In practice, much reflection takes place in groups rather than individually. Group reflection brings with it another set of issues and debates: differences of perception, conflicting stories, competing truths and tensions between different disciplines. This chapter will explore how reflection can be shared between professionals without losing individual perspective and expertise. We will talk you through the process of organizing and running a reflective group yourself, and demonstrate that, used well, collective knowledge is stronger and better able to effect change than individual knowledge. Through studying this chapter and engaging in the exercises, you will be able to:

• understand the importance of shared reflective practice and inter-disciplinary working

• explore being part of a group whilst retaining your individuality

• listen to others without feeling threatened by their different perception of a situation

There is a lot of theory on groups and the way they operate. You will have experienced yourself the way you behave differently when you are alone, with your family, your friends or your professional colleagues.

| TIME FOR REFLECTION |

Stop for a moment and list the main groups that you are a member of. How many did you get to?

You may have included a group of people you work with, the whole student group for your course, or a sub-group; this may be friends whom you choose to associate with, but may also be a group designated by your course leader where you have no choice of membership. You probably have membership of some social groups too: you may be part of a family group, a member of a club or society. The size of a group can be very variable, from just three or four people to hundreds, or, in the case of a social network site, thousands of people may be collectively in touch with each other.

Your role within the group will also vary. In some, you may be the leader; in others, you may be an employee, connected by family or personal interests, or a volunteer. Some groups may have a defined purpose – to complete a work task or a piece of course work for assessment; others may be more open and less defined. In this chapter, we are interested in group reflection, so smaller groups where people are able to have a collective discussion are the focus.

| SEARCH AND EXPLORE |

There is a huge amount of online information about groups. Try searching for ‘group dynamics’ to explore what ‘sort’ of group member you may be, and what an ideal group may consist of. But do not get sidetracked by this; we are more interested in group reflection, and how this can enhance your practice.

Why reflect in a group?

What is the weather like today? You may think it’s a nuisance that it’s snowing because you’ll have to wear your coat and leave early. Your neighbour might be smiling because the slugs and snails will be killed by the cold. Children will be excited and drivers will be anxious.

If all of these people come together in a group reflection, their perceptions of the day and emotional responses will be very different. Group reflection on practice will contain similar differences of perception in which your beliefs and personal preferences will be challenged.

In earlier chapters, we have concentrated mostly on you as an individual. But in your practice as a student and your working life, you will usually be part of a professional group where people have different levels of qualification and responsibility. When you meet together to discuss your cases, professional differences and complex hierarchies will be involved. Reflecting on your own allows you to hold on to a particular opinion without being challenged. In a group, you have to accept somebody may disagree with you: by keeping an open mind, you may understand something differently and change your opinion. This openness is what all good practitioners aspire to.

Although few professionals work in complete isolation, most models of reflection are written as if they apply to an individual. It is also the case that a lot of reflective learning is taught in uniprofessional groups where ‘professional boundaries and traditional delineated roles may be reinforced rather than reduced’ (Karban & Smith, 2010, p. 176). Although reflecting on positive and negative situations is of equal importance, they argue that critical reflection in an inter-professional situation, which requires the exploration of wider social and political issues, will lead to professional decisions and professional differences being highlighted and challenged.

Fook and Gardner (2007) show how a four-stage model probing these wider social and political issues can form a valuable structure for bringing challenge and criticality into group reflection. Whatever the trigger for a group reflection, its purpose is to enable everyone to learn and move on. At its best, the outcome could be as significant as a change in the way services are delivered.

One of the reasons we are writing this book without a particular profession in mind is to encourage you to reflect personally and within groups, rather than just seeing issues from your own perspective. We have said that reflection has the capacity to embed good practice; record thinking processes; develop skills; improve practice; and, crucially, to move difficult situations forward. Group reflection can achieve all of these outcomes but can be destructive and unhelpful if it is not well managed.

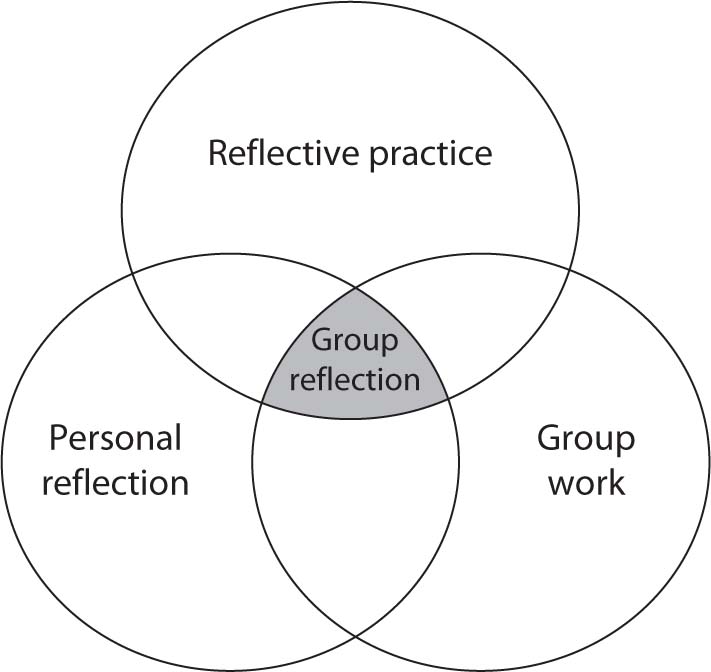

In this chapter, we will include some pointers to literature that we think may be helpful but we are not offering a detailed critique of the literature on group work and group dynamics: this is well researched and published elsewhere. What we do want to do is to explore the space where personal reflection, reflective practice and being in a group overlap (see figure 5.1). The skills involved in personal reflection may not be the same as those needed for a group, and skilful group work is not necessarily reflective. By focusing on this area of overlap, we aim to help you to think about how to reflect in this particular ‘space’ and how you might facilitate reflection with others.

Figure 5.1 Group refl ection

There are several things that are special about this space. You remain ‘I’, but you are also one of ‘us’. You have a professional identity but also a team identity where the team members may all be of the same profession, but might all be different. Your personal and specialist views are just as important as when you reflect alone, but will need to be mediated through the group interaction. You will also have personal feelings and preferences about reflection.

| TIME FOR REFLECTION |

Focus on an issue that you have been thinking about and look at the three rings of the diagram in figure 5.1. In which area would you feel most comfortable reflecting on this issue? Is the central group reflection the least or most acceptable to you? Why?

We all have different identities; the phrase ‘Identity negotiation’ (Swann, Johnson & Bosson, 2009, p. 82) describes a process that: ‘transform[s] disconnected individuals into collaborators who have mutual obligations, common goals, and often, some degree of commitment to one another’. Negotiating who you are – your identity as an individual, professional and colleague within a group reflection – is an important part of your personal commitment to that group.

We have identified eight elements of a group that we believe will be significant in ensuring successful outcomes where the focus is reflection:

Getting together

Getting together

People

People

Talking and listening

Talking and listening

Being non-judgemental

Being non-judgemental

Being ‘in the room’

Being ‘in the room’

Opening

Opening

Contributing

Contributing

Outcomes

Outcomes

Getting together

Getting together

When you meet as a group, the first decision is where and when. This brings a structure to the meeting. The spontaneity you have when reflecting alone is lost. Arranging something at a time when everyone is available often leads to a least-worst scenario.

Where you meet is also a key factor. All space has connotations. We are most comfortable in our own space with our own things around us, but often you will be meeting in a space that you wouldn’t choose, or somebody else’s office. You may resent the time you spend going to an out-of-the-way place which has obviously been chosen for someone else’s convenience. You may be used to reflecting in comfort but have instead to sit on children’s chairs. You might like to move around when reflecting but now you are constrained.

There is also a time pressure. Very often, group reflection takes place at the end of the day. People are tired, worrying about getting home and already trying to plan the next day. You are not sure what is going to happen in the meeting, you may not even know exactly who is going to be there.

A further factor will be the reason for getting together. This may be a positive joint decision by a group of colleagues to reflect on their practice, or a management requirement where individuals feel they do not have a choice about joining in. Worse still, they may feel their ‘performance’ in the group is being assessed and judged by others. Where reflecting in groups is a ‘requirement’, spontaneity and willingness to engage may be lost (Platzer, Blake & Ashford, 2000).

| EXERCISE |

‘Why?’, ‘What?’, ‘Where?’, ‘When?’ and ‘Who?’ are not bad starting places…

Have a look at the group reflection checklist (table 5.1 on p. 104) to see whether you agree with our points.

People

People

Who is in the room will influence what happens in the room.

Miller’s reflection on her own role as a reflective group facilitator offers a powerful insight into reflective group dynamics (Miller, 2005). She talks about facilitating groups as being in a ‘difficult and uncomfortable space’ (p. 368) where the reactions of the people in the group and the outcomes cannot be easily predicted.

We all respond in different ways to things like superiority, experience, maturity and inter-professional dynamics. The group may be led by someone you trust and respect, by someone you do not feel that you can be honest with, or even by an external facilitator whom you have never met before. Equally, the members of the group may be a positive or negative influence on how you are feeling, and your willingness to engage.

| TIME FOR REFLECTION |

Stop for a moment and think about how you come across in a group setting. How does it make you feel? Are you able to be open and comfortable, or do you feel defensive? What skills do you already have, and what might you need to develop?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree