Professional Relatedness Built on Respect

Of course the questions had to do only with illness. By the time he was through, this young man would know all about her years in the sanatorium, about her hysterectomy, and about her damaged lungs—and that is all he would know. Laura was amazed to discover that she was struggling to make a connection on another level. In a hospital one is reduced to being a body, one’s history is the body’s history, and perhaps that is why something deep inside a person reaches out, a little like a spider trying desperately to find a corner on which to begin to hang a web, the web of personal relation.

—M. Sarton1

Chapter Objectives

In this chapter you have an opportunity to take the insights you have gained from the book so far and put them together in the context of your relationship with patients. The authors have encouraged you to think about how you would respond to some relational challenges, but now you have the background to focus directly on the relationship. Your situation is like a bridge that needs strong supports because you and the patient always remain individuals, but your mutual goal is to be able to “bridge the gap” between you in ways that meet those goals (Figure 10-1).

Some characteristics described in this chapter are essential for any relationship to thrive. For example, trust and reassurance are fundamental. A psychological phenomenon called transference can always be a factor in how you view and respond to another person, and they to you. At the end of the chapter we come back to the idea of professional caring, emphasizing everyday behaviors that express it.

Build Trust by Being Trustworthy

Trust connects the patient’s ability to feel that he or she is being respected by you with your intent to provide your professional services. In the traditional physician-patient relationship, trust was thought to mean having blind faith in the physician. This type of trustworthiness was just about all that health care providers had to offer because until the beginning of the 20th century, a patient had less than a 50% chance of benefiting medically from an encounter with a physician. This total reliance on trust as the support beam allowing the two individuals to “meet” meant that the doctor should be benevolent and protective toward patients.

Modern insights regarding the role of trust in human relationships are molding the understanding of the health professional and patient interaction today. In the view of developmental psychologists, trust plays a central role in a person’s developmental task of figuring out when to depend on others and when to be cautious. Therefore, a professional is worthy of trust when patients feel secure to exercise their decisional capacity appropriately. But what, exactly, does such trustworthiness look like in the day-to-day health professional and patient relationship? In an article entitled “Engendering Trust in a Pluralistic Society,” Secundy and Jackson make the following observation:

When a patient speaks of trust in a health care setting, he or she is essentially speaking about a comfort level, a feeling of safety, a belief that he or she can rely on people with power not to hurt or exploit him or her . . . Such positive feelings can ensure appropriate cooperation and compliance during the course of an illness. When such feelings are absent or ambivalent, the patient’s behavior can influence outcomes negatively. There are several areas in which trust is relevant: The patient can trust or distrust the system of health care itself, the specific institution or setting in which health care services are being delivered, and the person or persons providing service or care.2

For each area of trust experienced by the patient, the health professional has done his or her part by being trustworthy.

Competence and Trust

![]() knowing what you know and are skilled to do,

knowing what you know and are skilled to do,

![]() being aware of your professional and personal shortcomings, and

being aware of your professional and personal shortcomings, and

![]() applying the communication skills discussed in the previous section of this book.

applying the communication skills discussed in the previous section of this book.

You have learned that a patient’s request for your services is usually generated by the presence of a sign or symptom that manifests itself in the form of pain, lack of ability to function, or some other discomfort. The patient counts on you and your colleagues, all strangers to the patient, to learn his or her diagnosis, what it means for his or her everyday life, and what he or she needs to do to initiate and follow a treatment process. People also seek your counsel about how to stay healthy and prevent health-related difficulties.

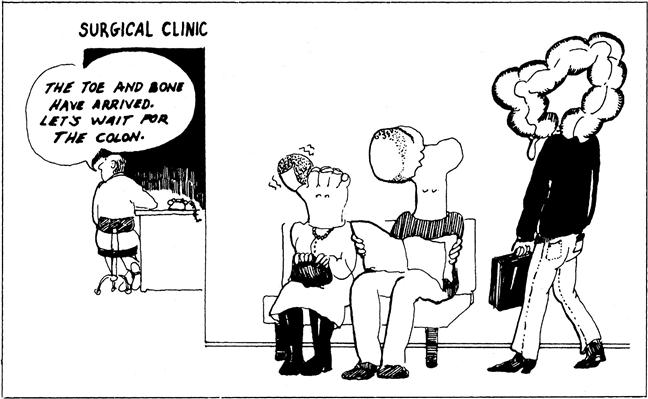

In each instance patients come to you having to decide whether or not to trust that your professional training prepares you to competently address pertinent health-related needs and questions. Your role in the relationship is to be trustworthy through actions that demonstrate you are there to meet their reasonable expectations in ways you are professionally prepared to do. Their trust grows as you interact with them. At the same time, for genuine trust to take root in the relationship the patient also must be convinced that he or she is viewed as something more than a symptom or an interesting medical case or a body part (Figure 10-2). Unfortunately, health professionals and institutions are sometimes insensitive to the messages they are conveying in this regard. For example, the “bone clinic,” the “allergy clinic,” the “heart specialist,” and the “obstetrics nurse” all convey images of body parts or symptoms rather than living, breathing human beings. Some have called this phenomenon “thinging.” In it the patient is made to feel more valued for the “interesting thing” that he or she is bringing to the health professions setting than because of being a person with a human need.

Common sense suggests that patients should not trust you if you seem more interested in their diagnosis or symptom than in what these mean to their well-being as persons. To the extent that you recognize the mistake of “thinging,” you will have taken a giant step in engendering a genuine bond of trust as the bond between you and the patient.

Sometimes being judged as trustworthy by patients is not completely in your control no matter how well intentioned you are. You are a part of a system. For example, government or institutional policies determining your course of intervention may shortchange a patient or discriminate against a group, resulting in their understandable lack of trust in the system or in you personally. This does not relieve you of responsibility. Being trustworthy requires that, as you learned in Chapter 2, you participate in the change of deleterious or unjust policies whenever possible.3 Rogers and Ballantyne found in their study of women patients that when they felt themselves to be among the safe, privileged variety (e.g., white, economically well off, younger) they may develop a distorted trust in the health professional to make policies work on their behalf when that is not the case. The result can be care that is no more suited to this patient than to the one in a socially disadvantaged position.4

In most cases you are also one member of an interprofessional health care team, and this, too can have an impact on whether the patient will believe you are trustworthy to deliver competent care. Being trustworthy requires some things you can do, such as:

![]() be an alert and active participant in team decisions appropriate to your expertise,

be an alert and active participant in team decisions appropriate to your expertise,

![]() let the patient know when you are going to tap the expertise of others more expert than you.

let the patient know when you are going to tap the expertise of others more expert than you.

Occasionally, health professionals find themselves in awkward situations knowing that the patient’s trust might be based on unreasonable expectations. For example, consider the case of Mrs. Gleason, her family, and the team:

This situation was uncomfortable for the health professionals who felt they had Mrs. Gleason’s interests at heart but could not meet her and the family’s expectations. In the end all you can do in such situations is to continue to search for ways to give the patient and family a basis for exploring new options open to them.

Honesty, Reassurance, and Trust

To be “assured” is to have a feeling of confidence and certainty. Reassurance helps restore that feeling when it is lost. No matter what their differences in other regards, all patients trust you to offer honest reassurance about what they can reasonably expect from their encounter. Reality testing is a term often used in the health professions to denote that the care provider keeps the patient on track from setting unattainable goals. Although as noted in Chapters 3 and 8, not all cultures treat your direct communication with a patient as the appropriate means of dealing with a diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment decision, the appropriate spokesperson on behalf of the patient expects honest reassurance. Even then a more general expression of reassurance must be directed to the patient. For example, you may be able to offer reassurance about ways to cope with a changing body or about resources available to help him or her adjust to the new situation.

Chapter 6 recounts some major ways that life’s “slings and arrows” can shake one’s confidence in the way the world will respond and one’s certainty about what is reasonable to expect in the future. Reassurance is a powerful bridge-building beam, giving the patient confidence to rely on your word and think differently about his or her situation. The act of reassuring requires offering information that you can stand behind with certainty yourself, however minimal an effect you believe it will have on the patient. Reassurance may also take the form of your willingness to respond to difficult questions about areas that are causing anxiety for patients or their families.

You can use these personal experiences with confidence they will help guide you when you are faced with patients’ or family’s worries. When your attempts at reassurance are unsuccessful, use your own experience of when others’ attempts to reassure you failed. That can help you become aware of what might be going on in the mind of the patient. Further gentle probing may help to uncover the patient’s cause for concern and give guidance to the direction your reassuring words or gestures should take. At the very least your reassurance that you are trying your best to work on their behalf in this difficult time for them is always appropriate. Your creativity about how to retain or regain their confidence in themselves and the relationship must be an intentional part of your work plan. Overall, in your practice you will find that the time and activities you devote to reassurance will be as varied as patients themselves, but it will always be worth your effort to express your respect in this manner.

Integrity in Words and Conduct

Integrity comes from the root integritas, meaning “wholeness.” The cultivation of integrity is the commitment you make to yourself to temper your attitudes and conduct so that patients can experience a high level of consistency between what you say and what you do. They can observe fittingness between their needs and your demeanor and actions, providing the evidence they need for them to confidently place their trust in you.5

That attitudes and actions must be consistent with your reassuring words for professional closeness to develop is illustrated in the novel I Never Promised You a Rose Garden: The ward administrator tells Deborah, “It [the cold pack] doesn’t hurt—don’t worry.” Those words sound like words meant to generate reassuring comfort and Deborah’s willingness to cooperate with the health professional’s plan. However, Deborah, who is undergoing treatments in a psychiatric hospital and is frightened of what has already been done to her in the name of treatment, has exactly the opposite response. She thinks, “Watch out for those words . . . they are the same words. What comes after that is deceit.”6 Her situation illustrates that the words meant to be reassuring did not have the intended effect of engendering her confidence in the health professionals, because in the past, their conduct was not consistent with their words.

Integrity is not a character trait that only patients with long-term relationships with health professionals count on. Alice Trillin, the author of the quote at the beginning of this chapter, was on high alert from the moment Dr. Kris began his examination. He won her confidence in a one-time interaction.

The patient’s reliance on the professional’s integrity also extends to his or her experience with teams. Teams were first designed to help coordinate care so that the patient could experience a kind of collective integrity across the system. However, today sometimes the patient’s encounter with multiple members of a team breaks down confidence that there is “a plan” shared across units and among team members, and the patient experiences a fragmentation of services. The good news is that “[t]he culture of team care is a culture of interprofessional communication, with constant heads-ups and inquiries about what ought to be done with patients. In that sense, the culture of team care approximates the best that ethics seeks when it joins the team to help create the most humane and encompassing solutions(s) to the problems(s) at hand.”7 The potential for professional closeness is knitted into the fabric of teams, but in the end each individual on the team must strive to be sure that his or her own and the team’s integrity is at work to help ensure that the patient’s confidence is well placed.

Tease Out Transference Issues

The psychotherapeutic notion of transference can help you understand certain kinds of behavior some people might exhibit toward you when you enter into a professional relationship with them. Transference has its root in the theories advanced by Sigmund Freud and further developed by other psychologists who employ this term to convey the process of shifting your feeling about a person in your past to another person.8 A young man, angry that his father “ruled with an iron hand,” might conclude, “Here it comes again!” and respond aggressively to the health professional as soon as he is reminded of his father. One of the authors knows a male nursing student who prepared extensively and carefully to provide care to his first obstetrics-gynecology patient. A part of the clinical evaluation was to conduct a personal exam on her. Upon entering the patient’s room he said, “Good morning. I’m a student who is going to be your nurse today and I will be examining you.” The patient took one look at this bearded, 6-foot-plus student and said, “Oh, no you’re not! You look too much like my son, honey!” His supervisor, who had just stepped into the room, caught this woman’s reaction and judged that to disregard the patient’s discomfort would be a sign of disrespect. Instead she used the occasion as a teaching moment with the student, explaining that this type of transference sometimes happens. Everyone was relieved that this patient was reassigned to another student nurse.

Transference can be negative or positive. A negative transference interferes with trusting the support beams necessary for venturing confidently into a relationship. Examples are the aggressiveness of the young man and discomfort stimulated by the similarity of the student to the woman’s son. For reasons patients sometimes cannot identify or express, their comfort level is low and guard is up. At the other end of the spectrum, positive transference, the good feelings a patient transfers to the health professional, can promote a well-working relationship.

It is not always easy to tell whether the transference will create a problem. A young nurse caught a new male patient staring at her. Finally, he shook his head and said, “Man, I could have sworn my first wife walked in when you came into the room. The resemblance is startling!” Of course, this raised some questions—and the woman responded by saying, “Well, is that a good or bad thing?” He said, “Both!” So she was still in the woods on this one. She felt she had no choice in this case but to continue with the patient, watching for further signs that this man’s association seemed to be affecting his responses and their relationship. (There were none, and the matter never came up again.)

The patient is not the only party in the relationship who experiences transference. Countertransference, the tendency to respond to a patient with associations of others in one’s life, takes place every bit as often. A health professional may transfer feelings to the patient on the basis of name, physical appearance, voice, age, or gestures. Any one of these can increase the chance of countertransference. It is up to you to be self-aware about such associations and adapt your behavior to correct for any negative or other troubling responses you think might be issuing from your mental association of the patient with someone in your past or present relationships.

At the same time, total neutrality is not required. If you have served on a jury, you know that the lawyers try to select jurors whose past experiences and associations do not in any discernible way come into play when the facts of the case and the identification of the defendant and plaintiff are made known. A less rigorous standard is acceptable in the health professional and patient relationship. What is necessary for maintaining a respectful relationship with a patient is to be aware that transference and countertransference take place and try to be aware of how they might affect the interaction. It may not be possible always to identify the person whom the patient is “seeing” in you or you are “seeing” in the patient.9

Distinguish Courtesy from Casualness

You might think that showing common courtesy to patients is such an obvious component of respectful interaction that it need not be discussed. However, nothing is too basic or obvious to consider if it provides a support beam for you and the patient as you bridge the gap between you and define what your relationship will look like. You can begin to see its importance in the simple dictionary definition of courtesy as “courtly elegance and politeness of manners; graceful politeness or considerateness.”10 It goes beyond “minding your manners” in a superficial sense because it requires doing so with dignity in the way you go about being polite. Patients take their initial cues about whether they matter as people from the courtesy they receive when they first come through the door (or, in the case of home health care, you go through theirs). Although we strive to go beyond courtesy to deeper understandings of care in the health professional and patient relationship, the patient’s first, and often lasting, impression is connected to common courtesies they receive (or do not receive) from you. In this regard the work environment works best when it is a “consumer-friendly” environment.

As with many aspects of respect, you cannot generate a welcoming, courteous environment on your own. In almost every instance you will be a member of teams that schedule patient appointments, keep patients informed, collect fees, work toward making a diagnosis or carrying out a treatment plan, and conduct discharge or follow-up activities. But you can do your part, both personally and as a model for others. For example, common courtesies in an ambulatory care clinic include:

![]() greeting a person warmly and by name, introducing yourself and your role;

greeting a person warmly and by name, introducing yourself and your role;

![]() providing a safe place for them to hang a coat or umbrella;

providing a safe place for them to hang a coat or umbrella;

![]() offering assistance with mobility challenges and completing forms;

offering assistance with mobility challenges and completing forms;

![]() keeping the patient (and family member) informed about delays or necessary changes;

keeping the patient (and family member) informed about delays or necessary changes;

![]() being sure privacy is honored; and

being sure privacy is honored; and

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree