Chapter 3. Promoting health in an era of globalisation

Introduction

Health promotion is one of the most important strategies a health professional can use to develop community capacity.

Although the determinants of health may change according to the characteristics of any given community, the centrality of equity as a human rights issue remains constant. Equity is a product of the political environment. It is forged in the relations between governments, between different sectors of society, between cultures, neighbourhoods and families. Policy decisions determine the extent to which social justice can be achieved; whether people experience peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem and sustainable resources. These decisions reverberate down from the highest levels of government to the community level, dictating the creation and distribution of wealth, and the conditions and resources that will determine the extent to which individuals, families and communities will be able to achieve health. When the policy decisions engage civic participation at the grassroots level there is a greater chance of relevant, useful and effective health outcomes.

As health professionals in today’s world we have an obligation to develop a sound knowledge base as well as an attitude of responsiveness to the features and occurrences of community life. Both are shaped by global knowledge and events as well as community characteristics. Health promotion pivots on the exchange of knowledge. By sharing knowledge in the context of interactions with the community our health promotion plans and objectives are strengthened and made relevant to their circumstances. In turn, the community gains health literacy and empowerment. This is health promotion in the 21st century. It is based on rational planning, responsiveness, inclusiveness, advocacy and community participation. It is creative, stimulating and professionally rewarding. Most importantly, it requires social and political activism based on global events, so this is where we will begin laying the foundation for promoting health in the community.

Globalisation

Globalisation refers to the integration of the world economy over the past quarter century through the movement of goods and services, capital, technology and labour (Labonte & Schrecker 2007a). This integration has led to a situation where economic decisions affecting people in all corners of the world are influenced by global conditions. When we first encountered the notion of a globalised world in the 1980s it seemed a palatable idea. A globalised world held the promise of increased markets for goods, porous borders through which

Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

1 explain globalisation and its role in contemporary health promotion

2 undertake a community assessment

3 plan a health promotion intervention

4 explain how knowledge of health and place can be used in promoting health

5 analyse the relevance of the Ottawa Charter and subsequent charters as a basis for health promotion

6 explain the difference between the risk factor approach to health promotion and the social determinants approach

7 develop a comprehensive strategy for promoting health in a particular community.

Globalisation is the integration of the world economy through the movement of goods and services, capital, technology and labour.

The political environment that paved the way for globalisation was one that valued not only free trade between nations, but deregulation of financial markets and a host of other financial decisions that ultimately created the 2009 global financial crisis. This is neoliberal politics, which began in the mid-1970s with an intellectual blueprint that supported the virtues of free markets and private ownership (Labonte and Schrecker, 2007a and Navarro, 2009). The World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) have played a major role in globalisation by encouraging the commodification of such things as labour markets, health care, pharmaceuticals and public pension systems. Together, these three organisations have extraordinary power over global financial decisions and share markets worldwide. They are dominated by the wealthiest nations in the world, which control 48% of the global economy and 49% of global trade (Labonte & Schrecker 2007a).

Global markets have been good for industrialised economies, but they have impoverished many countries, especially those who were already poor. In the 1980s, as globalisation gained momentum and the domestic markets of many developing countries declined, the IMF and the World Bank provided loans to those nations that agreed to adopt ‘structural adjustment policies’ in order to reorganise their economies. As nations this placed them in a precarious, disempowered position. Because the loans were also provided indiscriminately to political leaders who had no moral obligation to defend the legitimacy of their rule, many local communities were deprived of democratic participation in decision-making. This situation has continued to the present time as a number of despotic rulers maintain their leadership through repression (Labonte & Schrecker 2007b). Some African and Asian countries have experienced this for many years. People in Zimbabwe starve to death regularly. In Bangladesh, which is the poorest country in the world, only a fraction of the food aid reaches the poor, the majority of it being given to the government, which sells it at subsidised prices to the military, the police and middle-class families (Navarro 2009). This has led Navarro (2009:440) to declare that ‘it is not inequalities that kill, but those who benefit from the inequalities that kill’.

Many governments attempting to respond to the globalised economy by becoming more ‘business-friendly’, have gradually relaxed their labour standards, health and safety regulations, and other social policy measures that may have provided greater income security (Labonte & Schrecker 2007b).

Globalisation has arisen as a result of developed countries implementing free trade policies. This is called a neo-liberal approach to politics

Workers engaging in the new production processes became exposed to new workplace hazards and industrial pollution, which have been tolerated to increase labour market position. For many, increased casualisation of labour and excessive hours of work have become the norm. As casual, rather than permanent staff, they are readily open to exploitation by their employers. As a result, many workers in the developing countries have become deskilled, magnifying inequalities between rich and poor countries (Labonte & Schrecker 2007b).

Globalisation has had a profound impact upon developing countries, resulting in an increase in health inequalities for many people already living in disadvantaged circumstances.

A further layer of disadvantage has arisen by privatisation. Many countries have privatised what had previously been public services, and this has led to user fees for health care and education, which then became unaffordable. Some women have been forced into relying on ‘survival sex’ with its high risk of abuse and HIV/AIDS. Across entire populations, high external debts have increased personal income taxes. At the government level many currencies became devalued as interest rates to external banks increased. This occurred just as world prices were rising, when the economic elites became worried about tax increases and the threat of future devaluations. The result was an outflow of foreign loan repayments to safer, tax-free havens, which stripped the country producing goods of tax funding that may have been used to improve citizens’ quality of life. With a financial crisis looming, internationally mobile investors tried to move their funds to safer ground. In some cases (in African countries) roughly 80% of all foreign loans flowed straight back out the same year (Labonte & Schrecker 2007b). Over the past decade, rich countries have offered some debt relief to various recipient countries, but the terms and conditions of this relief are so strict that many have not been seen as desperate enough to qualify, and three countries have actually seen debt increase over that time (Labonte & Schrecker 2007c).

The pros and cons of globalisation

Clearly our globalised world has brought significant changes to community life, some more dramatic and far-reaching than others. In many circles, the very mention of ‘globalisation’ polarises opinion, attracting praise from some quarters and criticism from others. Globalisation optimists argue that economic arrangements since globalisation have added wealth to various nations, reducing absolute poverty (the total number of people living in poverty). Global technology has also enhanced knowledge for many people, providing instant electronic access to a wealth of information, including health information. Information disseminated throughout the world in this way has also connected ideas and research data, in some cases leading to greater collaboration in research and, ultimately, treatment strategies. It has also led to greater educational opportunities for some who would not have had the opportunity to study outside their countries.

Globalisation has both pros and cons. Pros include improved access to information and greater educational opportunities. Cons include the feminisation of poverty and decreased accessibility to many health services.

Globalisation pessimists argue that the benefits are outweighed by the negative effects of a globalised world. Researchers cite the health effects of excluding some nations from the global market, particularly the developing countries, many of which are already suffering from communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS, hepatitis and malaria (Huynen et al 2005). Falk-Rafael (2006) cites the colonising character of globalisation as contributing to the feminisation of poverty in such countries, which has seen poverty rates among women continuing to grow. Poverty, gender inequality, development policy and health sector reforms that have established user fees and reduced access to care have been linked to six million deaths per year from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria (Labonte & Schrecker 2007a). The impact on accessibility of health services is profound. Many health services have become privatised, with increasing user fees. Multinational pharmaceutical companies dominate the trade in medicines, creating higher costs with no accountability to current and future generations in relation to local development or any social or environmental damage they may cause (Baum, 2009, Labonte, 2008 and Labonte and Schrecker, 2007a). Developing countries have also experienced an alarming brain-drain, with mass migration of health professionals stripping many countries of their workforce (Labonte & Schrecker 2007a). Africa, with 25% of the world’s burden of disease and 3% of its workforce, loses 20000 health professionals a year to migration (Robinson 2009). The net loss of these health workers has caused the near collapse of already fragile health systems.

These outcomes of the global marketplace have had a profound effect on nutrition, with certain countries being unable to produce their own food. The result has been a vicious circle of poor nutrition, forgone education and ongoing illness among the most disadvantaged in society (Navarro 2009).

Globalisation has also engendered concerns about losing cultural identities, languages and the right to choice in securing the best level of health for the most number of people. The reality is that as globalisation has progressed, there have been greater disparities between rich and poor countries, and between the rich and poor within most countries. The disparities are evident even in the United States (US), where multinational alliances between the automobile industry and the gasoline and oil industries are responsible for a failure to develop and maintain public transportation. A large proportion of the US population has no health insurance or are underinsured, often leading to family bankruptcy (Navarro 2009). For many, these disparities have led to declining health standards. Despite the promise of generating new wealth globalisation has failed to deliver equity in its distribution across populations.

What’s your opinion?

Globalisation has had a significant impact on individuals, families, communities and nations. What negative and what positive impact has globalisation had on you as an individual. your family and your community?

After three decades there is greater understanding today of the perils of globalisation, yet it is escalating beyond all expectations. As all nations now trade more of their national income internationally, world trade has increased. This includes an increase in the illegal drug trade, which takes advantage of global finance systems, new information technologies and transportation. Migration has also increased, accompanied by a globalisation-induced increase in cultural tension and intolerance of others. As a result, the world is experiencing major social changes, manifest in increased individualism and social exclusion. Exclusion has created ‘disintegration from common cultural processes, lack of participation in social activities, alienation from decision-making and civic participation, and barriers to employment and material sources’, eroding social capital and creating fertile soil for conflict, violence, and increasing illegal trade in alcohol, firearms and drugs (Huynen et al 2005:7).

Globalisation as a health promotion variable

As it has reverberated around the world, we have begun to understand globalisation as a comprehensive phenomenon, far beyond economic processes. In health promotion terms it has been called the quintessential upstream variable because it has created changes to the social determinants of health (SDOH) at the most fundamental level of daily life (Labonte & Schrecker 2007a:1).

Proximal factors that influence health are those that directly cause disease or health gain (e.g. choosing a healthy diet). Distal factors that influence health are those that are a step removed from a person’s life (e.g. a policy that ensures healthy food is available at an affordable price).

Its profound effects extend to both proximal and distal factors that influence health (Huynen et al 2005). Proximal factors are those that directly cause disease or health gain (health behaviour, a clean environment), whereas distal factors are a step removed from the person’s life and are mediated by a number of other factors. For example, choosing a healthy diet is a proximal factor (closest to the person) influencing health. Distal factors that add other layers to that person’s health choices can include the health policy that ensures access to healthy food at an affordable price, the economic environment that allows trade and marketing of certain foods, the socio-cultural environment that fosters knowledge and health literacy to assist food-related decisions, and the technology to store, supply and regulate the security of food.

Lifestyle choices for members of any given community are therefore dominated by global trade. Although technology and global policies can be used to discourage unhealthy behaviours by taxing unhealthy products (e.g. tobacco) the reverse is often the case. Many companies, especially in the fast-food industry, take advantage of opportunities for global marketing to promote diets high in fat, sugar and salt (Baum 2009). Some countries whose resource base leaves them unable to produce sufficient foods become ‘food insecure’ from being at the mercy of global markets. Multinational companies such as Monsanto and McDonald’s, for example, have been responsible for extinguishing certain gene pools within developing countries’ ecosystems (Falk-Rafael 2006).

Lifestyle choices by any member of a community are dominated by globalisation.

The companies’ quest for productivity (with bioengineering and products heavily dependent on pesticides) and uniformity (McDonald’s demand for only one variety of potato) effectively eliminate their capacity as growers (Falk-Rafael 2006).

Where this type of food insecurity is extreme, food aid can be advertised, but in many cases, food-insecure countries become vulnerable to shocks that reduce the global market, further impinging on their ability to purchase what they need. Even water is now traded on the global market as a commodity, and this has major health impacts both globally and locally. In Australia, for example, it has become commonplace to trade water rights, disrupting the ecosystem as well as the local rural economy.

One of the most profound impacts of globalisation has been a growth in urbanisation and the subsequent detrimental effect on the environment.

Although the effects of globalisation on the SDOH are asymmetrical, there have been some common trends. With rapid population growth there has been increasing urbanisation of populations throughout the world. This often creates further disadvantage as urban economies become less industrialised and more geared towards commerce and tourism, with the poor shifted to suburban or remote locations. This leaves many people having to rely on fewer support systems and inferior services, often with a lack of public transportation and protective services (Labonte & Schrecker 2007b). Urbanisation also disrupts the ecological footprint, with overconsumption, declining air and water quality, loss of biodiversity, chemical pollution and decline in living environments, especially for the poor (Baum 2009). This compromises environmental sustainability. Those who live in industrialised cities experience deterioration of the environment disproportionately as they tend to live energy-intensive lifestyles, consuming 75% of the world’s energy, through excessive use of automobiles and other polluting devices. Cars not only make cities congested with high pollution levels, but they cut people off from social interactions (Baum 2009).

Urban dwellers often have exposure to a wider range of harmful environments than rural people. A case in point is the ground contamination caused by the production of orchard chemicals in one of the most picturesque regions of New Zealand. Attempts have been made over the past several years to clean up the contamination, and the local District Council has pronounced the area safe for redevelopment of commercial and residential interests. However, the ground will never again be entirely contaminant free and ongoing monitoring of soil and groundwater will continue indefinitely (Pattle Delamore Partners Ltd, 2009, Whitehead, 2009 and Wise, 2008). This example demonstrates that although some environmental effects may be ‘cleaned up’ the long-term impact industrial pollutants may have on the environment, on people and on places is immeasurable.

Global warming and the resultant natural disasters of rapidly changing climates, also exacerbate the health effects of urbanisation. The effects of a deteriorating physical, social and political environment because of climate changes can lead to exploitation and control over technology, finances, employment and a host of social and structural determinants that disadvantage women, the poor, Indigenous and other vulnerable people (Baum, 2009 and Robinson, 2009). The impact of climate change is so important to health that an international alliance has been formed on climate justice, under the Global Humanitarian Forum chaired by Kofi Annan, the former Director-General of the United Nations (UN) (Robinson 2009). The major challenge lies not only in reducing emissions causing global warming, but ensuring that those disadvantaged by environmental degradation are able to achieve an adequate standard of living and the dignity to lead the lives they choose (Robinson 2009).

Health promotion strategies for global health

Global health promotion is a central tenet of global development, and therefore a core responsibility of governments. It is also a key focus for communities and civil society, including the corporate and business world. Labonte (2008) suggests that promoting health at the global level requires two major changes in how we deal with globalisation. These include social risk management, which means aligning social protection with global realities. This would see households earn their keep, by smoothing their consumption patterns in response to external events, ranging from natural disasters to financial crises. Such an approach does not take into account how crises are created by global forces or the disproportionate effect on the most vulnerable. The second seeks to blunt the negative impact of the global marketplace through the actions outlined in Box 3.1.

BOX 3.1

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

knowledge can be linked with wider societal and global knowledge and aspirations. This requires research, resourcefulness, information exchange, receptivity to new ideas and strategies, an attitude of inclusiveness, and a focus on the dual goals of equity and community empowerment. The process begins by building the knowledge base, then using strategies that have been shown to be effective in facilitating better health for communities in the context of their local conditions while keeping an attitude of openness to new ideas and approaches.

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

• Recognition of access to resources as a human right.

• Reframing globalisation in terms of social obligations and new institutions for global governance (Labonte 2008).

• Regulating global market forces in a way that is people-centred rather than capital-driven.

• Public policy development based on a vision of the world that people matter and social justice is paramount.

• Developing a global contract where industrialised countries support contemporary welfare states (Labonte & Schrecker 2007c).

The approach mentioned in Box 3.1 is closely aligned with PHC principles and responds to the SDOH. Labonte (2008) urges critical appraisal of the health problems that have become inherently global in cause and consequence. He outlines five different ways of conceptualising health in relation to globalisation: health as security, as development, as global public good, as commodity and as a human right. Health as commodity is a convoluted way to view health. It represents the worst of globalisation, in reducing health to goods (drugs, new technologies) and services (private health insurance, facilities or providers) with trade having the outcome of maximising profit rather than health. The other four concepts embody a type of ‘transnational health activism’ suggested by the Bangkok Charter’s recommendation that health be central to the global development agenda (Labonte 2008:467).

Fear of epidemics that may influence global trade, finance or travel has been used as a means of privileging high-income nations and in particular the industries that create drugs aimed at preventing or treating such epidemics.

Health as security

When health is seen as security it conjures up fear of bio-terrorism, terrorists, and the general inclination towards border protection, ‘whether the invaders are pathogens or people’ (Labonte 2008:468). This idea has given more political clout to public health measures, particularly with global epidemics, but it is also associated with ‘repressive political measures’, such as the rhetoric and actions of the war on terror (Labonte 2008:468). Instead of encouraging high-income nations to help those less fortunate it has privileged those diseases most likely to inconvenience global trade and finance or travel to wealthy countries. Fear of epidemics such as avian flu or H1N1 (swine flu), has also proven a major windfall for the pharmaceutical industry, particularly Roche, the company that makes Tamiflu. Labonte (2008) suggests a shift from the national security approach to one of working towards human security. The latter is based on a core moral value of individual security, including income, health care, housing, education, environmental security and other essentials for life (Labonte 2008). This indicates the political nature of health promotion, and the need for vigilance, activism and community participation to shift ideas, attitudes, resources and power to focus on strengthening the health and wellbeing of the population (Sparks 2009).

Health as development

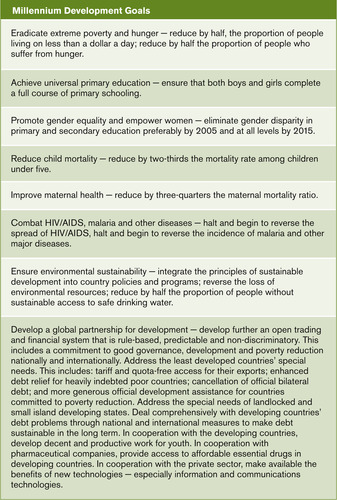

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have been described as ‘the most concentrated and collected global statement of development intent in human history’ (Labonte 2008:470) (see Figure 3.1). MDGs clearly situate health as a development outcome. The MDGs, to be achieved by the year 2015, were defined at a UN summit of 191 nations to address the effects of poverty on health in the developing nations. They are aimed at addressing extreme poverty, hunger, disease, lack of adequate shelter and exclusion while promoting education, gender equality and environmental sustainability (Sachs 2005). The Millennium project, under the auspices of the Director-General of the UN, is based on the assumption that sound, proven, cost-effective interventions can ameliorate and often eliminate extreme poverty, especially where it is most needed, such as in the countries of sub-Saharan Africa. To achieve the goals requires investment of wealthy countries in the poorer nations to help develop capacity in education, the environment, health care, nutrition and social programs, especially those that foster equity.

|

| Figure 3.1 |

The intention of the MDG project has been no less than to change the world. If the goals are met, 500 million people will be lifted out of extreme poverty. More than 300 million will no longer suffer from hunger.

The Millennium Development Goals are a set of goals designed to address the effects of poverty on health in developing nations.

The lives of 30 million children and 2 million mothers will be saved. Hundreds of millions of people will have safe drinking water and basic sanitation. Hundreds of millions of women and girls will go to school, be able to access economic and political opportunities and be safer and more secure (Sachs 2005). Yet to date, there have been only modest gains in achieving the goals, although there has been a renewed Global Campaign for achieving the MDGs, which is centred around improving maternal health through innovative financing and better health services (http://www.un.org/News/briefings/docs/2008/080925_MDG_Health.doc.htm [accessed 15/07/09]). However, long-term trends show that progress has been slow. The ratio between the richest and poorest countries continues to increase significantly, and the number of people living in absolute poverty (less than $US2 per day) has also increased (Baum 2009). One billion people worldwide try to survive on less than $US1 per day while 35000 of the world’s children die (Mooney & Ataguba 2009).

Criticisms of the MDGs focus on the lack of equity and inclusiveness of the goals in terms of human development. The objective of human development is to try to ensure that everyone develops to their maximum potential as a human being (Hancock 2009). The UN Development Programme is based on the holistic nature of human development in terms of securing essential areas of choice, including political, economic and social opportunities for being creative and productive, and enjoying self-respect, empowerment and the sense of belonging to a community (Hancock 2009).

Despite the potential for significant improvement in health outcomes for the world’s poorest, progress in achieving the Millennium Development Goals has been slow. Critics argue that this is due in some part to the lack of equity and inclusiveness of the goals in terms of human development.

Because of the way the goals are cast, and their emphasis on economic goals it would be possible to meet their criteria by improving the health of the wealthy while worsening the health of the poor (Labonte 2008). The goals are also difficult to measure and do not identify the causes of the problems that need to be addressed (Labonte 2008). They are unambitious, setting only minimal standards (Baum, 2009 and Labonte, 2008) and the target of Goal 8 to further an open trading and financial system may be at odds with the others, given the disadvantage created thus far by open markets (Labonte 2008).The MDGs have been lauded for their call to wealthy countries to support those at an economic disadvantage. However, even in this respect, there have been significant problems in relation to foreign aid. In general, with the exception of the Nordic countries, aid levels remain ungenerous (Labonte 2008). Aid given to Africa has not created economic development, but instead most has been lost to ‘capital flight’ (the removal of funds to wealthy countries). Some aid arrangements have been used to pressure poor recipient countries into trade treaties that favour wealthy, donor nations. Over 60% of the increase in donor aid between 2001 and 2004 has gone to Afghanistan, Iran and the conflict-ridden, mineral-rich Democratic Republic of the Congo, which together constitute less than 3% of the world’s poor. This calls into question whether aid is protecting the interests of the givers or the recipients (Mooney & Ataguba 2009).

With the exception of Nordic countries, humanitarian aid contributions by developed countries remain ungenerous.

Australia provides $A42 billion in aid, yet the funds are now tied to long-term anti-terrorism projects in the Asia–Pacific region, officially reoriented towards combating terrorism and promoting regional security (Mooney & Ataguba 2009). In New Zealand, election of a National government in 2008 has seen a re-orientation of New Zealand aid policy from a focus on social equity to one on sustainable economic growth (McCully 2009), resulting in a total redistribution of New Zealand’s aid. This demonstrates how even within countries, differing government agendas can have a wide-ranging impact on global health (http://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/aid+increases+nzaid+changes+focus).

These outcomes suggest that the development agenda and the notion of ‘aid’ needs to be recast in terms of human potential through ‘redistributive obligations’ rather than market performance (Labonte 2008:473). This would help temper investments in health to distinguish the objective (human development) from the tool (economic growth). An alternative way of approaching global health is to see health as a public good.

Health as a global public good

One approach to promoting global health that has gained momentum since the 1990s is the notion that when wealthy nations provide health assistance to the less fortunate it is not only humanitarian aid, but a selfish investment in protecting health in their own population (Smith & MacKellar 2007). This conception of health is one that evokes community, where the emphasis is on the collective, and stable, sustainable systems that support health and nation building. Globally, this idea of sharing would see a broader perspective where all countries became concerned about risks (risk pooling) and worked towards developing common financial regulations to benefit everyone, not just those in positions of wealth and power (Baum, 2009 and Labonte, 2008).

The Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) has done some analysis of financial possibilities in relation to this type of aid, especially in the context of the 2009 global financial crisis. They agreed that it was important for the world’s economies to prop up the financial systems of industrialised nations to prevent normal families from falling victim to the lack of credit, but the amount spent on the initial stimulus packages at the beginning of the crisis was beyond what was required. The commission estimated that for $100 billion, far less than what was spent in the stimulus packages in either the US or the United Kingdom (UK), the world’s slums could have been upgraded (Marmot 2009). For one-ninth of what the banks received, every urban citizen of the world could have clean, running water, and every child could have free education (Marmot 2009). This leaves us to ponder the argument that even global institutions such as financial organisations must be based on global social justice and world citizenry, without a return to the open, competitive market system of the past (Mooney & Ataguba 2009).

Health as a human right

This view of health is that conveyed in the People’s Health Movement, which has support from 40 countries. Its focus is on a bottom-up mobilisation of action through training, capacity building, documenting health rights violations, and lobbying governments for policy change. It has created the momentum for a global health ethic which would entrench rights, regulations, redistributive justice and a concern with the inequality of persistent poverty.

Viewing health as a human right redirects the focus of addressing health issues from a top-down, government-directed approach, to a bottom-up, people-led approach, where addressing inequality between people and nations is seen as a priority.

Health promotion in this context is through global health diplomacy, based on the need for ethical, rights-based, public good, development, and security in the foreign policy of all governments (Labonte 2008). Baum (2009) uses the metaphor of a nutcracker, explaining that grassroots or bottom-up pressure is most effective when combined with top-down policy action to open up the issue for discussion.

Employment is absolutely critical to human rights. Mary Robinson, the former UN Commissioner for Human Rights argues that job creation must be the central objective for private companies as well as governments. This includes respecting core labour standards such as non-discrimination and workplace health and safety, promoting social protection by income security and supporting those who are ill, providing insurance for older persons, and promoting social dialogue between governments, employers and workers (Robinson 2009). Questions to ponder in relation to health promotion in an era of globalisation are listed in Box 3.2.

BOX 3.2

• How can knowledge of the global environment be used to promote health at the local level?

• What social, cultural and environmental conditions can be modified to create the conditions for health in a community?

• How can community members become engaged in civic participation to change the social and structural conditions that impinge on their health?

• What actions can health professionals take to participate in political processes that have an effect on health and wellbeing?

• How can health professionals help people develop health literacy, empowerment and health capacity?

• How can scientific knowledge be used to underpin health promotion strategies?

• What health promotion and health education strategies will achieve optimal results for which types of societies, communities and populations?

Building the evidence base: the population approach

Promoting health involves getting to know a community, its people, their resources and their goals, and developing an understanding of how this local

Promoting health requires research, resourcefulness, information exchange, receptivity to new ideas and strategies, an attitude of inclusiveness, and a focus on the dual goals of equity and community empowerment.

Epidemiology is the traditional starting point for developing a base of evidence on health and its determinants in specified populations. Epidemiological studies are designed to gather sufficient data to monitor trends and inform planners and policy-makers on ways of improving health (Bezruchka, 2006 and Kawachi, 2002). Until recently, epidemiology has been overly focused on uncovering the causal connections between exposure to risk factors and the development of disease, rather than health and wellbeing.

Epidemiology is the study of factors that affect the health of populations.

Epidemiology as a discrete area of study, began with John Snow, an English physician who was concerned with the number of people dying of cholera. He plotted the incidence of deaths in a London neighbourhood, and found an association with the pump supplying the local drinking water by talking with local residents about their daily habits. Although he did not know the causative agent (a bacteria) he understood that the source of the problem was the water supply. He removed the pump handle and the death rate declined. His actions therefore controlled the epidemic.

John Snow had a major influence on epidemiology (www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow.html) yet his action-oriented approach, to follow up on epidemiological data is rarely included in accounts of epidemiological studies (Bezruchka 2006). Snow and others investigating the sources of diseases in the 19th century began to draw a connection between poverty and material disadvantage and ill health, which called into question whether dissecting single factors provided a viable base of evidence for intervention (Bezruchka 2006). Single risk factors are easy to measure and there are clear-cut statistical conventions for linking them to specific outcomes. However, the effects of culture, community trust and fairness, and the elements of social capital are more challenging. Yet the evidence base is incomplete without this knowledge, which is a missing link in the global research agenda.

The global burden of disease project

To inform national and international health policies for prevention and control of disease and injury, in 1990, researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health, the World Bank, and the WHO began an epidemiological investigation into the worldwide burden of illness. This is called the global burden of disease (GBD) study (WHO 2005). The goal of the study was to draw on many sources of data to develop internally consistent estimates of incidence, health state prevalence, severity and duration, and mortality for over 130 major causes of disease. The original studies identified the major causes of death, disability and disease for various demographic groups in eight regions of the world (Murray & Lopez 1997a). The findings calculated the burden of disease (Murray & Lopez 1997b). Some 20 years later, the original findings have limited usefulness for health planning at the local level, partly because of the way data were aggregated to show an international picture, and also because of the time delay between collection and dissemination of the information. However, the GBD study has provided a template for calculating where each country fits on an international scale of health, how widespread some diseases are, particularly the lifestyle diseases such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and what trends are most likely to occur in the future. What is as yet unknown is how health service planners will use the data to persuade governments to develop population-wide strategies for better health, or to fund protective supports that will help people live healthier lives.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access