Chapter 23 Renal complications of HIV infection

Introduction

In the early 1980s, a unique form of kidney disease was described among HIV-infected patients [1, 2]. Patients usually presented with significant proteinuria and rapid progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [2]. When initially described, this renal failure was attributed to heroin nephropathy, as it clinically appeared similar. As clinicians continued to see renal disease associated with HIV infection, the existence of a distinct disease called HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) was debated. As more patients with HIV infection without a history of heroin use were noted to have renal disease, HIVAN was established as a unique entity [2]. From a once rare complication of HIV infection, HIVAN has emerged as the most common cause of ESRD in HIV-infected patients [3]. In addition, as patients with HIV/AIDS are surviving longer, the prevalence of HIV-infected patients with chronic kidney disease continues to rise [4]. With up to 33 million people infected with HIV/AIDS worldwide and a prevalence of renal disease in HIV-infected black patients of 3.5–12%, up to 4 million people worldwide may be affected by HIV-related kidney disease [2, 5]. This chapter will review the epidemiology and clinical course of HIV-related renal disease using US, European, and African studies to compare results based on regions of the world. Such a comparison requires initial insight into methods and infrastructure for delivery of healthcare within regions to provide a framework for the understanding of study comparisons.

Epidemiology

One of the first clinical reports of HIVAN occurred in 1984 in the USA [1]. Not surprisingly, the initial description engendered a debate that was focused mainly on whether this was a different entity from heroin nephropathy. As children and patients without a history of heroin use were identified with renal disease and the disease became better defined histologically, the term HIVAN emerged to describe the combination of clinical and histological findings. In the early era of HIV, patients with HIVAN were diagnosed late in the course of HIV infection, usually after they had been diagnosed with AIDS. Predictably, renal survival for those diagnosed with HIVAN was 1–4 months without therapy [1, 2, 6, 7]. With the advent of potent antiretroviral therapy (ART) and the decline in mortality from AIDS, kidney diseases have become major contributors to HIV morbidity and mortality [8].

While no data on global prevalence exist, HIVAN is likely to have the highest prevalence in Africa. According to the 2009 report on the global AIDS epidemic, almost 33 million people are living with AIDS in the world [5]. Within sub-Saharan Africa alone, nearly 22.5 million people are currently infected. In the USA, the prevalence of renal disease has been noted to be between 3.5 and 12% in HIV-infected African Americans [2, 9]. If one assumes a similar prevalence among persons of African descent, then up to 2.7 million patients may have renal disease in sub-Saharan Africa alone. Any estimate of prevalence, however, needs to account for the different mortality rates among HIV-infected patients and its variation by country. Without having an exact estimate, the prevalence of renal disease could be hypothesized to be quite high. One report in 2003 in the Nigerian Journal of Medicine assessing the prevalence of renal disease in consecutive patients with AIDS seen in the infection unit suggested that these estimates are conservative. Of 79 patients with AIDS, renal disease was present in 51.8% (41 patients) as compared with 12.2% (7 patients) of non-HIV-infected controls. Of these 79 patients, 19% (n = 15) had azotemia, 25% had proteinuria alone, and 7.6% had both proteinuria and azotemia [10].

The current leading cause of death from AIDS worldwide is infection; but as ART becomes more available and survival is prolonged, renal disease is likely to become a major secondary cause of mortality and morbidity as it has in the USA. As the mortality rate from AIDS declined in the early 1990s, the number of black patients living with HIV increased significantly. As a result, this at-risk group lived longer, and HIVAN became one of the most rapidly growing causes of end-stage renal disease in the USA [3].

Racial distribution of HIVAN

As demonstrated by US and European epidemiologic and pathologic data, HIVAN has an overwhelmingly higher prevalence in HIV-infected patients of African descent than in Caucasians [9, 11–15]. With the emergence of HIV throughout the world in the 1980s, a change in the pathologic findings in African patients with nephrotic syndrome was described. A study from Zaire in 1993 reported the pathologic findings of 92 patients with documented nephrotic syndrome systematically biopsied between 1986 and 1989. A total of 41% of these patients were found to have focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), a sevenfold increase from previous prevalence rates of only 6%. The investigators were uncertain as to the cause of the increase in FSGS but proposed that AIDS might be responsible [16]. This study cannot assess the predisposition of blacks to HIVAN but does suggest that HIVAN has become an increasing health problem in this population. Early in the HIV epidemic, epidemiologic data from the USA and Europe found that HIVAN was diagnosed primarily in areas with large populations of HIV-infected black patients [14]. Two series from France and London have reported that 97/102 and 17/17 of patients diagnosed with HIVAN were black, respectively [17, 18].

In contrast to the high rate of HIVAN in predominantly black-populated regions, Caucasians are noted to have a much lower prevalence of classic HIVAN. A postmortem analysis of 239 consecutive Swiss patients who died from AIDS between 1981 and 1989 demonstrated pathologic renal findings in 43% of patients, with HIVAN in only 1.7% (4/239) of the patients [13]. Given that 95% of the patients were Caucasians, this study emphasizes the low prevalence of classic HIVAN in Caucasians.

Another study reviewed the pathologic features of 120 consecutively autopsied HIV-infected Caucasian patients in Italy. Of these patients, 68% had pathologic renal changes, and none of the renal specimens had classic HIVAN. The most common pathologic abnormality was immune-mediated glomerular diseases (25 patients) and tubulointerstitial lesions (19 patients) [15]. A similar study of 26 Caucasian patients in northern Italy with HIV who underwent renal biopsy failed to reveal any lesions of HIVAN. The majority of diagnoses were immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis [11]. While patients of African descent are at the highest risk for HIVAN, other ethnic groups have renal disease related to other pathologic entities.

Patterns of renal disease in Africa

There is a large variation in the patterns of renal diseases reported in different geographic regions of Africa. Unfortunately, accurate and comprehensive statistics are not available [19]. For example, a single available study of 368 patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Nigeria demonstrated that 62% had an undetermined etiology of renal failure [20]. The prevalence of CKD in sub-Saharan Africa is not known. Data from the South African Dialysis and Transplant registry regarding etiologies of ESRD reflect only patients selected for dialysis. As only patients eligible for transplantation are offered dialysis, and few patients with diabetic ESRD are offered dialysis or transplantation due to co-morbid conditions, the available data are unlikely to reflect the spectrum of renal diseases in the population as a whole.

In North Africa, the incidence of renal disease appears to be much higher than in the USA, but the prevalence is lower due to higher mortality and fewer available treatment options [21]. The reported annual incidence of ESRD ranges between 34 and 200 patients per million population (pmp), and the respective prevalence ranges from 30 to 430 patients pmp. Despite the high mortality from ESRD, the prevalence of CKD appears to be increasing. The principal causes of CKD are interstitial nephritis (14–32%), glomerulonephritis (11–24%), diabetes (5–20%), and nephrosclerosis (5–31%). Trends in Egypt suggest an increasing prevalence of interstitial nephropathies and diabetes [14]. FSGS is reported in 23–34% of the glomerulonephritides (GN) and is mostly clustered in black patients [21].

Overall, glomerular disease appears to be more prevalent and more severe in Africa than in Western countries. It has been estimated that between 0.2 and 2.4% of medical admissions in tropical countries are due to renal disease (0.5% Zimbabwe; 0.2% Kwa Zulu Natal, South Africa; 2.0% in Uganda; and 2.4% Nigeria) [22]. It has been observed that the majority of these admissions are related to glomerulonephritis, which responds poorly to treatment and progresses to ESRD. In addition, glomerulonephritis in South Africa is more frequent in blacks and less frequent in Indians and Caucasians. This is a similar pattern to the distribution of HIVAN. Given the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS in South Africa, it can be postulated that some of these renal disorders may be caused by HIVAN or other HIV-related renal diseases.

Natural History

Among patients with HIVAN, severe proteinuria (often in the nephrotic range >3 g/day) with progression to ESRD within 1–4 months of diagnosis was initially described [1, 2, 6, 7, 23]. Subsequent data in the setting of monotherapy with zidovudine and ART suggest a much slower progression [23–25]. While early reports suggested that HIVAN was a late manifestation of AIDS, occurring when CD4 counts were well below 200 copies/mL, subsequent data suggest that a lower CD4 count may be associated with a faster progression and greater likelihood of biopsy [17, 24]. A case report of HIVAN demonstrates its presence as early as the time of acute HIV seroconversion [26].

Pathogenesis

Early in the description of HIVAN, it was uncertain whether HIV caused injury through a direct effect on renal cells or an indirect effect from immune dysregulation. Studies by Bruggeman and co-workers using a murine model of HIVAN demonstrated that HIV-1 expression in renal epithelial cells is necessary for the development of the HIVAN phenotype [27]. They went on to demonstrate that both tubular and glomerular epithelial cells are infected by HIV in patients with HIVAN [28]. Furthermore, Marras and co-workers demonstrated that the renal tubular epithelial cells support viral replication and subsequent divergence, and act as a separate compartment from blood [29]. According to a study by Winston and co-workers, renal parenchymal cells can serve as a reservoir for HIV, and the presence of the virus can persist in glomerular and tubular epithelial cells despite ART [30].

The mechanisms by which HIV gains entry into epithelial cells remain unclear. The major co-receptors for HIV-1 have not been detected using immunocytochemistry, but more sensitive methods including PCR suggest that CD4 and CXCR4 can be detected in cultured renal epithelial cells [31]. The data are less clear for the other co-receptors. Whether the receptors are in sufficiently high density or functional enough to mediate entry into the cell also remains unknown [31].

The observation that HIV DNA has been found in glomeruli of HIV-infected patients without HIVAN suggests that some additional factor (such as a genetic predisposition) may be required [32]. The pathologic findings of collapsing focal glomerulosclerosis combined with tubular microcystic disease have been thought to be specific to HIVAN. However, a recent report of collapsing GN in seven HIV-uninfected Caucasian patients who were treated with high-dose pamidronate suggests that other environmental agents can also induce collapse [33]. Thus, Caucasian patients can develop a collapsing phenotype, but the mechanism appears to be different from those observed in response to HIV infection in blacks.

The racial predilection for HIVAN in blacks strongly suggests that genetic factors play an important role in the pathogenesis of HIVAN. In support of this, Gharavi and co-workers assessed the influence of genetic background on the development or progression of HIVAN by crossing the HIVAN transgenic mouse with mice of different genetic backgrounds [34]. These investigators found that the HIVAN phenotype varied from severe renal disease to no renal disease based on the background strain of the mice. In addition, genome-wide analysis of linkage in 185 heterozygous transgenic backcross mice identified a locus on chromosome 3A1-3, HIVAN1, which showed highly significant linkage to renal disease. This locus, HIVAN1, is syntenic to human chromosome 3q25-27, which is an interval showing suggestive evidence of linkage to various nephropathies [34]. More recent investigations have identified 2 genomic loci that regulate podocyte gene expression and which confer an increased susceptibility in mice to HIVAN [35].

Pathology

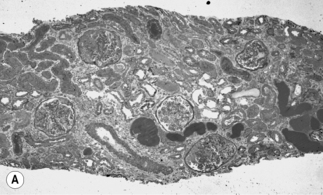

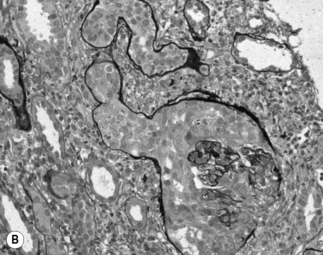

HIV-associated nephropathy has pathologic findings similar to idiopathic and heroin-related FSGS; however, there are several unique findings suggestive of HIV infection [12]. First, in HIVAN there is a tendency for the entire glomerular tuft to sclerose and collapse rather than finding only a segmental glomerular lesion (Fig. 23.1). In the tubules, there is often severe injury with proliferative microcyst formation and tubular degeneration. The tubular disease is characterized by the development of tubular dilation accompanied by flattening and atrophy of the tubular epithelial cells. Electron microscopy can reveal the presence of numerous tubuloreticular structures in the glomerular endothelial cells. The tubuloreticular inclusions are composed of ribonucleoprotein and membrane structures; their synthesis is stimulated by α-interferon. The only other disorder in which these structures are prominently seen is lupus nephritis, which is also associated with chronically high levels of circulating α-interferon. The finding of tubuloreticular inclusion had been noted to be a common pathologic abnormality in the pre-ART era; however, this pathologic abnormality is now found less frequently. This is potentially related to the advent of effective ART, resulting in reduced levels of plasma interferon [12, 36]. In HIV-infected patients with kidney disease, several different glomerular syndromes have been described (Box 23.1). The most common pathologic finding is HIVAN. In the USA, the second most common pathologic findings are membranoproliferative GN (often with HCV coinfection) or mesangioproliferative GN, followed by immune complex GN, membranous, and IgA nephropathy [12, 24]. Less commonly, HIV-infected patients have been found to have thrombotic microangiopathy, minimal change disease, and amyloidosis [24, 37]. This is in comparison to patients seen in Baragwanath, South Africa. Among 99 HIV-infected patients, 27% had classic HIVAN; 21% had immune complex rich “lupus-like” disease; 41% had other GN including 13% membranous, 8% post-infectious GN, 5% IgA nephropathy, and 6% mesangioproliferative GN, and 9% other nonspecified GN; 3% had tubulointerstitial nephritis; 3% had acute tubular necrosis; and 4% had other [38]. However, among hospitalized HIV-infected patients with acute renal failure, the most common diagnosis is acute tubular necrosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree