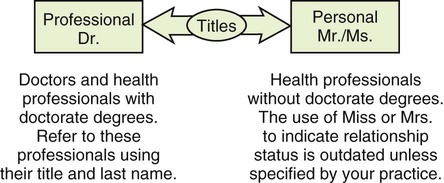

Chapter 2 The second purpose of business etiquette is to do your part to make your facility a great place for you and your colleagues to work. A sense of business etiquette contributes to the smooth flow of operations in an environment that is often stressful and chaotic. Business etiquette contributes to clear communication, mutual support, and, ultimately, the delivery of quality health care. This requires flexibility and open-minded acceptance. For example, today’s workplace is comprised of four generations (discussed more thoroughly in Chapter 7). You have to be able to step outside of your own generation and interact professionally with people of all ages. Aside from people of different ages, you will likely encounter clients and colleagues from dozens of different ethnic, national, and cultural backgrounds. “Dr. Tolland, this is Jim Holtz, the new Medical Assistant,” and she says, “Hi Jim, I’m Monica Tolland. Welcome aboard,” you should assume that she is just being friendly and is not inviting you to call her by her first name, unless she specifically says so. You should reply, “Thank you, Dr. Tolland. It’s nice to meet you.” If that is where it ends, then she is Dr. Tolland to you. See Figure 2-1 for a diagram on appropriate uses of titles. “Mr. Adler, this is Dr. Berthold, the physician on duty today. Dr. Berthold, this is Saul Adler.” “Ms. Christy, this is Ms. Izzo, the Radiologic Technician. Ms. Izzo, this is Callie Christy.” “Dr. Apollo, this is our new Surgical Technician, Sue Hale. Sue, Dr. Apollo is the Chief Resident.” Introductions can be confusing at times, mainly because most people are over-eager to make a good first impression. Protocols for making proper introductions are summarized in Box 2-1. * Let work be therapeutic for you. Even on the worst day, there are many positive aspects of work, such as the people you enjoy seeing, or specific activities you like tackling. Consider throwing yourself into your work as a means of shoving your other problems and concerns to the back of your mind. * Act “as if …” Even if you don’t feel like it, act the way you wish you felt. Act as if you are friendly. Act as if you are enthusiastic. Force yourself to smile. Chances are that your mood will get swept up in the act, and your day will go better. * Stop and reframe. Cognitive psychologists urge people to reframe their outlook to gain a new perspective. Can you reframe your perspective on your problems by imagining how much worse they could be? Can you make a problem smaller in your mind by telling yourself that you will deal with it little by little until it’s solved, just like the vast majority of problems you have ever encountered? Can you put the problem out of your mind by telling yourself that there is nothing you can do about it while you are at work, and you will confront the problem later at an appropriate time? If the problem is a work-related conflict, try simply resolving to take the high road rather than engage in disputes that are likely to be both petty and short-lived. * Practice mindfulness and relaxation techniques. Every time you have a quiet moment, close your eyes and take some deep breaths to clear your mind. If you are feeling irritable, pause before you respond to someone and choose your responses thoughtfully. Without sharing too many details, explain to your co-workers that you are having a bad day and appreciate their understanding. Finally, realize that bad times don’t last forever and resolve to make the next day better. * Make reasonable allowances. Most people have good intentions, so a bad day can be tolerated now and then. * Be willing to listen. If you are close to the person, you can offer to listen to them. Ask them if there is anything you can do to help. * Know when to step aside. Naturally, if someone else’s bad days are extensive enough to be chronic behavior problems, they are beyond your capacity to help. These are matters for supervisors and Human Resource professionals. If someone else’s behavior becomes problematic for you, discuss the issue privately with your manager.

Ready for Work

Act and look like a health care professional.

Act and look like a health care professional.

Become someone other people look forward to seeing at work.

Become someone other people look forward to seeing at work.

Understand how your appearance affects your success.

Understand how your appearance affects your success.

Fit in well with a variety of different people.

Fit in well with a variety of different people.

Represent your employer to its customers.

Represent your employer to its customers.

Develop self-reflection to change your habits and improve your performance.

Develop self-reflection to change your habits and improve your performance.

Modeling Business Etiquette

Learning Objectives for Modeling Business Etiquette

Understand your role in the support and success of the business where you work.

Understand your role in the support and success of the business where you work.

Identify behavioral clues of your fellow workers.

Identify behavioral clues of your fellow workers.

Make introductions easily and smoothly.

Make introductions easily and smoothly.

Understand the importance of titles.

Understand the importance of titles.

Build your conversation skills.

Build your conversation skills.

Learn to be on time and to be discreet.

Learn to be on time and to be discreet.

Practice the little courtesies that make a big difference.

Practice the little courtesies that make a big difference.

The Purposes of Business Etiquette

Skills to Improve Your Business Etiquette

Conversation at Work

Respecting Professional and Personal Titles

Professional Titles

Making Introductions

When Someone Is Having a Bad Day

Tackling Your Own Bad Days

Helping a Co-worker Experiencing a Bad Day

Ready for Work

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access