CHAPTER 4 Professional identities and communities of practice

USING THEORIES TO INFORM EDUCATION METHODS

Example: When teaching a novice health practitioner a new clinical skill, it is important to ensure there is an opportunity for a shared discussion about the new skill or ability. The shared discussion should encompass the educator’s goals and expectations; the key learning objectives and the student’s understanding and experience of the new learning event. Where relevant, the discussion should also encompass broader factors influencing the learning event based on the constraints and opportunities afforded by the particular clinical environment and people involved. To increase the effectiveness of learning in clinical education contexts, the expectations of learning and key educational outcomes should be discussed by both the educator and the learner.

Introduction

Clinical placements are fundamental to the educational experience of entry-level professionals. They are places where all students are inducted into the conversations of the health profession and begin to create their professional identity. Clinical placements, as a form of experiential learning, place demanding expectations on students. They are expected to demonstrate, often in unfamiliar situations, professional personae encompassing the application of technical knowledge and skill in site-specific contexts. Under direct supervision they are assessed for their ability to make responsible, safe and effective decisions about client welfare despite being at the intersection of various contingencies and necessities, initially only vaguely sensed (Webb 2004).

This chapter explores the idea that clinical placements and clinical practice for health professionals occur in communities of discourse. It seeks to illustrate a conceptual scheme that allows researchers, educators and students to follow the unfolding episodes of everyday life in clinical practices in new and illuminating ways. In this chapter we use two main theoretical frameworks as central anchors around which the importance of language and professional discourse are developed as mediums for clinical education learning. Our starting point is Vygotsky’s (1962) conception of the person in an ocean of language, in intimate interaction with others, and in the flow of public and social cognition. From this discussion we move to the theoretical framework of Positioning Theory to provide a conceptual platform to underpin the dynamic nature of learning relationships within clinical healthcare settings.

Experiential learning

Experiential learning is not a new concept. Dewey (1933) wrote influentially about the relationship between experience and learning. His main thesis was that cognition is an interpersonal construct developed through language. Later writers, like Schön (1983, 1987) have drawn on Dewey’s work to ground professional learning in rational reflection on one’s practices. Discussions about the nature of different forms of knowledge suggest truth and knowledge may be revealed in the practical consequences of an action or investigation (Gustavsson 2004). In this chapter, our central theme is that clinical practice and learning professional skills in clinical placement settings is a social act and not simply learning a professional role as a bundle of behaviours—like reading an instrument accurately. In proposing this argument, we rely on authors such as Vygotsky (1962), Wittgenstein (1953), Harré & van Langenhove (1999) and others, who have argued that mental life presupposes the giving of and asking for reasons for what we think, feel and value. This means, in a practical sense, that a novice’s actions are indissoluble from their speech and constituted in communities of practice in normative rather than causal connections.

Application of Vygotsky’s principles to clinical education

Vygotsky (1962) placed great emphasis on the role of language, not just as an attribute of individuals, but rather as the medium of interpersonal conversations. In these conversations, cognitive problems are solved and cognitive tasks performed. By appropriating or ‘taking on’ the discursive means in a community of practice, the individual becomes a competent individual performer. By appropriation we are suggesting that the routine nature of professional practice and knowledge needs to be integrated with the reflective and emerging thoughts of the novice, to ensure that there is a level of consistency and understanding between the thoughts and language of the novice and those of their peers.

In new clinical contexts, novices’ actions lack coherence in the local professional culture to whose membership they aspire. According to Vygotsky (1962), language and thought are two streams, one social and the other individual, which flow together in the higher cognitive functions, such as reasoning, deciding and remembering. Vygotsky introduced the idea of the acquisition not only of material tools but of cognitive tools, symbolic systems of which the most important was language. Vygotsky’s view is that language is the mediating tool of all higher order cognitive functions, and it is in the conversations in the family circle and among one’s peers that psychological development occurs.

The key to Vygotsky’s psychology is the idea of a kind of ‘psychological symbiosis’ where the senior member in a relationship scaffolds the learning of the junior member. Vygotsky (1962) proposed that every cognitive function is a joint project between the senior member and the junior member, where the junior member appropriates the new knowledge as their own. Although Vygostsky’s model was traditionally applied to childhood cognitive psychology, it can be extrapolated to adult learning situations. Understanding the learning process in symbiotic relationships is highly relevant to the learning that occurs in clinical placements. For example, when a novice is confronted by a task beyond their capabilities, they may try to perform the task but fail. Close by is the clinical educator, more able. The clinical educator, realising what the novice is trying to do, fills in the missing moves needed to complete the task successfully. The novice copies the supplementary moves next time they are confronted with a similar task. At the beginning of this process, the task and the novice’s capabilities are what Vygotzky calls the ‘zone of proximal development’ (ZPD).

There is a direct link here to clinical education pedagogy. Inter-psychological functioning between student and educator must be structured so as to enhance the development of intra-psychological functioning in the student. Feedback conversations form a prime example of this inter-psychological functioning between student and educator. In clinical practice the student demonstrates their skills and explicates their thinking, and the clinical educator evaluates these practices in relation to norms of practice through the provision of feedback. There is an expectation that the student will, in turn, appropriate this new information produced in feedback conversation, and that the transformation will be evidenced in their future practice. ‘Instruction in the zone of proximal development “calls to life in the (novice), awakens and puts in motion an entire series of internal processes of development”.’ (Vygotsky 1962, p 71)

Learning through engagement: professional or personal practice knowledge

Vygotsky’s theories of psychology and their influence on the psychology of learning suggest that professional knowledge should not be reduced to practical or technical-based knowledge, but should incorporate the learner’s own experiences and interpretations. Eraut (1985) and Williams (1998) discussed professional knowledge as having three components. The first is propositional knowledge, derived from discipline-based theories and concepts or from bodies of systematic knowledge that are publicly available. The second is personal, tacit or dispositional knowledge acquired by experience, and the third is process knowledge consisting of knowing how to conduct the various processes that contribute to professional accomplishment, including how to access and make use of propositional knowledge. Based on these distinctions, they described professional knowledge as the holistic integration of propositional, personal and process knowledge. Indeed on the basis of the layered nature of professional knowledge, one might argue that it needs to be rescued for the novice from assumptions of a routine nature.

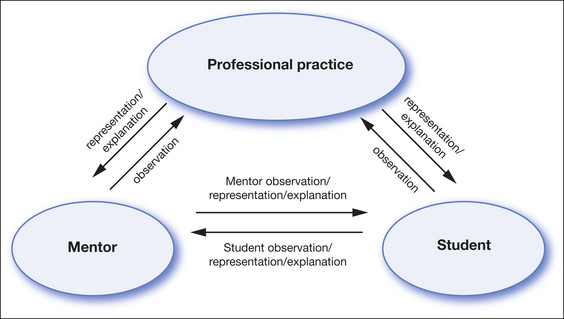

In the development of clinical knowledge for novices, both the social and physical environments mediated by a preceptor–educator provide important contexts for learning. However the personal context (that is, the novices’ views of themselves) are also highly significant. Clandinin & Connelly (1987) described this personal context as ‘personal practical knowledge’. In order to develop, it requires both private and public reflective thought in and about practice, and not just a process of direct transmission of information from a mentor. Figure 4.1 illustrates this concept of teaching–learning that we are promoting in this chapter.

Figure 4.1 A social constructionist model of clinical teaching and learning

(adapted from Webb 2004)

Pickering (1990) is another author who, like the more theoretically based Vygotsky, discussed the nature of the interpersonal relationship between students and educators as important to learning. She suggested that learning that occurs through relationships draws on cognitive knowledge; knowledge gained through prior experience and as an outcome of reflection on that experience through personal action. From this basis, enactment or practical experience should ideally provide the context for the development of understanding of competing perspectives. These perspectives include the proper technical management of a patient’s condition and clarification of how normatively based or discipline specific and rule-based reasoning relates to individual client needs.

Reason and Heron (1986) observed that professional experience enables knowledge to be gained through encounters with others, through a practising of skills as one engages in professional activities and associated reading and reflection. The encounters may be direct, as in being given direction or observation, or they may be indirect, such as through conversation. But in all cases they are mediated by previous knowledge and the intentions of the persons involved. They most often contain an affective element indicative of being in relationship. Bateson (1979) similarly argued that clinical learning is a holistic process that has affective, cognitive and conative features.

The following quotes are derived from the work of Webb (2004) whose research explored how physiotherapy students develop professional identity through conversations with others. The data illustrate the integral nature of students’ personal frames of reference and thoughts on their learning experience and outcomes. In the quotes, pronouns are bolded as a means of highlighting personal agency (Muhlhausler & Harre 1990).

Well, initially I sort of treated her like as a supervisor and I was like a student type thing, I think I was waiting there for her to give me some information at first and that’s why I think I didn’t go very well at the beginning … later on we didn’t concentrate on just my learning then because we started, more towards sort of like a colleague type relationship afterwards, because I was actually progressing and she was happy and she was confident in me and I was confident. (Webb 2004, p 114)

Well in the clinics I hope to be able to interact more, like observe other clinicians. And sort of learn from their behaviour and learn from their actions. Just like as to know what is right and what is wrong and what’s appropriate and what’s not appropriate at certain times. (Webb 2004, p 26)

Student expectations

Students have their own expectations of clinical practice. For example, they expect in their placements to make the transition from an isolated to a collegial existence. They expect to be accepted as a person, to get on well with significant others in the clinical situation, to be helped to perform well, to pass any assessments and make a recognised contribution. They expect to successfully put into practice what they feel they already know, in addition to learning new aspects of practice. Many emotions come with these expectations of self and of others. As Schatzki (2003) observes, in clinical practice placements, students expect their professionalism to be born, to unfold and to develop.

Some important implications of these expectations are that students rely on their prior academic studies to have taught them the authentic scientific language required in clinical practice. This will allow them to be able to communicate effectively and authoritatively with clinical educators, patients, their families and other professional colleagues, and to be recognised for these skills. However the language of practice is new to many students and has its own implicit local rules and cultural uses that need to be learnt. Webb (2004) found the process of mastering this implicit knowledge is complex for most students, particularly when communicated in a second language and culture. Crucial moments in becoming a professional are often couched in successful or unsuccessful moments in conversational interactions that are not limited to words in clinical settings.

Learning and professional identity formation is strongly influenced by the psychological positioning, institutional practices and societal rhetoric of the local discourse community. The ability of the individual student to locate themselves within these social episodes is complex and requires an understanding of both the explicit and the implicit rules and practices (Webb 2004). These implicit rules or norms are often embodied in ‘second nature’ practices grounded in local cultural assumptions that are rarely scrutinised.

The claims discussed previously by Vygotsky and others are that if local cultural assumptions and professional identity are not carefully scrutinised or made explicit and combined with students’ expectations arising from their own cultural assumptions and learning expectations, then the learning process may be less effective. The cultural psychologist Ratner (2000) also endorses these claims through his criticism of the dominant individualistic view of cultural agency that often frames professional education in universities. He claims that Western university courses implicitly teach ‘individual agency’ and that individual acts are considered to be the most significant in the learning process. Related to this view of learning and contribution to a societal group is the idea that individual constructions of personal meaning are more creative and profound and that personal-social virtues, such as ‘adaptability’ or ‘perceptiveness’, are often viewed as individual constructions.

Through this critique, Ratner contends that the main problem with an individualistic view of cultural agency is that it may ‘silence’ clinical conversations of those students who do not share the dominant culture (p 414). Ratner (2000, p 415) also observes that ‘institutional practices are not simply suggestions or meanings that can be ignored with impunity. Institutions are entities which structure people’s psychology by imposing rules of behaviours, punishments, rewards etc. They are controlled by a group of people and are not negotiated by individuals’. Ewing and Smith (2001, p 16) argue further that the novice’s aspiration for community membership is also bound to their biographies, their own storylines about ‘doing, knowing, being and becoming’. Practice is about self-improvement with and for other people within a purposeful informed ethical and aesthetic framework. These views support the importance of the central theme of this chapter, that student learning cannot effectively take place from a position of passive transmission of views from an educator to a student. There needs to be a recognition and active steps taken to integrate the personal, the cultural and the institutional.

Novices expect to be able to transform their theoretical knowledge into explicit practice knowledge. They expect opportunities to discuss with others their emergent personal knowledge in critical areas of practice, to have their position supported or refuted. They expect community recognition from, as well as accountability to, significant others. From these expectations, interpersonal relations provide a means of entering into communal forms of remembering, deciding and problem solving.

Among the most important types of communal obligations are rights and duties and their distribution in the clinical community. Students expect to participate in this local moral order; that is, to fully explore their rights and duties in the clinical community. Through this need for a more engaged style of learning, we argue that the evolution of the profession and the transformation of organisational capacity in clinical communities depend on how well students understand their own agency in this dual praxis of exercised rights and duties. This understanding is influenced by the opportunities they are given to join or integrate with the professional community. This theme is developed further here and is elaborated in Chapter 7 in the evolution of professional reasoning.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree