Principles of drug administration

Epidural analgesia

Learning outcomes

Having read this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• discuss the differences between epidural, spinal and combined spinal epidural analgesia

• list the indications and contraindications for epidural analgesia

• discuss the side effects and how these are recognized and managed

• discuss the complications and how these are recognized and managed

• describe how an epidural is sited and a bolus administered

• describe how to remove an epidural catheter safely.

• discuss the role and responsibilities of the midwife throughout and following the procedure

Epidural analgesia generally appears to be an effective way of reducing pain during labour (Simmons et al 2012); it involves the administration of drugs into the epidural space which generally cause loss of pain and loss of sensation. A 24-hour epidural service is offered in most consultant delivery units using skilled obstetric anaesthetists and midwives who have been trained and are considered to be competent in epidural management with annual recertification to ensure their knowledge and skills are maintained (OAA/AAGBI 2013). The epidural rate in the UK is around 22% (Kemp et al 2013), although Odibo (2007) suggests the demand is closer to 70–90%; rates in the US are much higher than the UK at 58% (Simmons et al 2012). It is a useful analgesia in situations where operative surgery may be required as an effective epidural should be topped up and used as the intraoperative anaesthesia (McClure et al 2011). Halpern et al (2009) recommend that the incidence of a general anaesthetic being required as anaesthesia for caesarean section when the woman already has an epidural in situ should not be more than 3%.

This chapter clarifies the terminology and details the procedures for epidural insertion, intermittent bolus administration and removal. The indications, contraindications, side effects, complications – recognition and management – and midwife’s role and responsibilities are discussed. The reader is encouraged to be aware that the debates surrounding epidural use and normal birth are greater than this text can examine.

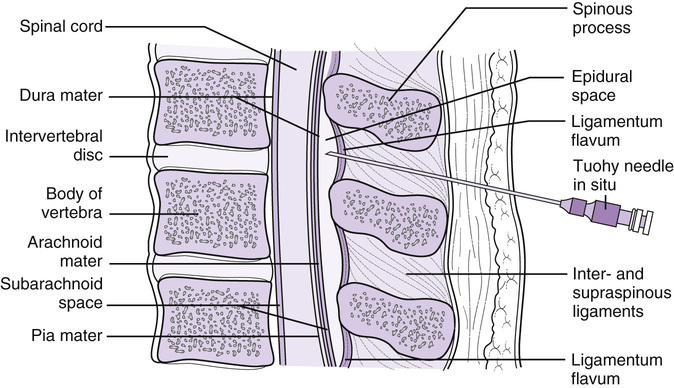

The epidural space

The spinal cord is protected by three meninges (membranes) made of connective tissue with spaces between them – the tough outer dura mater, the arachnoid mater (the main physiological barrier for drugs passing between the epidural space and the spinal cord), and the inner, more delicate, pia mater. Between the pia and arachnoid mater is the subarachnoid space (also referred to as the intrathecal space) containing the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF); the subdural space is between the dura and the arachnoid mater. The meninges are surrounded by a layer of fat and connective tissue contained within the epidural space which is situated between the wall of the vertebrae and ligamentum flavum and the dura mater (Fig. 25.1). The epidural space is a potential space, 5–6 mm thick in the lumbar region, containing blood and lymphatic vessels. According to Sharma et al (2011), the mean distance from the skin to the epidural space is 5.4 mm, whereas two decades ago it was 4.8 mm, reflecting increasing obesity levels. The spinal nerves also pass through the epidural space and intervertebral spaces; the area of skin relating to where each nerve emerges is a dermatome.

Epidural analgesia

This involves the introduction of a local anaesthetic, often combined with an opioid, into the epidural space through a small catheter either as a continuous epidural infusion (CEI) or an intermittent epidural bolus (IEB). Some of the drug can enter into the systemic circulation or attach to the epidural fat content (with no analgesic effect). The remainder of the drugs cross the dura and arachnoid mater into the intrathecal space and the CSF (Bowrey & Thompson 2008).

Successful placement of the epidural catheter is essential if effective analgesia is to be achieved. The anaesthetist has to estimate the distance from the woman’s skin to her epidural space, as this varies between women. Sharma et al (2011) suggest that ethnicity and body mass index are two main factors affecting distance suggesting Asian (including Chinese) women, who have smaller spinous and transverse processes but larger vertebral bodies compared with Caucasian women, have a shorter skin-to-epidural space distance. They also found that the distance was further in Black/British Black and Chinese labouring women who had a body mass index (BMI) >40. The risk of a dural puncture occurring is increased if the distance to insert the epidural needle is overestimated. Ultrasound imaging is being used more frequently for measuring the skin to epidural space distance where there is concern (Loubert et al 2011).

