Principles of manual handling

Learning outcomes

Having read this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• identify situations that place the midwife at increased risk from a moving and handling injury

• discuss the different factors that should be considered before undertaking a manual handling task

• discuss how lifting should occur, should it be required

• adopt a good posture with good understanding of why it is important

Manual handling refers to the moving of items/people either by lifting, lowering, carrying, pushing or pulling. While the weight of an object handled can be a cause of injury, the frequency with which the movement is repeated, the distance which an item is carried or moved, and the height at which an object is picked up/put down from are also sources of injury. Manual handling injuries occur not only through incorrect lifting techniques and inappropriate moving and lifting, but also through poor posture, prolonged standing, twisting, bending and stretching (Kay & Glass 2011). Injury may also occur when undertaking visual display unit (VDU) computer keyboard work, writing, pushing wheelchairs, pulling beds, as well as procedures such as delivery and assisting with breastfeeding, all of which can involve adopting an awkward posture, and lifting laundry bags and food trays (Carta et al 2010).

This chapter provides an overview of manual handling, focusing on the principles of moving and handling, considering how the risk of injury can be minimized, and employers’ and employees’ responsibilities in relation to this. Relevant anatomy of the spine is discussed and related to both lifting and posture, and how injury can occur. It is acknowledged that there is a vast amount of literature and legislation relating to manual handling which is added to regularly, hence it is not possible to cover this in detail. The reader is advised to read other texts and visit the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) website (www.hse.gov.uk) for further information.

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are the most common occupational disease in the European Union accounting for 42–58% of all work-related illnesses with a high occurrence among hospital workers (Magnavita et al 2011). Health and social care had the highest number of reported handling injuries in 2013–2014 in the UK with an incidence rate of 190 : 100 000 employees (HSE 2014). Anderson et al (2014) suggest injuries arising through moving and handling incidents are the most common cause of staff absence for >3 days in the health and social care setting. There are far-reaching implications of MSD, not just in terms of the pain and disability experienced by the injured worker, but also financial for the midwife who is unable to work in the short term and sometimes the long term, and also for employers in terms of staff absenteeism and presenteeism (reduced on-the-job productivity as a result of health problems, Letvak et al 2012) and large compensation packages paid to their injured employees (Barnes 2007, RCN 2004, Rinds 2007a, Stevens 2004). In 2004 the Royal College of Nursing obtained £4 million compensation for members who were injured at work (Nursing Standard News 2007). Staff requiring time off from work to recover from a back injury and who experience a recurrence are likely to require longer periods of time off to recover than they needed initially (Wasiak et al 2006).

Back injuries appear to be more common in newly qualified and very senior staff. Blue (1996) suggests this may be due to acute trauma in newly qualified staff, but could be a result of the cumulative effect of smaller traumatic episodes, combined with reduced physical fitness, for older, more senior staff. Cheung (2010) found MSDs were common among student nurses, which may also contribute to the incidence of MSDs in newly qualified staff. Both employers and employees have a responsibility to make every effort to reduce the risk of injury occurring. For employers it could include early manual handling training for all new staff and ensuring they are familiar with the devices available in their clinical area. For employees this could include maintaining their own fitness levels; Blue (1996) suggests back injuries occur less frequently in people who are physically fit and undertake high-energy activities on a regular basis such as swimming and running.

Anatomy of the spine

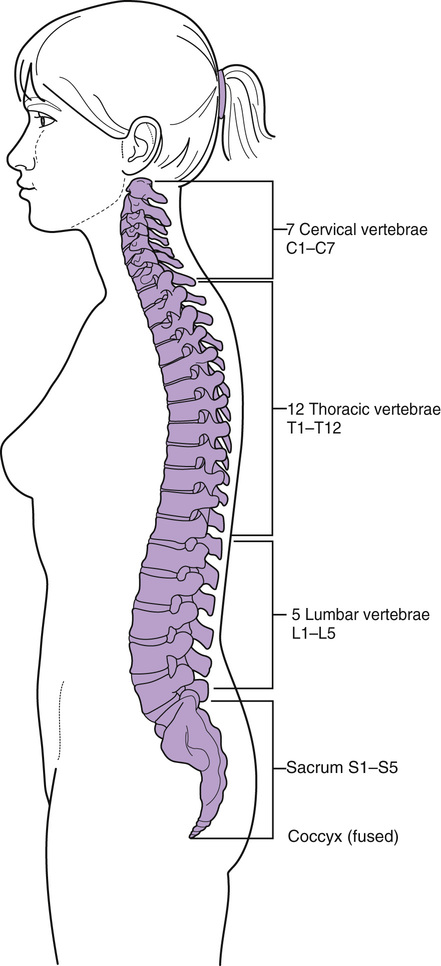

The spine, or vertebral column, is responsible for maintaining the upright posture of the body, provides flexibility of movement and protects the spinal cord. The spine consists of 33 separate bones or vertebrae: 24 moveable and 9 fused vertebrae (Fig. 50.1):

• seven cervical vertebrae: C1–C7 (the neck)

• twelve thoracic vertebrae: T1–T12 (the upper trunk)

• five lumbar vertebrae: L1–L5 (the lower trunk)

• five fused sacral vertebrae: S1–S5 (the sacrum)

The vertebrae articulate with their immediate neighbours, with muscles attached, and the thoracic vertebrae meet with the ribs. The coccyx articulates with the sacrum at the sacrococcygeal joint. Each vertebra has a main body, situated anteriorly, that acts as a shock absorber as the posture changes. The size of the vertebral body varies throughout the vertebral column, beginning small with the cervical vertebrae, increasing in size to the lumbar vertebrae. Behind the body is the vertebral foramen, a large central cavity that contains the spinal cord, with nerves and blood vessels passing out through spaces between the vertebrae.

A flexible intervertebral disc connects the vertebral bodies to each other. These discs, which have a fibrocartilage outer layer surrounding an inner semi-solid centre, assist with absorbing shock from movement and affect the flexibility of the spine. The vertebrae and discs are supported by ligaments that help to maintain the vertebrae in position and limit the amount of stress transmitted to the spine by restricting excessive movement. The ligaments do not produce as much support for the lumbar vertebrae, creating an inherent weakness in this area. The lumbar vertebrae experience higher levels of stress when the back is bent and the knees kept straight while lifting than when keeping the back straight and the knees bent (Kroemer & Grandjean 1997). This stress increases significantly if the back is twisted, as can occur when leaning over a bed.

The vertebral column is not straight, but has four curves (see Fig. 50.1):

• cervical curve (convex curve anteriorly)

• thoracic curve (concave curve anteriorly)

• lumbar curve (convex curve anteriorly)

The first three curves are important in relation to posture; when they meet in the midline centre of balance, weight distribution is balanced and a healthy posture ensues, protecting the supporting structures from injury (Blue 1996).

Considerations for moving and lifting

The HSE (2004) suggest there are four important categories to consider in relation to moving and lifting; these can affect the likelihood of an injury occurring:

These four areas can be made into an acronym to assist with recall, e.g. TILE (task, individual, load, environment) (Anderson et al 2014), LITE.

The task

Does the task involve:

• holding an object or load away from the trunk?

• using large vertical movements?

• carrying an object for a long distance?

• strenuous pushing or pulling?

• insufficient rest or recovery?

• unpredictable movement of an object, e.g. carrying fluids?

Stress on the lower back increases as the load is moved away from the trunk; e.g. if a load is held at arm’s length, the stress can be approximately five times higher than if it were close to the trunk (HSE 2004). Reaching up and using large vertical movements places extra stress on the arms and back with a load that is more difficult to control, as is an object with unpredictable movement, e.g. baby bath filled with water. The further the distance for which the load is held, the more it is that the grip on the load will need to be changed, which increases the risk of injury occurring. The HSE (2004) state carrying a load further than 10 metres will place more demand on the body than lifting and lowering. With repetitive movements, insufficient rest, and strenuous pushing or pulling, muscle fatigue can occur which increases the likelihood of an injury. The back, neck, and shoulders can be injured with pushing and pulling, e.g. a bed, wheelchair, with the risk increasing if the surface of the floor is poorly maintained. The HSE (2004) advise that when pushing or pulling a load, hands should be kept above the waist and below the shoulders demonstrating the importance of having the bed at the correct height when being manoeuvred around.

The load

Is the load or object:

If the load is deemed heavy, consideration should be given to using lifting equipment or having someone to assist with the task. A load that measures >75 cm carries an increased risk of injury as it can be difficult to maintain a suitable grip and can obscure the view in front of and beneath the person carrying it.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree