INTRODUCTION

There has been a shift from custodial care to rehabilitation in a variety of contexts ranging from the care of the elderly to children’s disorders and from physical disorders to enduring mental illness. Indeed, health policy over a decade and a half ago, in the form of The Health of the Nation (Department of Health 1991a), identified rehabilitation as a key area in the strategy for health. The long-term conditions National Services Framework (NSF) (Department of Health 2005) reiterates this commitment to rehabilitation and the provision of services to meet the needs of people requiring such interventions. Rehabilitation can be seen as an area of central importance to healthcare delivery.

Various definitions of rehabilitation are available, but Wade’s (2005: 814) is comprehensive, proposing rehabilitation is:

an educational, problem-solving process that focuses on activity limitations and aims to optimize patient social participation and well being, and so reduce stress on care/family

The word ‘process’ in the above definition suggests an activity that moves forward through a series of actions aimed at achieving an identified result.

Rehabilitation is associated with the notion of recovery but the two do not mean the same thing. Rehabilitation focuses on the helping process whereas ‘recovery’ focuses on the experience of the person who is trying to overcome a particular disability. A psychologist, service user and writer, Patricia Deegan, described recovery from mental health problems in terms of regaining a sense of self and a sense of purpose ‘within and beyond the limits of the disability’ (Deegan 1988: 11). The notion of ‘recovery’ from mental illness developed from service users themselves and Deegan’s work has influenced contemporary thinking about mental health care by health care professionals and policy makers. For example, one of the Ten Essential Shared Capabilities for mental health practice (Hope 2004: 3) is ‘promoting recovery’:

Working in partnership to provide care and treatment that enables service users and carers to tackle mental health problems with hope and optimism and to work towards a valued life-style within and beyond the limits of any mental health problem.

The Chief Nursing Officer’s review of mental health nursing (Department of Health 2006: 17) similarly advocates a ‘recovery approach’ which stresses the need for optimism by nurses, where recovery does not necessarily mean a full return to previous functioning, or a cure, but rather the instillation of hope about the possibility of positive change in an individual.

Recovery is also relevant to people with physical disabilities. For example, the woman whose life has involved playing tennis, running and skiing will have to revise her sense of self as an active ‘sporty person’ if she becomes incapacitated through severe arthritis or a serious road traffic accident. However, with support and positive attitudes from healthcare professionals, the effects of an illness can be minimized so that they interfere with a person’s lifestyle as little as possible. Rehabilitation then can promote recovery. Repper & Perkins (2003) discuss the notion of recovery and rehabilitation in mental health nursing, although their ideas are transferable to other branches. They note the importance of giving hope and the importance of a supportive nurse–patient relationship. Allvin et al (2007: 557) define recovery from a postoperative perspective as:

an energy-requiring process of returning to normality and wholeness as defined by comparative standards, achieved by regaining control over physical, psychological, social and habitual functions, which results in returning to preoperative levels of independence/dependence in activities of daily living and an optimum level of psychological well-being.

This definition reminds us that recovery can be a difficult process, encompassing many aspects of a person’s life which will need to be considered by the rehabilitation nurse.

As will be discussed later in this chapter, it is suggested that the role of nurses in the process of rehabilitation is often poorly defined (Kvigne et al 2005). However, Jinks & Hope (2000) indicate nurses are the ‘glue’ within the multidisciplinary team, acting as coordinators of care and providing a holistic overview. It is argued by Low (2003) that in acting as coordinators of care, nurses fulfil one of the most central roles within the rehabilitation process. The Royal College of Nursing (2007a: 9) suggest that ‘the role of the nurse is to be there, offer personal support and practice expertise but always to enable the person to follow their own path’.

Blanche-Spelich et al (2004) propose that the process of rehabilitation knows no boundaries, being equally relevant to individuals with a range of health problems/illnesses/disabilities across all ages, ethnic and social groups. Rehabilitation activities are undertaken in a range of settings, from acute inpatient care to day and community settings. As such, rehabilitation can been seen as an aspect of every nurse’s practice and warrants close consideration.

OVERVIEW

This chapter addresses factors that influence the process of rehabilitation and recovery. Numerous terms are used to describe people who are recipients of care. In this chapter the terms patient, client and service user are used interchangeably to represent this group.

As identified above, recovery is a concept associated with rehabilitation in mental health; however, it can readily be applied to other branches of nursing. Therefore, wherever recovery is pertinent to discussions in this chapter it will be included.

Within contemporary service delivery, user and carer involvement is fundamental to successful rehabilitation programmes and you will also see this reflected throughout this chapter.

The chapter is divided into four main parts.

Subject knowledge

The first section, Subject Knowledge, develops the scope of rehabilitation. Rehabilitation is undertaken in a wide range of settings and it would be impossible to address all care groups here. However, the social, psychological and health policy aspects are common and have great relevance to all forms of rehabilitation and for this reason form a large component of this section.

Care delivery knowledge

The second section of the chapter, Care Delivery Knowledge, examines the roles of service users, carers and nurses in rehabilitation. The use of decision-making exercises and suggestions for portfolio work will help you to develop an understanding of the issues that underpin the associated nursing care.

Professional and ethical knowledge

The third section of the chapter, Professional and Ethical Knowledge, focuses on three main issues: the impact of health policy, the nurse’s role in interprofessional working and ethical issues in rehabilitation.

Personal and reflective knowledge

Finally, in Personal and Reflective Knowledge, the main points of the chapter are revisited both through the use of case studies and in providing suggestions for portfolio evidence. You may find it helpful to read one of the case studies on page 456 before you start the chapter and use it as a focus for your reflections while reading.

SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

As identified above, rehabilitation is undertaken in a wide range of settings and it would be impossible to address all care groups here. However, the social, psychological and health policy aspects are common and have great relevance to all forms of rehabilitation and for this reason form a large component of this section.

THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL CONTEXT OF REHABILITATION

The underpinning social and health policy context has great relevance to all forms of rehabilitation. Consequently it is important for nurses to first understand these issues, with the RCN (2007b) stating that an understanding of such issues is essential if the nurse is to fulfil their role in advocating for changes to care delivery and management services for patients.

Social policy relates to central and local government activities associated with the provision of services related to health, education, housing and social services, including social security and income support. It addresses questions concerning how much welfare the state should provide and how this is to be funded. Health policy, as one aspect of this, is of particular interest to those involved in the delivery of care. Scott (2001) argues that the overlapping of health policy with nursing policy requires nurses to have an understanding of how one impacts on the other and the implication of this for care delivery.

Developed countries are viewed as having a mixed economy of welfare made up of:

• state sector

• private sector

• voluntary sector

• informal carers.

Recently in the UK there has been an emphasis on involving patients and the public in developing health and social services and delivering. The way in which this involvement has developed can be understood from the prevailing political and social climate. Barnes et al (2000) identify three models of user involvement, which show different emphases over time. These are, the ‘consumerist’ approaches during the 1980s and early 1990s; the ‘democratic model’ in the mid-1990s and the ‘stakeholder model’, representing approaches in the early 21st century.

The consumerist model

In the political context of the 1980s and 1990s the emphasis on introducing an internal market (Department of Health 1989) in health care led to the view that patients should be viewed as customers or consumers of health services. The Conservative governments between 1979 and 1997 emphasized the responsibility of individuals to maintain their own health. Indeed, the first reference to the public as customers of health services appeared in Patients First (Department of Health and Social Security 1979). This consumerist approach was reflected by a change in the roles of service providers who were concerned to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of services to patients.

The early 1990s saw a number of policies that developed the consumerist model. For example, the NHS and Community Care Act (Department of Health 1990) required local authorities to consult with service users and carers, then, in 1991, the Patients’ Charter (Department of Health 1991b) established a framework for patient entitlements. The involvement of the ‘consumers’ was acknowledged in Local Voices (Department of Health 1992), which recommended community involvement to help in the planning and monitoring of services in the NHS.

The democratic model

In contrast to the consumerist approach, the democratic model is associated with service users who challenged the inequalities in power between service providers and consumers (Beresford & Croft 1993). This can be most clearly seen in the rise of the user movement in the UK when groups of mental health service users were established to argue against what they saw as an unfair distribution of power in favour of the professions. The democratic model is about more than having a voice in health and social care services. It is concerned with how citizens are treated and regarded, based around a belief that everyone should have a greater say and more control over state funded institutions which influence the lives of the population.

Closely associated with the democratic model is the notion of ‘empowerment’. Empowerment has been described as a process and an outcome (Ryles 1999). As a process, the empowerment of patients by health professionals is considered possible if professionals relinquish their own power, but as Masterson & Owen (2006) argue, social change is needed to allow new-found power to be exerted. So, at the level of care delivery empowerment can be understood as the nurse maximizing the patient’s independence and minimizing dependency. At a political–social level, it can be seen through policies which enable individuals to influence the development and delivery of healthcare services. When considering the outcomes of empowerment, it appears that the concept is more easily understood by its absence. For example, Gibson (1991) identified powerlessness, helplessness, hopelessness, oppression, loss of control over one’s life and dependency as indications of a lack of empowerment.

The stakeholder model

With political changes from the late 1990s during the period of the New Labour government, Barnes et al (2000) argue that consumerism and empowerment have evolved into the stakeholder model. This position suggests that public services are best planned and delivered when the views of key parties, including those of service users, professionals, the general public and government, are actively sought and taken into account. The idea of ‘partnership’ is emphasized rather than the empowerment of one group. Under a stakeholder model, service users’ and carers’ views and knowledge are accepted as equally important to those of other stakeholders and they are therefore regarded as ‘partners’. So the goal of this model is to ensure that users’ and carers’ voices are heard and their views have influence. Inequalities in power between the different parties are accepted as the reality, rather than being open to challenge. In the stakeholder model, service users and carers will usually be invited to participate on the terms set out by policy makers and professionals.

The stakeholder model has been espoused in a series of Labour government reports since 1997, which have emphasized the need to involve patients and the public in decision making about health and social care (for example Department of Health, 1997, Department of Health, 2000 and Department of Health, 2001c). These culminated in the Health and Social Care Act (Great Britain 2001), which placed a duty in law on the NHS to make arrangements to involve and consult patients and the public in decisions about health services and can be seen in various consultation groups such as Patient Advice and Liaison Services (PALS), Local Involvement Networks (LINks) and Patient and Public Involvement Forums (PPI Forums).

See Evolve 19.1 for more information on patient and public involvement.

• Be familiar with government legislation and recommendations on public involvement in strategic decisions on health care.

• Be familiar with government legislation and recommendations on patients’ rights to involvement in their own care in partnership with health professionals.

SOCIAL ROLES

The social and political context explains how a society views rehabilitation. To explore what it actually means for individuals requires an understanding of how individuals interact within society. It is suggested that individuals and society interact through taking various social roles. This provides a sense of purpose and belonging for all individuals within society and allows the individual to develop a concept of self. A loss of social role can occur following illness or disability or as a result of the often prolonged process of rehabilitation. Therefore as Wade (2005) proposes, a significant aspect of rehabilitation is enabling individuals to maintain and/or resume as far as possible their social roles and is central to planning rehabilitation programmes.

Social roles are associated with the individual’s status within his or her society. Status encompasses such things as:

• gender (e.g. male or female)

• occupation (e.g. nurse, farm worker, tailor)

• family relationships (e.g. daughter, brother, parent).

Status is also culturally defined and may be either:

• fixed or ascribed (e.g. gender or ethnicity), or

• achieved (e.g. marital status or class).

For each status there are identifiable expected and acceptable ways of behaving. These are known as ‘norms’. The group of norms attached to a particular status is a ‘role’. Therefore each status is accompanied by a role, which shapes and directs social behaviour. Individuals then perform this role in relation to one another (Table 19.1). This enables individuals to interact with each other, predict how others will behave and have a clear idea of what is expected in terms of their own role. For example, in the interaction between nurse and client, each knows what is expected of them and how the other should respond. Both nurse and client can then concentrate on the situation they are in without being inhibited by other aspects of their lives.

| Status | Nurse |

|---|---|

| Norms | Knowledge of illness Cares for people Gentle and kind |

| Role | Wears a uniform Practical Busy |

When someone becomes ill they may not be able to fulfil their normal roles and this affects their perceived status and self-esteem. For example, if a woman experiences a stroke that affects her ability to do domestic activities, she may feel that this affects her role as a provider of care for her husband. This may have an impact on the way the husband and wife interact and their expectations of each other.

The above discussion presents social roles and obligations as clearly identified and explicit concepts. However, roles can be seen as fluid and changeable.

An alternative way of thinking about roles is seeing them as having generally defined aspects but certain elements within them being subject to individual negotiation. For example it can be said that there is no script as to how a student nurse should behave; rather this is negotiated between students and their teachers, placement supervisors and clients. This negotiation occurs in relation to an individual’s understanding of the role and their beliefs.

Men are perceived as being socialized into a particular gender role and as such this has implications for the ways in which they view health and their response to disease. White & Johnson (2005) conducted in-depth interviews with men admitted to hospital with chest pain. They found that all the men delayed seeking help and tried to explain their symptoms as common everyday problems such as wind or heartburn. It is suggested this is in part due to the ‘macho’ ideal present within Western society and the socialization of men into roles that promote the image of men as strong, productive, fit and healthy. Delaying initial treatment of acute chest pain can have serious implications for treatment and outcomes and the eventual impact on men’s general well-being.

The sick role

Parsons (1951) argued that in times of illness, Western societies allow individuals to take a sick role. This means that individuals are not expected to contribute economically to society during the time of their sickness and are not subject to any moral blame for their illness. However, they are expected to comply with treatment and do all in their power to work with the professionals to aid their recovery (see Table 19.2 for rights and obligations of the sick role). The social exchange in Parsons’ theory means that compliance with treatment and trying to get well again allows the sufferer to experience a form of no fault–no blame agreement in the eyes of society.

| Right or obligation | Provisos |

|---|---|

| Two rights | |

| The sick person is exempt from performing his or her usual social role | This exemption is relative to the severity of the illness It must be legitimized by others – often the doctor is the legitimizing agent |

| The sick person is not responsible for his or her illness | The person is not expected to ‘pull themselves together’ As he or she is exempt from responsibility, there is an expectation of ‘being taken care of’ |

| Two obligations | |

| The sick person must get better as soon as possible | Being ill is unacceptable and the person must be motivated to get well |

| The sick person must seek medical advice and comply with the treatment prescribed | Help must be sought from a competent and acceptable source in relation to the severity of the illness |

The implication of sick role theory for individuals is that they are expected to accept, rather than to challenge care decisions made by professionals which results in an imbalance in power between professional experts and patients. Unlike the stakeholder model mentioned earlier, in this situation there is little or no acceptance of a partnership approach here. The view is that patients need to be given information to help them to understand that they are sick and that their cooperation is an essential element in the recovery process. To involve them in their care makes good sense, particularly in the light of research evidence that such involvement helps to promote compliance, user satisfaction and effective treatment (Anthony & Crawford 2000).

Think of a client in whose care you have recently been involved during a clinical placement.

• Identify the various roles that individuals may have.

• How might their illness or disability affect these roles?

• How could the nurse help the client adjust to the new role demands in the short term?

• What long-term role adjustments might this client have to make?

• On your last practice placement, did the clients meet Parsons’ (1951) criteria for the sick role (see Table 19.2)?

• If they did, how?

• Have you ever taken the sick role?

LABELLING AND STIGMA

Lemert (1951) suggested two forms of deviation: primary and secondary. Primary deviation is any act that an individual may engage in before being publicly labelled as deviant. These acts are seen as relatively unimportant as they have little impact on an individual’s self-concept. What is important is society’s response to the individual. Public recognition and labelling of deviant behaviour coupled with the consequences of such identification produces a response from the individual. This response is the secondary deviation. Society’s reaction to the individual assigns a new role and status, which has an effect on how an individual sees themselves and their behaviour. The move from primary deviance to secondary deviance happens when an individual labelled as deviant by others accepts the ‘new’ social status and role.

Williams (1987) discusses deviance in relation to a medical diagnosis. Secondary deviation occurs where the diagnosis is accepted and associated with a negative social status. As a result of illness or surgery, labels such as diabetic, schizophrenic or amputee may be applied. Therefore the labelled individual is marked as different from the rest of society and may invoke negative social reactions. ‘Stigma’ is the term applied to such responses.

The seminal work on stigma was produced by Goffman (1963), who identified various sources and attributes associated with this phenomenon (Table 19.3). The negative social responses to conditions that attract stigmas are related to feelings such as fear or disgust that are attached to certain labels and the attribution of stereotypical traits to individuals. Therefore, people in wheelchairs are often viewed as both mentally and physically disabled, while someone with a mental illness is considered to be potentially violent.

| Sources | Abominations of the body Blemishes of character Tribal stigmas | Physical disabilities Mental illness, sexual deviance Race, nation, religion |

| Attributes | Discreditable | Those that are not visible or known and are therefore only potentially stigmatizing such as epilepsy, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), diabetes mellitus |

| Discrediting | Known, visible and provoking a reaction in others, for example facial disablement or deformities, symptoms of mental illness |

Sayce (2000) suggests that the concept of ‘stigma’ is not always useful as it focuses on the individual. ‘Stigma’ literally means a mark of disgrace or shame and can be seen to focus on what is wrong with the person. Thus it does not provide any foundation for challenging prejudice or improving rights for people with a disability. Rather, the focus needs to be on those who do the stigmatizing and act unfairly towards the person. In this way discriminatory practices can be highlighted and collectively acted upon.

On your last clinical placement:

• What diagnostic labels were attached to clients?

• What effect did the diagnostic label have on the client? – the client’s family? – the care team?

• How can the nurse minimize the negative effects of stigma attached to diagnostic labels?

Stigmatized ideas are culturally determined; that is they are based on society’s norms and values, which are learned early in life, and they are reinforced through everyday conversations and the media. Individuals with stigmatizing illnesses may be viewed as socially inferior and may also be subject to discrimination and socially disadvantaged. The imposing of such social disfavour may result in poor self-concept and identity. Goffman (1963) suggests that the stigmatized individual may adopt various responses when interacting with a non-stigmatized individual (Table 19.4).

| Passing | Tries to conceal attribute and pass as normal (e.g. an individual not disclosing a history of mental illness to an employer) |

| Covering | Tries to reduce the significance of the condition (e.g. attempts to resume ‘normal behaviour’) |

| Withdrawal | Opts out of social interaction with ‘normal’ people (e.g. all social activities involve others with a similar disorder) |

Finlay (2005) highlights how the labels nurses attach to patients have implications for the care received. Often patients are labelled as ‘good’ when they are seen as compliant, uncomplaining and get better; bad when viewed as less cooperative and demanding of time. However, the use of such labels is subjective. What is seen as demanding by one person may be viewed as looking for support and reassurance by another.

ALTERED BODY IMAGE

Many stigmatizing illnesses have an impact on the way an individual perceives his or her body and therefore his or her body image. Body image affects the social, spiritual, physical and psychological aspects of well-being, and as such, an understanding is vital to the provision of care (Walker et al 2006).

Price (1990) suggests that body image has an impact on the process of rehabilitation, having consequences for and affecting the client’s well-being. He identifies three components to body image:

• how individuals perceive and feel about their bodies (body reality)

• how the body responds to commands (body presentation)

• how the first two components compare with an internal standard (body ideal).

Throughout life there is an attempt to achieve and maintain a balance between the three elements (Table 19.5). Thus body image depends not only on the individual’s response to his or her own body, but also upon the appearance, attitude and responses of others. This is important for nurses to remember when delivering care, as their own responses may have a great impact on how clients perceive themselves.

| Reality | As it really is: tall/short, fat/thin, dark/fair Norm for race and relative to wider social group Not a constant state, dependent upon age and physical changes |

| Presentation | Dress and fashion Control of functions, movement and pose How others receive us |

| Ideal | How a body should look and act (culturally determined and includes size, proportion, odours and smells) Personal norm for personal space Body reliability, which may be unrealistic Applied not only to self, but to those around us |

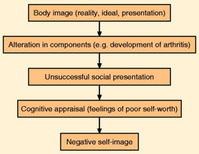

In considering Price’s (1990) work, Walker et al (2006) identify that body image and self-image are interconnected, self-image being central to an individual’s confidence, motivation and sense of achievement. It is a product of an individual’s personality, being moulded by socialization, and represents an assessment of self-worth. When the three elements of body image are in a state of equilibrium, meeting both personal and social expectations and therefore enabling a successful presentation of self, there is a corresponding positive self-image. If, however, changes occur that result in an alteration of one or more of the body image components, a negative self-image may follow (Fig. 19.1).

|

| Figure 19.1 |

Personal responses to altered body image will be influenced by a variety of factors, including:

• visibility

• associated shame or guilt

• significance for the future – work, social life, personal

• support during transition

• personal coping strategies.

Newell (2002) suggests that nurses have a role helping patients to deal with the distress associated with altered body image. There are three areas in which the nurse can take an active role

1 Public health – promoting public awareness of the issues faced by people who are subject to stigmatisation due to disfigurement.

2 Advisory role – preparing individuals who undergo procedures that may result in changes to their body image or disfigurement.

3 Providing specific interventions or referring to experts where necessary.

LOSS AND GRIEVING

Gareth Pearce, aged 23, is developing his career as a professional footballer. He played for a third division team when he was spotted by a scout for a premier league team, who subsequently signed him on. He appeared to have a promising career ahead of him. However, in his fourth match in the first team, as a result of a bad tackle, Gareth finds himself in the accident and emergency department with a fractured left tibia and fibula. He is accompanied by his wife and young son. The orthopaedic surgeon informs Gareth that he will not be playing football again for the rest of the season and that the fracture is so severe that at this stage he is uncertain whether Gareth will be able to play football again.

• What losses might Gareth and his family experience as a result of the accident and during his hospitalization?

• What responses or behaviour could this evoke?

• How might a knowledge of the grief reaction help the nurse to support Gareth and his family over the immediate crisis?

(For further information on the grief reaction see Ch. 13, ‘End of life care’.)

Grief is usually associated with death and dying, but it also occurs during other times of loss. Costello (1995) suggests that grief is the feelings that are evoked through the loss of something valued, and, as observed by McGrath (2004), there are many potential and actual losses experienced by people who have or are recovering from health threatening events. These losses relate to things such as lifestyle changes, altered physical or psychological functioning and loss of body parts. Such experiences can result in a severe emotional stress response (see Ch. 9, ‘Stress, relaxation and rest’). It can also invoke the grieving process.

In her work with terminally ill people and their families, Dunne (2005) provides an overview of the various ways in which people deal with grief and cites the classic work of Kubler Ross (1975) in which it is identified that people who face death experience a number of emotional responses(Table 19.6). She suggests that not all individuals will go through all these stages, that some may never reach acceptance, and that individuals may move to and fro between the stages. Although this process is viewed in terms of the individual’s impending ‘loss’ through their own death, it can also be applied to losses experienced from illness and disability.

Lohne & Severinsson (2005) investigated patients’ experiences of hope and suffering following spinal cord injury. Two main themes emerged.

• ‘Vicious circle’ – here people talked of feelings of loss, loneliness and dependency on others as they progressed through a cycle of good and bad days. They alternated between an acceptance of what had happened to them and the limitations this imposed and a belief that things would improve.

• Longing – every patient expressed a longing to return to their former life, leading to a constant comparison between who they were before the injury and who they had become.

All expressed the need for someone to talk to about their suffering and longing. Lohne & Severinsson suggest that nurses are ideally placed to provide patients with this type of support and therapeutic engagement.

| Stage of grief | Features |

|---|---|

| Denial | Feeling that ‘This can’t be true’, emotions are not expressed and the person tries to continue as if nothing has happened |

| Anger | Following acknowledgement of the reality an individual may express anger; this may be directed at themselves, friends, family, carers, God, everyone or everything in general |

| Bargaining | The person seeks to avoid the inevitable by proposing ‘bargains’ such as becoming a good person or going to church regularly if only they are allowed to live longer or have less pain; these ‘bargains’ are made privately or silently |

| Anger, depression | As the individual begins to feel that bargaining is futile they may lapse into depression or revert to their anger, questioning ‘Why me?’ For the person to feel this way there has to be a certain element of acceptance |

| True acceptance | Or resignation to their fate |

MOTIVATION

Motivation is an important factor in the process of rehabilitation. Motivated behaviour is described by Gross (2005) as being purposeful and goal directed. When a client’s physical ability is present, but motivation is lacking, rehabilitation can become a frustrating experience for those providing care – both for health professionals and informal carers.

Resnick (2002) identifies the understanding of motivation to be essential if the nurse is to facilitate an individual’s rehabilitation and suggests that theories related to self-efficacy, such as in the work of Bandura (1977), provide both an explanation of motivation and a framework for promoting patient activity.

Self-efficacy relates to the confidence an individual has in their ability to achieve identified goals and is seen as a strong predictor of an individual’s likelihood of overcoming barriers to success (Sherwood & Jeffery, 2000). Bandura (1977) suggests that cognitive processes play a central role in whether individuals are able to adopt and maintain new patterns of behaviour. Albery & Munafo (2008) state that self-efficacy is central to individuals’ behaviour in relation to striving to achieve goals and their response to the illness they are experiencing.

Self-efficacy is based in social learning theory in which it is suggested that individuals’ ideas about themselves are developed and learned over time. It involves four processes:

1 Performance of behaviours.

2 Observing others’ behaviours (modelling).

3 Feedback on own behaviour from valued sources.

4 Interpretation of the experience of performing the activities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree