people’s knowledge, attitudes and beliefs. The NHS is the country’s largest single employer and therefore workplace initiatives may affect a significant percentage of the workforce and their families. All these factors provide good reasons for prioritizing the health services as a setting for health promotion. Chapter 16 discusses the hospital as a health-promoting setting.

Primary health care and health promotion

The 1978 Alma Ata declaration (World Health Organization 1978) defined primary care:

Primary health care (PHC) incorporates primary care, but has a broader focus through providing a comprehensive range of generalist services by multidisciplinary teams that include not only GPs and nurses but also allied health professionals and other health workers. PHC services also operate at the level of communities. The Royal College of General Practitioners (www.rcgp.org.uk) identifies the functions of the PHC team as:

Primary health care principles

The PHC approach is characterized by the following principles:

Primary health care: strategies

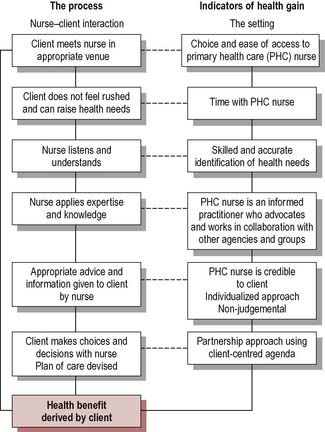

PHC strategies need to be consistent with the underlying philosophy of health promotion. In Chapter 5 we discussed various approaches to promoting health, of which education is one approach. Through education, communities and individuals gain understanding of the factors influencing their health and can work to gain control over health problems. The term empowerment is often used to describe patient education or any communication with a patient that is client-centred in its orientation. Yet empowering approaches necessitate organizational and environmental change. Figure 8.1 shows how empowerment and health gain can be built into nurse–client contacts.

Much of the health promotion practised in PHC settings is carried out by nurses. Much of this is opportunistic. A client has a consultation or is referred to a member of the PHC team and is identified as ‘at risk’. The practitioner takes the opportunity to offer advice, information or a further referral on a health-related issue. In some cases, the practitioner may start a series of brief interventions using motivational interviewing to identify the client’s readiness to change (see Chapter 9).

How many advantages and disadvantages of opportunistic health promotion can you identify?

You may have included some of the following:

The advantages of opportunistic health promotion include:

The emphasis of recent policy has been on developing more planned and proactive health promotion activities. The need for a risk assessment becomes a key skill enabling PHC practitioners to target health promotion better. For example, only a minority of those at risk of a sexually transmitted infection (STI) attend genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics, whereas the great majority of adults will access primary care in any one year. Matthews & Fletcher (2001) suggest therefore that GPs are likely to encounter patients from across the risk spectrum for STIs and should develop planned ways of raising the issue of sexual health risks with all patients.

Primary health care: service provision

Do you see any similarities in the following description of two forms of PHC?

The Peckham experiment

The Pioneer Health Centre was started in the 1930s by two doctors concerned about the health of poor people living in south London. The Health Centre tried to address health in a holistic way and incorporated a fitness club, theatre, gym, swimming pool, billiards table, children’s nursery, a cafeteria serving healthy, cheap food, a library and medical consulting rooms. For one shilling (5p) a week per family, all of the Centre’s facilities could be used. In 1938, 600 families belonged. It closed during the Second World War, reopening in 1946 when it added a nursery school, youth club, marriage advisory service, Citizen’s Advice Bureau and child guidance. It closed in 1950 because it did not fit into the structure of the emerging NHS. The Centre has been revived as Pulse Health and Leisure – a partnership between Southwark Council and Lambeth, Lewisham and Southwark health authorities funded by £3.2 million of lottery money. Its aim is ‘to provide a unique leisure, health and fitness resource that encourages local people to invest in their own health and well-being’. The new partnership thus puts the responsibility for health squarely with the individual.

Polyclinics

Polyclinics will offer not just GP services, but also ‘antenatal and postnatal care, healthy living information and services, community mental health services, community care, social care and specialist advice all in one place. They will provide the infrastructure (such as diagnostics and consulting rooms for outpatients) to allow a shift of services out of hospital settings. They will be where the majority of urgent care centres will be located. And they will provide the integrated, one-stop-shop care that we want for people with long-term conditions’ (Darzi 2007, p. 11, para. 22). The staff in each centre will include GPs, consultant specialists, nurses, dentists, opticians, therapists, emergency care practitioners, mental health workers, midwives, health visitors and social workers (Darzi 2007, p. 92, main table). The shift of much health care out of hospital settings means that in the future ‘the bulk of healthcare activity will take place in polyclinics’ (Darzi 2007, p. 107, para. 71).

Traditional models of PHC that assumed the family doctor would build up a detailed knowledge of patients over time and visit in their own homes are changing, however, and may not be relevant for transient and culturally diverse populations. Consultations in general practice in the UK tend to be short (8–9 minutes) compared to other countries and unable to address adequately the wide range of psychosocial problems experienced by disadvantaged population groups. GP’s awareness of possible referral options in the locality is also limited (Popay et al 2007), although innovative ‘social prescribing’ projects exist such as the one in Stockport, in which a GP may refer to arts, gardening schemes, learning or a self-help library.

BOX 8.1

BOX 8.1 BOX 8.2

BOX 8.2 BOX 8.3

BOX 8.3 BOX 8.4

BOX 8.4

BOX 8.5

BOX 8.5 BOX 8.6

BOX 8.6 BOX 8.7

BOX 8.7 BOX 8.8

BOX 8.8