Principles of restricted mobility management

Pressure area care

Learning outcomes

Having read this chapter, the reader should be able to:

Restricted mobility can occur for a variety of reasons, e.g. during and following regional or general anaesthesia, postoperatively, increasing the risk of a pressure injury occurring. This risk increases further in the unwell woman. It is not just women who are at risk but babies, too. While the occurrence of pressure injuries within the maternity setting is low, they do occur and every patient is potentially at risk of developing a pressure ulcer if risk factors are present (Butcher 2004, McInnes et al 2011, NICE 2014). Thus it is important the midwife understands why they occur and how they can be prevented and, if they occur, contact the Tissue Viability Nurse for advice. Bennett et al (2004) caution that pressure ulcers could be indicative of clinical negligence with evidence that litigation could occur as it has in the US. Dimond (2003) agrees, suggesting that while patients and relatives have traditionally accepted that pressure ulcers were unavoidable, they are now being viewed as evidence that a reasonable standard of care and action has not been met as a reason to claim compensation. Pressure ulcers are often reportable as an incident and an investigation initiated to determine if there were any omissions in care. This chapter focuses on the principles of pressure area care including a discussion of the aetiology and classification of pressure ulcers. The factors that influence the development of pressure ulcers are given, followed by a discussion of the assessment of skin integrity.

Definition

A pressure ulcer is a skin ulceration that forms due to localized tissue necrosis, commonly found on the parts of the body that have received unrelieved pressure. It has previously been referred to as a ‘decubitus ulcer’, ‘pressure sore’ or (less commonly) a ‘bedsore’.

Common sites for pressure ulcer formation

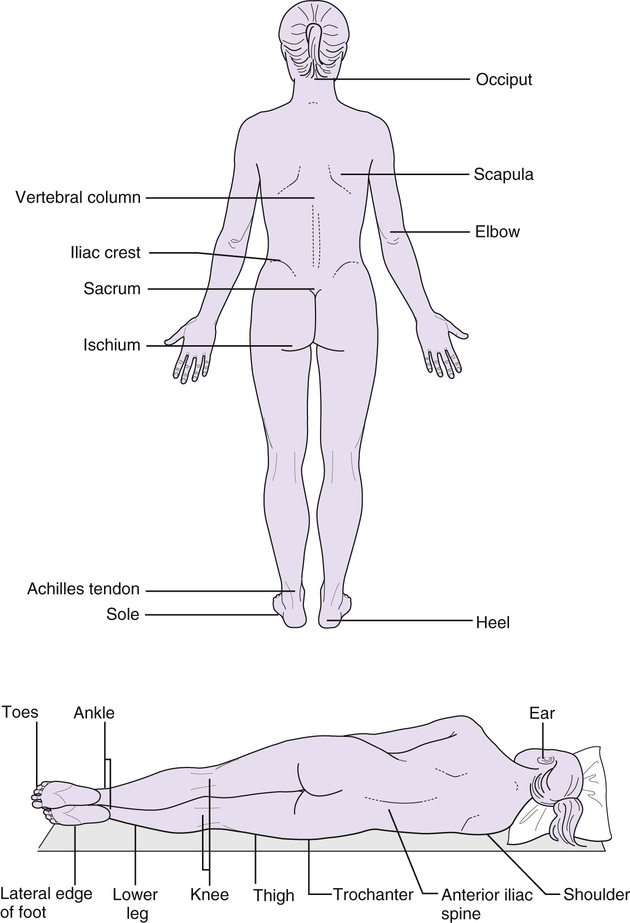

Although pressure ulcers can form on any part of the body, the commonest sites are the sacrum, buttocks, trochanter, and calcaneus (heels) (Bowen & Noble 2014, McGinnis & Stubbs 2014) with toes, knees, ischial tuberosities, shoulders, elbows and ears also having the potential to be affected (Fig. 53.1). Pressure may also occur from drainage tubes, indwelling catheters (against labia), nasogastric tubes (nasal passages), nasal oxygen cannulae and graduated compression stockings. Babies may also develop a pressure ulcer in the occipital region.

Effects of pressure

When sitting or lying, pressure is transferred from the external surface to the underlying bone via the different skin layers. This results in compression of the skin, subcutaneous fat, muscle and blood vessels. The pressure is directed downwards in an inverted cone shape and has a pressure gradient with the highest pressure at the apex. The pressure within these deep tissues is up to five times greater than within the epidermis (Dolan 2011). Consequently the pressure within the blood vessels increases. Normal capillary pressure is 12–32 mmHg; when the pressure exceeds this, the blood vessel becomes distorted and occludes (Colwell 2015). Blood flow is reduced and ischaemic injury can occur. Additionally the lymphatic supply can be occluded with accumulation of toxic substances that further increase cell damage (Hosking 2013). For the majority of people, once the pressure is removed reactive hyperaemia occurs as blood flow begins again and reperfuses the area. The area then becomes red and warm with the redness lasting up to 50–75% as long as the time the pressure prevented blood flow (deWit & O’Neill 2014). It can be difficult to detect hyperaemia in darkly pigmented skin. Bowen & Noble (2014) advise touching the skin to detect warmth. If the redness resolves or the area blanches under fingertip pressure, it is unlikely damage has occurred to the underlying tissues. However, a cycle of ischaemia and tissue reperfusion during periods of prolonged pressure is thought to contribute to tissue damage (Hosking 2013).

If the pressure is not relieved, the risk of ischaemic injury increases so that when the pressure is removed non-blanchable hyperaemia occurs. No blanching is seen with fingertip palpation – this is the first stage of skin injury and indicates deep tissue injury, although it may still be possible to reverse the damage at this stage (Colwell 2015). The cells rub together causing the cell membranes to rupture, releasing toxic intracellular material and normal skin colour is not restored. Damage can occur within 1–2 hours of continued pressure but generally is affected by the duration and amount of pressure, skin integrity, and ability of supporting structures to redistribute pressure (Bowen & Noble 2014, Colwell 2015). A deep pressure ulcer can arise when the lymphatic vessels and muscle fibres tear. In the healthy adult with full sensation, this will result in pain causing the individual to move (Benbow 2008). Where sensation is impaired (e.g. epidural anaesthesia) the change of position does not occur spontaneously.

Shearing can compound the effects of pressure. A shearing force is the pressure exerted against the skin in a direction parallel to the body’s surface, occurring when the body moves up or down the bed while in an upright position. As the layers of muscle and bone slide in the direction of the body movement, the skin and subcutaneous layers stick to the bed surface, causing the bone to slide down into the skin, with a force exerted onto the skin. This can happen if the woman is pulled up the bed rather than lifted. A shearing force results at the junction of the deep and superficial tissues. The microcirculation is compressed, stretched and damaged, causing microscopic haemorrhage and necrosis deep within the tissues. This is compounded by the decreased capillary blood flow resulting from the external pressure against the skin. Eventually, a channel opens through the skin and the necrotic area drains through this (tunnelling). The areas commonly affected by shearing forces are the sacrum and coccygeus.

The skin can also be damaged by friction but this is no longer considered a cause of pressure ulcers. Friction is the mechanical force exerted when the skin is dragged across a coarse surface (e.g. bedding). Antokal et al (2012) suggest friction may cause mechanical damage to the superficial tissue cells; thus damage is due to excessive deformation rather than ischaemia. The epidermis is rubbed away, giving the appearance of a shallow abrasion injury, often on the elbows and heels. The effects of friction are exacerbated by moisture (as for shearing) (Benbow 2008).

Deep tissue necrosis often occurs first at the bony interface as a result of this pressure, and the fact that muscle tissue is more sensitive and less resistant to pressure than the skin. Pressure exerted at the bony interface then emerges at a point in the surface of the skin. A small, inflamed area, over a bony prominence, may indicate tissue breakdown that is much deeper and wider than indicated at the surface of the skin.

Classification of pressure ulcers

Pressure ulcers are classified using the International National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel/European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP/EPUAP) pressure ulcer classification system (NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA 2014). This has four recognized stages related to the depth of tissue damage and involvement of associated structures. The stages can be referred to as a grade, stage or category.

• Grade 1: intact skin showing non-blanchable erythema – the early sign of potential ulcer formation. The skin may also be warm or cool, discoloured, show signs of oedema, induration, or hardness, or feel boggy. There may be pain or itching at the site. In darkly pigmented skins the area will be a persistent red/blue colour with purple hues (Bowen & Noble 2014) and the colour may differ from the surrounding tissue (Hosking 2013). This will heal slowly within 7–14 days without epithelial loss (Colwell 2015).

• Grade 2: partial-thickness skin loss of epidermis and/or dermis – a superficial ulcer that presents as a shiny or dry abrasion, blister (ruptured or intact) or shallow crater. There is a red-pink wound bed without slough (Hosking 2013). No bruising is noted (indicates deep tissue injury, Colwell 2015). Healing is through re-epithelialization.

There are two further stages that are ungraded:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree