50. Principles of moving and handling

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Anatomy of the spine342

Principles of lifting343

Employers’ responsibilities347

Employees’ responsibility347

Role and responsibilities of the midwife347

Summary347

Self-assessment exercises347

References348

LEARNING OUTCOMES

Having read this chapter the reader should be able to:

• discuss the responsibilities of both the employer and employee in reducing the risk of injury occurring when moving or handling

• describe the anatomy of the spine and related structures, relating this to the mechanics of moving and handling

• discuss how lifting should occur, should it be required

• describe how a good posture can be achieved.

Manual handling accidents have far-reaching implications, not only for the midwife who is unable to work in both the short and sometimes the long term and who may suffer pain and disability, but also for employers, in terms of time lost from work and large financial compensation packages paid out to employees (Barnes, 2007, Cowell, 1998, RCN (Royal College of Nursing), 2004, Rinds, 2007a, Smedley et al., 2005, Stevens, 2004 and White, 1998). In 1998 a nursery nurse was awarded £78 000 in compensation following a lifting injury that resulted in severe damage to her back and an inability to work for 4 years (Tolley 2000). In 2004 the Royal College of Nursing obtained £4 million compensation for members who were injured at work (Nursing Standard 2007). Staff requiring time off from work to recover from a back injury and who experience a recurrence are likely to require longer periods of time off to recover than they needed initially (Wasiak et al 2006).

Injuries can occur through the use of incorrect lifting techniques, inappropriate lifting and moving as well as adopting poor posture for procedures such as delivery and assisting with breastfeeding. This chapter focuses on the principles of moving and handling, considering how the risk of injury can be minimised, and employers’ and employees’ responsibility in relation to this. Relevant anatomy of the spine is discussed and related to both lifting and posture, and how injury can occur. There is a vast amount of literature and legislation relating to manual handling which is added to regularly; hence it is not possible to cover this in detail. This chapter provides an overview of manual handling and the reader is advised to read other texts and visit the Health and Safety Executive website (www.hse.gov.uk) for further information.

Back injuries appear to be more common in newly qualified and very senior staff. Blue (1996) suggests this may be due to acute trauma in newly qualified staff, but could be a result of the cumulative effect of smaller traumatic episodes, combined with reduced physical fitness, for older, more senior staff. Both employers and employees have a responsibility to make every effort to reduce the risk of injury occurring. For employees this could include maintaining their own fitness levels; Blue (1996) suggests back injuries occur less frequently in people who are physically fit and undertake high-energy activities on a regular basis such as swimming and running.

Anatomy of the spine

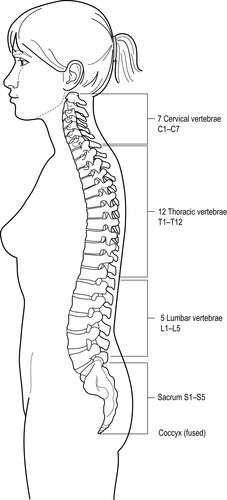

The spine, or vertebral column, is responsible for maintaining the upright posture of the body, provides flexibility of movement and protects the spinal cord. The spine consists of 33 separate bones or vertebrae: 24 moveable and 9 fused vertebrae (Fig. 50.1):

• seven cervical vertebrae: C1–C7 (the neck)

• twelve thoracic vertebrae: T1–T12 (the upper trunk)

• five lumbar vertebrae: L1–L5 (the lower trunk)

• five fused sacral vertebrae: S1–S5 (the sacrum)

• four fused coccygeal vertebrae (the coccyx).

|

| Figure 50.1 • Vertebral column-bones and curves (Adapted with kind permission from Wilson & Waugh 1996) |

The vertebrae articulate with their immediate neighbours, with muscles attached, and the thoracic vertebrae meet with the ribs. The coccyx articulates with the sacrum at the sacrococcygeal joint. Each vertebra has a main body, situated anteriorly, that acts as a shock absorber as the posture changes. The size of the vertebral body varies throughout the vertebral column, beginning small with the cervical vertebrae, increasing in size to the lumbar vertebrae. Behind the body is the vertebral foramen, a large central cavity that contains the spinal cord, with nerves and blood vessels passing out through spaces between the vertebrae.

A flexible intervertebral disc connects the vertebral bodies to each other. These discs, which have a fibrocartilage outer layer surrounding an inner semi-solid centre, assist with absorbing shock from movement and affect the flexibility of the spine. The vertebrae and discs are supported by ligaments that help to maintain the vertebrae in position and limit the amount of stress transmitted to the spine by restricting excessive movement. The ligaments do not produce as much support for the lumbar vertebrae, creating an inherent weakness in this area. The lumbar vertebrae experience higher levels of stress when the back is bent and the knees kept straight while lifting than when keeping the back straight and the knees bent (Kroemer & Grandjean 1997). This stress increases significantly if the back is twisted, as can occur when leaning over a bed.

The vertebral column is not straight, but has four curves (see Fig. 50.1):

• cervical curve (convex curve anteriorly)

• thoracic curve (concave curve anteriorly)

• lumbar curve (convex curve anteriorly)

• sacral curve (concave curve anteriorly).

The first three curves are important in relation to posture; when they meet in a midline centre of balance, weight distribution is balanced and a healthy posture ensues, protecting the supporting structures from injury (Blue 1996).

Considerations for moving and lifting

There are four important categories that should be considered in relation to moving and lifting, as these can affect the likelihood of an injury occurring (HSE 1992):

1. the task

2. the load

3. the working environment

4. the individual.

The task

Does the task involve:

• holding an object or load away from the trunk?

• twisting or stooping?

• reaching upwards?

• using large vertical movements?

• carrying an object for a long distance?

• strenuous pushing or pulling?

• repetitive handling?

• insufficient rest or recovery?

• unpredictable movement of an object, e.g. carrying fluids?

The load

Is the load or object:

• heavy?

• bulky?

• difficult to hold?

• unstable, e.g. fluid?

• intrinsically harmful, e.g. sharp?

The working environment

Within the environment, are there:

• constraints on posture?

• poor or slippery floors?

• variations in levels?

• poor lighting conditions?

The individual

Does the job:

• require an unusual capability, e.g. in relation to weight of load?

• cause a hazard to anyone with a health problem?

• cause a hazard to anyone who is pregnant, or who has had a baby within the past 2 years?

• require special information or training?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access