13. Principles of hygiene needs

for the baby

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Newborn skin95

Skin cleansers/bath additives96

Cord care104

Role and responsibilities of the midwife105

Summary105

Self-assessment exercises105

References105

LEARNING OUTCOMES

Having read this chapter the reader should be able to:

• discuss the role and responsibilities of the midwife in meeting the hygiene needs of the baby

• discuss the rationale for not using soap or bath additives

• discuss the principles of bathing and washing the baby

• describe the methods used for applying a non-disposable nappy.

The midwife has a pivotal role in educating and advising new parents on aspects of caring for their baby and helping them adjust to their new role. Women are often keen to develop the skills of caring for the baby and quickly have to learn how to change the nappy and bath the baby. However, Wray (2006) found that two-thirds of women (50% were primiparous women) were not shown how to change their baby’s nappy or undertake a ‘top and tail’ and that 34% were not shown how to bath their baby. Although this may not be a requirement for all women, primiparous women may not have pre-existing knowledge and experience of these subjects to help them, which might add to their anxieties and insecurities of becoming a new mother. This chapter focuses on the hygiene needs of the baby, specifically bathing and washing, and cleaning of the genital area, the cord and the eyes. While oral hygiene is important for the baby who is unwell, it is rarely needed for the healthy baby and will not be discussed further.

Newborn skin

The skin of the term newborn baby differs from that of an adult in a number of ways and is more delicate, increasing the risk of allergic and irritant reactions occurring. In particular, the epidermis is thinner, the protective lipid film changes after a few weeks and the secretion of sebum lessens as it is replaced by lipids of cellular origin. The lipid structure of the epidermis allow the skin to be semi-permeable thus water can pass through the skin from the baby and substances can be absorbed from the outer surface of the skin (Atherton, 2005, Hale, 2007 and Hopkins, 2004). During the neonatal period both the epidermis and dermis develop further, and there is a change in the skin’s desquamation and pH surface (Steen & Macdonald 2008). Trotter (2006) agrees that the newborn skin can be easily damaged and compromised, suggesting two main causes are the destruction of the skin’s barrier from delipidization (removal of lipid or fat molecules) within the top layer of the epidermis and the stimulation of an inflammatory immune response. A damaged epidermis allows more fluid to pass through the skin, which can result in dry skin further increasing the risk of sensitisation and infection (Trotter 2006).

Some babies, particularly postmature ones, have dry skin, which can crack. Although there is a temptation to rub in substances such as olive oil or emollients in an attempt to ‘moisturize’ the skin, Trotter (2004) cautions against this practice as the dry layer will peel off within a few days revealing a healthy layer of skin underneath, which will then require 2–4 weeks to gain its protective barrier. Steen & Macdonald (2008) agree, advising against the use of emollients or creams on the skin during the first 2–4 weeks. A further concern is that the effects of absorbing creams and emollients at such a young age are unknown. Walker et al (2005) warn that olive oil has been found to reduce the skin barrier function in mice, although it is not known if this is true for humans.

Skin cleansers/bath additives

Although water will wash away the majority of matter accumulating on the baby’s skin, some substances may be fat soluble, and are more easily removed by water once they have been emulsified by a mild cleanser. Thus there is a place for using cleansing agents when washing or bathing adults and children. However, the cleansers work by suppressing the surface tension keeping the fatty substances on the skin; if this is excessive there is a risk of trauma occurring to the skin surface which is increased for the newborn baby’s more delicate skin and can result in allergic and/or irritant dermatitis (Steen and Macdonald, 2008 and Trotter, 2006).

Frequent bathing, particularly if alkaline soaps or lotions are used, may also predispose the baby to infection. An acidic skin surface – the ‘acid mantle’ – affords some protection against infection; a pH <5.0 has bacteriostatic properties (Blackburn 2007). At birth the baby’s skin is alkaline, with a pH of 6.34, reducing to 4.95 within 4 days (Lund et al 1999). Following a bath in which an alkaline soap or bath additive is used, the skin pH increases, becoming less acidic and it may take up to an hour to regain the acid mantle (Blackburn 2007) during which time the skin is more vulnerable to microorganisms. It is advisable to undertake a bath using just warm water, as this is usually sufficient to clean the baby.

There is a lack of good researched evidence evaluating the effects of soaps and cleansers on the newborn skin (Walker et al 2005) and consequently NICE (2006) advise that cleansing agents should not be added to bath water or medicated wipes or lotions used when cleaning the baby during the first 2–4 weeks. Hale (2008) suggests it can take 2–4 weeks for the term baby’s skin to develop the protective barrier with premature babies needing longer. Substances added to the bath may also be absorbed through the skin, which may increase the risk of future allergic sensitisation to topical agents (Blackburn, 2007 and Lund et al., 1999). Simon & Simon (2004) suggest that the use of soaps and cleansers may increase the risk of omphalitis. Thus, if cleansers, wipes or soaps are to be used, they should have a neutral pH, with little or no perfume or dye added and be specifically designed for babies (never use an adult product). Hopkins (2004) suggests a compromise when parents want to use bath additives or cleansers of alternating between bathing with water only and the use of cleansers. However, bathing babies in hard water may also increase the risk of eczema occurring (Hopkins, 2004 and Steen and Macdonald, 2008).

Baby bathing

There is no consensus about the timing of the first bath; it is in part dependent on the condition of the baby and the staffing levels of the maternity unit. A healthy term baby may be bathed shortly after birth, although in many maternity hospitals this is delayed until the baby and woman are transferred from the delivery suite to the postnatal ward or home. The rationale for the timing of the first bath centres mainly on concerns over the risks of the baby becoming cold and the risk of transferring infection.

Johnston et al (2003) recommend delaying the first full bath until feeding is established to minimise the risks of the baby becoming cold, which they suggest may be towards the end of the first week. Steen and Macdonald (2008), however, suggest that bathing can take place once the baby’s temperature has stabilized above 36.8°C. Newell et al (1997) advise delaying the bath until the baby has acquired his own skin flora, considering that this may reduce the risk of infection (although this will be affected by the use of cleansers). Equally, early bathing may be advocated to reduce the risk of transmission of blood-borne infection (e.g. human immunodeficiency virus; Penny-MacGillivray 1996). Trotter (2006) advises delaying the bath until the cord has separated as she considers this can interfere with the physiological process of cord separation.

The parents should be involved as much as possible, and be given the opportunity to bath their baby if they choose to, or be shown how to bath their baby if they have not had prior experience. Parents with little or no experience of handling babies may not feel confident to bath them until they are more confident holding them, thus it is important that the midwife considers the needs of the parents and supports them accordingly Often, a big concern of the parents is that they may drop the baby in the water. If they express this concern, the midwife should ask them what they would do if this happened. Invariably the response is ‘I’d pick the baby up’. This can then lead to a discussion of how to bath the baby safely and help the parents recognise what they would do if something unexpected occurred.

Whereas it is important to minimise the risk of infection, it is not necessary to bath babies every day, nor is it necessary to wash the baby’s hair with each bath. For some parents, daily bathing may be an easier and more pleasurable option than washing the baby. However, Steen & Macdonald (2008) advise that when the baby is immersed in water the superficial layers of the skin hydrate and thicken with an associated reduction in cellular cohesion. Thus, skin that is overhydrated from frequent or prolonged bathing becomes more fragile increasing the risk of trauma occurring to it (Hale, 2007 and Hopkins, 2004). Consequently Steen & Macdonald (2008) recommend that immersion in the bath should last no longer than 5 minutes.

There is no right or wrong way to bath a baby, although it is important to adhere to certain principles:

• keep the baby warm

• keep the baby secure and safe

• use warm water: the temperature should be neither too hot (which risks scalding the baby) nor too cold.

Keeping the baby warm

As babies lose heat quickly when undressed or wet, both the room and water temperature should be warm and the baby bathed quickly, without unnecessary exposure. Additionally, convective heat loss can be minimised by closing windows and switching off fans to stop draughts. Warming clothes, towel and surfaces (e.g. changing mat) minimises conductive heat loss. Drying the baby quickly, particularly the head, reduces evaporative heat loss, and ensuring the baby is not bathed close to cold surfaces such as windows minimises heat loss via radiation.

Security and safety

The bath should be filled initially with cold water to prevent the bottom of the bath from becoming too hot. Also, it reduces the risk of other children scalding themselves should they play with the bath water as it is filling. The bath should not be more than half full. The baby should never be left unattended and should always be held to prevent the head from submerging. A woman with epilepsy should place the bath on the floor rather than on a stand and should not be alone. Following a caesarean section, the woman will have difficulty lifting the baby and equipment and will require help. It may be advisable to use a jug to fill and empty the bath as lifting even a small bath half full with water may result in muscular damage.

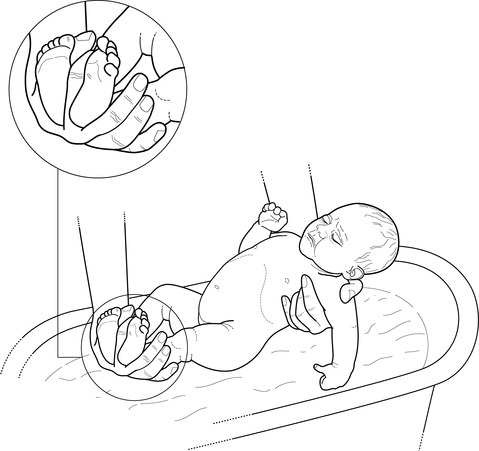

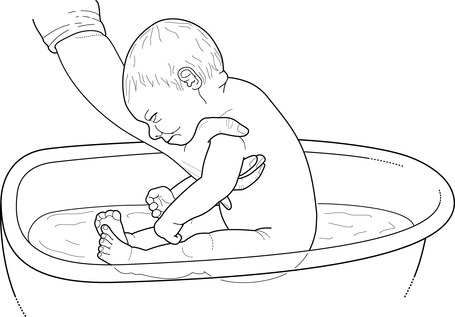

When washing the face and hair, the baby is wrapped securely in a towel and held under the non-dominant arm, secured between the arm and body, with the head and neck supported by the non-dominant hand. To place the baby in the bath, support the baby’s head and neck across the forearm and wrist of the non-dominant hand, encircling the forefinger and thumb around the top of the baby’s arm. The dominant hand grasps the ankles to lift the baby in and out of the water (Fig. 13.1). The baby can be sat up to wash his back by supporting his head across the wrist or forearm of the dominant hand (Fig. 13.2), then returning the baby to the original position.

|

| Figure 13.1 • • Positioning of the hands when placing a baby in the bath |

|

| Figure 13.2 • Positioning of the hands when washing the back of the baby in the bath |