Low-dose ‘mobile’ epidural

Some hospitals use low-dose epidurals which provide good analgesia without loss of motor function. While this is referred to as a ‘mobile’ epidural women are usually restricted in how they can mobilize – moving between the bed and a chair. As full motor strength is not guaranteed, women should be cautioned not to walk around. The observations recorded are the same as for a normal-dose epidural with the addition of assessing the woman’s ability to ambulate 20–30 minutes after each bolus. This is assessed by asking the woman to raise each leg straight off the bed and hold its position for at least 5 seconds – if this is achieved weight bearing is likely to be satisfactory.

Spinal analgesia

Spinal analgesia is achieved by injecting a single bolus of the drug/s through the epidural space, dura and arachnoid membranes, into the intrathecal (subarachnoid) space. Lower doses of the drug(s) can be used as it is placed directly into the CSF where the opioid can bind to the opioid receptor sites in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Onset of analgesia is rapid but not as long lasting as an epidural and therefore is rarely used for labour on its own (Simmons et al 2012). It is often the analgesia/anaesthesia of choice for emergency caesarean section where rapid anaesthesia is required or for an elective caesarean section. Spinal anaesthesia may be used for emergency caesarean section if the epidural block is insufficient, although Vaida et al (2009) advise caution if a bolus has just been administered. They suggest the CSF may be compressed so when the drugs are injected in the intrathecal space, they may be displaced upwards which can lead to an unpredictable high block. This is not an issue with a continuous infusion.

Combined spinal epidural analgesia

Combined spinal epidural (CSE) analgesia involves a spinal injection of a small amount of local anaesthetic and/or a lipophilic opioid, e.g. fentanyl, into the intrathecal space immediately before or after the placement of the epidural catheter. This can be achieved by using the epidural needle to locate the epidural space at the level of L3 then passing a smaller-diameter longer spinal needle through the epidural needle lumen to pierce the dura and arachnoid membranes. The drug is injected into the CSF and the spinal needle removed to allow the epidural catheter to be inserted into the epidural space for maintenance of analgesia (Loubert et al 2011, Simmons et al 2012). Anim-Somuah et al (2011) suggest CSE combines the advantages of the faster onset and more reliable analgesia achieved with the spinal with the continuing pain relief of the epidural while allowing the woman to remain alert; however, there is a greater incidence of pruritus than with epidural analgesia alone (Loubert et al 2011). Simmons et al (2012) suggest there is no advantage in offering CSE over epidural for labour analgesia.

Drugs

Local anaesthetics (e.g. bupivacaine, ropivacaine) cross the dura and arachnoid membranes, where they are in contact with the nerve roots and spinal cord. Once there, they plug the sodium channels and dampen down the excitation of the nerve cell, preventing it from passing the impulse to another nerve cell. This prevents transmission of the pain impulses to the higher centres and can take effect within 10–20 minutes of administration.

The combination of a local anaesthetic and a strong opioid in low doses infused into the epidural space is synergistic with the potential to produce analgesia without increasing the incidence of side effects seen when the drugs are administered separately at higher doses (Bowrey & Thompson 2008).

Opioids bind to opioid receptors, primarily mu opioid receptors, in the dorsal horn. They inhibit the release of neurotransmitters such as substance P and glutamate, further reducing the transmission of the pain impulses as well as producing an analgesic effect. Fentanyl is 75–125 times more potent than morphine because it is lipophilic (fat-soluble) (Bowrey & Thompson 2008) but has a shorter duration and half-life.

Continuous versus intermittent drug administration

CEI provides a constant flow of a small amount of the drug(s) into the epidural space via an epidural infusion pump, whereas IEB is in the form of manually administered boluses given either on a regular basis or as needed. Boluses can also be provided as an adjunct to continuous administration via the pump. George et al (2013) suggest that small, regularly spaced boluses provide a more extensive spread of local anaesthetic within the epidural space which may result in improved analgesia. Skrablin et al (2011), however, propose that CEI provides a more consistent analgesia without excessive fluctuations in anaesthetic level than IEB but is also associated with insufficient or excessive analgesia and blockade.

Contraindications

Some of the contraindications for epidural analgesia are absolute while others are relative:

Side effects of epidural analgesia

The side effects associated with epidural analgesia usually result from the effects of the drugs used:

Opioid side effects:

Local anaesthetic side effects vary depending on the drug and dosage used:

Women with an epidural are also more likely to develop a fever during labour than women who do not have an epidural (Segal 2010) although the aetiology for this is not clear. It is possibly multifactorial, a combination of an imbalance between heat production and heat-dissipating mechanisms, a side effect of opioids, particularly fentanyl, and maternal inflammation; the latter is now the dominant view (Segal 2010).

Management of side effects

Respiration depression

Although this can occur early, within the first 2 hours of drug administration, it may also be a late and unreliable sign of opioid overdose (6–24 hours). It occurs as a result of the opioid being absorbed from the epidural space into the systemic circulation and the intrathecal space. It is likely that there is a rostral/cephalad spread of the opioids which means it spreads towards the head with the brain stem and respiratory centre being reached early in the spread. The effect is more profound with morphine and diamorphine (as they are water-soluble) than fentanyl.

Bowrey & Thompson (2008) define respiratory depression as a respiratory rate <8 and an increased sedation score on two occasions after the administration of spinal opioids. An increasing sedation score may be noted before the decrease in the respiratory rate. Monitoring the sedation level and respiration rate is important for anyone who has received opioids so that respiratory depression is detected and treated early. The woman should be kept upright, given oxygen (titrated to maintain oxygen saturation levels ≥95%), help called and naloxone administered. As the effect of naloxone wears off after approximately 1 hour, further doses may be required.

Sedation

Opioids can cause sedation, which for some women is very welcome and allows them to rest, even sleep, throughout labour. The woman’s sedation level should be monitored with the vital signs as an increasing sedation level may herald the onset of respiratory depression.

Nausea and vomiting

Low doses of opioids activate the mu opioid receptors in the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), which can result in nausea and vomiting although the effects are not as evident as when opioids are administered intravenously. Not all women will experience nausea and vomiting, as higher doses of opioids can suppress vomiting by acting at receptor sites deeper in the medulla. Where it does arise, it is usually managed easily with the administration of an intravenous anti-emetic.

Pruritus (itching)

This occurs more commonly over the face, chest, and abdomen. It may be a result of the opioids causing histamine release or a side effect from the activation of the mu opioid receptors. Treatment is administration of an antihistamine with or without a decrease in the infusion rate if a CEI is used or if severe, administration of a small dose of naloxone – however this will decrease the analgesic effect of the opioid.

Urinary retention

If the woman is unable to pass urine (usually encouraged by sitting on a bedpan) then insertion of an indwelling urinary catheter may be required (see Chapter 14).

Hypotension

Hypotension can occur due to the action of the local anaesthetic on the sympathetic nerves by relaxing the smooth muscle of the blood vessel walls and reducing the tone, which results in vasodilation. Hawkins (2010) suggests it affects up to 80% of women undergoing an epidural. It is important to establish the woman’s baseline blood pressure before the epidural commences. Hypotension is usually easily treated by fluid replacement; thus it is important the woman has a peripheral intravenous cannula in situ. If this is ineffective, a vasopressor such as phenylephrine or metaraminol may be required either as a bolus or by infusion. The midwife should also consider turning the woman to a left lateral position until the hypotension is corrected. Correcting hypotension is important as the drugs cause a decrease in vascular resistance and with a normal blood pressure there is a significant improvement in uteroplacental blood flow (Hawkins 2010).

Leg weakness

The woman is advised not to mobilize following birth until she has full leg strength and is able to weight bear. The midwife should be with the woman when this is first attempted. With reduced mobility the woman is at increased risk of a pressure injury, particularly around the heels (Loorham-Battersby & McGuiness 2010), and the midwife should take appropriate precaution to minimize this risk (see Chapter 53). Increasing leg weakness noted in labour or after delivery may be associated with an infusion rate that is too high, epidural haematoma or abscess, particularly if the effects of the epidural on the motor block have been decreasing. If there is any concern about a haematoma forming during labour the epidural infusion should be turned off and no further boluses given and leg strength assessed every 30 minutes – an increase in leg strength should be seen and the infusion/bolus administration can recommence. The same applies if the woman is receiving epidural analgesia postnatally.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree