CHAPTER 25 Promoting sleep

Introduction

Before reading on, reflect on the two scenarios detailed in Box 25.1. In the first, you are lying awake at home at 3 a.m. and in the second, you are awake in hospital. These two scenarios emphasise the importance that we attach to sleep. They also show how, in different situations, sleep means different things to different individuals, is affected by different environmental circumstances and the way we feel, and our ability to control how we help ourselves to sleep (Box 25.1).

Box 25.1 Reflection

Thinking about sleep

Activities

What is sleep?

We spend so much of our lives asleep that one would expect it should be easy to define sleep but, paradoxically, once we are asleep, we remember little about it. One online dictionary definition (www.answers.com/topic/sleep) suggests that sleep can be defined as:

Non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep

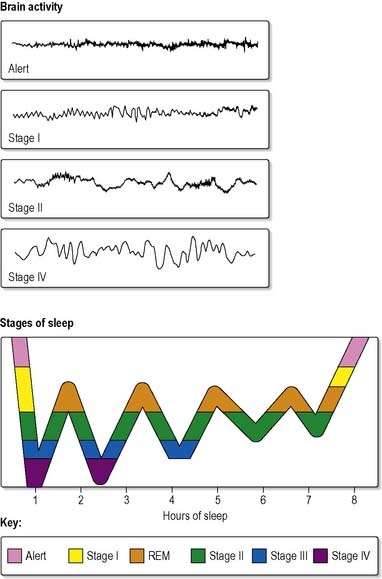

NREM sleep comprises four stages associated with differing electrical activity of the brain.

Note: Stages 3 and 4 are often considered together and termed slow wave sleep (SWS).

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep

During a night’s sleep both REM sleep and all four NREM stages may occur many times, usually in a cyclical fashion (Figure 25.1). The first part of the night tends to contain more SWS, while the latter part of the night contains a higher proportion of REM. Interestingly, even during the day people have cycles of alertness and drowsiness although they are usually unaware of these.

Precisely how and why people sleep remains the subject of much research (see Further reading, e.g. Pocock & Richards 2006 and Widmaier et al 2007).

Functions of sleep

Despite enormous research efforts, the only universally agreed reason for sleeping is to avoid being sleepy! Interpretations of research findings vary, but it is generally considered that sleep appears to have a major role in the maintenance and/or restoration of physical and cerebral functioning (Moorcroft 1995). This may include:

It has also been suggested, however, that sleep may be simply an instinctual behaviour, a genetic remnant of earlier days when immobility at night increased our chances of survival (see Further reading, Lee et al 2004).

Normal sleep

Individual requirements for sleep vary enormously. Russo (2005) highlights the differences in sleep required through the life course. For example, adults tend to need an average of 8 hours sleep each night, whereas older people generally seem to need less than this, with children and young infants needing more. Some people habitually take a nap during the day. Some are early risers, while others are more active in the evening and tend to go to bed late. Hospital routines, for instance early or late medication rounds and/or the taking of regular observations, tend to override these individual variations in behaviour, with a possible outcome of disturbed sleep patterns for some (Jarman et al 2002, Cmiel et al 2004).

Factors affecting normal sleep

Age

Changes in sleep patterns associated with age have been well documented, with neonates usually spending around 18 hours asleep in every 24, young adults sleeping for an average of 8 hours each night, and older people sleeping for 6 hours (see Further reading, Johnson 2006).

Problems such as getting to sleep or staying asleep also tend to be more common in older people (Rush & Schofield 1999); however, research reported by Klerman et al (2003) showed that although older people wake up more frequently than younger people, they do fall back to sleep at the same rate as their younger counterparts. These changes have been attributed to age-related loss of neurones and progressive fragmentation of circadian rhythmicity (Hood et al 2004). Older people also have increased amounts of wakefulness after sleep onset. Ersser et al (1999) attributed a high proportion of night-time awakenings among older people to pain and physical discomforts such as bladder distension and urinary urgency. Awareness of such problems should prompt nurses to alleviate discomfort as far as possible, to encourage regular bowel and bladder habits and ensure that optimal fluid intake is achieved by approximately 18.00 h. For those who enjoy tea or coffee, decaffeinated options should be encouraged for later in the day and evening.

Maher (2001) and Closs (2006) discuss ways of assessing and improving disrupted sleep in older people.

For older people and their carers, the knowledge that changes in sleep patterns are commonly experienced and are therefore not necessarily pathological will be reassuring. Although some caution should be exercised, lest treatable problems relating to sleep are overlooked, nurses have an important role to play in educating patients and their carers about the predictable changes that occur in sleep habits with advancing age (Box 25.2). See Further reading, Maher (2004) and Closs (2006).

Gender

Research has shown that there are some interesting differences between men and women in terms of their satisfaction with sleep. Studies report that men have more disturbances in sleep than women from early adulthood onwards (Webb 1982), frequently due to nocturnal penile tumescence occurring during REM sleep, whilst others have highlighted that women, despite sleeping significantly longer than men, also report disturbances due to menstruation, pregnancy and climacteric (Krishnan & Collop 2006). Phillips et al (2007) remind us that women and men are differently affected by sleep disorders and also have their sleep disrupted differently by pain, depression and hormonal or psychological changes associated with major life events. These gender-based differences should be considered when assessing patients’ sleeping patterns and views.

Heredity

Sleep quality and length appear to be influenced by genetic factors. De Castro (2002), in a study of self-reported sleep patterns in identical and fraternal twins, demonstrated significant genetic influences on the time individuals went to sleep and woke up, how often they woke up during the night, the duration of their sleep and wakefulness and their feelings of alertness both upon waking up and during the day. Familial clustering of narcolepsy (when sleep frequently intrudes into wakefulness) and idiopathic insomnia has also been observed. It is therefore worth noting in a nursing assessment whether there is a family history of sleep difficulties. It may not, however, always be possible to remedy inherited sleep problems by means of nursing interventions.

Body weight

Weight gain is associated with an increased duration of sleep, while weight loss is often associated with shorter sleep. This has been confirmed by several studies of people with anorexia, including one suggesting that anorexia and bulimia were both linked to sleep disorders (Della Marca et al 2004). As body weight falls, so does total sleep, which also becomes more broken and is interrupted by earlier waking.

Exercise

The effect of exercise on normal sleep is not straightforward and research studies have produced conflicting evidence: some have shown that exercise increases the duration of SWS, whereas some have found no effect and others a negative effect on sleep. Youngstedt et al’s (1997) meta-analysis of 38 studies showed that exercise had different effects on different stages of sleep. The changes were somewhat modest, the greatest being an increase of 10 min on SWS. However, most of this research has focused on good sleepers. A randomised controlled trial of depressed older people showed that exercise had a more profound effect on poor than on good sleepers (Singh et al 1997).

Li et al (2004), also in a randomised controlled trial, studied the effectiveness of tai chi in improving sleep quality in older people who had disturbed sleep. Results demonstrated that older people who took part in the 6 month low to moderate intensity tai chi programme reported significantly improved sleep quality including shorter time to sleep onset and longer sleep duration.

A Cochrane Review of interventions for sleep problems in older age cites one study (Montgomery & Dennis 2005) which found that sleep quality improved after a short (16 week) exercise programme consisting of 30–40 min of walking or low impact aerobics four times a week when compared with no treatment.

Anxiety and depression

Anxiety and depression frequently interfere with sleep. Most people experience these at some time in their lives, associated with, for example, occupational stress, family tension, bereavement, illness or other traumatic events (Lavie 2001). Admission to hospital may be a major cause of anxiety, with all the accompanying worries with regard to illness, investigations or surgery. See Further reading, Carter (2003), Clark et al (2004) and Vena et al (2004).

Physical illness

Cardiac and pulmonary diseases often worsen during the night (Redeker & Hedges 2002, Sutherland et al 2003, Redeker et al 2004). For example, the incidence of asthma attacks increases during the latter half of the night, while angina, cardiac dysrhythmias and nocturnal dyspnoea are all likely to worsen during sleep (see Chs 2 and 3). Metabolic disorders such as Cushing’s disease, Addison’s disease, hyper/hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus may disrupt normal sleep patterns (see Ch. 5). Diseases that mobilise the immune system, whether viral, bacterial or fungal, may be associated with increased sleepiness (see Ch. 16).

Since many areas of the brain are implicated in sleep regulation, any pathology impinging on these sites can cause problems (see Chs 9, 28 and 29). A rise in intracranial pressure, regardless of cause, increases sleepiness, sometimes leading to altered consciousness and death. Interference with the brain stem or hypothalamus may affect the onset and maintenance of sleep.

Pain

People who live with chronic pain commonly experience sleep problems (see Ch. 19). Some types of chronic pain, such as that from peptic ulceration or gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), have a circadian rhythm of increasing intensity at night. General practitioners tend to manage such pain by using medication, sometimes by aiming to relieve the cause, but more often providing symptomatic relief by means of analgesics or antacids. Sometimes the use of antidepressants, as adjuvant therapies, is successful in promoting sleep, since some chronic pain syndromes can be associated with depression.

Nurses are closely involved in giving pain-relieving agents in hospital because of their continuous contact with patients. There has long been an association between pain and sleep loss. Pain has been shown to be a major cause of sleep loss in intensive care units (Jones et al 1979) and the postoperative period (Box 25.3) (Closs 1992, Closs & Briggs 1997). Postoperative patients have strong views about sleep and pain (Closs 1991; Box 25.4).

Box 25.3 Evidence-based practice

A study of patients’ and nurses’ assessments of sleep in hospital

In a study by Southwell & Wistow (1995), 454 hospital patients completed questionnaires about their sleep. This included patients on medical, surgical, care of older people and acute psychiatric wards. Questionnaires were also distributed to 129 nurses working on those wards. Patients and nurses then answered questions concerning the same nights in hospital.