CHAPTER 25 Principles of practice for supportive care: diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder that affects an estimated 250 million people worldwide. Data indicates that one million Australians (7.6% of the population) (Dunstan et al, 2002) have diabetes, although up to half the people with type 2 DM are undiagnosed, and therefore do not receive treatment. In addition, 6% of Australians have impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), which is a precursor to type 2 DM. The incidence of DM is increasing, and there is currently no cure (Dunstan et al, 2002).

There are two primary forms of DM. About 10–15% of people have type 1, and 85–90% have type 2 DM (Dixon & Webbie, 2006; Dunstan et al, 2002). There is a third form that is increasing in incidence. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is first diagnosed during pregnancy and is increasingly common in developed countries. GDM is also considered to be a precursor to type 2 DM, and up to half the women diagnosed with GDM develop type 2 DM over the 20 years following pregnancy (Lee et al, 2007). Regardless of the type, DM is characterised by chronic hyperglycaemia with disturbance of carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism resulting from defects in insulin secretion and insulin action independently or in combination. This chapter focuses on the management of type 1 and type 2 DM. Guidelines for the management of GDM can be found in midwifery text books and journal articles (Lee et al, 2007).

The incidence of type 2 DM is not distributed equally across the community, with some ethnic groups being over-represented. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are particularly at risk, with up to 50% of people in some communities having DM (Dunstan et al, 2002). The incidence of GDM is also increasing, and is estimated to occur in around 5% of pregnancies in Australia, although incidence rates as high as 20% are found among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and women from high-risk populations such as from the Indian sub-continent, Asia and Pacific Islands (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2002).

The goal of treatment is to assist the person with DM to achieve and maintain a blood glucose level (BGL) that is as close to physiological levels as possible, delaying onset and reducing the severity of diabetes-related complications, and decreasing the associated morbidity and mortality. A combination therapy of diet, medication and exercise, supported by education designed to meet the needs of each person, is the most effective way to achieve this goal. Two large landmark studies have demonstrated an association between poor control of blood glucose and the onset and progression of complications for type 1 (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group, 1993) and type 2 DM (Stratton et al, 2000), and have identified the optimal BGLs for both types of DM. These studies remain the benchmark because their cost and scale probably preclude replication.

DIAGNOSIS OF DIABETES

TYPE 1 DIABETES

Type 1 DM is the result of destruction of beta-cells in the pancreas. This destruction can occur for some time before clinical symptoms are obvious, although the progression of symptoms is rapid once the remaining beta-cells are unable to meet the body’s demand for insulin (American Diabetes Association, 2007; De Fronzo et al, 2004). Type 1 is the most common form of DM among children and young adults, although onset can occur at any age. The incidence of the disorder varies around the world. The highest incidence is reported in Scandinavian countries and the lowest in Oriental groups and populations living in the tropics. The disorder is also extremely rare among Native American tribes (Karvonen et al, 2000).

Type 1 DM has been associated with genetic determinants, environmental factors and acquired factors, including autoimmune reactions. Autoimmune reactions appear to play a significant role, as up to 70% of newly diagnosed people have islet cell antibodies (De Fronzo et al, 2004). Some researchers have identified a peak in diagnosis in the winter months, although that is not consistent across all countries. Nevertheless, the seasonal incidence of the disorder suggests that viral infection is one cause (De Fronzo et al, 2004). The term ‘idiopathic diabetes’ is used for forms of type 1 diabetes with no known aetiology (American Diabetes Association, 2007). Discovering a cure for type 1 DM is a priority for researchers investigating the disorder, but at this stage there is no cure and no preventive measures can be taken. It is important for nurses to be aware that, unlike type 2 DM, obesity and lack of exercise do not contribute to the development of type 1 diabetes.

TYPE 2 DIABETES

Type 2 is the most common form of DM and, in some groups, including the Native American tribes and populations in the South Pacific, it is the only form of diabetes (De Fronzo et al, 2004). People with Type 2 DM do not usually require insulin to survive, although many do use insulin to improve glycaemic control and their quality of life (American Diabetes Association, 2007).

Although the aetiology of type 2 DM is not clear, there is a strong familial tendency to develop the disorder, particularly when combined with lifestyle factors such as obesity. Women who have previously developed GDM have an increased risk of developing type 2 DM (Lee et al, 2007). Unlike type 1 DM, the beta-cells are not destroyed by autoimmune processes and DKA rarely occurs spontaneously, although it may occur in conjunction with stress or other illness, such as infection (American Diabetes Association, 2007). Individuals who are overweight or obese, do not exercise and eat a diet high in fat are particularly at risk of developing type 2 DM. People who are slightly overweight, but who may not be obese by traditional measures, are also at risk because abdominal obesity is strongly associated with insulin resistance. Abdominal fat is also associated with increased cardiovascular disease (Aguilar-Salinas et al, 2006). Increasing age is also a factor, therefore some lean elderly people will develop type 2 DM. Insulin resistance is a distinguishing feature of the disorder and some people may have normal or elevated insulin levels (Bonadonna et al, 2006).

Metabolic syndrome, which is strongly associated with insulin resistance, is the term for a cluster of symptoms and signs associated with type 2 DM and cardiovascular disease, namely abdominal obesity, dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance, hyperglycaemia, impaired fibrinolysis and hypertension (Rewers et al, 2004). The risk of developing diabetes or a cardiovascular event increases as the levels for these indicators increase above the normal range (Aguilar-Salinas et al, 2006; Bonadonna et al, 2006). DM is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, and people with DM and insulin resistance are at higher risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (Bonadonna et al, 2006).

There are two myths about type 2 DM that unfortunately continue to be perpetuated by some health professionals, despite the evidence that DM is the third most common cause of death in Australia. The first is that levels of blood glucose that are in the low range of elevated are not significant. You may hear individuals say that they have ‘… a touch of sugar, but nothing to worry about’. In fact, any elevation of blood glucose above the normal range places the person at risk of developing all of the chronic complications (discussed later in this chapter) associated with DM. The second myth is that type 2 DM can be cured. With effective management, including weight loss, increased exercise, dietary changes and medications, the blood glucose level may return to the normal range. However, the pathological processes associated with type 2 DM will manifest at any time if the individual does not continue to follow the recommended lifestyle practices.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

DM must be considered the cause when the fasting BGL is above 7.0 mmol/L, or random levels of 11.1 mmol/L or above (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2002). If there is doubt about the diagnosis, an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is usually performed. Following an overnight fast, an intravenous blood sample is collected and a 50 or 75 gram glucose drink is consumed. Blood samples are collected at one hour and two hours following the glucose drink. The BGL will remain elevated in the person with diabetes (World Health Organization, 1999).

TYPE 1 DIABETES

The signs and symptoms of type 1 DM develop rapidly (over days to weeks) and include hyperglycaemia, excessive thirst, frequent urination, excessive hunger, nausea and vomiting, weight loss and blurred vision (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2002). People with type 1 DM may be acutely ill when diagnosed, frequently presenting as a medical emergency with hyperglycaemia over 15 mmol/L, ketone bodies in the urine and signs of acidosis and severe dehydration. A detailed description of the signs, symptoms and management of severe hyperglycaemia is not provided here: you are advised to consult one of your texts if you need to revise that information. An OGTT is frequently not necessary to confirm the diagnosis as the random BGL will be above 11 mmol/L.

TYPE 2 DIABETES

The incidence of type 2 DM in children and adolescents is increasing in developed countries. Young people who develop mature onset diabetes commonly have a family history of type 2 DM and occasionally they present with DKA, although these young people do not have insulin cell antibodies as is the case with type 1 diabetes (Alberti et al, 2004).

INTERVENTIONS

This section provides an overview of management. DM is a complex disorder that is associated with other disease processes, for example cardiac disease and stroke, and leads to complications in almost all body systems. Therefore you are advised to consult specialised resources to assist you to develop appropriate care plans for people with DM.

MEDICATION MANAGEMENT

Type 1 diabetes

The most common regimens for people with type 1 DM are either:

Insulin is administered by subcutaneous injection using either a needle and syringe, an insulin pen device or, more recently, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) by an infusion pump worn by the person (Lenhard & Reeves, 2001). Current forms of insulin must be injected, as they are rendered inert by digestion. However, new forms of oral (Diabetes Prevention Trial—Type 1 Study Group, 2005) and inhaled (McElduff & Yue, 2007; Rosenstock et al, 2004; Skyler et al, 2004) insulin are being tested.

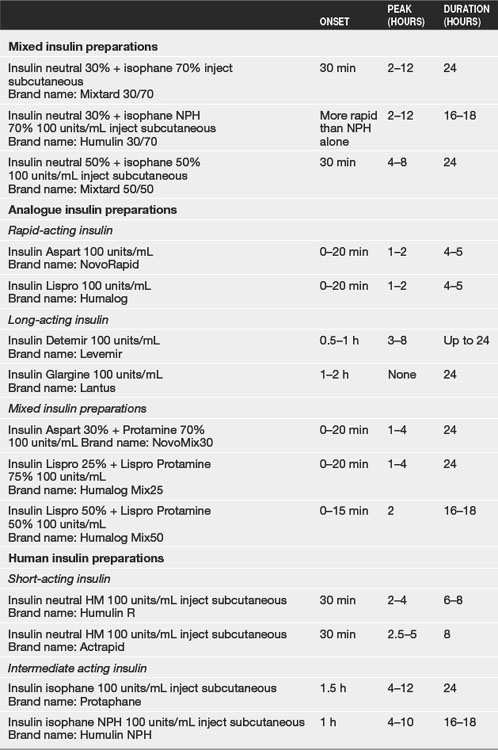

Insulin was originally extracted from the pancreas of cattle or pigs. Current forms of insulin are produced in a laboratory, which overcomes the problem of side-effects associated with insulin from animal sources. The name and time of onset, peak and duration of action of insulin available in Australia are presented in Table 25.1 (Mims Point of Care Data Base, 2007).

Insulin doses are individualised depending on the person’s response. It is important to note that insulin requirements in all patients are dynamic and therefore require frequent monitoring and dose adjustment are required to achieve the best possible glycaemic control. Early in the diagnosis of type 1 DM there is often a phase when there is some residue insulin secretion, and insulin replacement therapy may not be required for a brief period of time. This phenomenon is commonly referred to as the ‘honeymoon’ period (Harmel & Mathur, 2004) and is a result of the beta-cells in the pancreas rallying to produce the last of the person’s insulin prior to their complete destruction. This phenomenon can prove challenging for patients and their families as the diabetes goes into remission. Support and education are the key to successfully negotiating this period in the disease process.

Background or long-acting insulin

Long-acting insulin is used specifically to control the release of stored glucose from the liver, and therefore control the fasting BGL. Recent developments have enabled the design of new insulin analogues which have long-acting profiles that are more useful in the management of DM, particularly for people with type 1. Insulin Glargine (Lantus) (Ratner et al, 2000) and Insulin Detemir (Levemir) (Hermansen et al, 2001) are commonly used as once-daily or twice-daily injections respectively as background insulin therapy. These insulin analogues have largely replaced the more traditional therapies of Isophane (Protaphane, Humulin NPH) (intermediate-acting insulin) and Lente (Ultralente, Humulin L) and Ultratard (long-acting insulin). Glargine and Detemir provide a prolonged and reasonably consistent level of insulin that more accurately mimics insulin secretion in people without DM (Ratner et al, 2000), unlike the traditional types of longer acting insulin. The onset of action of intermediate-acting insulin is around 90 minutes after injection, with the peak action at 4 to 12 hours and duration of 24 hours. The onset of action for long-acting insulin is around 4 hours, followed by a broad peak of action that lasts for 8 to 16 hours with a duration ranging from 20 to 36 hours.

Rapid-acting insulin

The preferred option for mealtime insulin in adults is one of the rapid-acting analogues either Insulin Aspart (NovoRapid) or Insulin Lispro (Humalog). Both have rapid onset of action (10–20 minutes) and short duration (3–5 hours), thus mimicking natural secretion of insulin following meals. Rapid-acting insulin is administered before meals and large snacks of more than 15 grams of carbohydrate (equivalent to one slice of sandwich-thickness bread). It is ideal for adults with type 1 DM to have flexible insulin doses depending on their carbohydrate intake. Therefore it is important that management regimens for people with type 1 DM allow for a flexible lifestyle and that they have the opportunity to attend specific educational programs to provide them with the skills and knowledge required to assume a self-care role. Education programs such as DAFNE (Dose Adjustment for Normal Eating) (McIntyre, 2006) have been designed specifically for people with type 1 DM. A detailed description of the characteristics of various types of insulin can be found in pharmacology sources of evidence.

Continuous subcutaneous infusion of insulin (CSII)

The advent of portable and reliable subcutaneous infusion pumps has revolutionised the management of type 1 DM (Boland et al, 1999; Fox et al, 2005). Insulin pumps reduce the need for multiple daily injections and allow for better glucose control, as the therapy is adjusted frequently. One drawback of using CSII is that equipment failure, including blockage or disconnection of the tube, can result in a rapid elevation of BGL. The pumps and the necessary consumables are expensive and not always covered by private health insurance, although consumables are available through the government-subsidised National Diabetes Support Scheme. Cost does prevent some people using pump therapy. Successful use of a pump is dependent upon frequent testing of BGL using the Self-Blood Glucose Monitoring (SBGM) technique and the person’s ability to accurately count carbohydrate intake.

TYPE 2 DIABETES

Unlike people with type 1 DM, people with type 2 DM do not require exogenous insulin to sustain life. Dietary modification with increased exercise is the first approach to management of people with type 2 DM, particularly those who are overweight and with a BGL just above the normal range. Nevertheless, over the past decade the medication management of type 2 has changed significantly. Insulin is now commonly used when hyperglycaemia persists and the person is taking maximum doses of oral medications and new categories of oral medication have been introduced (Kamp, 2007).

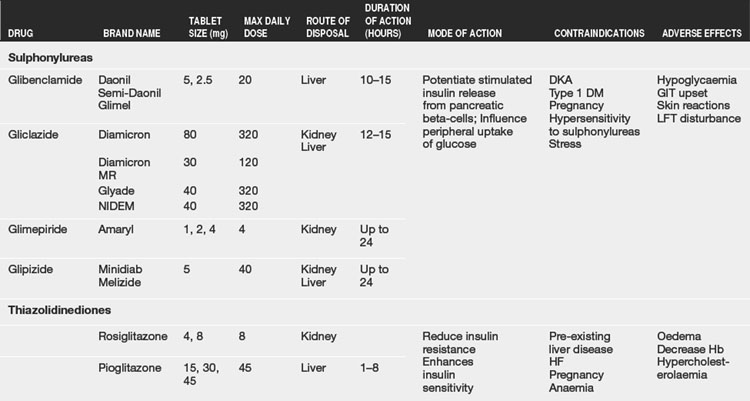

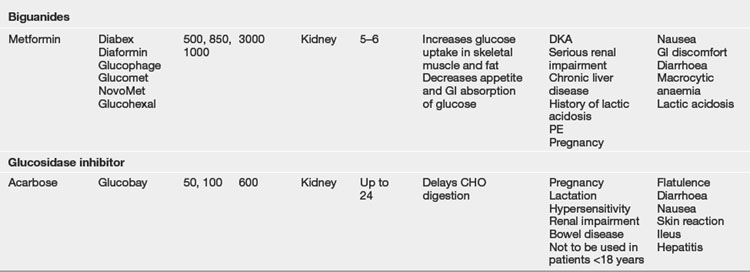

Insulin sensitising drugs

These medications lower BGL by sensitising the muscle and liver cells to insulin, which may improve the insulin resistance present in type 2 DM and increasing the uptake of glucose by cells (Kamp, 2007). Insulin sensitising drugs have the advantage of lowering BGL without placing the person at risk of hypoglycaemia and are effective for people who are overweight or obese. Commonly used medications are Biguanide (Metformin) or a Thiazolidinedione. Recent research (Bonadonna et al, 2006) has demonstrated that the use of Metformin can significantly reduce the incidence of both micro-vascular and macro-vascular complications, although it can also cause gastrointestinal upset such as nausea, abdominal pain and diarrhoea. These medications are not suitable for all people and they should be introduced with caution due to their side-effects (see Table 25.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree