33. Principles of intrapartum skills

examination of the placenta

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Disposing of the placenta238

Role and responsibilities of the midwife239

Summary239

Self-assessment exercises239

References239

LEARNING OUTCOMES

Having read this chapter the reader should be able to:

• describe the structure and appearance of the placenta at term

• describe how the placenta is examined

• discuss the significance of the information obtained from the examination

• discuss the role and responsibilities of the midwife in relation to examining the placenta.

Examination of the placenta following delivery is an important skill undertaken by the midwife to reduce the occurrence of both postpartum haemorrhage and infection. This chapter describes the structure and appearance of the placenta, discussing the significance of deviations, and concluding with the procedure for undertaking examination of the placenta. It concludes with a brief discussion concerning disposal of the placenta.

Structure and appearance

The placenta is a disc-shaped structure that has both maternal and fetal surfaces. At term, the placenta weighs approximately 500–600 g (about one-sixth of the baby’s weight), has a diameter of 15–20 cm and is 2–3 cm thick. Early cord clamping may result in the placenta being proportionally heavier, whereas delayed cord clamping can produce a placenta that is proportionally lighter, due to the amount of blood transfused from the placenta to the baby at delivery. A larger placenta may be associated with maternal diabetes and multiple pregnancy, a smaller placenta with chronic intrauterine growth restriction.

Occasionally the placenta may develop with an abnormal structure and appearance such as a circumvallate placenta. The placenta enlarges beneath the endometrial surface and the embryonic sac enlarges above it; the endometrium between the two is compressed and obliterated resulting in an acellular membrane, which may affect the attachment of the placenta to the decidua, increasing the risk of placental abruption. The placenta has a thick, grey/white raised ring around the central part of the fetal surface, caused by the fetal membranes folding back on themselves.

Fetal surface of the placenta

The fetal side has a white shiny appearance due to the chorionic plate (a thin membrane continuous with the chorion) and the amnion that cover the surface. The fetal side is composed of 50–60 lobes or cotyledons, which are further divided into 1–5 lobules. Occasionally, the placenta may be divided into two (bipartite) or three (tripartite) separate, distinct lobes, each with an umbilical cord inserted into it. The cord presents as one cord until it is near the placental surface when it divides into two or three to supply each lobe (Fig. 33.1).

|

| Figure 33.1 • Bipartite placenta |

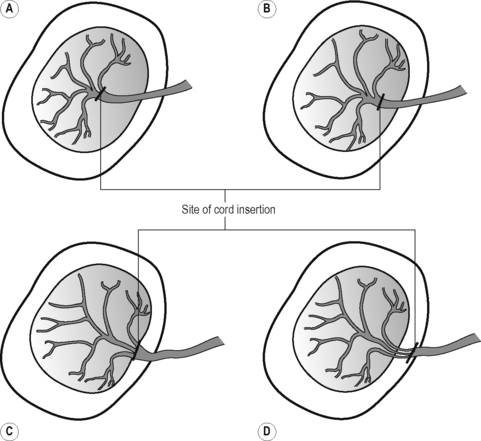

Blood vessels, branches of the umbilical vein and arteries are clearly visible, spreading outwards from the point of cord insertion, usually centrally or slightly off centre (Fig. 33.2A,B). A cord inserted at the edge of the placenta – a ‘battledore’ insertion (Fig. 33.2C) – is usually insignificant, although the attachment may be fragile, increasing the risk of detachment during controlled cord traction. Rarely the cord is inserted into the membranes – a ‘velamentous’ insertion (Fig. 33.2D) – with vessels running through the membranes to the placenta. The attachment can be very fragile, resulting in detachment during controlled cord traction. The vessels may overlie the cervix (‘vasa praevia’) and if ruptured during spontaneous or artificial rupturing of the membranes will result in massive fetal haemorrhage.

|

| Figure 33.2 • Cord insertions. A Central. B Eccentric. C Battledore. D Velamentous |

The umbilical cord contains the two umbilical arteries and the umbilical vein, surrounded by Wharton’s jelly, and is covered by the amnion. A cord with fewer than three vessels may indicate a congenital abnormality; the baby should be referred to the paediatrician and a sample of the cord may be required for analysis. The cord is 40–50 cm long (range 30–90 cm), 1–2 cm wide and is twisted spirally to provide some protection to the vessels from pressure. A short cord is one measuring less than 40 cm and is usually insignificant unless very short when descent of the fetus through the pelvis will cause the cord to be pulled taut and apply traction on the placenta. A long cord may become wrapped around the fetus or knotted, resulting in occlusion of the vessels. The risk of cord presentation and prolapse increases with a long cord, particularly if the presenting part is poorly applied to the cervix. False knots can occur when the blood vessels are longer than the cord and form a loop in the Wharton’s jelly; these are of little significance. A thick or thin cord may be difficult to clamp securely following delivery.

The amnion and chorion comprise the fetal membranes, which appear fused but are not. Stripping one from the other can separate them; the amnion can be pulled back to the cord. The amnion is smooth, translucent and tough, whereas the chorion is thick, opaque and friable. The chorion begins at the edge of the placenta and extends around the decidua. Following delivery, the membranes will have a hole in them through which the baby has been born. If the membranes appear ragged, a piece of membrane may be retained in utero

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access