Chapter 20 Psychiatric barriers and the international AIDS epidemic

Introduction

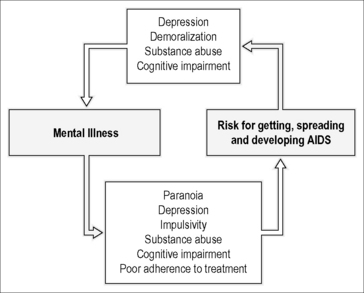

The analysis of causation and intervention in the HIV/AIDS epidemic has relied on the classic epidemiologic triad of host, agent, and environmental factors. Yet the HIV/AIDS epidemic differs from earlier pandemics in the sense that behavior is the principal vector of its spread. HIV infection is propagated by behaviors that involve intimate physical contact or exposure to blood or body secretions. In the early years of the epidemic the identified vulnerable host groups were homosexuals, heroin addicts, Haitians, and hemophiliacs (the 4-H group), which pointed to the specific behaviors that served as vectors for the viral agent. It is now recognized, especially in high-income countries, that psychiatric disability has facilitated the spread of this virus [1]. Nearly 30 years later health promotional efforts in high-income countries has slowed the epidemic considerably, in terms of overall prevalence, but transmission has continued apace among subgroups who are unable to modify their behavior without active assistance. It has become clear that psychiatric disorders, besides their role in the spread of the virus through the risk behaviors that they provoke or promote, also impact outcomes adversely by undermining help seeking and treatment adherence (Fig. 20.1). HIV/AIDS is also associated with secondary psychiatric states, such as depression, anxiety, mania, delirium, cognitive impairment, and dementia [2]. Therefore the intersections of HIV/AIDS and psychiatric disorder require examination in any discussion of HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and prognosis.

It is well established that psychiatric disorders generally have adverse impacts on health awareness, health-seeking behavior, and treatment adherence. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates [3] show that neuropsychiatric disorder is highly prevalent worldwide—the 12-month prevalence (interquartile range, IQR) is 18.1–36.1% for DSM-IV disorders and 0.8–6.8% for Serious Mental Illness (i.e., a DSM-IV disorder, other than substance abuse, that causes serious disability). Furthermore, neuropsychiatric disorders are also major contributors to disability; Serious Mental Illness results in 49–184 days/year out of role, Moderate Mental Illness in 21–109, and Mild Mental Illness in 12–67 [3]. The WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme [4] has reported that depression, with lifetime prevalence of major depression or dysthymia estimated at 12.1%, is the single largest contributor to non-fatal burden of disease and is responsible for a high number of lost disability adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide. It is the fourth leading cause of disease burden (in terms of DALYs) globally and is projected to increase to the second leading cause in 2030. Suicide, an important complication of depression, is the third leading cause of death worldwide in people aged between 15 and 34 years, and the thirteenth leading cause of death for all ages combined. It also represents 1.4% of the global disease burden (in DALYs). Alcohol use disorders, schizophrenia, and dementia are also important contributors to disease burden. An estimated 24.3 million people have dementia worldwide, a figure predicted to double every 20 years, and 60% of those with dementia live in middle- or low-income countries.

Global disparities in the global HIV/AIDS situation are also substantial, despite notable progress in the prevention of new infections and expansion of treatment in the past decade. According to the latest Global Summary of the HIV and AIDS Epidemic published in 2010 [5], there has been a 19% decline in HIV-related deaths since 1999, a 25% drop in the incidence of new infections in 33 countries (22 of these in Africa), and a 26% reduction worldwide in the frequency of mother-to-child transmission. In 2009 alone, 1.2 million patients received treatment for the first time, representing an increase in the number of people receiving treatment of 30% in a single year! Still there is much work to be done. The majority of new infections (69%) still occur in sub-Saharan Africa, and also seven middle- and low-income countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia experienced a 25% increase in HIV incidence in the past decade. Today almost 50% of the 33.3 million adults and children living with HIV reside in middle- and low-income countries [5], and the reduction in mother-to-child transmission still translates to 370,000 new children with the infection who mostly reside in low-income countries. Also 35% (5.3 million) of the 15 million in need living in these countries are receiving anti-retroviral treatment.

Economically disadvantaged people have limited access to psychiatric treatment and chronic psychiatric illness contributes to this problem through the tendency to restrict and deplete economic resources and cause economic “downward drift” into poverty. Generally, psychiatric care is least available to those who will need it the most (i.e., individuals suffering severe mental illness). This applies in high- and low-income countries [6], but is probably more acute in low-income countries where public mental health services may be deficient or practically absent. Generally, the countries most severely affected by HIV have the least developed resources for HIV treatment and for mental health. The 15 million living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries have very limited access to psychiatric services. The unmet need for mental disorders and serious mental illness is high in these countries: a survey in Nigeria found that only 1.2% of individuals received any treatment in the 12 months preceding the study [7]. This problem reflects a scarcity of treatment resources: 52% of low-income countries provide community-based care, compared with 97% of high-income countries. The median number of psychiatric hospital beds reaches as low as 0.33 per 10,000 in Africa and Southeast Asia [8]. Ultimately the principal factor limiting psychiatric care in middle- and low-income countries is the scarcity of professionals. Low-income countries have a median of 0.05 psychiatrists and 0.16 psychiatric nurses per 100,000 population, whereas high-income countries have a 200-fold higher ratio of psychiatric mental health-workers to population [8]. Treatment of psychiatric disorders is further constrained by the unavailability of essential medicines in low-income countries; about a quarter of these countries do not provide any psychotropic medicines in primary-care settings and in many others supplies are insufficient or irregular [8]. Therefore, patients and families are often forced to pay for medicines. Since these costs are relatively high in low-income countries, the result is that treatment, where it exists, is unaffordable for many. It is also worth noting that over 85% of controlled trials for cost-effective treatments are conducted in high-income countries [9]. Another key factor, and one that limits prospects for progress in the development of psychiatric services, is the lack of prioritization of mental health in national health policies and of advocacy for it at the community level [10]—a problem exacerbated by misperceptions about the cost–benefits of providing these services.

Cultural values and beliefs play a substantial role in mental health care in middle- and low-income countries [7, 11, 12]. Mental illness carries a high stigma and is often attributed to religio-magical phenomena, in which the illness represents retribution meted out by ancestors or possession by evil spirits. In some countries, such as in Uganda, those who are mentally ill are excluded from employment or voting. In many others, they are excluded from full social participation in a variety of ways that limit schooling, marriage opportunities, and forming of social networks. On the other hand, there is reliance in some areas on traditional healers who are frequently included in policy initiatives and form a substantial component of the community mental health resource. In East Africa, 70–100% of individuals consult a traditional healer as first line of care [13–15]. However, utilization of traditional methods for psychiatric care is low in many places. In Nigeria, for example, less than 5% of individuals with a psychiatric illness consult a traditional healer and about the same number seek formal psychiatric care. Cultural factors are also critical in the expression of psychological distress and psychiatric disorders and to their detection during screening programs and clinical care—lack of sophistication regarding local expressions and/or reliance on standard screening instruments that have not been culturally adapted may result in failure to detect cases.

As a consequence of the low coverage of both anti-retroviral and psychiatric treatment in middle- and low-income countries, many patients who have psychological distress and/or psychiatric disorders go without anti-retroviral treatment— from either not having sought it or not being able to maintain adherence. Generally, psychological distress and social isolation are factors in seeking antiretroviral treatment and yet often go unnoticed, especially when there is no overt symptomatology [16–18]. Longitudinal studies also confirm what had already been demonstrated in high-income countries, that psychological distress and psychiatric disorders contribute to low initiation and non-adherence in young [16, 19] and older [20] individuals suffering HIV and AIDS. A newly emerged issue is the nature of relationships between aging, cognitive dysfunction (discussed below) and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Cognitive dysfunction and dementia have been associated with higher rates of non-adherence [20, 21], and reciprocity in the adverse relationship between cognition and adherence has also been demonstrated [22].

Chronic Mental Illness and HIV Infection

A subset of patients with chronic mental illnesses such as recurrent severe major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar affective disorder have been identified as constituting a high-risk population that manifests HIV risk behaviors at higher-than-average rates, but these observations have been made in high-income countries. The prevalence rate of HIV among the chronically mentally ill in the USA has been estimated to be between 4 and 20% [23–28]. Risk behaviors associated with HIV infection are also frequently observed in this population; early studies of chronically hospitalized patients in New York [29] and patients attending community mental health clinics in Melbourne, Australia [30] showed that patients with mental illness were more likely to participate in unprotected casual sex and injection drug use when compared with the general population. This observation has been replicated in other studies [31–34], cementing the observation that individuals who suffer chronic mental illness manifest higher rates of behaviors that put them at risk for HIV infection.

Besides increasing their exposure to the virus, patients with mental illnesses are impaired in their ability to adhere to the complicated medication regimens necessary to suppress viral replication and HIV disease (discussed earlier, see also Campos et al. [35] and Venkatesh et al. [36]). Successful treatment requires consistently taking at least 90% of prescribed antiretroviral medications, with faithfulness to the dosage and to the schedule. Unfortunately, adherence rates vary widely in individuals with chronic mental illness, ranging from 32 to over 80%, depending on the group and the duration over which adherence is being monitored. For example, an analysis of data from a sample of 115 patients attending a Los Angeles HIV clinic found three-day, one-week, and one-month adherence success rates (taking 95% of doses) of 58.3, 34.8, and 26.1%, respectively. Three-day adherence was strongly associated with mental health status, social support, patient–physician relationship, and experience of adverse effects [37]. Another study estimated sustained viral suppression in only 25–40% of patients [38]. In both studies, mental illness was a factor in non-adherence to treatment. Psychosocial interventions geared toward improving autonomy, self-efficacy, and community support can improve adherence and may, therefore, be useful adjuncts to psychiatric regimens in optimizing adherence. For example, a study evaluated predictors of high ART adherence (≥90%), measured by electronic drug monitors, after enrollment in a randomized controlled trial testing behavioral interventions to improve ART adherence [39]. High motivation, positive coping styles, and high levels of interpersonal support were positively associated with adherence, whereas passive belief in divine intervention was negatively associated with adherence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree