for effective development in every professional code and educational course that you will come across in your career. This chapter will set the scene for the book; locating reflective practice within the recent historical development of professional education. Through studying this chapter and engaging in the exercises, you will be able to:

• discuss the place of reflective practice in professional education

• identify the significance of storytelling to understanding practice

• make connections between your personal beliefs, your practice and major ethical theories

• reflect on the application of reflective skills to your own professional practice and development.

Introduction

What does it mean to reflect, or to be a ‘reflective practitioner’? Is it innate, a personal way of being or learning style? Alternatively, is it something you can learn, develop and improve?

In this book, we are going to help you to discover what reflective practice is, to develop your reflective abilities, to express your reflection in ways that other people can understand and to successfully demonstrate your reflection when used for assessment. Throughout this book, we do not have any particular profession in mind. Louise is not qualified in any health or social care profession; she has worked with and supported health and social care students, and writes plays about health and illness. Janet is a nurse by background; she works in higher education in a multi-professional setting. We draw on literature from health, medicine, social work, dentistry and education, in fact from any discipline that we think adds to understanding and offers useful ideas. Naturally, we draw on our own experience but we use stories and illustrations from many professional viewpoints, in order to demonstrate that reflection crosses inter-professional language and practice.

In order to start on this journey, we want to offer three areas for consideration:

(1) A short history of reflective practice, where it came from and why it has become so important.

(2) The use of stories – storytelling is a powerful medium for reflection. It offers a structure in which to narrate actual events, but also the freedom to explore safely thoughts and feelings that may be taboo. We will frequently use stories in this book and will help you to develop your own skills of narration.

(3) Ethical practice – questions about what is the right way to behave are rarely far from view when we engage in reflection. There is no single way to decide on the most ethical course of action and frequently no perfect answers. Here we will explain ethical theories and suggest one framework we think is particularly suitable for thinking about ethics as you reflect on your practice.

A short history of reflective practice

The industrial revolution is probably as good a starting place for this as any. In the nineteenth century, the mechanization Reflection in context of just about everything from transport to food production changed the way people all over the world worked and lived their lives. Central to this revolution was the application of scientific methods – if you can observe and measure, then you can predict and control. The effects of this scientific explosion were not just concerned with factories or industry; the philosophy behind them infiltrated every aspect of human life. In medicine, health and social care, the human condition was investigated, dissected, measured and categorized.

A great deal of good has come from these developments. In medicine, the discovery of bacteria and viruses has transformed our understanding of disease (Le Fanu, 1999). Psychological research has led to greater understanding of how the human mind works, revolutionizing the care of people who are mentally ill (Rodham, 2010), and theories from sociology have given us ways of explaining and predicting human behaviour (Cohen & Kennedy, 2007).

However, the downside to this focus on science was that, by the twentieth century, its dominance was such that knowledge gained from scientific methods seemed more important than any other sort of knowledge. Many people challenged this view, but it was Donald Schön’s seminal work, published originally in 1983 and 1987, that challenged the scientific method in professional education (Schön, 1991): reflective practice was born.

Schön’s argument goes like this:

The cliff top and the swamp

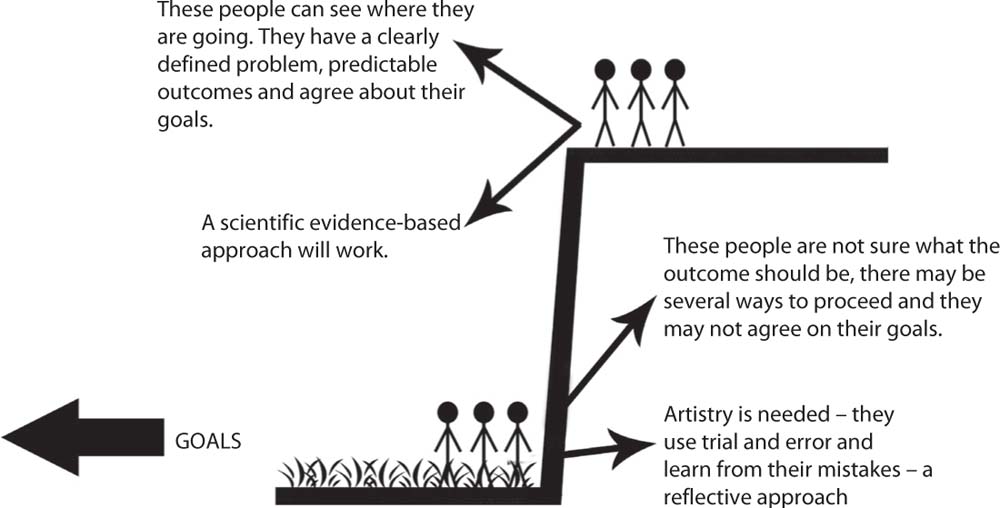

Imagine you are with a group of people who are on a journey (see figure 1.1). You come to a cliff top and can see a range of possible destinations in the distance. You need to decide on the correct destination and best route to get there. The various paths below you are clear to see; you can trace each one, plan ahead, decide on a direction and continue on your way.

Another group of people are also trying to reach their destination, but they are starting from the bottom of the cliff, where the ground is swampy. They cannot see clearly ahead and the destination is out of sight, so they do not know which may be the best path to take. They use trial and error, learning from their mistakes and picking up new information as they pick their way carefully through the swamp.

Figure 1.1 The cliff top and the swamp (adapted from Schön, 1991)

For Schön, the scientific approach available to the cliff-top people, which he calls ‘technical rationality’, is fine where problems have definition and clarity, outcomes are predictable and all the people involved have shared goals. However, he claims that problems in professional life are rarely this simple. We are often uncertain about what the problems might be, have limited research to guide us, and disagree about what the best course of action is. In these situations, the skills developed by the swamp people are much more effective. This – the ‘artistry’ of professional practice – is the skill-set Schön sought to teach, develop and constantly improve through reflective practice.

A reversal of priorities

Schön looked around him and started to analyse the way in which professionals were educated. He noticed a hierarchy in highly regarded professions where the most attention and Reflection in context value were given to theory, followed by application of knowledge, and finally by skills and everyday practice. For example, a barrister or attorney studied the theory of law for several years before having the opportunity to practise, and medical students studied anatomy and physiology long before they met their first patient. As professions with an apprentice basis, such as allied health and social work, nursing and midwifery, aspired to greater professional status, they too began to adopt these principles. Much has changed in professional education in the last few decades, the privileging of theoretical learning over practice learning is no longer as common and most professional courses include at least some development of the skills and artistry of the profession right from the start. It may therefore seem that the trend has been reversed.

Or has it?

Despite these changes, professions remain very guarded and defend the ‘knowledge’ that they see as central to their unique practice. Think about the last place you worked, or attended for a placement. Who earned the most money, had the most power or gained the most respect as a professional person? It is much more likely that this person also had the longest period of education and the most academic qualifications.

Evidence-based or research-based practice still privileges quantitative rather than qualitative methods of enquiry. Projects that use scientific methods, for example predicting the probability of a cause-and-effect relationship, or the effectiveness of a new policy, treatment or drug, are more likely to gain funding.

So, whilst there has been a great deal of change, there remains ambivalence about the place of the artistry or craft basis of professional behaviour.

Deconstructing reflective practice

Example 1: a child learning a skill

| Activity | Analysis |

| A sunny day in the park; a young child is poised at the top of a sloping grassy bank about to cycle down it without trainer wheels for the first time. The adult observing from a distance sees much theory is evident. Forces of gravity, mass, kinetic energy and velocity act on the child and the bike’s frame as s/he shakily proceeds down the hill. The focus is on staying upright but the presence of ‘theory in use’ is all around. | Theory in use |

| Despite being young, s/he already brings a wealth of knowledge to the problem. S/he knows how to coordinate limbs and eyes to progress forward, and to shift body weight from left to right to avoid falling. S/he has also already mastered the art of steering using the handlebars whilst riding with trainer wheels. The child will probably not be able to articulate an understanding of gravity but knowledge of its effect is evident from observed behaviour. This ‘knowledge in use’ is added to and refined every time s/he gets onto the bike. | Knowledge in use |

| The child is absolutely focused on the task in hand – in the moment, s/he concentrates, appraises how well s/he is doing, adjusts balance, speed and steering. | Reflection in action |

| Arriving shakily at the bottom of the hill, the child thinks back over the event – powerful feelings of pride at staying upright and relief at not being too badly hurt – a few cuts and grazes but nothing worse! S/he thinks about what was good and how to improve – the adults give praise, ask questions about feelings and give feedback on performance – this greatly enhances the child’s ability to ‘reflect on action’. | Reflection on action |

| Many cycle rides later, we see this young person riding through town. Mastery of the bike is evident as we watch a skilfully, smoothly executed turn at speed: observing traffic, wind speed, road conditions, pot holes and pedestrians, our cyclist rides the bike with ease. This thoughtful, engaged, conf dent cycling is an example of ‘reflective practice’ – learning continues with every journey taken and the skill is evident in the performance. | Reflective practice! |

Example 2: the child is now the adult

| Activity | Analysis |

| Our young person is now an adult, engaged in a professional conversation. Theories of communication are evident in body language, eye contact and verbal and non-verbal communication techniques. | Theory in use |

| The person in conversation is showing anger – raised voice, wide gestures, aggressive stance. Our professional sits back a little, uses open body language, active listening and questions to understand and dissipate the angry response – knowledge in action is evident from the behaviour displayed. | Knowledge in use |

| S/he may look relaxed but inside his/her mind is racing: ‘How am I doing?’ ‘What should I say next?’ ‘What questions will get the best reaction?’ ‘What has worked before?’ S/he engages in a constant internal narrative, appraising feelings and combining theoretical understanding and experience; reflecting in the moment helps to navigate through a potentially difficult situation. | Reflection in action |

| Reflecting back on the encounter, our professional analyses his/her skills and the outcomes of the conversation. S/he is excited and pleased to have managed a difficult situation well, but by narrating the event to a supervisor more can be learned. The supervisor asks probing questions offering challenges and alternative views. | Reflection on action |