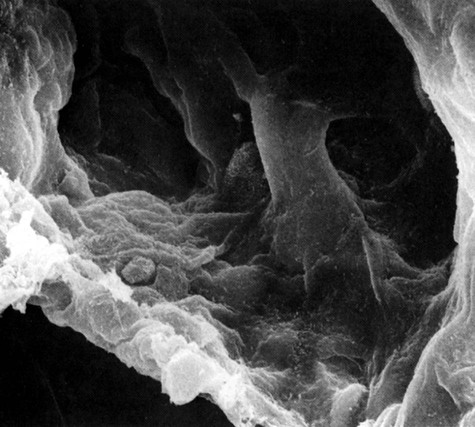

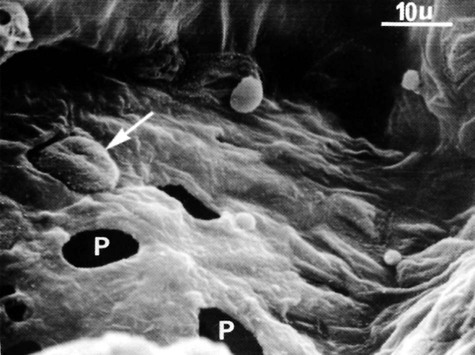

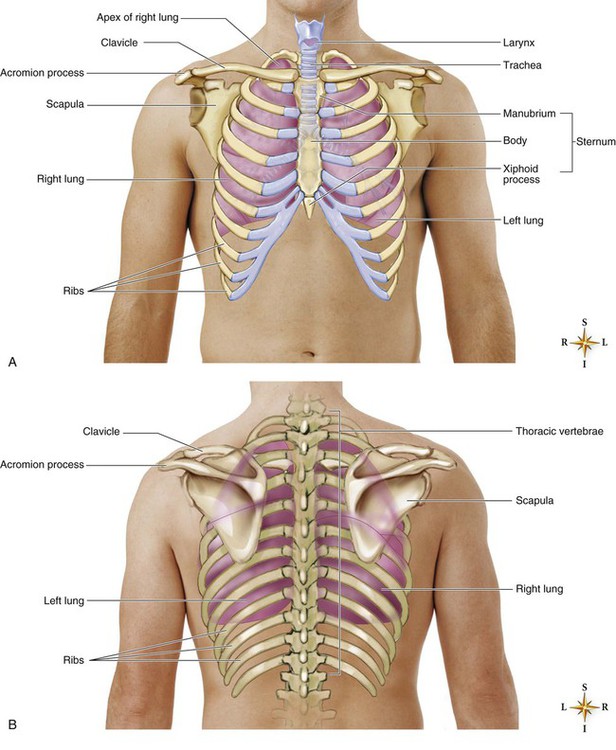

The thoracic cage is a cone-shaped structure that is rigid but flexible. It must be somewhat rigid to protect the underlying structures, but it must be flexible to accommodate inhalation and exhalation. The cage consists of 12 thoracic vertebrae, each with a pair of ribs. Posteriorly, each rib is attached to its own vertebra, but anteriorly, attachment varies (Fig. 17-1). The first seven pairs of ribs are attached directly to the sternum. The 8th, 9th, and 10th pairs are attached by cartilage to the ribs above. Because the 11th and 12th ribs have no anterior attachment, they sometimes are referred to as floating ribs. The second rib is attached to the sternum at the angle of Louis, which is the raised ridge that can be felt just below the suprasternal notch.1 The lungs are cone-shaped organs that have a total volume of approximately 3.5 to 8.5 liters. The superior portion is known as the apex, and the inferior portion is known as the base. The apical portion of each lung rises a few centimeters above the clavicle (see Fig. 17-1). Each lung is firmly attached to the thoracic cavity at the hilum and at the pulmonary ligament.2 The lungs are divided into lobes and segments (Fig. 17-2), with the lobes being separated by pleural membrane-covered fissures. The right lung, which is larger and heavier than the left, is divided into upper, middle, and lower lobes. The left lung is divided into only an upper and a lower lobe.2 A portion of the left lung, the lingula, corresponds anatomically with the right middle lobe. The horizontal fissure divides the right upper lobe from the right middle lobe. The oblique fissure divides the right upper and middle lobes from the lower lobe and the left upper lobe from the lower lobe. The lobes are divided into 18 segments, each of which has its own bronchus branching immediately off a lobar bronchus. Ten segments are located in the right lung and eight in the left lung.1 The area between the two lungs, the mediastinum, contains the heart, great vessels, lymphatics, and the esophagus. A portion of the mediastinal area contains the root of the lungs, also known as the hilum, in which the visceral and parietal pleural membranes form a sheath around the main stem bronchi, the major blood vessels, and the nerves that enter and exit the lungs.2 The pleura is a thin membrane that lines the outside of the lungs and the inside of the chest wall. The visceral pleura adheres to the lungs, extending onto the hilar bronchi and into the major fissures. The parietal pleura lines the inner surface of the chest wall and mediastinum.2 The two pleural surfaces are separated by an airtight space, which contains a thin layer of lubricating fluid. Pleural fluid allows the visceral and parietal pleural membranes to glide against each other during inhalation and exhalation.1,3 The pleural space has the capacity to hold much more fluid than its normal volume of a few milliliters.1 The pleural space has a pressure within it called the intrapleural pressure, which differs from the intrapulmonary (pressure within the lungs) and atmospheric pressures.4 Under normal conditions, intrapleural pressure is less than intrapulmonary pressure and less than atmospheric pressure, with a normal range of −4 to −10 cm H2O during exhalation and inhalation, respectively.3 A deep inhalation can generate intrapleural pressures of −12 to −18 cm H2O. This negative intrapleural pressure results from forces within the chest wall that exert pressure to pull the parietal pleura outward and away from the visceral pleura, while the elastic fibers within the lungs exert pressure to pull the visceral pleura inward away from the parietal pleura. The constant pull of the two pleural membranes in opposite directions causes the pressure within the space to be subatmospheric.4 The negative pressure in the pleural space keeps the lungs inflated (Box 17-1). If atmospheric pressure enters the pleural space, all or part of a lung will collapse, producing a pneumothorax.1 The muscles of ventilation (Fig. 17-3) are governed by the regulatory activity of the central nervous system, which sends messages to the muscles to stimulate contraction and relaxation. This muscular activity controls inhalation and exhalation. Muscles that increase the size of the chest are called muscles of inhalation; those that decrease the size of the chest are called muscles of exhalation.5 The main muscle of inhalation is the diaphragm. The diaphragm is a dome-shaped, fibromuscular septum that separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities. It is connected to the sternum, ribs, and vertebrae. During normal, quiet breathing, the diaphragm does approximately 80% of the work of breathing. On inhalation, the diaphragm contracts and flattens, pushes down on the viscera, and displaces the abdomen outward. Diaphragmatic contraction also lifts and expands the rib cage to some extent.1,5,6 The action of the diaphragm is governed by the medulla, which sends its impulses through the phrenic nerve. The phrenic nerve arises from the cervical plexus through the fourth cervical nerve, with secondary contributions by the third and fifth cervical nerves. For this reason and because the diaphragm does most of the work of inhalation, trauma involving levels C3 to C5 causes ventilatory dysfunction.5 Other muscles of inhalation include those that lift the rib cage. The most important of these are the external intercostal muscles, which elevate the ribs and expand the chest cage outward. The scalene, anterior serratus, and sternocleidomastoid muscles also participate to elevate the first two ribs and sternum.1,5,6 Exhalation in the healthy lung is a passive event requiring very little energy. Exhalation occurs when the diaphragm relaxes and moves back up toward the lungs. The intrinsic elastic recoil of the lungs assists with exhalation. Because exhalation is a passive act, there are no true muscles of exhalation other than the internal intercostal muscles, which assist the inward movement of the ribs. During exercise, however, exhalation becomes a more active event, requiring some participation of the accessory muscles of ventilation. Several muscles of the abdomen are thought to contribute to active exhalation.4,5 The accessory muscles of ventilation usually are considered to be those that enhance chest expansion during exercise but that are not active during normal, quiet breathing. These muscles include the scalene, sternocleidomastoid, and other chest and back muscles, such as the trapezius and the pectoralis major.1,5,6 The conducting airways consist of the upper airways, the trachea, and the bronchial tree. The purposes of the conducting airways are to warm and humidify the inhaled air, to act as a protective mechanism that prevents the entrance of foreign matter into the gas exchange areas, and to serve as a passageway for air entering and leaving the gas exchange regions of the lungs.1–3 The upper airways consist of the nasal and oral cavities, the pharynx, and the larynx (see Fig. 17-4). Their main contribution to ventilation is the conditioning of inspired air. Conditioned air is air that has been warmed, humidified, and cleansed of some irritants. Warming and humidifying, which are essential to