WHAT IS THE NMC?

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) is an organisation that ensures nurses, midwives and specialist community public health nurses provide high standards of care to their patients and clients. Qualified practitioners are registered through the NMC and the NMC has the right to suspend or remove practitioners from the register if it is proven that the practitioner is not safe, or does not behave in a professional manner.

The NMC also sets out guidelines and criteria for education and practice, gives advice to nurses, midwives and specialist community public health nurses, and publishes numerous publications to support good practice.

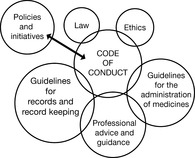

Among the NMC publications you will find most useful are the:

• Code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics

• Guidelines for records and record keeping

• Guidelines for the administration of medication.

These publications are important but they are also fluid and are updated regularly. They are available free – either on the NMC website or by post on request. You can search the NMC website for information on many different subjects and most of the NMC publications are available on the NMC website as a document file.

The NMC is accessible to practitioners and members of the public:

• Postal address: Nursing and Midwifery Council, 23 Portland Place, London W1B 1PZ

• Web address: http://www.nmc-uk.org

• Telephone enquiries: main switchboard: 020 7637 7181; registrations: 020 7333 9333; overseas application: 020 7333 6000; employers: 020 7631 3200; fitness to practise: 020 7333 6564; professional advice: 020 7333 6550; press enquiries: 020 7333 6557/6558.

Being a qualified nurse is a huge responsibility but the NMC has provided resources to help you. This chapter looks at those resources and how they support you in the responsible, competent and safe practice of professional nursing.

Throughout the chapter, I will refer to ‘patients’ and ‘nurses’. I am using these as general terms for clarity – for ease of reading – and not in any way to minimise or exclude any individual or group of professionals or members of the public.

Although the NMC Code of professional conduct is the most commonly cited, all of the NMC guidance is intended to lead your professional practice. The directives all work together. Use the other directives to help you understand your obligations under the Code of professional conduct.

|

OBLIGATIONS AND EXPECTATIONS OF THE PROFESSIONAL NURSE: THE NMC CODE OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT

The Code of professional conduct is there to explain what nurses do, in the hope that all nurses will live up to the expectations knowing that if they don’t, the NMC has the power to prevent them from practising as nurses. It sets a precedent and the ground rules. Basically, it outlines:

• The standard of practice and conduct expected of you as a professional nurse.

• What members of the public should be able to expect of a nurse, midwife or health visitor.

In plain English, the Code of professional conduct says:

“Everything you do as a nurse – the way you work with others, the way you behave and communicate, every action you take – should be done with the best interest of your patient in mind.”

As a nurse, the NMC gives you one guiding principle: You must be the kind of person who is able, in practice as a nurse, to put the patient first.

Respect the patient or client as an individual

Everyone, but especially vulnerable people, has the right to be treated fully and wholly as a person. No one person is greater or more deserving than any other. Age, race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, lifestyle, culture, social or economic status, political beliefs, physical or mental disability – it doesn’t matter. Every individual is equally precious and valuable. Your role doesn’t stop with just acting for yourself, in your own practice. The Code of professional conduct says you must ‘promote and protect the interests and dignity of patients …’ . This might mean speaking up for a group of people by challenging protocols or practices. We must respect our patients and make sure others do as well. This could mean challenging the lack of information for a certain group, or that the criteria for a particular service unfairly discriminate against a group.

Respecting individuality means letting people make decisions for themselves. You have an obligation to provide people with information about health and social care and how to access care and support, but you can’t make decisions for people as long as they are competent to make those decisions for themselves. It doesn’t matter if you agree or if you think that they might have a better quality of life if they do what you tell them. Part of being a nurse is recognising that people have the right to live the life they want, as the Code of professional conduct says, ‘within the limits of professional practice, existing legislation, resources and the goals of the therapeutic relationship’.

Respecting people also means having boundaries. You also can’t ever exploit your role as a nurse – you can’t use the fact you are caring for someone to gain at their expense. That gain might be physical, social or economic – no matter how, it’s wrong. Benefiting at a patient’s expense is abuse, because your job is to take care of people, not have them take care of you.

Obtain consent before you give any treatment or care

The Code of professional conduct states:

“When obtaining valid consent, you must be sure that it is:

• given by a legally competent person

• given voluntarily

• informed.”

Every person is legally competent unless a ‘suitably qualified practitioner’ decides that they are not. Competence to make a decision can vary depending on what the decision is: someone who is not competent to consent to heart surgery might be competent to decide they don’t want to take a bath. Being legally competent means the person can understand what the treatment is, what the consequences are, and make a conscious choice.

If it’s an emergency and the patient can’t tell you what he or she wants, you are expected to do whatever is necessary to preserve life. You can’t use these circumstances to over-ride what you know the patient would say if he or she was able. Sometimes individuals will have left advice with family or friends, or left a document such as a ‘preferred place of care’ (a document that allows people to express their wishes for end-of-life care) stipulating their wishes. You can look at the patient’s past history: if that person has said ‘no’ several times to a procedure, you should know in your heart that, if you were able to ask, he or she would probably still say ‘No’. Several years ago there was a story in the news about a hospital near my home in America. A patient who had a religious objection to a blood transfusion was in A&E bleeding to death. The patient refused blood, even though he knew this meant he would die. As soon as he became unconscious, a doctor started a transfusion. Technically, this fitted the criteria – it was an emergency and it was to preserve life – but the patient clearly had competently refused.

Consent also applies to people with mental health problems or learning disabilities: these individuals still have the right to refuse and consent to care. If someone is sectioned under the Mental Health Act, or if the Courts have appointed someone designated to make decisions on behalf of the individual, it is expected that people who know the patient would participate in the assessment and care/treatment planning to make certain that the person’s wishes are respected and that care decisions are made in the individual’s best interest.

With children, there are special considerations around competence to consent. Parents can give (or refuse) consent, but the age and ability of the child to understand are taken into consideration. If you are working with children, you need to be aware of the specific protocols and procedures around consent.

The truth is that, under law, no one (except, with certain limitations, a parent or a Court-appointed guardian) automatically has the right to make a decision on behalf of anyone else. You have to be sure as much as it is possible that whatever you do is what the patient would want.

Obtaining consent

It also means making sure the patient is aware of alternatives and options. This isn’t necessarily you speaking to the patient about those options, but it might mean you challenging someone else to make sure they have. As an example:

You are a theatre nurse. Mrs Turland is about to have her anaesthesia. As you are helping her, she asks you a question about the procedure. You know that the question should have been answered as part of giving consent.

Did you know that you have an obligation to stop and make sure her question is fully answered before she has the procedure? Will that get people all hot and bothered? Probably. Will people feel that this is an avoidable delay? Probably. Should you just assume that she forgot, so that the procedure starts on time and no one gets upset? No, absolutely not. Your duty is to protect the patient and no obligation is more important. No one, not the greatest and mightiest consultant, not an MP, not even the ruling monarch, is more important than your patient.

All individuals have the right to information about their health and what is happening to them. We are obliged to provide information that is honest, accurate and presented in a way that makes it as easy as possible for the patient to understand.

Sometimes, patients’ families might say ‘Don’t tell them’. It is true that some people might not want to know, or might want someone else to make decisions for them. If someone’s family says ‘Don’t tell my mother she has cancer, she wouldn’t want to know’ you should be sensitive to the patient’s wishes, but you need to know who has decided that the patient doesn’t want to know. It might be as simple as asking the patient ‘If there was something really wrong with your health, how much would you want us to tell you?’. If the patient says ‘Talk to my daughter about that …’ you have your answer. If the patient says ‘Tell me everything; I want to know it all …’ then this is a very difficult situation: you need to seek advice from your employer, from the NMC, from a solicitor or from your union/professional organisation.

Part of consenting is respecting when patients say ‘No’. As long as you are sure the patient understands the consequences, then that person has the right to say ‘No’, even if refusal shortens his or her life. Only a Court can force someone to have treatment. This is a legal right: it differs only when the health of an unborn child is at stake, when the team would need to look at the situation and make a decision about what to do.

Think about this: does an elderly person who won’t take his heart tablet have the right not to take it? Do you have the right to hide it in food to make him take it?

Documentation

The person who ‘gets’ a patient’s consent must document it. This can be by adding a document the patient has signed to the patient record, or writing something like ‘Explained intubation and ventilation procedure to patient. Explained possible risks and likely outcomes. Patient stated that the procedure should go ahead. Patient unable to sign document due to physical condition. Consent witnessed by nurse V Tremayne’.

If consent should have been documented but isn’t, you must make sure that someone actually did ensure that the patient gave consent. An example of this is when a patient hasn’t signed a consent form for surgery. You shouldn’t just say ‘Sign this’. You should ask the person responsible for the surgery to come and make sure the patient gives consent. You might not be able to determine that the patient truly is consenting because you might not understand the risks or have the information the patient needs to make an informed choice.

You should also document any refusal:

Attempted to give Mr Patterson an injection of insulin. Mr Patterson stated ‘I don’t want that any more’ and put his hands up in a ‘Stop’ position. I explained the importance of insulin and what could happen if he didn’t have the injection. Mr Patterson said ‘I don’t care if I go blind or my kidneys fail – I’m not having any more needles.’ Mr Patterson is oriented to person, place and time, and does not appear confused. No history of dementia or confusion. Referred to Diabetes Specialist Nurse for further assessment. Insulin not given. Doctor made aware.

In the above example, the nurse doesn’t just say ‘He said “No”, I said “OK” ’. The nurse shows that she is making sure the patient has the support and help he needs, by documenting that she referred him to the Diabetes Nurse. She is also documenting that the person was not confused; this shows that she did check to see if the patient was competent.

Act to identify and minimise risk to patients and clients

Everything you do – or fail to do – is your responsibility. You can’t blame anyone else – there is no get-out clause that you were ‘only following orders’. As a nurse, you have an obligation always to act in the best interest of the people for whom you care. This could mean telling a colleague or another professional that he or she is wrong. Again, your patients have to trust that everything you do is always in their best interest. It’s your duty to make sure your patients are safe and that their care is appropriate and delivered competently.

You must make sure that your practice, the care you deliver and the environment in which it is delivered are safe, therapeutic and ethical. If you believe a patient to be at risk, because you are concerned that for whatever reason another practitioner might not be fit to practise, you are obliged to speak up. If you are concerned about doing this, contact the NMC, your union/trade organisation or speak to your manager. All organisations have policies in place to guide your actions. Remember: the patient comes first.

When it comes to patients being at risk, you can’t afford to wait: if you are worried that a patient is at risk because of the environment and you can’t fix it yourself, you must report your concerns to someone senior. It must also be in writing. That’s where incident reports come from!

Because you are a nurse 24 hours a day, on or off duty, you have a duty to provide care even when you are not at work. You don’t have to be a paramedic – what you need to do is act reasonably to prevent the person from coming to further harm. If you are a mental health nurse and you arrive at the scene of a traffic accident, all that might be expected of you would be to move the injured person into the recovery position; if you were an experienced A&E nurse, a little more might be expected! The NMC says ‘The care provided would be judged against what could reasonably be expected from someone with your knowledge, skills and abilities when placed in those particular circumstances’. What you can’t do is walk past as if nothing happened. For example:

You are working on a very busy surgical ward. All the beds are full; the hospital is at full capacity. You find that one of the nurse call lights is broken; no matter what you do you can’t get it to work. There isn’t another bed to move the patient into. What do you do?

How many people have since reflected that they thought it was odd that Dr Shipman used so much morphine, and that so many more of his patients died at home in relation to similar-sized practices? People later said they had doubts. Why did no-one to speak out? What was it that kept them silent?

If someone had raised these concerns, there might be quite a few people around today living useful, happy lives. If you think something is not right, reflect on it. If you have nagging doubts, raise your concerns. I am sure that the people who didn’t speak up about their concerns over Dr Shipman have trouble sleeping at night, realising how much they could have done by speaking up. It’s not a lesson to learn in hindsight.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree