CHAPTER 5 Questions about the effects of interventions

examples of appraisals from different health professions

This chapter is an accompaniment to the previous chapter (Chapter 4) in which you learnt how to critically appraise evidence about the effects of interventions. In order to further illustrate the key points from Chapter 4, this chapter contains a number of worked examples of questions about the effects of interventions. As we mentioned in the preface of the book, we believe that it can be easier to learn the process of critical appraisal when you see some worked examples of how it is done, and it is even better when the examples are from your own health profession. Therefore, this chapter (and Chapters 7, 9 and 11) contains examples from a range of health professions. Some of the clinical examples are relevant to more than one health profession. Each example is formatted in a similar manner and contains the following elements:

You will notice that in most of the examples the type of article that has been chosen to be appraised is a randomised controlled trial. You may wonder why this is the case when Chapters 2 and 4 explained that systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials should be the first choice of study design to answer questions about the effects of intervention. There is a good reason behind this. The authors of the examples that are contained in this chapter were asked to not choose (or indeed, specifically search for) systematic reviews if they were available to answer their question. Why? Because it is easier to learn how to appraise a systematic review of randomised controlled trials if you have first learnt how to appraise a randomised controlled trial. This chapter and Chapter 4 are designed to help you learn how to appraise a randomised controlled trial. Once you know how to do this, Chapter 12 will help you to learn how to appraise a systematic review. As you read through these examples, keep in mind that because the suggestions that the authors of these worked examples have provided in the ‘how might we use this evidence to inform practice’ section have been drawn from only one individual study, in reality, additional studies would need to be located and appraised prior to drawing clear conclusions about what should be done in clinical practice.

When appraising an article, you need to obtain and carefully read the full text of the article. We have not included the full text of the articles that are appraised in the example. However, for each of the examples in this chapter (and Chapters 7, 9 and 11), the authors of the examples have prepared a structured abstract that summarises the article. This has been done so that you have some basic information about each article. As we mentioned in Chapter 1, the more you practise doing the steps of evidence-based practice, the easier it will become. This is particularly true of the critical appraisal step. You may find it useful if you approach these worked examples as a self-assessment activity and try and obtain a copy of the article that is appraised in each of the examples (or just the ones that are relevant to your health profession if you feel more comfortable with that). You can then critically appraise the articles for yourself and check your answers with those that are presented in the worked examples.

One other thing to note about the examples in this chapter (and Chapters 7, 9 and 11) is that the appraisal of articles is not an exact science and sometimes there are no definite right or wrong answers. As with evidence-based practice in general, the health professional’s clinical experience has an important role to play, particularly in deciding about issues such as baseline similarity (as we saw in Chapter 4) and clinical significance (as we saw in Chapters 2 and 4). Some of the examples may contain statements that you do not completely agree with and that you, as a health professional, would interpret a little differently. Also, the examples are provided to give you an overall sense of the general process of evidence-based practice. The content that is presented in the examples is not exhaustive (particularly in the ‘how do we use this evidence to inform practice’ section) and there may be other factors or issues that you, as a health professional, would suggest or consider if you were in that situation. That is OK.

Occupational therapy example

Search terms and databases used to find the evidence

Search terms: ‘rheumatoid arthritis’ AND ‘joint protection’

Structured abstract

Study design: Randomised controlled trial.

Setting: Outpatients from the occupational therapy departments of two hospitals in the UK.

Follow-up period: 12 months. Assessments were performed at baseline, 6 months and 12 months.

Is the evidence likely to be biased?

Yes. Participants were randomly allocated, using a four-block sequence.

Yes. Allocation occurred using sealed envelopes that had been prepared in advance.

No. For this trial, it was not possible for participants to be blinded to group allocation.

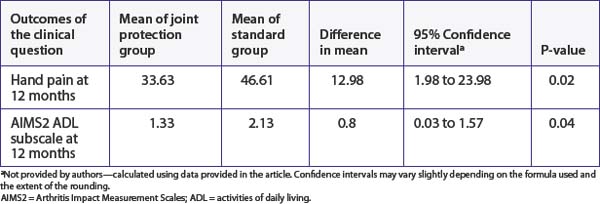

What are the main results?

we consider that the upper end of the confidence interval is 1.57, it is possible that the effect of this intervention could be clinically significant for some people. As explained in Chapter 4, the decision about clinical significance is a subjective one and depends on a number of factors such as the costs involved and preferences of the individual concerned.

Physiotherapy example

Clinical question

Does preoperative inspiratory muscle training in addition to standard care prevent postoperative pulmonary complications in clients who are undergoing CABG surgery?

Search terms and databases used to find the evidence

Database: PEDro (using the ‘Advanced Search’ option)

Structured abstract

Study design: Randomised controlled trial.

Setting: University medical centre in Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Main results: Postoperative pulmonary complications occurred in 25 (18%) of the participants in the intervention group and 48 (35%) of the control group, odds ratio 0.52 (95% CI 0.30 to 0.92). Median duration of hospitalisation was 7 days (range 5–41) in the intervention group and 8 days (range 6–70) in the control group (p = 0.02).

Is the evidence likely to be biased?

Yes, participants were appropriately randomised, with a computer-generated number list.

Yes, the number list was sealed in envelopes which were held by an external investigator.

No. For this trial, it was not possible for participants to be blinded to group allocation.

Yes. The investigators who assessed outcomes were blinded to participants’ treatment group.

Yes, it is stated that an intention-to-treat analysis was conducted.

What are the main results?

Pulmonary complication: The risk of pulmonary complications is presented appropriately, using an odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval (refer to Table 5.2). The reduction in risk is both statistically and clinically significant. The 95% confidence interval includes only clinically worthwhile reductions in risk. Therefore, the results are sufficiently precise to make clinical recommendations.

This data for the first outcome, pulmonary complications, can be used to estimate two useful statistics. First, let us calculate the absolute risk reduction (ARR), which is simply the risk in the control group minus the risk in the intervention group: 35% – 18% = 17%. Using the formula (95% confidence interval ≈ difference in risk  ) that was provided in Box 4.3 in Chapter 4, you also calculate the 95% confidence interval of the ARR to be 9% to 25%. The ARR statistic is useful in clinical practice because, if you decide to implement the intervention, you can use it to explain to clients the value that they can expect from undertaking the inspiratory muscle training regimen. After explaining what a pulmonary complication is and how it can delay recovery, many clients would consider the training program worthwhile to reduce their risk of such a complication from 35% to 18%.

) that was provided in Box 4.3 in Chapter 4, you also calculate the 95% confidence interval of the ARR to be 9% to 25%. The ARR statistic is useful in clinical practice because, if you decide to implement the intervention, you can use it to explain to clients the value that they can expect from undertaking the inspiratory muscle training regimen. After explaining what a pulmonary complication is and how it can delay recovery, many clients would consider the training program worthwhile to reduce their risk of such a complication from 35% to 18%.

How might we use this evidence to inform practice?

You decide that the trial is valid and that the results are important. Pulmonary complications are dangerous and uncomfortable for the client and they are expensive to treat. Therefore, the effect of this intervention on this outcome alone is clinically worthwhile, and the number needed to treat of six is useful in justifying the introduction of the service. Further justification of the clinical worth of this intervention comes from the other significant outcome, which was a reduction in the duration of hospitalisation. You plan to discuss the results of this study with your head of department as there are resource implications associated with introducing the service, particularly providing an intervention of the same intensity as was provided in the study. However, it is your recommendation that this intervention should be introduced.

Podiatry example

Search terms and databases used to find the evidence

This search produced 23 hits, including 4 Cochrane Reviews, 18 trials and 1 economic evaluation. One of the Cochrane Reviews titled ‘Interventions for the treatment of plantar heel pain’ looks like it may address your question. Reading through the review you find it included only one trial evaluating the impact of orthoses and that this trial compared orthoses with stretching exercises. You also notice that the search for studies was only conducted up to 2002. You go back to your search to see if there are any trials published subsequent to the review that may answer your question. After looking over the titles and abstracts of the trials you are drawn to two articles that compare the effectiveness of different types of orthotic devices. They are both randomised trials conducted in patients with a diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. You select the trial titled ‘Effectiveness of foot orthoses to treat plantar fasciitis’ to read as it had a longer follow-up (12 months instead of 2 months) and looks at the effect of orthotic devices on both pain and function.

Structured abstract

Study design: Randomised controlled trial.

Setting: A university podiatry clinic, Melbourne, Australia.