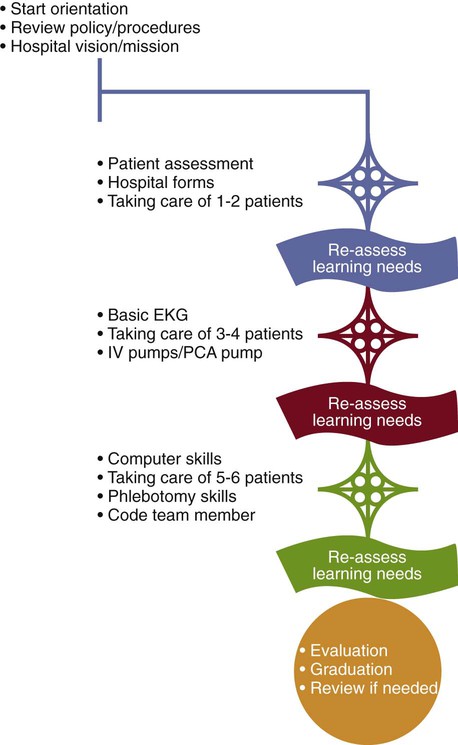

1. Discuss hospital-wide and unit-based new employee orientation. 2. Analyze the role of preceptor in nurse orientation. 3. Compare and contrast the roles of the nurse, preceptor, and human resources in orientation. 4. Analyze the progression of nursing clinical competence. 5. Review the annual mandatory competencies for patient care staff. 6. Compare and contrast the roles of manager and staff in performance appraisal. 7. Identify the steps and progression of the staff registered nurse in the clinical ladder program. 8. Discuss activities used by the nurse manager to support promotion of staff members. As the new nurse enters the workforce, it is important to realize that this is just the beginning of the professional journey. Benner (1984) posits that the nurse moves through five stages of clinical competence: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert nurse. These different levels reflect changes in three general aspects of skilled performance: 1. One is a movement from reliance on abstract principles to the use of past concrete experience as paradigms. 2. The second is a change in the learner’s perception of the demand situation, in which the situation is seen less and less as a compilation of equally relevant bits and more and more as a complete whole in which only certain parts are relevant. 3. The third is a passage from detached observation to involved performer. The performer no longer stands outside the situation but is now truly engaged in the situation. The expert performer no longer relies on an analytic principle (rule, guideline, maxim) to connect her or his understanding of the situation to an appropriate action. The expert nurse, with an enormous background of experience, now has an intuitive grasp of each situation and zeroes in on the accurate region of the problem without wasteful consideration of a large range of unfruitful, alternative diagnoses and solutions. The expert operates from a deep understanding of the total situation. The chess master, for instance, when asked why he or she made a particularly masterful move, will just say, “Because it felt right; it looked good.” The performer is no longer aware of features and rules; his or her performance becomes fluid and flexible and highly proficient. This is not to say that the expert never uses analytic tools. Highly skilled analytic ability is necessary for those situations with which the nurse has had no previous experience. Analytic tools are also necessary for those times when the expert gets a wrong grasp of the situation and then finds that events and behaviors are not occurring as expected. When alternative perspectives are not available to the clinician, the only way out of a wrong grasp of the problem is by using analytic problem solving (Benner, 1984, pp. 13–34). Box 16-1 summarizes the five stages of transition from novice to competent practitioner. It is important to realize that you do progress in professional competence as you work. Self-assessment to your current level of performance is an important function in nursing. Much of your progression will also greatly depend on the work environment. The organization provides the environment for the clinical progression of all staff, both for organizational needs and for the personal development of the nurse. Such professional work environments are evidenced in the various health care organizations that have achieved Magnet status (ANCC, 2008). The Joint Commission states that a hospital must provide the right number of competent staff to meet the needs of the patients (2007). Competent staff is a staff that is qualified and able to perform the work according to professional standards. Staffing is discussed in Chapter 19. To meet the goal of providing adequate competent staff, the hospital must carry out the following processes and activities: • The hospital provides for competent staff either through traditional employer-employee arrangements or through contractual arrangements with other entities or persons. • Orienting, training, and educating staff • The hospital provides ongoing in-service and other education and training to increase staff knowledge of specific work-related issues. • Assessing, maintaining, and improving staff competence • Ongoing, periodic competence assessment evaluates staff members’ continuing abilities to perform throughout their association with the organization. • Promoting self-development and learning. Staff is encouraged to pursue ongoing professional development goals and provide feedback about the work environment (The Joint Commission, 2007, p. 319). Orientation is a process in which initial job training and information are provided to staff. Staff orientation promotes safe and effective job performance. Some elements of orientation need to occur before staff provide care, treatment, and services. Other elements of orientation can occur when staff is providing care, treatment, and services (The Joint Commission, 2007, p. 330). All employees, regardless of level of competence, are required to attend orientation. Basic to new employee orientation is education on the organization-specific function, policies, and expectations, such as mission, vision, values, stakeholder expectations, performance improvement, basic skill evaluation, and mandatory policy review. Hospital orientations can range from 3 weeks to 6 months depending on the organization and responsibilities of the nurse. For new graduates, the orientation is often expanded to allow for mentoring to the new role. The time frame for new nurse socialization to the role, or the process of developing clinical judgment in practice, has been suggested to be as follows (Ferguson, Day, Anderson, and Rohatnsky, 2007): • Learning practice norms (orientation 4–6 months) • Developing confidence (6–12 months) • Consolidating relationships (12–18 months) The first part of orientation is usually organization specific. There is usually a hospital-wide orientation, which may include speakers such as the human resources representative, the infection control coordinator, the safety officer, the employee health coordinator, and the process improvement coordinator. This organization-specific orientation usually includes those educational topics that are considered mandatory by the accreditation agencies. These mandatory topics are usually reviewed on an annual basis in most health care institutions. This mandatory review allows for the determination of employee competency in knowledge in these content areas (Box 16-2). There then is a unit-based or nursing-based orientation. Unit-based orientations are designed by the unit educator and nurse manager to orient the new nurse to the unit, its policies, patient needs, procedures, and protocols. For example, a nurse in a cardiac unit will receive education on electrocardiogram interpretation, cardiac drugs, cardiac arrest protocols, etc. A nurse in the labor room will receive education on fetal monitoring, neonatal resuscitation, etc. Patient care assignments will be made to match the learning of orientation. A description of the growth from novice to competent practitioner is detailed in Figure 16-1. There are numerous models of nursing orientations, but most use preceptors to work with and evaluate the new employee during the orientation phase. New nurses are traditionally oriented to the professional role by “experienced” registered nurses who are knowledgeable of the “ways of nursing” in the organization. A preceptor can be defined as an experienced staff member who possesses excellent clinical skills and facilitates learning through caring, respect, compassion, understanding, nurturing, role modeling, and the excellent use of interpersonal communication (Speers, Strzyzewski, and Ziolkowski, 2004). There are varied methods of choosing preceptors and pairing them with orientees. In hospitals with clinical ladders, experienced nurses are required to serve as preceptors as part of their normal responsibilities. In other institutions, preceptors are chosen based on their competencies, while in other institutions, nurses are chosen based on availability. This last method often results in multiple preceptors for one orientee. This can result in frustration for the orientee, who may be receiving multiple messages from multiple preceptors (Hardy & Smith, 2001). Research demonstrates that proper pairing is key to the success of the preceptor program (Hardy & Smith, 2001). Proper pairing occurs with preceptors who are selected into the role based on competencies in both clinical nursing and the ability to facilitate learning (Speers et al., 2004). This model can be used to assist new employees and to reward experienced staff nurses. This model provides a means for orienting and socializing the new nurse as well as providing a mechanism to recognize exceptionally competent staff nurses (Sullivan & Decker, 2005). Box 16-3 lists various functions of the preceptor.

Providing Competent Staff

BENNER FIVE STAGES

STAGE 5: THE EXPERT

STAFF COMPETENCY

NEW EMPLOYEE ORIENTATION

MANDATORY CONTENT

UNIT-BASED CONTENT

PRECEPTOR MODEL

Providing Competent Staff

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access