Chapter 12 Professional frameworks for practice in Australia and New Zealand

Learning outcomes for this chapter are:

1. To describe current and evolving professional frameworks that guide midwifery practice in Australia and New Zealand

2. To describe the links between definition and scope of practice of a midwife, philosophy, code of ethics, and standards for practice with midwifery standards review and recertification (New Zealand), and continuing professional development and midwifery practice review (Australia)

3. To articulate an understanding of the term ‘professionalism’ and differentiate between ‘old’ and ‘new’ professions

4. To articulate differentiations in the development of the midwifery profession in New Zealand and Australia, with respect to history, role, functions and structure

5. To differentiate between midwifery regulation in New Zealand and midwifery regulation in Australia, and express an understanding of regulatory principles in common

6. To describe the role and function of the Midwifery Council of New Zealand and the various regulatory authorities for midwifery in Australia including the transition to a National Registration and Accreditation Scheme for the Health Professions in July 2010

7. To explain the relationship between regulatory and professional frameworks and their application to midwifery practice.

This chapter outlines current and evolving professional and regulatory frameworks guiding midwifery practice in Australia and New Zealand. While professional frameworks for midwifery arise from the profession itself, regulatory frameworks reflect societal understandings of midwifery and wider interests than those of midwifery alone. Regulatory frameworks provide the statutory boundaries for midwifery practice and define the extent of professional autonomy each state affords to midwifery. This chapter explains the relationships between regulatory and professional frameworks in both countries, and how these frameworks affect midwifery practice.

INTRODUCTION

As a healthcare profession, midwifery in both Australia and New Zealand is governed by legislation that determines, to a greater or lesser extent, the scope of midwifery practice, the level of midwifery autonomy, processes for entering the profession (registration), expected standards for practice (competencies), and mechanisms for accountability and regulatory control. The purpose of this regulatory framework is to ensure the safety of the public by ensuring that midwives are appropriately qualified, competent and safe to practise midwifery. The legislation reflects society’s understanding of and assumptions about midwifery at the time the legislation was enacted. The effect of such legislation is to determine how midwifery interfaces with other providers of maternity services, how midwifery fits within the structures of maternity and healthcare services, and the extent of its professional jurisdiction. Particularly in the case of Australia, regulatory legislation does not necessarily reflect current midwifery practice or, indeed, women’s views of the kinds of midwifery services they wish to receive. It may well reflect the interests of other professional groups such as medicine, or of the state, in determining the direction of maternity services. Indeed, ‘as both a licensing authority and a source of funding, the state can enhance or diminish the control that an occupation or profession has at any given time over the provision of particular services’ (Tully 1999, p 3).

PROFESSIONS AND PROFESSIONALISM: WHAT DO THEY MEAN?

Professionalisation can be considered ‘the process by which an occupation moves toward a special form of control called a profession’ (Aydelotte 1985, p 127). In addition to laying claim to a special knowledge base that is socially sanctioned, and deriving economic benefit from the application of this knowledge, there is also an active political dynamic and legal legitimation of any claim to professional status that has led to the assertion that professions are the creation of a ruling class. The sociologist Elliot Friedson, in defining the attributes and characteristics required for full professional status in relation to the medical profession, advanced this view, stating:

A profession attains and maintains its position by virtue of the protection and patronage of some elite segment of society which has been persuaded that there is some special value in its work. (Friedson, cited in Ehrenreich & English 1973, p 47)

In other words, a profession uses its knowledge base as ‘an ideological cover in its struggle for power and status’ (Tully 1999, p 30). A profession’s knowledge base is contingent on the complex interactions that take place between professions, the state and client or consumer groups, and thus is highly variable (Tully 1999).

Abbot picked up on the dynamics of interactions between professions in his development of what he called the ‘system’ of professions (Abbott 1988). Abbott identified professionalism as a system of interprofessional competition that focuses on disputes over jurisdiction. He defined ‘jurisdiction’ as the link between a profession and its work, and argued that it ‘is the history of jurisdictional disputes that is the real, the determining history of professions’ (Abbott 1988, p 20). A profession’s work is the control of tasks.

The tasks themselves are defined in the profession’s cultural work. Control over them is established by competitive claims in public media, in legal discourse and in workplace negotiation. A variety of settlements, none of them permanent, but some more precarious than others, create temporary stabilities in this process of competition. (Abbott 1988, p 84)

Gendered professions

Divinity, law and medicine are three long-standing and traditional professions. Each group has a long and entrenched history of patriarchal tradition in Western societies and has attained the attributes of a profession described above. It is well documented that throughout their histories, each has sought to exclude women from entry or from the professional societies and organisations in which members exercise political influence, or has marginalised women to non-lucrative and less-prestigious areas of practice. This behaviour needs to be considered in the context of the historical control and cultural views of defined sex roles in Western industrialised societies, whereby the female sex role was considered to be incompatible with that required for professional achievement (Speedy 1987). For instance, medicine extended its social and legal legitimacy as the dominant healthcare profession during the 19th and 20th centuries, aided by the ideals and activities of Western imperialism, the rational doctrines of the Enlightenment and the principles of modern mechanisation (Grimshaw et al 1996; Willis 1983). Synchronously, midwifery was downgraded and/or made illegal in many Western societies, in the face of the new licensed professional (predominantly male), specialist medical practitioner, the obstetrician and gynaecologist (Anderson 2002; Donley 2002; Finklestein 1990).

While the improved status of women in contemporary Western society has enabled some to be admitted into the traditional professions, issues around sex differences and power dynamics remain. Men continue ‘to control the means by which their particular perspectives are privileged, through their control of political, religious, and literary discourses’ (Torres 1992, cited in Shachar 2001, p 4). In relation to childbearing, Lane (2002) and Reiger (2001, 2003) show that the scientific paradigm and its attendant consequences is now firmly institutionalised in law, medical recruitment and clinical practice in contemporary Australian society, including mainstream models of care sponsored by the funding mechanisms of the modern nation state. While the medical discourse of childbirth is being challenged in New Zealand by the development of a midwife-led and women-centred maternity system, it is still deeply entrenched, and the maternity service still reflects the global phenomena of medicalisation and technological intervention that characterise every Western society (Pairman & Guilliland 2003; Guilliland & Pairman in press).

Tully (1999) argues that a more useful way of understanding the relations between gender and professionalising activity is to conceptualise gender as a resource rather than as a relation of social domination or inequality. Her examination of midwifery in New Zealand shows how midwifery was able to use the gender of its practitioners as a resource in a context where women were demanding more ‘women-centred’ care and the state had given priority to the women’s agenda. Tully contends that New Zealand midwifery deliberately reconstituted itself as a feminist form of professional practice. Central to this practice is the concept of a ‘partnership’ between midwives, as female healthcare professionals, and women who share their understanding of birth as a normal life event.

In positioning midwives and birthing women as ‘partners’ who shared responsibility for the pregnancy/birth, midwifery leaders drew on feminist understandings of the importance of women taking control over their lives and health in general, and their reproductive experiences in particular. Feminist concerns about issues of responsibility, control, empowerment and choice were put at the centre of midwifery’s definition of itself as a profession with a ‘moral obligation to work in partnership with women’. (Tully 1999, p 49)

‘Old’ and ‘new’ styles of professionalism

The attributes that characterise a profession have been described as

However, a profession’s social power is even more important than its expertise or knowledge, or the commitment of its members. This social power is achieved through a social mandate for practice, and the social mandate comes from political action.

Ehrenreich and English reminded us of the contradictions inherent in professional status when they stated:

We must never confuse professionalism with expertise. Expertise is something to work for and to share: professionalism is—by definition—elitist and exclusive, sexist, racist and classist. (Ehrenreich & English 1973, p 42)

These notions of professions as ‘expert’ with a rational, scientific and masculinist approach to knowledge characterise ‘old’ style professionalism, which continues to define dominant professions in Western industrialised societies. For many midwives, the characteristics of ‘old’ professions are antithetical to midwifery because they are seen as separating midwives and women from each other, and midwives have asked why midwifery would want or need to be a profession (Cronk 2000; Wilkins 2000). In contrast, the New Zealand midwifery model of midwifery partnership provides an example of ‘new’ professionalism (Guilliland & Pairman 1995; Pairman 2005; Tully 1999). This latter model has been described as characterising the ‘new midwifery’ of the future, in which knowledge about the body is constructed as the outcome of relationships and interactions between people (Lane 2002; Page 2003). The characteristics of old and new professionalism can be differentiated as: mastery of knowledge versus reflective practice; unilateral decision processes (patient as dependent, colleagues as differential) versus interdependent decision processes (patient empowered, colleagues engaged as equals); autonomy and self-management versus supported practice teamwork; individual accountability versus collective learning, responsibility and accountability; and detachment versus engagement (Health Workforce Advisory Committee 2005).

We move on now to explore midwifery’s approach to professionalism in both Australia and New Zealand.

Midwifery as a profession in Australia

Midwifery in Australia is in a state of transition and at this stage does not reflect the attributes of either ‘old’ or ‘new’ professions (Barclay et al 2003).

Influences of competing discourses of childbearing

Understanding the evolution of a professional framework for midwifery practice in Australia in the 21st century is contingent on examining and understanding the historical, political, cultural, economic and race relations of Australia’s early foundation as a colonial settlement of the United Kingdom and its subsequent development into a modern nation state. These developments encompass the sociopolitical, professional and economic arrangements and relationships that underpin the evolution of its current healthcare infrastructure (Anderson 2002; Duckett 2000; Grimshaw et al 1996; Reiger 2003). Additionally, understanding recent critique of contemporary economic, political and cultural forces that have influenced government policy, including competing trends towards both market-driven healthcare services and institutionalised state-sponsored healthcare services, consumer and professional activism, and the women’s movement during the 20th century, is also vital in understanding influences on the future framework for professional midwifery practice in Australia (Barclay et al 2003; Donnellan-Fernandez & Eastaugh 2003; Maternity Coalition et al 2002; Reiger 2001).

Predominantly, mainstream Australian maternity services are fragmented into antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal spheres, and maternity care has been constructed within an industrial nursing framework whereby the midwife’s role is confined to a set roster and specified hours. This historical structural division of labour has created conflict among groups advocating an elitist, specialist, professionalising route for midwifery and those that place women at the centre of the decision-making process, such as ‘partnership’ models of midwifery in which care is part of the continuum of an established relationship (Reiger 2001). Within such a context, questions need to be asked about how and where professionalisation as a strategy for midwifery sits in relation to current discourses of birth as a social construct. This includes consideration of the emerging ethos of relationship between women and midwives being articulated as ‘partnership’ models of birth in countries such as New Zealand, where midwifery autonomy has been actualised in practice and is visibly regulated (Pairman 2005; Guilliland & Pairman 1995, 2010a, 2010b).

In examining the Australian history of childbearing, Reiger (2003) and Lane (2002) have analysed the evolution and construction of birth as the medicalisation of the body and of social life. Both authors propose that professionalisation has been a response to the state-sanctioned medical-practice monopoly in childbearing, including the historical subordination of midwifery as a branch of specialist nursing practice. This claim is further supported by recent analyses of midwifery history in Australia in relation to the role, education and regulation of midwives (Barclay 2008; Fahy 2007; Summers 1998), including contemporary Australian midwifery researchers’ claims of the practice of medical obstetrics on normal, healthy women as a form of ‘occupational imperialism’ to ensure ongoing medical strategic control and financial monopoly of maternity services. Twofold effects have been a national lack of access for consumers to midwifery-based services and the continuing lack of midwifery autonomy and job satisfaction, resulting in deskilling and increasing attrition rates from the midwifery workforce (Brodie 2002; Tracy et al 2000).

The sites where midwives have been able to practise autonomously in Australia, such as birth centres and home birth, have been limited and marginalised by barriers that include: a lack of state-sponsored policy frameworks and funding mechanisms; interprofessional rivalry and philosophical clashes with medical and nursing groups; and, since mid-2001, national withdrawal of professional indemnification arrangements for self-employed midwives despite continuing state-subsidised arrangements for the medical profession (Donnellan-Fernandez 1996, 2000; Donnellan-Fernandez & Eastaugh 2003). Although midwifery claims to be a profession, its professionalisation strategy is still in its infancy (Lane 2002). Lane (2002, p 30) suggests that ‘Midwives need to ask themselves how much autonomy they wish to exercise in their practice and how they understand the relationship between the body and society’. In common with the findings of Sandall (1997) in the United Kingdom and Lazarus (1997) in North America, her research leads her to advocate for diversity in models of midwifery practice, to suit ‘both women and a range of women’s needs’ (Lane 2002, p 39).

Australian Midwifery Action Project

The most recent comprehensive report on midwifery in Australia remains that of the Australian Midwifery Action Project (AMAP) (Barclay et al 2003). This project facilitated the collaboration of industry partners, researchers, relevant organisations and the wider community through an action-oriented research process. Over the life of the project, the primary outcome has been a series of publications investigating the service delivery, educational, policy and regulatory environments affecting midwifery nationally. Important secondary outcomes have been ‘to analyse and facilitate collaboration and communication across all of these sectors’, in addition to ‘informing the development of national and state initiatives to improve maternity services’ (Barclay et al 2003, p 61). The findings of AMAP are a legacy of the history of many of the forces identified above, and the report is significant in that it underlines barriers to the future of midwifery in Australia. Particularly problematic at the beginning of the 21st century is the national status of the midwife. In summary, this includes:

the lack of a coherent approach to the role of the midwife—the invisibility of midwives in policy, planning and regulation, and problems in contemporary midwifery education offered by schools of nursing. These include lack of symmetry between various stakeholders with regard to the role of the midwife; her sphere of practice, her skills, degree of professional autonomy and legal responsibilities form a singular and monolithic barrier to the emergence of a fully functional midwifery profession. The future potential of midwifery as a provider of primary healthcare to all women, regardless of designated medical risk status, rests on the capacity of educational, regulatory and service institutions to mobilise a unified vision of midwifery practice and the requisite skills and legal framework to achieve it. (Barclay et al 2003, p 57)

Professional status

Educational process

While a unique body of knowledge and skills in midwifery is asserted in the ‘International Definition of a Midwife’ (ICM 2005) and accepted by the Australian College of Midwives, recent mapping and critique of inconsistencies and minimum practice standards in midwifery education programs in Australia have highlighted both a lack of opportunities for students to participate in midwifery models, and the fact that current assessment regulations for midwifery fall well short of those required by the regulation bodies of other industrialised countries (ANMC 2004; Leap et al 2002). These findings are hardly surprising, given Australian midwifery’s history, education infrastructure, resources and industry/labour force expectations of a skill set and accompanying set of socialised relationships that have been constructed as ‘add-ons’ to specialist nursing practice (Donnellan-Fernandez 2000).

Body of knowledge

Interviews by Lane (2002) with Australian midwives showed that midwifery is not a static, discrete body of knowledge, and that midwives cannot be classified into discrete obstetric-assistant/medical models or professional/independent midwifery models. Rather, most could be classified as ‘hybrid’ and reflecting the needs of a variety of practice settings rather than a model determined by midwifery.

Discretionary authority and judgement

While the Australian College of Midwives (ACM), as the peak ‘professional’ body for midwives in Australia, has articulated national standards for midwifery practice and education, it currently has no statutory mandate to enforce these standards in law in all Australian states and territories. Nationally consistent professional midwifery educational and practice standards include: ACM Standards for the Accreditation of Bachelor of Midwifery Education Programs Leading to Initial Registration as a Midwife in Australia (ACM 2006); ANMC National Competency Standards for the Midwife (ANMC 2006); and more recently ANMC Code of Ethics for Midwives in Australia (ANMC 2008a), ANMC Code of Professional Conduct for Midwives in Australia (ANMC 2008b), and ANMC’s Midwives: Standards and Criteria for the Accreditation of Nursing and Midwifery Courses Leading to Registration, Enrolment, Endorsement and Authorisation in Australia with Evidence Guide (ANMC 2009). Prior to July 2010 there was no national legislative framework, no discretionary authority and no regulatory jurisdiction that exercised consistency in applying national regulation standards to the profession of midwifery in Australia. In each of the six states and two territories of the Federation, nurse regulatory authorities have held legislative authority to regulate the practice of midwives and the profession of midwifery. Only over the past decade has legislative amendment been successfully intitiated in several jurisdictions to reflect their mandate as nurse and midwife regulatory authorities (NMRAs), with some states and territories continuing to ambiguously license midwives as nurses, waiving requirements for demonstration of specific currency or competence. This position is legislatively inconsistent with professional midwifery practice or regulation in other areas of the Western world, and inconsistent with the principle of regulation in the public interest (Brodie & Barclay 2001; Donnellan-Fernandez 2001).

From July 2010 this situation has changed as the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) National Registration and Accreditation Scheme for the Health Professions (known as NRAS; COAG 2008) took operational effect through the newly constituted Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia. This initiative was signed off by COAG in an intergovernmental agreement in March 2008. The national scheme, informed by the Productivity Commission Report of 2005, has commenced its structural enactment through the Health Practitioner Regulation Administrative Arrangements National Law Bill 2008 (Bill A), via passage in the Queensland Parliament on 13 November 2008. The National Agency and National Health Professional Boards established under the first-stage legislation were constituted in 2009, with further legislation (Health Practitioner Regulation National Law 2009, Bill B and Bill C) covering matters beyond the terms of the COAG agreement (e.g. registration, accreditation, complaints, conduct, healthcare and performance arrangements, privacy/information-sharing arrangements and dissolution of current separate state and territory jurisdictional boards) being them anticipated to fully operationalise the scheme nationally by the projected date of July 2010.

Cohesive professional organisation

Until the late 1970s, midwives in Australia were largely subsumed within nursing organisations. In 1979 a National Midwives Association was formed concurrent with an emerging professional consciousness. Subsequent incorporation and membership of the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) has seen the ACM develop over the past 30 years to become the accepted national organisation for midwives. In addition to shaping standards for professional midwifery practice it has developed educational programs, participated in health policy development and provided a significant information network for its members (Barclay et al 2003).

However, despite ACM articulation of comprehensive objectives (see the discussion of the role and function of the ACM later in this chapter), recent analysis indicates that the ACM has not yet achieved the same cohesion, public profile or political influence as some of its international sister organisations, such as the New Zealand College of Midwives and the Royal College of Midwives in the United Kingdom. Membership remains less than a quarter of midwives estimated to be currently practising, with the majority (who are employed by state and territory governments in public-sector hospitals) remaining members of the principal industrial body for nursing in Australia, the Australian Nursing Federation (Reiger 2003). In one jurisdiction, South Australia, the state branch of the industrial organisation has in 2010 changed its name to the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (SA Branch) to include recognition of its midwifery members.

Birth culture and institutionalisation

Despite current global evidence and policy that supports universal access for all healthy childbearing women to midwifery-led care (Hatem et al 2008; WHO 1996), the dominant, state-sanctioned birth culture in Australian society at the beginning of the 21st century remains that of institutionalised medicine (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care 1999; Maternity Coalition 2008; Maternity Coalition et al 2002). This culture is characterised by ongoing state sponsorship of medicine, including over-representation of techno-industrial models of ‘professional’ practice which view the birthing body as a ‘machine’ and generate profits or health-funding outcomes that are defined in a market-driven economy (Davis-Floyd & Sarjeant 1997; De Vries et al 2001; Lake & Epstein 2007). In common with many other affluent, industrialised Western nations, in Australia this culture is entrenched at the level of government policy, funding and existing health infrastructure (AGPC 2004; Donnellan-Fernandez & Eastaugh 2003; Donnellan-Fernandez et al 2008; McCauley et al 2007; Reiger 2003; Tracy 2002).

Despite two decades of state, territory and national inquiries into birthing services in Australia, including accompanying recommendations expressing women’s repeated requests for ‘choice, continuity and control’ (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care 1999), there has to date been an ongoing vacuum in national government policy and political will to enable the funding, infrastructure and service-reform recommendations of these reports to be implemented (Maternity Coalition 2008; Maternity Coalition et al 2002). The National Review and Report of Maternity Services conducted by the federal government during 2008–2009 has offered the first sign of a coherent Commonwealth commitment to reforming maternity services in Australia (Commonwealth of Australia 2009).

Robust evidence demonstrating safety and rates of obstetric intervention in labour and birth remaining lowest among women experiencing care from midwives in public-sector models or birth centres in Australia has been available for over 15 years (AIHW 2007; Homer et al 2001a; Roberts et al 2000, 2002; Shorten & Shorten 2004, 2007; Tracy & Tracy 2003; Tracy et al 2006, 2007; Turnbull et al 2009). While some models of public-sector midwifery continuity of care have evolved over the past decade (Community Midwifery Western Australia 2006; Cornwell et al 2008; Homer et al 2001b; Nixon et al 2003; Power et al 2008; Scherman et al 2008; Tracy & Hartz 2005), most remain constrained to location in metropolitan areas and in their capacity to meet the demand for midwifery-led services. The norm for the majority of families is a culture of expensive, medicalised childbirth with less than 5% of women able to access midwife-led services (Donnellan-Fernandez et al 2008). Maternity care options for women living in regional, rural and remote areas of the country is limited to state-funded medical providers or, since the introduction of Medical Benefits Schedule Funding Item 16400 in 2006, employed staff who may or may not have qualifications and competency in the provision of maternity care providing funded services ‘on behalf of medical providers’. (Medical Benefits Schedule n.d.). In many instances access to local services and culturally appropriate services, particularly for Indigenous women, are non-existent or in limited supply (ACRRM et al 2008).

While most Australian state and territory governments have developed maternity frameworks or overarching planning documents (e.g. South Australia’s Health Care Plan 2007–2016; Maternity Services Review in the Northern Territory; Re-birthing: Report of the Review of Maternity Services in Queensland 2005 (Hirst 2005); Improving Maternity Services: Working Together across Western Australia, a policy framework 2007; Future Directions for Victoria’s Maternity Services 2004), over the last decade none has articulated comprehensive policy nor actioned wide-scale systematic reform for sustainable maternity services based on primary healthcare principles that enable and utilise the midwife working to the full scope of practice as defined in the International Definition of the Midwife. This remains in stark contrast to the New Zealand context, where more than 80% of women can access lead maternity care through a midwife via the legislated cover defined in the Primary Maternity Services Notice 2007 pursuant to Section 88 of the New Zealand Public Health & Disability Act 2000 (Ministry of Health 2007).

Recent developments including the Australian Health Minister’s Advisory Council 2008 paper Primary Maternity Services in Australia: A Framework for Implementation has renewed dialogue in relation to national maternity policy and healthcare services reform, as has the national maternity services discussion paper, review and final report Improving Maternity Services in Australia: The Report of the Maternity Services Review (New South Wales Department of Health and Ageing 2008; Commonwealth of Australia 2009). Additionally, the federal government is progressing policy consultation to develop a National Maternity Services Plan during 2010 that will be underpinned by principles articulated in the Primary Maternity Services Implementation Framework.

One of the most progressive Commonwealth government initiatives has been the introduction (and lates passing into law) of the Health Legislation Amendment (Midwives and Nurse Practitioners) Bill (2009), the Midwife Professional Indemnity (Commonwealth Contribution) Scheme Bill (2009) and the Midwife Professional Indemnity (Run-off Cover Support Payment) Bill (2009), underpinning reforms to fund antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care by ‘eligible’ midwives. This includes implementation of a government-supported indemnification scheme. While these Bills became federal laws in March 2010 they were highly contentious, drawing strong critique in both professional and public domains, and have generated two federal Senate Inquiries. The principal areas of contention were the lack of provision and direct exclusion of midwifery rebates, and indemnification for midwifery home-birth access outside current limited public-sector service options. Proposed regulations that will require ‘eligible’ midwives to engage in written collaborative arrangements with individual doctors have been critiqued as an attempt to veto the professional scope of midwifery practice in Australia. While from November 2010 ‘eligible’ midwives will be able to prescribe subsidised medications and to bill their services to Medicare Australia, until these outstanding issues are addressed by satisfactory government policy and systemic reforms that address funding and workforce challenges, women wanting to access midwifery care for home birth and midwives in private practice may have their safety, their access and their autonomy compromised (Wilkes et al 2009).

Redefining professionalism in New Zealand

The current status of midwifery as a profession in New Zealand is somewhat different to that in Australia. New Zealand midwives are an autonomous and distinct professional group. They were granted a social mandate for autonomous practice in 1990 through the Nurses Amendment Act and subsequently have established midwifery as the main provider of maternity services based on a model of autonomous caseload practice and midwifery partnership (Guilliland & Pairman 2010b). Largely through the influence of midwifery, New Zealand’s maternity service has been reshaped to a women-centred and midwife-led service in which each woman can access one-to-one continuity of midwifery care from early pregnancy through to six weeks postpartum, no matter what the course of her childbirth experience and which other providers need to be involved, and no matter where she chooses to give birth (Guilliland & Pairman 2010b; Pairman & Guilliland 2003). New Zealand midwifery, perhaps more than any other, most closely meets the International Definition of the Midwife by practising within the full scope of midwifery practice (ICM 2005; MCNZ 2004a).

For New Zealand midwifery, these achievements are the culmination of years of planned political and professional activity to bring about the necessary changes to legislation, to societal understandings of birth and midwifery, and to midwives’ understandings of midwifery as a profession that is deeply intertwined with women. The central tenet of New Zealand midwifery’s professional identity is that midwifery is the partnership between women and midwives (Guilliland & Pairman 1995; NZCOM 2008a; Pairman 2005). By constituting midwifery as ‘midwifery partnership’, New Zealand midwives have sought to replace traditional notions of professionalism with one in which relationships between midwives and women are negotiated and where power differentials are acknowledged and actively shifted from the midwife to the childbearing woman (Pairman 2005).

Although New Zealand has had a regulated midwifery workforce since the Midwives Act 1904, the scope of midwifery practice diminished as a result of increasing hospitalisation and medicalisation of childbirth from the early 1920s onwards (Donley 1986; Guilliland & Pairman 2010b; Mein Smith 1986; Pairman 2002, 2005; Pairman & Guilliland 2003; Papps & Olssen 1997). Women were encouraged to birth in hospitals to avoid the risks of puerperal infection in the home and so that they could access ‘pain-free’ birth. Claims by doctors that hospitals were safer than home were unfounded (Mein Smith 1986). That hospitalisation led to fragmented maternity care, loss of control for women and their families, increased medical intervention and use of technology, loss of confidence in women’s bodies, and increased fear of birth, has been well documented and is reflected throughout the Western world (Donley 1986; Donnison 1988; Kitzinger 1988; Mein Smith 1986; Papps & Olssen 1997; Tew 1990). Institutional organisation and power structures also affected midwives, who lost their one-to-one community-based practice with women to become ‘doctor assistants’ and ‘specialists’ in aspects of maternity care. By 1971, midwifery was no longer visible as a separate profession and was incorporated into nursing as ‘specialist nursing practice’. Legislative changes in 1983 and 1986 further undermined the definition and scope of practice of midwifery, which reached an all-time low, where only a handful of home-birth midwives remained practising in a way that bore any resemblance to the International Definition of Midwifery (Donley 1986; ICM 2005).

It was this near-demise of midwifery that led to its rebirth. In reclaiming their identity as separate from nursing, midwives used their professional group, the Midwives Section of the New Zealand Nurses Association, as a vehicle for political action. Initially this activity was focused on reclaiming the ICM definition of a midwife as a ‘person’ rather than a ‘nurse’ (as the Nurses Association had redefined it) and on separating midwifery education from nursing (Pairman 2002, 2005). However, midwives soon realised that their interests were divergent from those of nursing and could never be served by the (larger) nursing professional organisation. Midwives disbanded the Midwives Sections and in 1989 formed a separate midwifery professional organisation, the New Zealand College of Midwives (Donley 1989; Guilliland 1989; Guilliland & Pairman 2010b).

Maternity consumer groups were also active at this time, seeking to gain control over their birth experiences and to decrease the dominance of the medical model over maternity services (Strid 1987). These women had faith in midwifery and argued for a return of the autonomous midwife, who they believed would be more likely to share power with women through a more women-centred and normal-birth philosophy of practice (Dobbie 1990; Strid 1987).

A key outcome was that midwives recognised the benefit to themselves and to women of their political partnership, and they gave meaning to this partnership by incorporating partnership constitutionally into every aspect of the NZCOM. Midwifery ‘consciously recognises that the only real power base we have rests with the women we attend’ (Guilliland 1989, p 14). The active involvement of women in the New Zealand College of Midwives has continued to strengthen midwifery. ‘Women’s participation in the midwifery profession has given midwives a public, legal and socially sanctioned mandate for practice’ (Guilliland & Pairman 1995, p 19). This social mandate carries with it a moral obligation for the midwifery profession to provide the kind of service women want. The continued involvement of women (consumers) in the policy formation and processes of the NZCOM ensures that midwives uphold the needs and wishes of women.

Although not attracted by the traditional ‘power over’ model of professionalism, they recognised the potential benefit of professional autonomy. As Oakley and Houd (1990, p 114) contend, ‘the exclusion from childbirth of autonomous midwifery restricts the care options available to childbearing women and inevitably promotes the definition of childbearing as a pathological medicalised event’. New Zealand midwives and women believed that if midwifery autonomy were reinstated, then midwives would have the ability to once again practise within their traditional role as a guardian of normal birth (Strid 1987). Each midwife who worked in this way would be a ‘positive presence who focuses on the childbearing woman and the baby, with the knowledge and skills required, but also with a sensitivity and respect for the individuality and uniqueness of each woman and her choices for birthing’ (Strid 1987, p 15). Writers such as Barbara Katz Rothman supported these beliefs; she stated:

The determination to provide women and midwives with the opportunity to co-create new knowledge and understandings of childbirth that would lead to women regaining control and choice in childbirth, and to society once again recognising childbirth as a normal life event rather than an illness, was the impetus for political activity to reinstate midwifery autonomy. Through the experience of this political partnership, midwives were able to conceptualise a ‘new’ model of professionalism.

By redefining the professional–client relationship as one of ‘partnership’ in which each partner contributes knowledge and experience, it also embraces feminist criticisms of the hierarchical power relations inherent in the doctor–patient relationship and the consequent devaluing of women’s knowledge. (Tully & Mortlock 1999, p 175)

In recognising the knowledge and experience of women/clients as well as midwives, midwifery partnership does not afford midwifery expertise and knowledge the same epistemological priority it held in the ‘old’ model of professionalism (Tully 1999). In midwifery partnership, both midwives and women have recognised authority and the midwife’s role moves from ‘expert’ to ‘reflective practitioner’ whose task is to support, guide and accompany a woman within a more equitable, interdependent and empowering relationship (Tully 1999). In redefining midwifery practice as partnership, New Zealand midwives have differentiated midwifery services from maternity services offered by other providers and claimed jurisdiction over ‘normal’ birthing services. Thus partnership with women is an effective professionalising strategy for midwives (Tully 1999; Pairman 2005).

DEVELOPMENT OF THE MIDWIFERY PROFESSION IN NEW ZEALAND

Structure and functions of the New Zealand College of Midwives

The New Zealand College of Midwives (NZCOM; the College) is the professional organisation for midwifery in New Zealand. Established in 1989, the College has provided a mechanism for midwives to establish themselves as a profession separate from nursing. The College now represents over 90% of all practising midwives in New Zealand. Midwives’ commitment to midwifery partnership has meant that from its inception, women consumers have been members as of right and the constitution provides for regional and national membership by individual women and consumer groups. The consumer membership votes for four representatives to the National Committee from consumer organisations such as Parents Centre New Zealand, Home Birth Aotearoa, La Leche League and the Plunket Society. As the voice for midwifery in New Zealand, the College is involved in a wide variety of activities, both professional and political, to meet the needs of individual midwives, the profession as a whole, and birthing women as its partners and the focus of its interests, by working to maintain a strong and autonomous midwifery profession. The role and functions of the College are summarised in Box 12.1.

Box 12.1 NZCOM role and functions

The role and functions of the New Zealand College of Midwives are listed below.

| Professional practice advice and information | Professional development/standards | Quality assurance |

| Education | Liaison | Research |

| Communication and promotion | Legal advice and representation | Financial management/membership management |

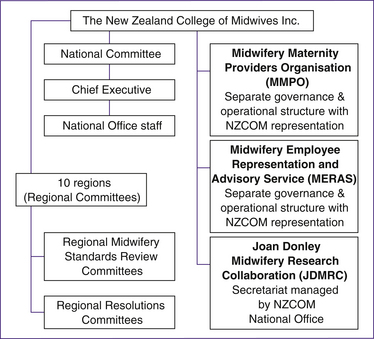

The College structure is simple (see Fig 12.1). New Zealand is divided into 10 regions, each with its own regional committee and governance responsibility. The chairpersons (all midwives) of each of the 10 regions are members of the National Committee, along with the four consumer representatives, two midwifery student representatives and two Māori midwife representatives. The President and the Chief Executive lead the Committee with support from two kuia or elders (Māori and Pākehā [non-Māori]). The National Committee meets three times a year to fulfil its governance role. An ad-hoc committee of the National Committee forms a Governance Committee that meets before each National Committee meeting to explore financial and other policy issues in depth, in order to assist and inform the National Committee decision-making processes. The College works in a non-hierarchical and women-centred model that includes extensive consultation processes and consensus decision-making. The National Committee employs the Chief Executive, who in turn employs the staff of the National Office. These staff, some of whom are midwives, carry out the day-to-day work of the College as represented in Box 12.1.

As it has evolved, the College has recognised the need for other midwifery-specific organisations to meet the business and industrial needs of midwives. Considerable thought went into the establishment of these organisations to ensure that their structure, functions and governance mechanisms did not become blurred with the College and dissipate the overall strength and unity of the midwifery voice. As shown in Figure 12.1, the College has created three separate but parallel organisations: the Midwifery and Maternity Providers Organisation (MMPO), the Midwifery Employee Representation and Advisory Service (MERAS), and the Joan Donley Midwifery Research Collaboration (JDMRC). Each organisation has its own governance structure and specific role and functions, and its links to the College are maintained through College representation to its governance structure and through the requirement for midwives to first be members of the College before they can access services from any of these organisations.