CHAPTER 9 Rehabilitation for the individual and family

When you have completed this chapter you will be able to:

INTRODUCTION

Following an episode of injury or illness, many persons embark on a rehabilitation journey, an ‘individual, active and dynamic process’ (Barnes & Ward, 2000, p. 6) aimed at regaining control over their bodies and their lives (Ozer, 1999). Because of the emotional and sometimes cognitive assault, a person may not become aware of this intensely personal journey until they realise that their impairments associated with the injury or illness are not going away. Furthermore, each person’s journey is unique in that the experience of injury or illness is assigned personal significance in accordance with the individual’s context and becomes part of the person’s biography (Frank, 1991). Family members, friends and colleagues also embark on a journey of their own as they seek to make sense of what has happened and integrate this into their lives.

For nurses, however, rehabilitation begins at the patient’s first point of contact and informs all decision making thereafter. Rehabilitation requires all healthcare professionals to possess, and act upon, an awareness of how what does, and does not, happen today affects the patient’s desired tomorrow (Plaisted, 1978). As such, rehabilitation is more than a series of intermittent interventions done to patients by health professionals (Pryor, 2005a). It is a continuous process that:

REHABILITATION AS AN INTERVENTION

Rehabilitation was initially practised on a large scale during World War II to get injured servicemen back to the field of combat (Smith, 2005). Since then, awareness of the benefits of rehabilitation as a service type has grown and as a consequence these services are accessed by persons experiencing limitations associated with a wide range of illnesses and injuries as well as limitations associated with the ageing process (Simmonds & Stevermuer, 2007).

Associated with this increased awareness has been debate about the nature and effectiveness of rehabilitation services. Rehabilitation has long been described as a ‘black box’, because of the multiplicity of levels of interventions (Whyte & Hart, 2003) and the many interactions between them that make rehabilitation less than an exact science. At the macro level, the model of teamwork affects patient outcomes (Stroke Unit Trialists’ Collaboration, 2002). At the micro level, teaching patients the multiple swallow technique influences patient outcomes (Halper et al, 1999).

Commentators such as Nolan, Booth and Nolan (1997) question rehabilitation’s claims of holism, noting the strong physical bias in the services provided. They argue that rehabilitation services need to focus more on the biographies of service users. Research involving service users can provide insights into what is valued by the recipients of rehabilitation services and in so doing assist service providers to focus more on their personal biographies.

Cott (2004) conducted one such study that provides guidance for ensuring that rehabilitation service delivery is client-centred. Rehabilitation clients in her study valued rehabilitation services that were characterised by:

In this context, the terms functioning and disability are defined in the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (WHO, 2001).

INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF FUNCTIONING, DISABILITY AND HEALTH

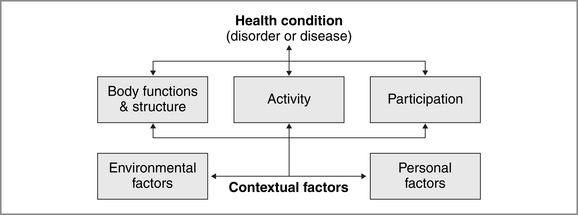

The ICF is a biopsychosocial model of disability (WHO, 2002). The ICF highlights how functioning and disability at the person level are created through the dynamic interaction between the person’s health conditions and contextual factors (see Figure 9.1).

The ICF ‘is about all people‘ (WHO, 2001, p. 7, italics original). A patient’s functioning ‘is seen as associated with, and not merely a consequence of, a health condition’ (Stucki et al, 2005, p. 349). Functioning is ‘an umbrella term for body functions, body structures, activities and participation’ (WHO, 2001, pp. 212–13). Disability is ‘an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitation and participation restrictions’ (WHO, 2001, p. 213). The components of IFC are defined in Box 9.1.

BOX 9.1 Components of ICF.

Source: WHO (2001, pp. 10, 17)

The ICF is widely advocated as a framework for acute care (Ewert et al, 2005; Grill et al, 2005; Grill et al, 2005) and post-acute rehabilitation (Boldt et al, 2005; Gravell & Johnson, 2002; Stucki et al, 2005; Wade, 2005). It facilitates the selection of rehabilitation interventions that address the full impact of a health condition on a person’s life (Kearney & Pryor, 2004).

That is, rehabilitation interventions target:

This supports the move away from an impairment-oriented approach to a functional or task-oriented approach (Wade & deJong, 2000). While ICF is a useful framework for rehabilitation, the use of goals and teamwork are critical elements in the delivery of effective rehabilitation services. The ICF facilitates teamwork by providing a common language for all disciplines (WHO, 2001).

THE USE OF GOALS

The use of goals, a hallmark of rehabilitation, facilitates patient engagement in the activities of rehabilitation and patient self-determination. Goal setting is widely supported as a pragmatic approach that fits with the problem-solving and educational processes of rehabilitation (Wade (1999)). It identifies what is important to a patient and provides the rationale for the actions of healthcare professionals. The goal of most patients is to return to their pre-injury or pre-illness life (Hafsteindottir & Grypdonck, 1997).

In relation to ICF, pre-injury or pre-illness life is often understood in terms of a person’s participation in meaningful life situations (Cicerone, 2004), for example parent, book lover, chess player or house builder. To facilitate the setting of participation goals Wade (1999) advocates the use of the ‘Life Goals Questionnaire’, on which a patient rates the importance of various aspects of their life. The findings of a study by Leidy & Haase (1999) support this approach. Persons living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, who faced the ongoing challenge of preserving their integrity, strived for ‘a sense of effectiveness or “being able” and of connectedness or “being with” [others]’ (p. 67).

Re-establishment of a ‘person’s sense of control over his or her body and life’ (Ozer, 1999, p. 43) is an essential first step in rehabilitation. As Faull and Hills (2006) note ‘the development of a resilient, intrinsic, spiritually based self’ is central to rehabilitation outcomes. Effective goal setting can assist in this process. Firstly, goals can help patients to move from pre-contemplation to action (van den Broek, 2005). Secondly, goals can be a powerful mechanism for enhancing patient ownership of, and engagement in, their rehabilitation (Levak et al, 2006). Thirdly, goals are the reference point for evaluating rehabilitation outcomes (McGrath & Adams, 1999).

The conversion of a person’s long-term participation goals into short-term goals that healthcare professionals can contribute to requires negotiation. In this process, education about the purpose and nature of goals in relation to rehabilitation is an essential first step. Demystifying the goal-setting process enables patients to re-establish decisional autonomy over their situation (Cardo et al, 2002). Mutual goal-setting should also ensure that the needs of both service users and service providers are best served, rather than rehabilitation being viewed as ‘a product to be dispensed’ (Stewart & Bhagwanjee, 1999, p. 339) ‘by one party to another’ (Clapton & Kendall, 2002, p. 990).

Short-term goals are most useful when articulated as S(specific) M(measurable) A(achievable) R(relevant) T(time-limited) goals. The relevance of SMART goals is highlighted by Hill 1999, p. 839), who herself has experienced traumatic brain injury. She notes that rehabilitation needs to assist some injured persons to ‘re-orient or rebuild their life using a new set of “maps” with which to navigate life’ (p. 839). SMART goals can contribute to the creation of these new maps.

NURSING AND REHABILITATION

Rehabilitation is central to nursing practice across the continuum of care, regardless of the patient’s age, diagnosis or setting (Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses’ Association, 2003; Pryor, 2002). The overarching goal of rehabilitation, namely maximising human potential, is synonymous with the goal of nursing. As Hickey (2003, p. 256) notes, the ‘principles of rehabilitation are an integral component of independent nursing practice’. Rehabilitation is not the exclusive domain of allied health.

Kirkevold (1997) description of four nursing functions is one way to understand nursing’s rehabilitation role. These functions, while derived from a Norwegian study of stroke nursing, are relevant to all types of rehabilitation (see Table 9.1).

Table 9.1 Kirkevold’s four nursing functions

| Interpretive function | Nurses help patients and families make sense of what has happened to them, what is happening to them and what may happen in the future. |

| Consoling function | Nurses develop trusting relationships with patients and family members and provide emotional support. |

| Conserving function | Nurses are involved in maintaining normal bodily functions with a heavy emphasis on prevention and physical protection. |

| Integrative function | Nurses help patients integrate new learning, in relation to their activities of daily living, into their daily lives. |

The findings of Australian studies of nursing and rehabilitation complement Kirkevold’s work. Four particular aspects of this body of research are of relevance to the practice of all nurses. Firstly, adopting a rehabilitative approach requires nurses to ‘focus on a person’s ability in order to see possibilities rather than focusing on disabilities’ and to adopt ‘a wellness model of care’ (Pryor & Smith, 2002, p. 253). Secondly, viewing ‘every nurse–patient interaction as a teaching/learning opportunity’ (Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses’ Association, 2003, p. 11; Pryor & Smith, 2002, p. 253) ensures nurses assess patient readiness, ability and potential to be coached to self-care. This often starts with teaching patients about rehabilitation and about how the rehabilitation roles of patients and nurses differ from their acute care roles (Pryor, 2005a).

Thirdly, like Kirkevold (1997) who reports that nurses create an atmosphere of positivity and optimism for each client, Pryor (2000) refers to a ‘rehabilitative milieu’ that is contributed to by all people and activities on the unit. In a study of five inpatient rehabilitation units, Pryor, 2005a found that nurses allowing time for patients to work at their own pace, keeping patients’ spirits up by creating a light-hearted atmosphere, protecting patients from embarrassment and making hospitalisation more home-like to be important nursing contributions to the creation of this unique rehabilitation ward atmosphere. In so doing, nurses foster self-determination, the ultimate aim being for patients to regain control over their own lives.

Fourthly, coordination of each individual patient’s rehabilitation is a nursing responsibility (Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses’ Association, 2003). However, while a purposeful sample of nurses with rehabilitation expertise reported this to be the case (Pryor & Smith, 2002), effective coordination of patient rehabilitation by registered nurses was not evident in data collected from a sample of 53 nurses (Pryor, 2005a). The introduction of a patient care coordinator was evaluated positively in another Australian study (Pryor, 2003), as have been similar initiatives elsewhere (e.g. Burton, 2000).

Three knowledge types, identified by Liaschenko and Fisher (1999) and discussed by Stevenson, Grieves and Stein-Parbury (2004), are central to the effectiveness of nursing in supporting patients on their rehabilitation journey:

The following factors are necessary if nurses are to get to know their patients: ‘(i) mutual trust and rapport; (ii) a positive nurse–patient attitude; (iii) sustained nurse–patient contact; and (iv) meaningful interaction’ (Henderson, 1997, p. 112). Relationships built upon these factors facilitate the negotiation of mutually agreed goals and the coaching of patients to take that next step on their journey towards self-care and independence.

In the remainder of this chapter, rehabilitation as a personal journey following injury or illness and as an intervention is illuminated through the presentation of Benjamin’s story.

BRAIN INJURY—WHAT IS IT?

The brain is a complex organ that controls everything we do. ‘Acquired brain injury (ABI) is a collective term used to describe brain injury as a result of traumatic or non traumatic events’ (O’Reilly & Pryor, 2002, p. 34). It is ‘injury to the brain which results in deterioration in cognitive, physical, emotional or independent functioning’ (Department of Human Services and Health, 1994, p. 29). Acquired brain injury is commonly classified as traumatic (TBI) or non-traumatic. A blow to the head causes TBI. In the case of a motor vehicle accident, the head moving forwards and/or backwards too quickly injures the brain. Non-traumatic brain injury is caused by lack of oxygen to the brain as a result of an internal incident such as infection or stroke.

ABI can affect a person’s ability to communicate, to process information they have seen or heard or to behave in an appropriate or socially acceptable way. It can cause impairments to bodily functions, such as walking, bladder and bowel function or temperature control. It can also affect emotions and memory. These are just some of the difficulties a person who has sustained a brain injury may experience. These are significant in their own right, but it is the combination of these changes that can make it a challenge for a brain-injured person to return to their pre-injury life (Brain Injury Association of Queensland, 2006; O’Reilly & Pryor, 2002).

An ICF core set for patients with neurological conditions in acute hospitals was developed by 21 experts to provide all healthcare professionals ‘with a clinical framework to comprehensively assess patients in acute hospitals’ (Ewert et al, 2005, p. 367). This set includes impairments of body structures and functions, activity limitations and/or participation restrictions as well as environmental factors that interact with neurological conditions and contribute to a person’s experience of disability. Benjamin’s neurological impairments are presented in Table 9.2. However, as Rees, 2005 highlights, a person experiencing disability also has many abilities. Therefore, ‘nurturing preserved abilities’ is also a primary focus of rehabilitation (Rees, 2005, p. 14).

Table 9.2 Benjamin’s neurological impairments

| Diffuse axonal brain injury | Acceleration/deceleration injury caused by shearing of cerebral matter (Albano et al, 2005) |

| Bilateral frontal brain haemorrhages | Acceleration/deceleration injury resulting in bruising of the brain’s surface, with symptoms usually becoming apparent within the first 24 hours after the initial injury (Hickey 2003) |

| Left frontal cortical contusions | Resulting from ‘compression of the brain against the skull at the point of impact [coup injury] and a rebound effect where there is compression of brain tissue 180 degrees from the point of impact [countrecoup injury] also against the skull’ (Nolan, 2005, p. 190) |

| Urinary incontinence | Due to frontal lobe brain injury (Bardsley, 2000) |

| Musculoskeletal immobility | Due to barbiturate induced coma |

ACUTE CARE: WHERE REHABILITATION BEGINS

Life as Benjamin knew it changed as a consequence of trauma to his body. Participation in valued life situations, such as playing guitar in a band, driving his car and interacting with his family, has been interrupted. Benjamin embarks on a journey ‘from victim to patient to disabled person’ (Morse & O’Brien, 1995, p. 886). Based on a qualitative meta-analysis of the literature, Morse (1997) describes this journey as a five-stage process of responding to threats to integrity (see Table 9.3).

Table 9.3 Five stages of responding to threats to integrity

| 1 | Vigilance | ‘The first changes in the onset of acute or chronic illness bring about a dis-ease, with the individuals suspecting that something is wrong’ (p. 28). |

| 2 | Disruption: enduring to survive | ‘The major task of the critically ill is to hold on to life’ (p. 31). |

| 3 | Enduring to live: striving to regain self | ‘Once the acute crisis has been resolved, the real work derived from illness or the injury must begin’ (p. 31). |

| 4 | Suffering: striving to restore self | The person ‘begins to struggle with grief, mourning what has been lost and the altered future’ (p. 32). |

| 5 | Learning to live with the altered self | ‘The person must get to know and to trust the altered body’ (p. 33). |

Source: Morse (1997)

In all acute care settings (emergency, high dependency and the ward), nurses contribute to Benjamin’s recovery, his rehabilitation and the preservation of his integrity as a person. In terms of ICF (WHO, 2001), Benjamin has significant impairments of body structures and functions as well as activity limitations and participation restrictions.

Throughout his post-injury journey, Benjamin’s goal is to return to his pre-injury life. This goal guides the efforts of the healthcare team. In turn, members of the team, in particular nurses because they spend the most time with patients, ensure that the relationship between all the short-term goals they use to inform their interventions and interactions and Benjamin’s long-term goal are clearly explained to Benjamin and his family. This is an essential aspect of nursing’s interpretive function, as is explaining to Benjamin and his family the nature of Benjamin’s injuries and the processes and rationale for the various treatments. Understanding how the interventions of healthcare workers relate to a person’s life assists people integrate what is happening into their lives.

The consequences of injuries like Benjamin’s on families are significant. Burton and Volpe (1993) describe the impact of brain injury as reverberating throughout the entire family. Pratt and Baldry (2002, p. 291) describe this reverberation as follows:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree