Chapter 4 Renal physiology and the pathology of renal failure

Before any discussion of the pathology of renal failure can begin, it is important to review the following functions that normal kidneys perform (Fig. 4-1):

In addition, the kidneys have several endocrine functions, including the following:

• Production of renin, which affects sodium, fluid volume, and blood pressure

• Formation of erythropoietin, which controls red cell production in the bone marrow

A normal kidney is also a receptor site for several hormones:

• Antidiuretic hormone (ADH), produced by the pituitary, reduces the excretion of water.

• Aldosterone, produced by the adrenal cortex, promotes sodium retention and enhances secretion of potassium and hydrogen ion.

• Parathyroid hormone increases phosphorus and bicarbonate excretion and stimulates conversion of vitamin D to the active 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol vitamin D3 form.

Renal physiology

How is blood supplied to the kidneys?

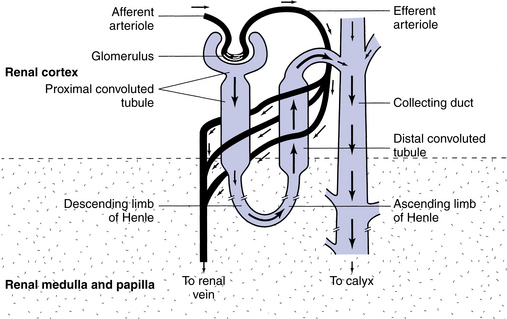

The kidneys are highly vascular organs that receive 20% to 25% of the resting cardiac output, which is greater than 1000 mL/min. Cardiac output is the volume of blood pumped per minute by each ventricle of the heart. Each kidney receives blood from a renal artery that originates from the abdominal aorta, and blood leaves the kidney through the renal vein. The renal artery branches out to form the afferent arterioles, which in turn form the glomerular capillaries of individual glomeruli. The glomerular capillaries then join to form the efferent arterioles, which in turn diffuse into peritubular capillaries and the vasa recta (Fig. 4-2).

Figure 4-2 The venous vessels of the kidney parallel the arterial vessels and are similarly named.

(From Copstead LC, Banasik JL: Pathophysiology, ed 4, St. Louis, 2010, Saunders.)

Blood flow to the kidney is dependent on hydration and cardiac output. Dehydration, blood loss, congestive heart failure, and myocardial infarction are examples of situations that would compromise blood flow to the kidney.

What is a nephron?

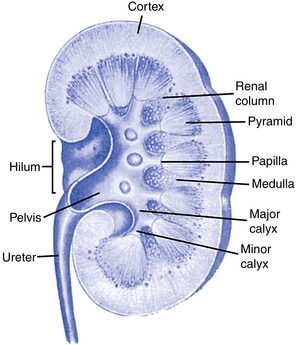

The glomerulus consists of a network of thin-walled capillaries supplied by the afferent arteriole and is closely surrounded by a pear-shaped epithelial membrane called Bowman’s capsule. The glomerulus and Bowman’s capsule combined are called the renal corpuscle. The space between the two layers of Bowman’s capsule opens into the proximal tubule, which makes a series of convolutions in the cortex of the kidney. It straightens out and then makes a U-turn, known as the loop of Henle, in the kidney medulla. It becomes convoluted again adjacent to its own glomerulus and finally joins other distal tubules to form a collecting duct to carry the freshly formed urine to the kidney pelvis (Fig. 4-3). Each kidney pelvis funnels the urine into its ureter, which connects with the urinary bladder. The urethra conveys the urine from the bladder to the exterior.

What happens to the filtrate as it moves through the tubules?

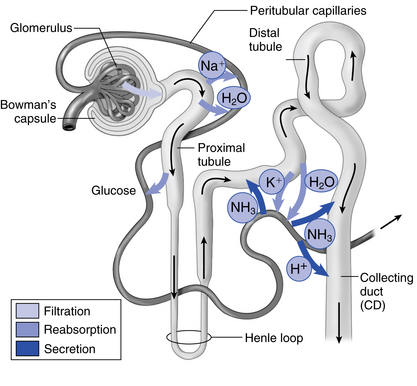

The main function of the tubules is reabsorption and secretion. Tubular reabsorption is the process of the filtrate moving back into the blood of the peritubular capillaries or vasa recta (Fig. 4-4). This process is very selective and depends on the body’s needs at the time. Materials that are reabsorbed into the bloodstream are such ions as sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, and calcium.

Figure 4-4 Path of filtrate as it moves through different parts of a nephron.

(From Thibodeau GA, Patton KT: Anatomy & physiology, ed 7, St. Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

Renal failure

What happens in kidney failure?

The normal urinary system maintains fluid volumes and the levels of many chemicals in the body. When the urinary system is not working properly, normal blood composition is disrupted and the patient will experience symptoms. Renal failure may be acute or chronic. In both types of renal failure there is enough loss of nephron function to upset the normal steady state of the body’s internal environment. Waste products of protein metabolism accumulate and will necessitate treatment of some kind.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree