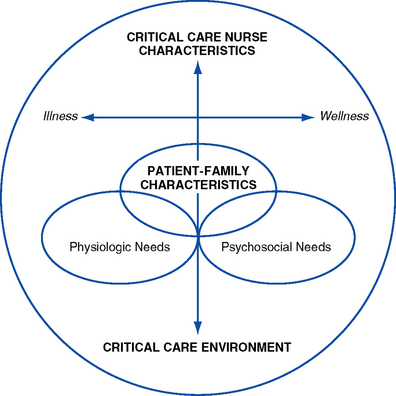

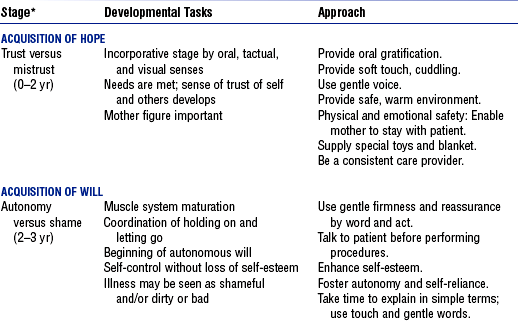

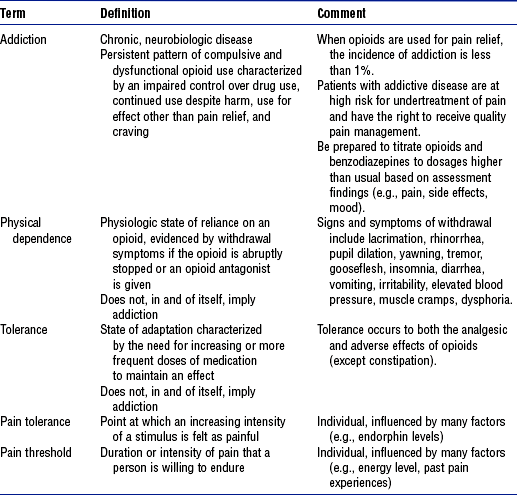

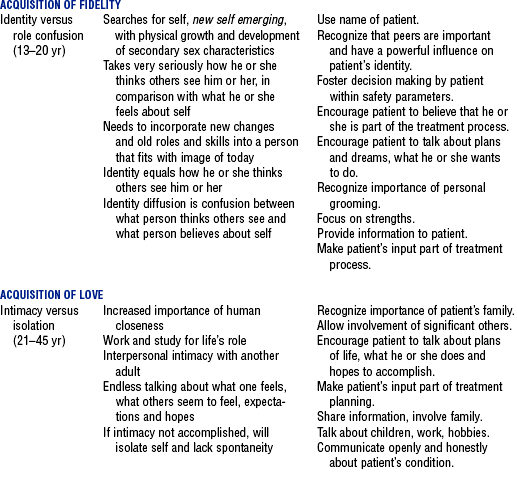

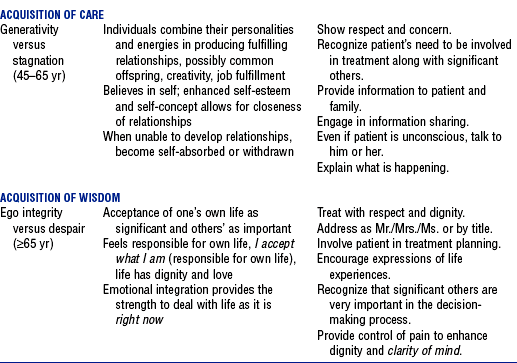

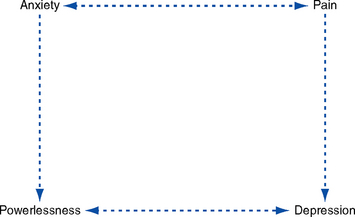

CHAPTER 10 ELIZABETH A. HENNEMAN, RN, PhD, CCNS and JAN MARIE BELDEN, MSN, APRN, BC, FNP (Contributor for content related to pain) 1. Scope of critical care nursing practice a. “The scope of practice for acute and critical care nursing is defined by the dynamic interaction of the acutely and critically ill patient, the acute or critical care nurse and the health care environment” (American Association of Critical-Care Nurses [AACN], 2000, p. 2) (Figure 10-1) b. Critical illness is a crisis for both the patient and family members. This crisis situation can present numerous, oftentimes complex psychosocial issues and problems that require the expertise of the critical care nurse working collaboratively with the multidisciplinary team. The crisis of a critical illness may be superimposed on other chronic stressors (e.g., addiction). c. Needs or characteristics of the patient and family influence and drive the characteristics or competencies of the critical care nurse (AACN, 2003) d. Challenges of meeting psychosocial needs i. Other conflicting priorities such as addressing the physiologic instability of the patient may preclude or inhibit nurses from meeting the psychosocial needs of the patient and family ii. Psychosocial needs often involve family members (an aspect unique to psychosocial needs in contrast to physiologic needs); for example, issues such as grief and loss, and powerlessness may pertain more to the family than to the patient in some situations (e.g., brain-dead patient) iii. Value systems in critical care units often emphasize performing nursing tasks over attending to the psychosocial needs of the patient and family iv. Meeting psychosocial needs demands a coordinated, multidisciplinary approach to care v. Critical care environment is often a barrier to effectively meeting psychosocial needs vi. Growing evidence supports an interrelationship between psychosocial and physiologic problems (e.g., stress and immunity) i. Critically ill patients share some common, predicable psychosocial needs (e.g., the need for reassurance and support) ii. Specific patient psychosocial needs vary depending on patient and family characteristics and the patient’s status on the health-to-illness continuum iii. The more compromised the patient, the more complex the patient’s needs iv. Critically ill patients’ psychosocial needs are based on patient characteristics, including resiliency, vulnerability, stability, complexity, resource availability, participation in care and decision making, and the predictability of the illness (AACN, 2003; Hardin and Kaplow, 2005) v. Patient characteristics and needs influence family members’ needs and psychosocial issues (a) Traditional: “A group of two or more people who reside together and who are related by birth, marriage, or adoption” (US Bureau of the Census, 2000) (b) Contemporary: “Group of people who love and care for each other” (Seligmann, 1990) ii. Families of critically ill patients share a variety of predictable psychosocial needs iii. Specific psychosocial needs of family members vary depending on patient characteristics, family characteristics, and the patient’s status on the health-to-illness continuum (e.g., cultural diversity issues) iv. Predicable needs of family members of critically ill patients include the following: i. Critical care nurse characteristics influence the extent to which patient and family psychosocial needs are met ii. Continuum of nursing characteristics includes clinical judgment, advocacy and moral agency, caring practices, collaboration, systems thinking, response to diversity, clinical inquiry, and facilitation of learning (Hardin and Kaplow, 2005) i. Members of the critical care team include the nurse, physician, respiratory therapist, social worker, clergy, physical therapist, occupational and speech therapist, others as needed ii. Psychosocial needs of the patient and family are met through the collaborative efforts of a multidisciplinary team; each member brings a unique perspective and specific expertise to the shared plan of care and patient goals i. Critical care environment (interaction among elements—hence complexity) i. Patients and family members come to critical care units at all phases of the life cycle ii. Growth and development of the patient and family members influence psychosocial needs, response to critical illness, and behaviors (e.g., body image changes may present serious psychologic stressors to young adults) iii. Erikson’s eight stages of the life cycle: See Table 10-1 i. Maslow categorized needs in terms of a hierarchy ii. Basic needs must be satisfied before higher-level needs can be met iii. Needs change throughout the life cycle iv. Critical illness may require refocusing on the achievement of basic needs (a) Derived from general system theory—a method of viewing systems that are composed of related parts that interact together as a whole (b) Can be used by critical care nurses to understand family cultural patterns and dynamics, including communication patterns, power, economics, and interaction. Also helps give insight into dysfunctional family relationships (Satir, 1967). (a) Groups of individuals bonded together by their interests (b) Community whose members nurture and support one another (c) Members have a set of rules, roles, power structure, forms of communication, and styles of problem solving that allow tasks to be accomplished effectively (d) Critical illness alters rules, roles, power, and so on, in the family, which creates stress and the need for adaptation to a new environment and situation i. Can directly affect the ability to meet a patient’s needs, including the need for rest and sleep (e.g., lack of doors on patient rooms, fluorescent overbed lighting, etc.). ii. Staff awareness and behaviors also can have a profound effect on modifying environmental influences that affect the patient. iii. Unusual patterns of light and noise, together with the constant activity of a critical care unit, alter the patient’s biologic rhythms and may negatively affect patient outcomes (Jastremski and Harvey, 1998) iv. Environmental factors may lead to sensory overstimulation or sensory deprivation (a) Noise: Sources of noise include staff conversations, alarms, and equipment. Critically ill patients have reported the sound of human voices outside the room to be the most disturbing sound (Topf, Bookman, and Armand, 1996). Adverse effects of noise include increased adrenaline levels, diminished immune function, and decreased pain tolerance (Grumet, 1993; Pope, 1995). v. Strategies for creating a healing environment: See Box 10-1 i. Definition: Condition that exists in an organism when it encounters stimuli (Selye, 1974) ii. Critical illness is a stressful situation. Directed interventions by the nurse can lessen stress and/or the impact of stress on the patient and family. Nursing presence and the anticipation of patient needs have been reported to be associated with less stressful critical care experiences (Holland, Cason, and Prater, 1997; Pettigrew, 1990). iii. Selye (1974) identified two types of stress (a) Eustress: Condition that exists in an organism when it meets with nonthreatening stimuli (b) Distress: Condition that exists in an organism when it meets with noxious stimuli iv. Common psychologic stressors for critically ill patients and their families (a) Noxious psychosocial stimuli can overwhelm the body’s compensatory ability to maintain homeostasis and can elicit a stress response (b) Major neural response to a stressful stimulus is activation of the sympathetic nervous system (c) Relationship between psychologic stress and health: Psychoneuroimmunologic research has identified a relationship between stress and immune function (i.e., an increased stress response is associated with decreased immunity) (Caine, 2003) i. Identify preexisting psychiatric, psychologic, and social problems ii. Identify preillness coping mechanisms iii. Identify sources of support (e.g., family, friends, spiritual support, pets) iv. Identify patient proxy, living will, durable power of attorney, and so on b. Family history: Family assessment data obtained on admission or as soon as possible i. Health care proxy or family spokesperson ii. Contact information (e.g., home and cell phone numbers, pager numbers) iii. Diversity issues (culture, language, etc.) that affect the patient and family vi. Support systems (family, friends, church group, other spiritual support) vii. Special family needs (e.g., young children, handicaps, etc.) viii. Family concerns regarding this hospitalization ix. Best time for family to visit the patient x. Preferred method of meeting and communicating with intensive care unit (ICU) team members (e.g., participation in scheduled ICU rounds, scheduled evening meetings, phone calls) 2. Nursing examination of patient b. Cognitive assessment (e.g., ability to concentrate, level of judgment, presence of confusion) c. Behavioral assessment (sleep patterns, level of agitation, interaction with family and staff) d. Review of findings from other diagnostic studies (e.g., computed tomographic [CT] scan, electroencephalogram [EEG], etc.) 3. Appraisal of patient characteristics: Almost all patients with a critical illness experience some psychosocial issues during the course of their illness. However, each patient and family is unique and brings a unique set of characteristics to the care situation (Hardin and Kaplow, 2005). Examples of characteristics of patients and family that the nurses need to assess include the following: i. Level 1—Minimally resilient: A 52-year-old divorced woman who has attempted suicide via drug overdose on three previous occasions is admitted with a nonlethal self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head ii. Level 3—Moderately resilient: A 23-year-old man with a 9-year history of “problem drinking,” stabilized after chest trauma suffered in an alcohol-related automobile accident, is being prepared for transfer to a military hospital where he will receive extended treatment for alcohol abuse iii. Level 5—Highly resilient: A healthy 21-year-old female college student with a 3.9 grade point average comes to the emergency department exhibiting multiple abrasions and unruly, belligerent, and delirious behavior after attending her first “spring breakout celebration,” which included drinking, some drug experimenting, and falling off the roof of a moving car i. Level 1—Highly vulnerable: A malnourished 9-year-old child who has been a victim of child abuse since birth is recovering from his most recent “fall down the stairs” and is scheduled for discharge home the next day ii. Level 3—Moderately vulnerable: An extremely overweight 37-year-old woman admits to feeling “even more depressed” following her unsuccessful suicide attempt. Numerous diets, pills, and plans have not worked, and her primary physician relates that she does not meet the criteria for surgical treatment of morbid obesity. iii. Level 5—Minimally vulnerable: A 44-year-old single father, admitted for monitoring overnight subsequent to an automobile crash in which he was cited for aggressive driving, relates that since his recent divorce, he occasionally has had episodes when his anger quickly escalates to violent behaviors. He fears “taking it out” on his two sons. i. Level 1—Minimally stable: A 65-year-old woman develops acute respiratory distress syndrome following the ingestion of an alkali solution during an attempted suicide ii. Level 3—Moderately stable: A 50-year-old male with a history of drinking four beers a day is admitted to the ICU for an initial episode of gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to a duodenal ulcer. He is receiving benzodiazepines to prevent delirium tremens from acute alcohol withdrawal. iii. Level 5—Highly stable: A 25-year-old female is admitted to the ICU from the emergency department, to which she was brought by friends who could not wake her after a night of heavy drinking. She is now awake and alert. i. Level 1—Highly complex: An 89-year-old man is experiencing liver failure secondary to the ingestion of 200 acetaminophen tablets following the death of his wife. Patient has multiple medical problems, including lung cancer. He stated in his suicide note that he “is tired” and wants to be with his wife. Family is adamant that everything be done to save his life. ii. Level 3—Moderately complex: A 60-year-old patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis develops acute respiratory failure while in the ICU. Patient has already stated he does not desire mechanical ventilation to prolong life. Family is supportive of the patient’s wishes. iii. Level 5—Minimally complex: A 50-year-old woman in the ICU for the management of gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory use develops delirium after receiving sedatives i. Level 1—Few resources: A 40-year-old homeless man is admitted to the ICU after attempted suicide by gunshot to the head. No patient identification is available. ii. Level 3—Moderate resources: An 83-year-old woman is admitted from a local nursing home to the ICU with possible urosepsis. Patient’s family has been paying out of pocket for the nursing home but says “the money is almost gone.” iii. Level 5—Many resources: A 60-year-old computer executive develops delirium tremens 4 days after undergoing elective hip surgery. Family is very supportive and confident the patient would be concerned if he realized how his drinking (three to four glasses of wine per day) had affected him. Patient has excellent insurance coverage for both inpatient care and outpatient substance abuse treatment. i. Level 1—No participation: An 85-year-old male patient underwent a complicated aortic aneurysm repair 3 days earlier. Patient has a 10-year history of dementia and is now experiencing delirium. He is intubated and unable to communicate with the staff. ii. Level 3—Moderate level of participation: A 35-year-old man, who sustained a head injury after falling out of a tree while intoxicated, is now regaining consciousness and is asking for some water iii. Level 5—Full participation: A 70-year-old man is admitted to the ICU following extensive abdominal surgery. He asks the nurse for more pain medication so that he can “sit up more and take some deep breaths” like his preoperative instructions directed. g. Participation in decision making i. Level 1—No participation: The mother of an 18-year-old brain-dead patient collapses when approached about organ donation. She asks the patient’s doctor to make all the necessary decisions. ii. Level 3—Moderate level of participation: The wife of a 67-year-old man who requires a tracheostomy for long-term airway management following a suicide attempt requests multiple consults from other pulmonary services iii. Level 5—Full participation: A 65-year-old patient with cancer and chronic pain asks to be removed from the ventilator and be “allowed to die with dignity” i. Level 1—Not predictable: A 75-year-old woman with ovarian cancer is admitted after ingesting one-half of a bottle of acetaminophen to “stop the pain” ii. Level 3—Moderately predictable: A 60-year-old patent with acute respiratory failure develops delirium secondary to a combination of hypoxemia and electrolyte imbalances iii. Level 5—Highly predictable: A 20-year-old patient is admitted with altered consciousness after drinking at a college fraternity party 1. Interdependence—Many of the psychosocial issues and concerns of the critically ill patient are interdependent. For example, inadequately managed pain may lead to feelings of powerlessness, anxiety, and depression that, in turn, heighten the patient’s perception of pain (Figure 10-2). i. Perceived lack of control over the outcome of a specific situation. The ability of an event to engender a sense of powerlessness is influenced by the individual’s self-esteem and self-concept and where the individual is in the life cycle. ii. Critically ill patients lose their ability to control even the most basic of functions, including the ability to communicate, to breath on their own, and to control bladder and bowel function. Depending on the philosophy and organization of the critical care environment, they may also lose the ability to participate in decision making about their own health care and future. i. Patient communicates needs and wishes verbally or nonverbally ii. Patient (and family as appropriate) participates in decision making regarding the plan of care iii. Patient and family members do not demonstrate signs of dysfunction associated with powerlessness, such as the following: iv. Patient participates in decision making regarding daily care activities (e.g., timing of bath, sleep, visiting hours) c. Collaborating professionals on health care team i. Promote patient-nurse communication (a) This intervention presents significant challenges, particularly if the patient is intubated or speaks a language other than English (or the predominant language at the facility) (b) Methods of communication should be based on patient preferences and abilities. Common communication techniques for use with intubated patients include lip reading, picture or alphabet boards, pen or pencil and paper, and computer. (c) Utilize available interpreter services for non–English speaking patients and family members (d) Enlist help from family members and volunteers in the communication process ii. Involve the patient and family in the care planning process and decision making (a) Ask the patient (or health care proxy) what level of involvement he or she would like in the care planning process (b) Encourage the patient and family members to keep a record of questions and concerns (c) Provide the patient, proxy, or a family member with daily (or more frequent) updates regarding the patient’s status and care plan iii. Encourage the patient and family members to meet with spiritual support persons if they would find this helpful iv. Prepare the patient for procedures: Explain what will be happening, when it will happen, and how the patient will be affected e. Evaluation of patient care: Patient and family are active participants in care planning and delivery (to the extent possible) a. Description of problem: Sleep deprivation in the critically ill patient involves a decrease in the amount, consistency, and/or quality of sleep that occurs in a 24-hour period. Sleep fragmentation occurs when the patient fails to complete a 90-minute average sleep cycle that includes both rapid eye movement and non–rapid eye movement sleep (Gawlinski and Hamwi, 1999). i. Patient has at least two 90-minute periods of sleep in a 24-hour period ii. Patient states that he or she feels rested iii. Patient does not demonstrate signs and symptoms of sleep deprivation, including the following: c. Collaborating professionals on health care team i. Attempt to provide at least two 90-minute periods of uninterrupted sleep in a 24-hour period ii. Cluster activities so that the patient is allowed periods of rest iii. Prioritize activities to allow a stable patient to have periods without unnecessary, frequent assessments iv. Decrease the noise level to promote sleep v. Decrease overhead lighting to promote sleep vi. Provide adequate pain relief vii. Teach the patient and family relaxation techniques to promote rest and sleep viii. Administer pharmacologic agents as needed to promote sleep (e.g., benzodiazepines, diphenhydramine). Note: Long-term use of benzodiazepines can abolish stage IV sleep. ix. Consult with a pharmacist regarding the best drug choices for promoting sleep, particularly for high-risk populations such as the elderly a. Description of problem: The grief reaction is the emotional response to a loss in which something valued is changed or altered so that it no longer has its previously valued traits (Gawlinski and Hamwi, 1999) i. Grief can be experienced during a critical illness by both the patient and family members ii. Grief may result from loss (or potential loss) of health, body image, role, and financial security iii. Family members experience grief related to a patient’s death or in anticipation of death or potential death iv. Degree of grief experienced is related to the meaning of the loss to the individual, the adequacy of coping responses, and the availability of support systems v. Expressions of grief have wide variation and are culturally determined i. Patient and family express feelings of grief and loss (if they choose) ii. Patient and family are able to state the prognosis and current plan of care c. Collaborating professionals on health care team i. Appreciate cultural variation in expressions of grief ii. Allow the patient and family members to express grief in their own way iii. Provide privacy for family members and patients iv. Provide ongoing, honest information to the patient and family regarding the patient’s illness and expected recovery v. Provide the patient and family with teaching regarding the normal grief response e. Evaluation of patient care: Patient and family express grief in a culturally appropriate way 1. Definition: Anxiety is the apprehensive anticipation of future danger or misfortune accompanied by a feeling of dysphoria or somatic symptoms of tension. Focus of anticipated danger may be internal or external (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). 2. Etiology and risk factors: Results from multiple sources in the ICU, including the following: a. Unstable physiologic status (e.g., hypoxemia with shortness of breath) e. Separation from family and support system f. Underlying psychiatric disorder (including panic disorders, phobias, and posttraumatic stress disorder) 3. Signs and symptoms: See Box 10-2

Psychosocial Aspects of Critical Care

SYSTEMWIDE ELEMENTS

Patient and Family Psychosocial Assessment

Psychosocial Care Issues

SPECIFIC PATIENT HEALTH PROBLEMS

Psychosocial Aspects of Critical Care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access