prevent irritation of the lower airways, occur mainly within the nose by means of a dense vascular network that lines the nasal passages. The air is cleansed by the coarse hairs that line the nasal passages and filter large inhaled particles.1,3 The epiglottis is located in the upper airways. It protects the lower airways by closing the opening to the trachea during swallowing so that food passes into the esophagus and not the trachea. The epiglottis is a thin, leaf-shaped, elastic cartilage that is located directly posterior to the root of the tongue and attached to the thyroid cartilage (see Fig. 17-4). It opens widely during inhalation, permitting air to pass through the trachea into the lower airways.1 The trachea is a hollow tube approximately 11 cm (4.5 inches) long and 2.5 cm (1 inch) in diameter (Fig. 17-5). It begins at the cricoid cartilage and ends at the bifurcation (major carina) from which the two main stem bronchi arise. The carina is positioned approximately at the level of the aortic arch, the fifth thoracic vertebra,7 or just below the level of the angle of Louis.1 The trachea consists of smooth muscle supported anteriorly by 16 to 20 C-shaped, cartilaginous rings. They prevent tracheal collapse during bronchoconstriction and strong coughing. The posterior wall of the trachea lies contiguous with the anterior wall of the esophagus. Having no cartilaginous support, this wall is composed only of muscle tissue, which is separated from the anterior esophageal wall by loose connective tissue (see Fig. 17-5, inset).1 The two main stem bronchi are structurally different (see Fig. 17-5). The left bronchus is slightly narrower than the right, and because of its position above the heart, the left bronchus angles directly toward the left lung at approximately 45 to 55 degrees from the midline. The right bronchus is wider and angles at 20 to 30 degrees from the midline. Because of this angulation and the forces of gravity, the most common site of aspiration of foreign objects is through the right main stem bronchus into the lower lobe of the right lung.2,3 Each branching of the tracheobronchial tree produces a new generation of tubes (Fig. 17-6). The main stem bronchi are the first generation; the next branch, the five lobar bronchi, is the second generation. The third generation includes the 18 segmental bronchi. The fourth through approximately the ninth generations are referred to as the small bronchi, beginning with the subsegmental bronchi. In these bronchi, diameters decrease; however, because the number of bronchi increases with each generation, the total cross-sectional area increases with each generation. This great increase in the cross-sectional area of the lung is significant because it allows easy ventilation despite decreasing airway lumens.1 The final subdivision of the conducting airways is the bronchioles. These tubes have a diameter less than 1 mm and have no connective tissue and cartilage within their walls. Their walls do, however, contain smooth muscle.2 When smooth muscle constriction occurs, these airways may close completely because of the lack of structural support. The terminal bronchioles form the last branch of the conducting airways, after which the gas exchange areas of the lungs begin. There are more than 32,000 terminal bronchioles total.1 The main defense system within the airways is the mucociliary escalator, or mucous blanket, a combination of mucus and cilia. The mucus, which floats atop the cilia (Fig. 17-7), traps foreign particles. Ciliary movement then propels the entire mucous blanket and any trapped particles upward toward the pharynx at an average speed of 1 mm/min in the smaller bronchioles and 12 mm/min in the larger airways and trachea. After the pharynx is reached, the mucus is swallowed or cleared. The submucous glands of the airways produce approximately 100 mL of mucus per day, with all but about 10 mL resorbed through the bronchial lining. The mucociliary escalator is so efficient that almost no particles larger than 3 microns reach the alveoli.8 The cough reflex is another protective mechanism in the lungs. Excessive amounts of foreign particles in the trachea and bronchi can initiate the cough reflex. Once initiated, the rapid expulsion of air carries away any foreign particles with it.9 Each terminal bronchiole gives rise to two respiratory bronchioles, with each branching two to four more times.2 The respiratory bronchioles form the transition zone of the lungs, acting as conducting airways and gas exchange units. While air is moving through them, alveolar outpouchings on their surfaces allow gas exchange to take place (see Fig. 17-6).1 Each respiratory bronchiole gives rise to several alveolar ducts, which terminate in clusters of 10 to 16 alveoli (see Fig. 17-6). Each terminal respiratory unit contains approximately 100 alveolar ducts and 2000 alveoli.2 The alveolus is the primary site of gas exchange and the end point in the respiratory tract. Approximately 300 million alveoli are in the two lungs. The alveoli are composed of several types of cells, including type I and II alveolar epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages.1,3 Type I alveolar epithelial cells comprise approximately 90% of the total alveolar surface within the lungs (Fig. 17-8). They are the chief structural cells of the alveolar wall and play a major role in the maintenance of the gas-blood barrier and gas exchange. Type I cells are extremely susceptible to injury and become inflamed when exposed to inhaled toxins.1 A variety of collateral air passages are located within the lower regions of the lungs. Within the walls of the type I cells are the pores of Kohn (Fig. 17-9), which allow collateral movement of air between alveoli. The canals of Lambert are collateral air pathways that exist between the alveoli and the respiratory and terminal bronchioles. They are of particular benefit when a respiratory bronchiole is blocked or collapsed, because they allow gas to pass into alveoli distal to the blockage. Collateral air passages are of significant benefit in any pathologic condition of the lung that results in obstruction of airflow into a portion of the lungs. However, these pores and canals also allow the movement of microorganisms through lung tissue.1,2 Type II alveolar epithelial cells occur in much greater numbers than type I cells, but because of their minute size, they comprise a smaller portion of the total alveolar wall. After injury to the alveolar wall, type II cells rapidly divide to line the surface; later, they transform into type I cells. The most important function of the type II cells is their ability to produce, store, and secrete pulmonary surfactant (Fig. 17-10).1,3 Surfactant is a phospholipid composed of fatty acids bound to lecithin. Like other surfactants, such as detergents and soaps, pulmonary surfactant functions to lower surface tension of the alveoli. Whereas with detergents and soaps this decrease in surface tension cleans clothes, within the lungs, it stabilizes the alveoli, increases lung compliance, and eases the work of breathing. When pulmonary disease disrupts the normal synthesis and storage of surfactant, the lungs become less compliant, and the work of breathing increases. Severe loss of surfactant results in alveolar instability and collapse and impairment of gas exchange.10

Pulmonary Anatomy and Physiology

Thorax

Thoracic Cage

These structures form a protective and expandable cage around the lungs and heart. A, Anterior view. B, Posterior view. (Adapted from Thompson JM, Wilson SF. Health assessment for nursing practice. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996. In Patton KT, Thibodeau GA, eds. Anatomy and Physiology. 8th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2013.)

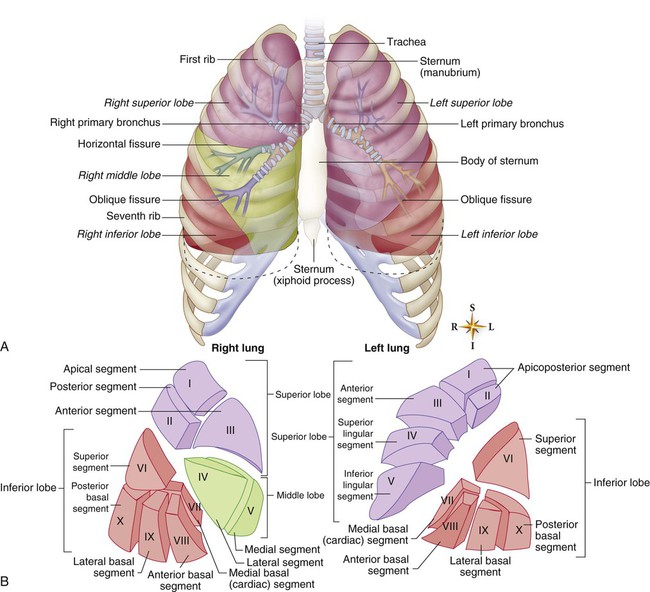

Lungs

Lobes and Segments

Mediastinum

Pleura

Intrapleural Pressure

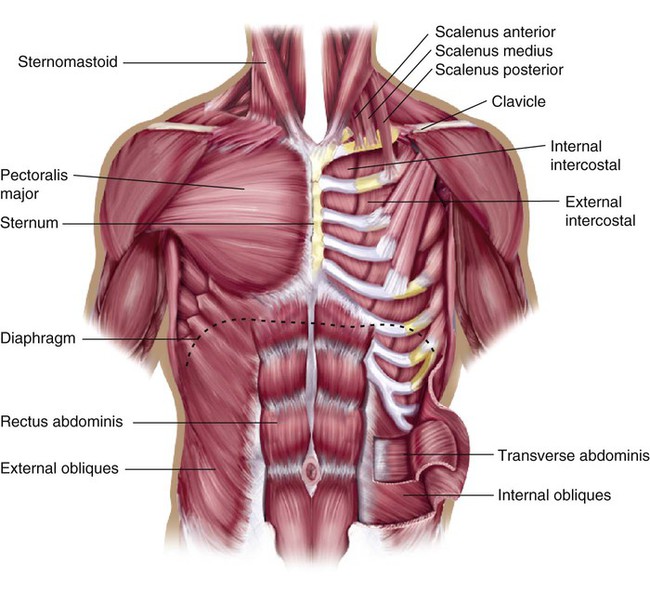

Muscles of Ventilation

Inhalation

Exhalation

Accessory Muscles

Conducting Airways

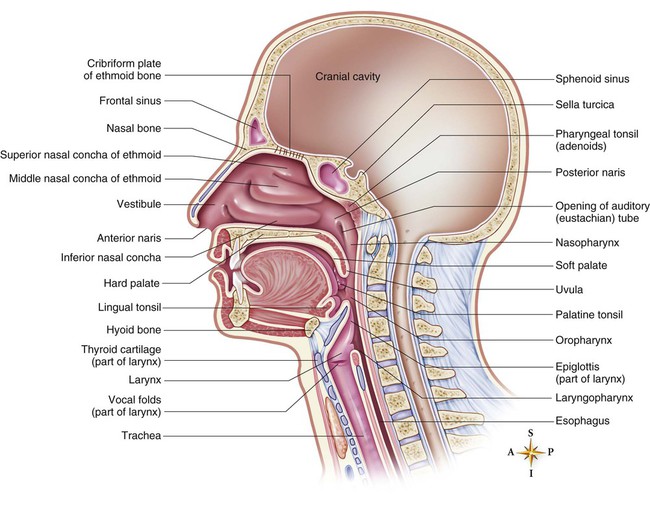

Upper Airways

In this midsagittal section through the upper respiratory tract, the nasal septum has been removed to reveal the turbinates (nasal conchae) of the lateral wall of the nasal cavity. The three divisions of the pharynx (nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx) are also visible. (From Patton KT, Thibodeau GA, eds. Anatomy and Physiology. 8th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2013.)

Epiglottis

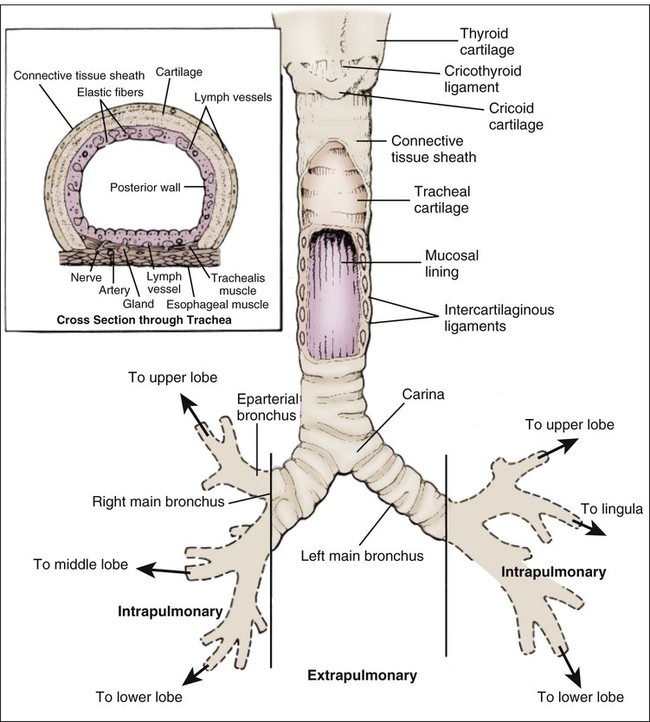

Trachea

Bronchial Tree

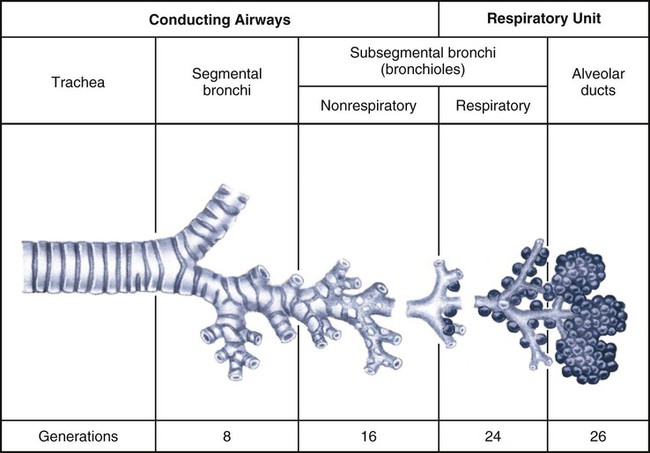

Bronchi

Bronchioles

Defense System

Respiratory Airways

Respiratory Bronchioles

Alveoli

Type I Alveolar Epithelial Cells

Collateral Air Passages.

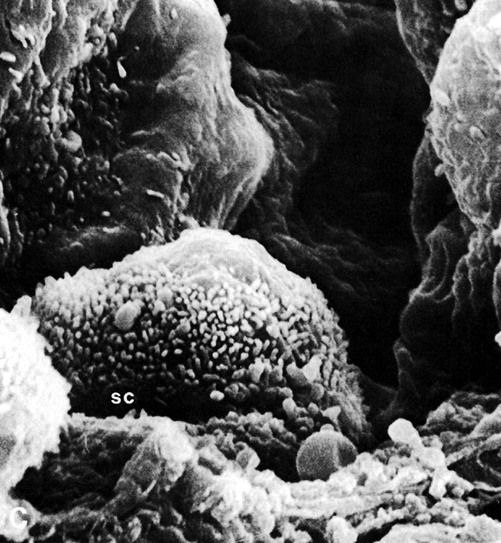

Type II Alveolar Epithelial Cells

Notice the presence of brush microvilli on all except the bald top of the round luminal surface. Type II cells produce surfactant (scale: 1 cm of picture width = 0.85 micron). (From Martin DE. Respiratory Anatomy and Physiology. St. Louis: Mosby; 1988.)

Surfactant.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pulmonary Anatomy and Physiology

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access