Chapter Seven. Public health and health promotion – frameworks for practice

Dianne Watkins

The emergence of health promotion and the new public health movement

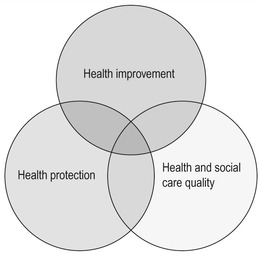

The term health promotion and its underlying theory have received much interest from 1978 up until the present time. Much of this has been fuelled by global policy, in particular the Alma Ata Declaration (World Health Organization (WHO) 1978), the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO 1986) and the Health for All Policies which emerged from these documents. The move from cure to prevention gained momentum during the 1990s, with policy makers, governments and subsequently healthcare providers striving to take forward health-promoting initiatives in an attempt to reduce inequalities in health and reduce the burden of preventable diseases. Some activity was under the guise of public health medicine, while other work came under the remit of health promotion. Historically there has been confusion and overlap between health promotion and public health and the lack of distinction between these terms hindered collaborative working during the latter part of the 20th century. Fortunately a unity of health promotion and public health under the overall umbrella of what was called the ‘new or modern public health movement’ emerged in the 21st century with increased clarity over roles and responsibilities. The new public health is seen to comprise three overlapping spheres of activity: health improvement, health protection and health and social care quality (Gillam et al 2007). Health promotion now fits primarily under the remit of health improvement. However, for ease of reading and understanding, the term ‘health promotion’ will be used throughout this chapter recognizing its fit under the remit of health improvement, and public health. Figure 7.1 illustrates the new public health and its various dimensions.

|

| Figure 7.1 •The domains of public health (Griffiths et al 2005). |

The overlapping spheres of health improvement, health protection and health and social care quality allow for enhancement of the health of populations to be addressed through a number of different avenues. Health improvement is seen to encompass work to tackle inequalities and the socio-economic influences on health. Its emphasis is on health promotion, promoting individual, family and community health, lifestyle education and the psychosocial aspects of health (Gillam et al 2007, Griffiths et al 2005). Health protection is concerned with the control of communicable diseases, environmental issues such as clean air and water, any threats to health imposed by war, chemical or radiation, preparation to deal with disasters and occupational health. The domain of health and social care quality seeks to address issues associated with determining the quality and efficiency of health and social care systems and organizations, the enhancement of quality standards in health and social care provision, the promotion of evidence-based practice, research, audit and evaluation, with an ultimate aim of promoting clinically effective practice (Gillam et al 2007, Griffiths et al 2005). The overlapping nature of the Venn diagram in Figure 7.1 illustrates that each dimension influences the others and there is a degree of common ground between each sphere.

This chapter will concentrate primarily on the sphere of health improvement, while recognizing the other dimensions and how they influence each other. The focus within health improvement is on ‘health promotion’, which incorporates education and the influence of socio-economic factors on health. Those working to improve health need to be aware of the effects of economic disadvantage, poverty, employment and unemployment, social class, education, housing and lifestyle on health achievement. Many of these elements are often beyond the control of the individual and will influence lifestyle choices and behaviours. The chapter now moves on to define the meaning and dimensions of health promotion.

Defining health promotion

It is acknowledged that health promotion does not sit alone as a concept, and is influenced by the disciplines of sociology, psychology, epidemiology, education, medicine and biological science, economics and statistics, to name but a few. This eclectic mixture of theories makes health promotion an interesting and challenging area, and means that those working to promote health should not do so without analysing and synthesizing how these theories fit together, how they influence practice and how they underpin the skills required to promote health effectively. Other chapters within this book make reference to some of these theories (e.g. Chapter 4). Health promotion theory is relatively new with a short history associated with its development, unlike theories associated with areas such as relativity or epidemiology. Much of the theory generation was initiated following developments in the 1970s, particularly Alma Ata (WHO 1978) and the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO 1986), as previously mentioned. It is worth examining the latter as a starting point to discussions surrounding theoretical concepts and definitions. The WHO (1986) defines health promotion as:

the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve their health. To reach a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, an individual or group must be able to identify and to realize aspirations, to satisfy needs, and to change or cope with the environment. Health is, therefore, seen as a resource for everyday life, not the objective of living. Health is a positive concept emphasizing social and personal resources, as well as physical capacities. Therefore, health promotion is not just the responsibility of the health sector, but goes beyond healthy life-styles to well-being. (WHO 1986: 1)

The Ottawa Charter determines that this philosophy may be achieved through the areas of advocacy, enablement and mediation and is linked to specific areas associated with building healthy public policy, re-orientating health services, creating supportive environments, strengthening community action and helping people develop their personal skills. These broad areas illustrate the enormous task associated with health promotion and its emergence into a full public health framework (as previously outlined) allows for these issues to be addressed through maximum collaboration with multiple partners. For example, building public health policy and creating supportive environments may require working with governments, politicians and local councillors, environmental health departments and transport to develop local infrastructures and to address the social determinants of health. In the context of the wider public’s health, nursing plays only a small part, and the profession cannot work in isolation when working to influence the overall health of individuals, communities and populations. Other chapters within the book expand on collaboration and partnership working for health in greater detail (see Chapter 21).

One of the early definitions of health promotion was offered by Catford and Nutbeam (1984). They characterized health promotion as incorporating any activity that set out to improve or protect health and this may be based on promoting behavioural, biological, socio-economic or environmental changes. This reasoning is based on the Lalonde Report (1974), which reported on the health of Canadians, and advocated that health promotion should be based around a health field concept that included four areas; human biology, environment, lifestyle and healthcare organization. The biological dimension includes aspects of physical and mental health inclusive of hereditary factors, diseases and disabilities which adversely affect health. Environment refers to those factors which individuals may have little personal control over and are outside the human body. Much of this is related to the area of health protection mentioned earlier in the chapter such as radiation, clean water, air pollution, war, socio-economic factors, etc. Lifestyle refers to individuals making choices which may adversely affect their health, such as smoking, drug/alcohol misuse, diet, exercise patterns, etc. These are primarily seen to be within the control of the individual; however, the other dimensions of a person’s life may well influence lifestyle decisions. The fourth area of healthcare organization incorporates the quality aspects of healthcare delivery and organization and focuses on the delivery of cure and treatment. The health field concept has influenced much of the work around health promotion in the United Kingdom.

The meaning of health promotion has consistently been hampered by efforts to differentiate between health promotion and health education. One of the most recent conceptual analyses by Whitehead (2004) makes a clear distinction between these two terms. He states that health promotion is ‘the process by which the ecologically-driven socio-political determinants of health are addressed as they impact on individuals and the communities within which they interact’ (Whitehead 2004: 314).

The emphasis in this definition is on political endeavours and empowering communities to make a contribution to influencing the wider determinants and their detrimental effects on health. He describes health education as ‘an activity that seeks to inform the individual on the nature and causes of health/illness and that individual’s personal level of risk associated with their lifestyle behaviour. Health education seeks to motivate the individual to accept a process of behavioural change through directly influencing their value, belief and attitude systems, where it is deemed that the individual is particularly at risk or has already been affected by illness/disease or disability’ (Whitehead 2004: 313). This interpretation suggests that health promotion involves working at a population or community level to influence health, while health education concentrates on working with individuals to try to improve personal health and well-being.

Other authors support the notion put forward by Whitehead. For example, Tones and Tilford (2001: xiii) state that health promotion = health education × healthy public policy. The personal opinion of the author of this chapter is that health promotion is an umbrella term that involves all activity that works to enhance health. This may involve working at a population or community level to improve social/environmental issues or develop healthy public policy, or working with individuals in one-to-one interactions to promote health-enhancing behaviour. Dividing these activities into the two separate areas of health promotion and health education may distract nurses from considering the broader issues that can influence health. Health education has a history of ‘blaming the victim’ and nurses are still criticized for not considering the influence of environmental and social factors on health achievement (Smith et al 1999, Whitehead 2003). Authors discuss the importance of ensuring that health promotion incorporates the socio-political dimensions, as well as behavioural aspects, thus ensuring that structuralist and individualistic aspects are considered (Tones and Tilford 2001, Naidoo and Wills 2000). The following section outlines briefly the impact of socio-economic and environmental factors on health to try to promote an awareness of why these are important to consider in health promoting practice.

The influence of environmental and social factors on health achievement

There is a wealth of evidence that documents the effects of environmental and social factors on health and people’s decisions about their health and lifestyle (Acheson 1998). It is beyond the scope of this chapter to explore these determinants of health in great detail; however, an awareness of their impact is essential to be able to promote health effectively (Chapters 3 and 4 also make reference to these issues).

Environmental factors such as the geographical location of residence, natural disasters, war, famine, unsafe water, pollution, and working and living conditions can adversely affect people’s health. These can be categorized into influences that occur at a macro, meso and micro level. Macro refers to the country or regional level. Examples of influences on health at a macro level include natural disasters such as the ‘tsunami’ (December 2004) or the tropical cyclone which hit Burma (May 2008); war and its effects such as the Somali civil war; political unrest, for example Robert Mugabe’s campaign of terror against the people of Zimbabwe where people were brutally attacked and even murdered if they did not comply with his views and voted against him. The meso level refers to workplace, communities, schools, etc. which can influence health. Examples of adverse influences at a meso level include occupational hazards, for example excessive noise, operating complex machinery, labouring, shift patterns and their influence on health (Cooper and Starbuck 2005); the job one engages in makes a difference to health and is a known determinant that affects health achievement (Naidoo and Wills 2000) (for further information relating to the effects of work on health see Chapter 8). Geographical location of residence, the neighbourhood and community in which people live also influences health (Drever and Whitehead 1997, Wilkinson and Marmot 2003). It is well documented in the United Kingdom that there is a north–south divide in the country’s health (Wilkinson and Marmot 2003) and examples of this have been demonstrated in Chapter 3. At a micro level environmental influences on health relate to peer group and family norms and values influencing health and health choices (Tones and Tilford 2001). People’s lifestyle choices may be dependent on environmental constraints and this should be considered when promoting health. Part of the role of the nurse working in a public health role should be to work to address environmental issues where possible, such as campaigning for safer roads and transport, community green areas and play facilities for children, better housing, workplace conditions or the school as a healthy environment for children.

Poverty and its influence on health and health choices have been repeatedly reported in numerous studies and there is a direct correlation between social class and health (Acheson 1998, Department of Health 2005). Before looking at the evidence base on the differences in health between social classes, it is worth identifying how social class is differentiated. The following outlines the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (Office for National Statistics 2002). It supersedes the Registrar General’s Social Class classification:

1. Higher managerial and professional occupations

1.1. Large employers and higher managerial occupations

1.2. Higher professional occupations

2. Lower managerial and professional occupations

3. Intermediate occupations

4. Small employers and own account workers

5. Lower supervisory and technical occupations

6. Semi-routine occupations

7. Routine occupations

8. Never worked and long-term unemployed.

It is important to note that many of the studies which provide the evidence base for the differences in health between social groups are based on the old Registrar General Classification of Social Classes I–V: Social Class I – professionals; Social Class II – managerial and technical; Social Class III – skilled manual and non-manual (white collar) workers; Social Class IV – semi-skilled workers; and Social Class V – the unskilled labourer. The social class of a family is based on the occupation of the head of the household and does not consider other workers within the family who may make a contribution to the household income. This is a limitation of taking only social class as an indicator of health. Wilkinson and Marmot (2003) have investigated other materialistic variables other than social class, such as possession of a car or being a house owner. In all circumstances it has been proven that more affluent people generally experience better health (Acheson 1998, Wilkinson and Marmot 2003). Material disadvantage makes a difference to health and social class provides some indication of ways of life and income experienced. The following outlines the original theories presented for the inequalities in health that exist between social groups.

Reasons for inequalities in health between social groups

(Adapted from Acheson 1998, Townsend and Davidson 1982.)

• Artefact.

• Natural and social selection.

• Cultural/behavioural.

• Materialist/structuralist.

Artefact and the natural and social selection explanation

This theory originally suggested that inequalities in health across the social strata were artificial and flawed and related to the way in which health was measured and defined. It argues that the data used to define differences in health between social groups present only ‘ill health’ and ‘death’ and do not present measures of health. The theory argues that while it is accepted that comparing the life chances of individuals in the highest and lowest strata of society leads to the finding that better health and longevity appear to be enjoyed by the wealthy, the comparison of life chances, between rich and poor, over time, is flawed. It is contended that this widening gap identified by ‘The Black Report’ and reinforced by others (Acheson 1998) is an artefact in that statistics have been collected over time and so do not reflect true difference. The artefact theory asserts that, in a society such as the UK, there has been great social upheaval over the past 100 years and that the social class structure itself is in a constant state of flux. It maintains that Social Class V in more recent times, for example, has little or no similarities to Social Class V, as defined, in bygone eras. The massive growth seen in the middle classes in post-war Britain and the rapid expansion in opportunities for higher education mean that this group has changed beyond recognition, making comparison over time impossible. The general trend in the gentrification of society means that the lower social classes ultimately become a refuge for the old, weak and disabled living on the margins of society. Within these groups of people there will be a greater chance of death and ill health sooner or later and this explains the natural and social selection theory, inevitably leading to the poor health statistics found in the lowest social classes.

Cultural/behavioural explanations

This theory suggests that people in lower social classes engage in more adverse lifestyle behaviour, that their behaviour is irresponsible and their ill health is a product of this. In essence this theory blames people for their own ill health. It also suggests that there is a certain subculture present in different social groups which is either harmful or beneficial to health.

There are several theories which try to explain why people indulge in adverse lifestyles that affect their health and it is beyond the scope of this chapter to present the known evidence base on the links between smoking and health, drug misuse and health, poor dietary patterns and health, obesity and health, lack of exercise and health, stress and health, to name but a few. Tones and Tilford (2001: 27) suggest adverse lifestyles may be down to ‘learned helplessness’ resulting from chronic exposure to debilitating social conditions and lack of money. This suggests that people from lower social groups living in poverty may well search out lifestyle behaviours that help them to cope with the difficulties they continually encounter in their life. For example, there is evidence to suggest that women from lower social classes smoke to help them cope with their life in poverty (Graham 2000).

Other authors suggest there may be differences in the social norms, values and beliefs across the social class strata, with people from middle classes feeling they have more control over their health than those from lower social classes who do not believe they influence their own health. These beliefs are passed from generation to generation and hence the cycle of poverty and feeling helpless is perpetuated (Naidoo and Wills 2000).

There is a theory that postulates people influence and have control over their lifestyle, whoever they are. This ‘victim blaming approach’ blames people for their own ill health and proposes that people from all social classes are in control of their own lifestyle. There is contradictory evidence to dispute this theory based on the work of Acheson (1998).

Materialist/structuralist explanation

This theory suggests that ill health among the poorest is attributable to social and economic factors. For example, those with less money experience material disadvantage in relation to housing, diet, occupational hazards, transport, access to healthcare, etc. These factors adversely influence their health.

Some postulate that the unequal burden of illness and death experienced by the poorest in society is directly related to the distribution of wealth and resources. It is argued that due to poverty, people are forced to live in poor, cramped housing conditions. It is often those who live in poverty who are forced by their life circumstances to leave school early and consequently, due to a lack of education, are forced to take up low-paid, often hazardous employment. This lack of education and money can impact on lifestyle, life choices, material possessions such as adequate transport, house ownership and access to healthcare. In relation to health provision for the poor, the South Wales general practitioner Julian Tudor Hart made the observation that those with the greatest need often received the worst service, an observation that is now universally known as the inverse care law (Tudor Hart 1971).

This brief overview of inequalities in health is further expanded upon with examples from the Caerphilly Health and Social Needs Study in Chapter 3 and in Chapter 4 on epidemiology and its application to practice. It is suffice to conclude in this chapter that social class continues to be used as an indicator of health status and it is recognized that people from higher social classes experience better health compared to those from lower social classes (Acheson 1998, Department of Health 2005).

It is crucial for nurses to understand the impact of factors such as unemployment, social exclusion, poverty, gender, stress, violence, inadequate housing and workplace hazards on health and to consider how their roles can contribute to reducing inequalities in health. The Canadian Nurse Association (2005) states that nurses, through a re-orientation of their existing practice, can influence determinants that affect individual and population health through, for example:

• comprehending how determinants of health, for example age, gender, ethnicity, income, housing and social support, affect individual and population health and well-being

• incorporating questioning on the wider determinants that affect health when undertaking health assessments

• collaborating with partner health and social care agencies, e.g. citizens’ advice bureaux, advocacy groups, housing departments, to raise awareness of need and mobilize resources

• working to inform and empower individuals, groups or communities to express felt needs

• being knowledgeable on the availability of local and national resources

• advocating for universal access to basic health programmes such as dental care

• campaigning for health improvement initiatives such as ending the physical punishment of children.

Assessing health needs using a social model of health recognizes the negative impact of deprivation and disadvantage on health. This can assist nurses in their public health role by alerting them to factors that could influence individual and family health (Watkins 2003).

To conclude this part of the chapter, it is important to recognize and understand the determinants of health and their influence on health and health choices and there is now uncontested evidence that there are gross inequalities in health between the rich and the poor, an issue now recognized by governments in the United Kingdom. The following health promotion approaches and models presented link back to the theory that has been covered in this section.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access