Principles of intrapartum skills

Perineal repair

Learning outcomes

Having read this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• state the aims of perineal repair

• describe the four degrees of perineal trauma

• discuss the role and responsibilities of the midwife when undertaking perineal repair

• discuss the current evidence for the choice of materials and techniques used

• describe how to infiltrate the perineum

• demonstrate tying a knot, continuous non-locked and subcuticular sutures

• list the factors that should be included with record keeping.

Approximately 85% of women who have a vaginal delivery in the UK experience some degree of perineal trauma and 60–70%, around 1000 women per day, will require suturing (Kettle et al 2012). Steen & Roberts (2011) suggest a second-degree tear is the most common spontaneous perineal injury during childbirth. Recognizing the degree of trauma and having the skills to undertake the repair is an important skill for the midwife. Perineal trauma and repair is associated with both short- and long-term problems (Beckman & Stock 2013). This chapter reviews the anatomy of the pelvic floor, the damage that may occur, the significance of correct repair, the evidence around perineal suturing, and the materials and techniques used. While care of the perineum postnatally is an important aspect of postnatal care, it is not covered within this chapter.

The pelvic floor

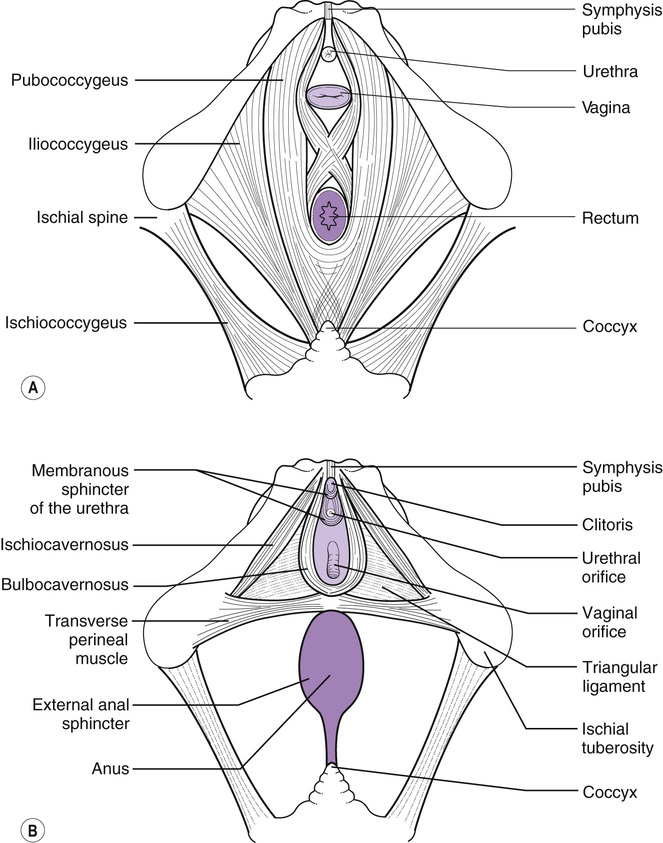

Within the pelvis are two layers of muscles in a hammock-shaped arrangement that provide support to the pelvic organs and prevents them from prolapsing and through which the urethra, vagina, and anal canal pass (Fig. 34.1). The pelvic floor is an important component in the correct functioning of the vagina, bladder, uterus and rectum; a damaged or weakened pelvic floor may cause long-term urinary, faecal and sexual morbidity. The deep muscles provide strength to the pelvic floor and are made up of three muscles – the pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus and ischiococcygeus – collectively referred to as the levator ani muscles. The superficial muscles consist of the ischiocavernosus, bulbocavernosus and transverse perineal muscles. The perineal body is a triangular-shaped structure situated between the vagina and rectum, with its apex pointing upwards. It is composed of two superficial muscles (bulbocavernosus and transverse perineal) and one deep muscle (pubococcygeus). As the presenting part descends during the second stage, it flattens and displaces but can be damaged spontaneously during the birth of the baby or via an episiotomy.

Aims of perineal repair

The aim or repairing the perineum is to realign the tissues into their correct anatomical position, promote healing by primary intention, and prevent haemorrhage by sealing off bleeding vessels and reducing the dead space into which bleeding can occur, causing a haematoma. Ultimately the aim is to restore the integrity of the woman’s pelvic floor and maintain normal function.

Perineal damage

The degree of perineal trauma is classified according to which structures are involved and do not include any reference to the depth or size of the injury. The accepted definitions are:

• first-degree: only the perineal skin is torn

• third-degree: this affects the same structures as a second-degree but also involves the anal sphincter and is classified further as:

■ 3a <50% of external anal sphincter torn

■ 3b >50% of external anal sphincter torn

■ 3c injury to both the external and internal anal sphincter

• fourth-degree: involving the structures with a third-degree tear and the anal sphincter complex and epithelium (NICE 2014, RCOG 2015).

Further damage may also occur to the walls of the vagina and labia while keeping the skin intact. Careful examination of the labia is required to determine if the clitoris or urethra have been damaged. Labial tears are usually described as ‘grazes’ or ‘tears’ but there is currently no accepted definition of what a labial tear or a graze is and thus this description is subjective. Jenkins (2011) suggests that labial tears are more likely to be sutured than grazes but cautions there is no evidence to support how labial trauma should be sutured.

The genital tract should be independently examined by two midwives as soon as possible post-delivery to assess the extent of perineal (and other) trauma (see p. 255) and decide whether it requires repair, by whom, in which environment and using which materials. Kettle et al (2012) emphasize the importance of skilled operators undertaking perineal repair by using the best techniques and suture materials that will result in the least amount of short- and long-term morbidity for the woman. Extensive trauma, such as third- and fourth-degree tears, require suturing by a senior obstetrician, often in theatre under general or regional anaesthesia. Suturing by a genitourinary specialist may be indicated if the urethra has been damaged.

To prevent the labia fusing, bilateral labial grazes that would be in apposition when standing or sitting should also be sutured. Arkin & Chern-Hughes (2001) cite a case study in which the labia needed surgically parting some months following abrasions in childbirth. If the woman declines suturing of bilateral labial tears, she should be advised about the risks and encouraged to part her labia daily to reduce the likelihood of fusion.

Suturing is the most common method of perineal repair; however, there is increasing interest in the use of tissue adhesive. Adhesive is currently used widely in other areas, e.g. paediatric and ophthalmic surgery, and initially it was thought the perineum would be an unsuitable site for adhesive use due to the amount of moisture in the area. Mota et al (2009) found the use of adhesive for skin closure shortened the time taken to close the skin layer and a similar rate of complications and pain compared with subcuticular suturing. Ismail et al (2013) are undertaking a review to evaluate the different methods of perineal repair and the reader is advised to review the results when published.

To suture or not to suture?

NICE (2014) recommend that first-degree tears where the wound is not in apposition and all second-degree tears should be sutured (although if following suturing of the muscles the skin is opposed, it does not need to be sutured). However, Elharmeel et al (2011) suggest that small tears can heal well without being sutured and short-term outcomes are similar to sutured tears; long-term outcomes were not evaluated in the studies they reviewed and the sample sizes were small. They conclude there is insufficient evidence to recommend whether suturing or non-suturing is best practice and propose women should be offered information and informed choice around perineal suturing until conclusive studies are available. The Royal College of Midwives (RCM) (2008) suggest there appears to be neither benefit nor disadvantage in relation to suturing or not suturing the skin. Viswanathan et al (2005) advise it is preferable to leave both the superficial vaginal and perineal skin unsutured.

When discussing with the woman whether or not to suture, the midwife should discuss the rationale for suturing, with the advantages and disadvantages, to allow the woman to make a more informed choice. The advantages of suturing include quicker initial healing of the tissues with better wound alignment compared with not suturing (Langley et al 2006, Leeman et al 2007) and reduced urinary problems (Metcalfe et al 2006). However, suturing can be a painful procedure in itself, may require the use of lithotomy, which can be difficult for some women (e.g. those with pelvic girdle pain) and may result in increased use of analgesia (Langley et al 2006, Leeman et al 2007). Metcalfe et al (2006) found reported levels of perineal pain were similar between sutured and unsutured women.

Choice of suture material

Both non-dissolvable and dissolvable sutures have been used over the years to repair perineal trauma with the latter being more popular in recent years. Kettle et al (2010) suggest the ideal suture material should be one that causes minimal tissue reaction, be able to hold the tissues in apposition during the healing process and be absorbed once healing has occurred. While the sutures remain in the tissues, the body views them as foreign material which may cause a significant inflammatory response. If microorganisms colonize the implanted sutures or knots it can be difficult to eradicate any resulting infection which may predispose to abscess formation and wound dehiscence (Kettle et al 2010).

Catgut, made from purified collagen derived from the small intestine of cattle or sheep or from beef tendon, retains full tensile strength for 10 days. It causes an inflammatory response within the tissues causing the suture to be broken down by proteolytic enzymes and phagocytosis, although absorption times can be unpredictable, particularly in the presence of a wound infection of malnutrition (Kettle et al 2010). Subsequently, both chromic catgut (treated with chromate salts to prevent the catgut absorbing so much water, which slows down the absorption process and reduces the inflammatory reaction) and softgut (catgut impregnated with glycerol to make it remain more supple and prevent excessive drying) were introduced (Kettle et al 2010). Catgut is no longer available to the UK market, having been replaced with synthetic sutures, but is still used in non-European countries (Kettle et al 2010). Additionally, because low-cost chromic catgut is more readily available, it is likely to be continued as the preferred suture material for perineal repair in most poorly resourced settings (Peveen & Shabbir 2009).

Synthetic sutures include polyglycolic acid (e.g. Dexon), Polyglactin 910 (e.g. Vicryl) and Vicryl Rapide) and Biosyn. The polyglycolic acid suture is made of 100% glycolide and is converted into a braided suture material which is similar to Vicryl. Kettle et al (2010) advise it is designed to maintain wound support for up to 30 days and be completely absorbed by 120 days. Polyglactin 910 is a copolymer of glycolide (90%) and lactide (10%) which is derived from glycolic and lactic acids. They are also braided and coated with a copolymer of lactide, glycolide, and calcium stearate to reduce bacterial adherence and tissue drag (Kettle et al 2010). They are absorbed more quickly, by 90 days. Vicryl Rapide has the same chemical composition as Polyglactin 910 but is irradiated during the sterilization process creating a faster absorption rate of 42 days while providing wound support for 14 days (Kettle et al 2010). Biosyn is a newer monofilament product composed of glycolide (60%), dioxanone (14%) and trimethylene carbonate (26%). It provides wound support for up to 21 days and is fully absorbed between 90 and 110 days (Kettle et al 2010) although Medtronic suggest their product is fully absorbed by 56 days (Medtronic 2008). This suture has less tissue drag and less tissue reactivity and promotes better wound healing (Medtronic 2008, Kettle et al 2010).

So which is the best type of suture to use for perineal repair? Kettle et al (2010) suggest catgut increases short-term pain and wound dehiscence with an increased need to resuture compared to synthetic sutures but also advise that there is an increased need to remove synthetic sutures. For synthetic sutures, Kettle et al (2010) suggest there is little difference between Polyglactin 910 and Vicryl Rapide. Fewer sutures required removing in the first 3 months with Vicryl Rapide use but there was a slightly increased risk of superficial partial skin dehiscence causing the skin edges to gape (much less than with catgut) (Kettle et al 2010).

Wound dehiscence is associated with infection and provides a potential route for systemic infection with increased risk for septic shock. Infection causes the edges of the wound to become softened which can lead to the suture cutting out of the tissue and causing the wound to breakdown (Kettle et al 2010). Harper (2011) cites the case of a maternal death from sepsis following a second-degree tear which became infected.

Overall the fast-absorbing polyglactin sutures are currently considered to be the suture material of choice as they are associated with less perineal pain, a reduced need for analgesia, less uterine cramping at 24–48 hours and at 6–8 weeks, a significant reduction in the need for suture removal, fewer healing problems in the short term, and earlier resumption of sexual activity (Greenberg et al 2004, Leroux & Bujold 2006, Viswanathan et al 2005). Size 2/0 is indicated for perineal tissue.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree