Chapter 10. Promoting mental health

Margaret McAllister and Christine Handley

Learning outcomes

Reading this chapter will help you to:

» understand the reasons for the need to equally emphasise prevention, treatment and promotion in mental health work

» understand how knowledge of developmental stages assists in shaping interventions that serve to promote mental health in young people and their families

» identify the range of mental health strategies clinicians use within the spectrum of interventions for mental disorders

» describe day-to-day practice activities useful in promoting a young person’s mental health and wellbeing, and

» discuss issues important to organisational planning so that services in which you work can build their capacity to provide youth-centred care.

Introduction

In this chapter, we discuss the issue of youth mental health and outline strategies for promoting mental health and wellbeing. As a nurse, you may be working with children and/or adolescents as a specialist CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services) nurse. Alternatively, you may be working with young people in a school setting, in child and family services, in a general practice setting, in a community health centre or as a youth worker with young children who are homeless and living on the streets. You may be a nurse working in a mental health or youth justice residential setting. The young people with whom you work may live in urban, rural or primarily Indigenous communities. The principles of mental health promotion are applicable across all of these different work settings.

We tell a story of a vulnerable adolescent whose experiences flow on to affect the health and wellbeing of her family and, without effective intervention, would be likely to interrupt her relationships and achievements at school, with peers and on into the future. As authors we have attempted to model a person-centred approach to thinking about and working with the young person, as this is a key feature and aim for practice development. We have also included discussion on both knowledge and practice issues, because the development of theoretical understanding and education, as well as practical skills and strategies, are two essential ingredients for change.

Setting the scene: a clinical scenario

The nurse

Imagine you are a postgraduate nursing student who has only recently commenced employment for the first time in a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Centre. You are sitting in on a referral interview for the purposes of assessment. Present is a 13-year-old girl, Chelsea, and her mother, Vicki. Chelsea appears unhappy, angry and uncommunicative. She scowls at you and her mother and gives every indication that she is not happy at all about being here. During the interview, Vicki is critical of her daughter’s behaviour towards her of late and she tells you that her daughter is saying that she wants to die and hates her mother.

Chelsea

Now imagine yourself as a 13-year-old girl who lives with her mum and her younger sister and an older brother. Your mother is always yelling at you and you are convinced that she hates you. Your older brother is a ‘weirdo’ and does horrible things to everyone at home. Your younger sister is a ‘pain’, shares your bedroom and is always touching your stuff. You never have any peace at home. You feel like life is not worth living and write notes to your mother telling her you want to die. You hate school because you are being bullied by an older girl and no one seems to take this seriously. You feel powerless to deal with this on your own. You feel very angry with your family and you hate the world. Nothing good ever happens to you and there is nothing to look forward to.

This scenario, which we return to later in the chapter, represents a typical referral of a young person to a mental health facility. Chelsea and young people like her could be referred by a general practitioner, a paediatrician, a school guidance counsellor or a community nurse. It would be very easy to focus solely on the presenting problems and not see Chelsea as a whole person capable of overcoming the difficulties she is experiencing in her life. Initial energies by the nurse might be directed towards making a clinical diagnosis and treating the identified problem. However, this would be quite unproductive for both Chelsea and her family. Why? How are the concepts of mental health prevention, early intervention and promotion relevant to Chelsea’s situation? Think about the usefulness and limitations of diagnosis within a mental health promotion context. What can you do as a nurse to ensure that prevention and early intervention initiatives are undertaken in your workplace?

Mental health issues in Australia and New Zealand

It is important to be clear about what mental health and mental disorder actually mean, because the way an issue is conceptualised can influences the ways it is prevented and responded to. The term ‘mental illness’ is an ill-fitting descriptor. It is really a metaphor for describing dysfunction. Very few mental health problems can be confidently attributed to physical abnormalities and thus they are not illnesses in the true sense. So too, biological treatments are likely to treat only the symptoms of disorder and do little to promote health and wellbeing in the long term, and do nothing to prevent disorders. Thus, it is important to search for a definition that reaches beyond a biological understanding of mental health and disorder.

Freud, for example, defined mental health simply as the ability to love, work and play. Almost 70 years later, the World Health Organization (2001) describes it similarly. Positive mental health is a:

‘ … state of wellbeing in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’.

In both definitions, the emphasis is on having a rich internal, imaginative and creative life, and the ability to relate with others and engage competently in meaningful activities.

In order to be able to understand the issue of mental health promotion within Australia and New Zealand, it is important to be aware of the extent of the problem that mental disorder creates for individuals and groups. One in five (20%) Australians and New Zealanders will have a mental health problem at some stage in their lifetime, and these primarily develop because of noxious life events such as experiencing violence or stress. Up to 2% will develop serious mental disorders, such as schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder, and these tend to develop during adolescence or early adulthood. According to Mindframe (n.d.), a media resource supported by the Australian mental health strategy, 14% of Australian children and young people aged 4–17 have mental health problems.

This rate of mental health problems is found in all age and gender groups. Boys are slightly more likely to experience mental health problems than girls. Also, there is a higher prevalence of child and adolescent mental health problems among those living in low-income, step/blended and sole-parent families (Sawyer et al. 2000). This means that, each year, about half a million Australian and 115,000 New Zealand youth are affected and will suffer from at least one mental illness episode. Only a quarter of those needing help will receive it.

Certain groups of children and young people are more vulnerable and have particular needs, including but not exclusive to:

» Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Maori children and young people

» children and young people in rural and remote communities

» children and young people separated from their families

» homeless children and young people

» children and young people affected by adverse life events, and

Despite ongoing research, the causes of these illnesses remain poorly understood, and so it is still not possible to accurately predict or prevent their onset. People still lack timely access to services, and many consumers criticise healthcare providers for being patronising or stigmatising (SANE Australia 2004) leading to feelings of isolation or discrimination. Furthermore, most services still tend to be oriented to mature adults who have disability secondary to mental health problems. This makes recovery and adaptation to illness delayed and thus disability and all of its associated costs are increased.

However, alternative approaches are appearing and are highlighted throughout this chapter. One example is Vibe, a New Zealand community action network (see Box 10.1). It is open to young adults in Auckland with experience of mental distress and a passion for positive social change. It was created in 2002 ‘by youth for youth’ and has as its touchstones ‘Youth; Connection; Hope; Growth; Uniqueness; Diversity; Respect and Creativity’. Vibe has an action-oriented focus and implements projects in the youth community that reduce discrimination by and towards youth around experiences of mental distress.

Box 10.1

For information about Vibe, you can go to New Zealand’s mental health promotion and prevention newsletter at www.mindnet.org.nz. This link also allows you to access the Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand, which provides a wealth of mental health information and resources, including demographic information and services for young people in New Zealand. The foundation defines mental health promotion as work to enable individuals, whanau, organisations and communities to improve and sustain their mental health and realise their full potential (www.mentalhealth.org.nz).

The need for better mental health promotion and illness prevention

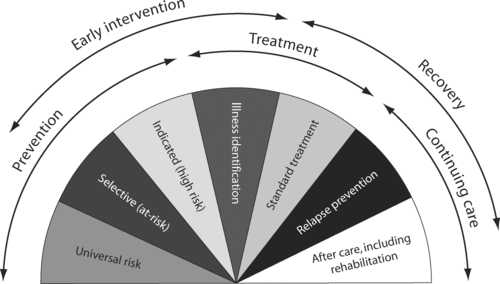

In 1992, following a Royal Commission into the human rights of people with mental illness, the Australian Health Ministers recognised the need to work together and move beyond state boundaries to improve conditions and services for people with mental health problems. A collaborative framework for national reform was established, the National Mental Health Strategy, and a number of important changes have occurred, including prioritising mental health prevention and promotion. New Zealand had a similar experience, with the 1996 Mason Inquiry that led to the establishment of a national Mental Health Commission (1998). Australian and New Zealand clinicians now draw on the US-based Institute of Medicine’s spectrum of interventions model of mental health service delivery (Mrazek & Haggerty 1994). This model (see Fig 10.1) emphasises not just the treatment of disorders, but also prevention, treatment, recovery and health promotion.

|

| Figure 10.1 Source: P Mrazek and R Haggerty R (eds) 1994 Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for intervention research. National Academy Press, Washington DC. |

Nurses working in mental health

In essence, the nurse’s role in mental health is to support the restoration of mental health and wellbeing for individuals and families using skilled, professional care. As mentioned in the introduction to the chapter, nurses with child and youth mental health skills are located in various contexts throughout the community, including the large women’s health units where infant mental health nurses can be found, schools, community health centres, hospitals, and specialised services such as drug and alcohol centres and recovery programs.

Nursing care is provided in a range of ways: by educating the public so that they understand mental health and replace any stereotypes with accurate knowledge; by cultivating a trusting relationship in which mental health problems can be explored and understood; by encouraging people to adhere to treatments such as medications and cognitive behavioural training; by conveying hope so that the person finds meaning in the experience, develops strengths and makes social connections; and by motivating people to make good use of future services and continue therapeutic work (Happell et al. 2002). Even though there are many outstanding, dedicated and professional mental health nurses, in any system there is room for improvement and, in mental health, there are some issues that are in need of practice development.

Some critics have suggested that mental health is hampered by poor interprofessional understanding and this has led to fragmentation of care (Carradice & Round 2004). (See Ch 2 for a discussion of silo culture in health programs.) When hospital services fail to communicate effectively with community services, clients may not be followed up in a timely way and adherence to treatments may diminish (Wright & Cummings 2005). Clinicians may sometimes feel unfulfilled because they lack knowledge and skills that help them be focused and strategic with clients (Bowles et al. 2001).

Solutions to these problems rest in a combination of additional funding for increased staff, improved educational preparation and access to continuing education and training, and introduction of models of care that move beyond a problem-orientation towards a strengths and recovery model (see the practice highlight in Box 10.2). Studies have shown that these changes do produce positive effects, not just for the nurses themselves, but also in better patient outcomes (Aspinwall & Staudinger 2003). For example, Webb (2002) found that clinicians who respond with empathy, a non-judgmental stance and supportive counselling skills have a positive effect on outcomes for young clients. These clients are more likely to stay for treatment, to use the health service again rather than attempt to inadequately self-manage and to have organised follow-up care. At the cultural level, where communities offer sources for self-esteem, a sense of purpose, support from parents, family and community, suicides are reduced and wellbeing is enhanced (Resnick et al. 1997).

Box 10.2

Taking a problem-centred focus is particularly unhelpful when working with young people because, by its nature, a problem orientation tends to search for what’s going wrong with a person, and usually involves an expert applying solutions. This can compound loss of hope and be disempowering. How to be solution-focused with young people remains a challenge. A group of Australian youth health workers (Stacey et al. 2002) collated their strategies. We add to these some practical ideas for application and offer these practical approaches:

• Respect young people as knowledgeable. Ask the person to talk about the ways they cope with present and past challenges.

• Go beyond seeing young people as objects or people at risk. They have strengths and resilience. Use an assessment framework that allows you to understand more than the person’s presenting problem. Make an effort to get to know their talents, gifts, hobbies, dreams and goals.

• Facilitate trust and listen with genuineness. Being trustworthy, reliable, respectful and honourable, even if you do not have the answers or if you make a mistake, are ways for you to show your merit as a caring person.

• Try to see solutions instead of just the problem. Look for presenting problems or issues and then work with the person to set realistic goals to solve each issue. Be solution focused, but not solution forced.

• Focus on exceptions to the problem-laden story so you can use those exceptions to build solutions and build optimism and hope. For example, you could ask, ‘Do you remember a time when you felt closer with your mother and family. What were you all doing at that time? Tell me more about those times.’ Then, you can discuss the kinds of qualities the person conveyed that perhaps might be useful to harness and develop in the present time.

• Involve young people in aspects of the service. For example, young people could be in charge of planning special education events, or for creating resources to promote the service to other young people.

• Attempt to find meaning during all social interactions. Sometimes interactions can be educative and enlightening, rather than always simply fun or a distraction. For example, if you go to the cinema, spend time discussing the strong characters in the movie and help the person identify with the pro-social behaviours.

Developmental stages and mental health promotion: what’s the connection?

A child’s or young person’s developmental level can be conceptualised as a ‘snapshot at one point in time of the accumulation of predictable-age-related changes that occur in an individual’s biological, cognitive, emotional, and social functioning’ (Feldman 2001, in Barrett & Ollendick 2004 p. 28). Table 10.1 sets out an overview of developmental stages/tasks for children and young people.

| Note: This table has its foundations in the seminal work of Kohlberg (1963), Piaget (1952) and Erikson (1963, 1968). Their research work addresses the moral, cognitive and psychosocial development of children and adolescents respectively. Kohlberg’s levels/stages of moral development are not necessarily linked to particular developmental stages, because certain individuals progress to higher levels of moral development than others. | ||||||||

| Preschool | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial development | Cognitive development | Moral development | ||||||

Starts process of separation and becomes more aware of identity Emerging as social being and able to play alongside other children (parallel play) and with other children (reciprocal play) Identifies with parents of same sex and will copy that parent’s behaviour and internalises the attitudes of that parent Has an active imagination and is able to fantasise in play, often using objects in a symbolic manner Will repress unwanted thoughts, experiences and impulses from awareness Can experience a range of emotions, including jealousy, curiosity, joy, grief, affection, anger and fear Developing sense of initiative and dealing with accompanying feelings of guilt Critical period for self-concept develop ment and inner self will be evaluated by what is learned from what others tell them Sees parents as all knowing and all powerful Internalises their family’s way of doing and seeing things and this is used to judge their external environment | Learning to use language and represent objects by images and words Egocentric thinking: finds it difficult to accept the viewpoints of others | Recognises good and bad behaviour Understands that they have done something wrong if punished and that if not punished behaviourmust be okay | ||||||

| Primary school | ||||||||

| Psychosocial development | Cognitive development | Moral development | ||||||

Directs energy towards personal accom plishments, being creative and learning Can tell the difference between fantasy and reality Learning to monitor certain skills with growing confidence Learning to associate performance with rewards and acknowledgment from significant others (e.g. parents/teachers) Needs approval from others to confirm self-worth Mastering social and mental skills in school environment Interested in making things and using toy equipment to act out themes that are dominant in their lives Compare themselves socially to peers and are increasingly influenced by them. Learning what they are good at and not so good at Perceptions of friendship developing Able to acknowledge negative and positive aspects of themselves, but often attribute the cause of negative achievements to external sources. With growing ability to be selfcritical, may internalise their problems by blaming themselves | Thinking is still egocentric Increasing ability to classify objects and think logically about objects and events | |||||||

| Adolescence | ||||||||

| Psychosocial development | Cognitive development | Moral development | ||||||

Experiencing great transitional, personal and physical change towards adulthood Developing a more coherent sense of self and emotional independence Absorbed with their own inner world and emotional connectedness Deep emerging concerns about personal appearance, body image, sexuality and the future Often feels helpless, hopeless, sensitive, misunderstood and ignored in their pursuit for independence Can fluctuate between states of extreme happiness and sadness | Able to think logically about abstract propositions and test hypotheses systematically Becomes increasingly concerned with hypothetical propositions, ideological problems and the future | Understands the morality of social contract and accepts laws that protect the rights and welfare of others Avoids violation of rights Internalises moral principles and will voluntarily act in an ethical manner | ||||||

A developmentally oriented treatment and/or management plan needs to take into account the critical developmental tasks and milestones pertinent to a particular child’s or adolescent’s health problem—for example, self-control and emotion regulation in early childhood or the development of behavioural autonomy and strong peer ties in adolescence (Barrett & Ollendick 2004). Table 10.1 is a conceptual guide only, as in reality the course of developmental changes varies across individuals. Further, some behaviours that are developmentally normative at younger ages (e.g. temper tantrums) are developmentally atypical at later ages. We also know that two young people with similar mental health problems/issues may have developed such problems along very different pathways. The practical application of developmental conceptual models for children and young people is addressed below.

In relation to working therapeutically with children, young people and their families or carers, we know that:

» Positive resolution of developmental tasks moves the adolescent towards adulthood. Assisting the child and adolescent to achieve ego competency skills (Strayhorn 1989, in Stuart & Laraia 1998) and developmental tasks at different stages is the role of significant adults in their lives (e.g. parents, relatives (including grandparents), teachers or foster carers). Parents and primary caregivers can often struggle with understanding the reasonable expectations for a child and adolescent of a particular age. Sometimes, a counsellor or therapist helps the adult carer to fulfil their roles through developing a better understanding of developmental milestones, tasks and expectations. This was certainly the case when working with 13-year-old Chelsea and her mother Vicki. Vicki needed help to understand normative developmental behaviour, not only as it related to Chelsea but also to Chelsea’s siblings. Vicki became a more effective parent through being able to distinguish more clearly the different developmental needs of her children (e.g. allowing older children to have a later bedtime or to have a greater say in decision making) and this impacted positively on Chelsea’s welfare and emotional wellbeing. See Box 10.3 for a summary of the nine ego competency skills.

Box 10.3

Strayhorn (1989) identified the following nine skills that all children need to become competentadults:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access