2. Principles of abdominal examination

during the postnatal period

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Physiology of involution19

Role and responsibilities of the midwife22

Summary22

Self-assessment exercises22

References22

LEARNING OUTCOMES

Having read this chapter the reader should be able to:

• briefly outline the physiology of involution

• discuss the possible deviations from the norm that can be identified when palpating the uterus postnatally

• describe the procedures (verbal and physical) necessary to assess involution of the uterus

• discuss the role and responsibilities of the midwife when undertaking abdominal examination during the postnatal period.

Gale (2008: 281) believes that postnatal care is ‘…vital because it prepares parents for a lifetime of parenting’. Postnatal morbidity is something for which many women are unprepared; without adequate care, it is also something for which mortality is a possibility. Depending on other indicators, assessment of the uterus postnatally is one aspect of care that the midwife can undertake as part of holistic and individualised postnatal care. This chapter includes a description of the physiology of uterine involution and discussion of the ways in which normality is assessed.

Physiology of involution

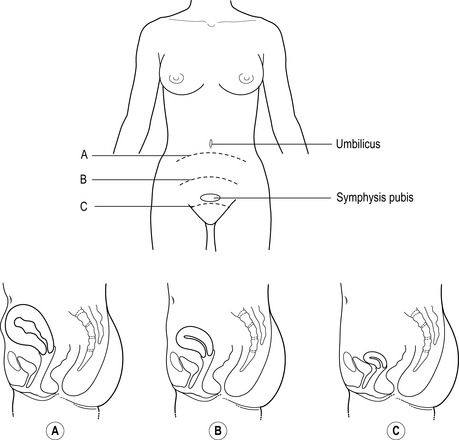

Involution is the process by which the uterus returns approximately to its pre-pregnant size, position and tone. This involves a reduction in weight from 1000 to 60 g and reduction in size from 15 × 11 × 7.5 cm to 7.5 × 5 × 2.5 cm. The term ‘autolysis’ refers to the digestion of excess muscle fibres by proteolytic enzymes, a process that is assisted by the continuing contraction and retraction of the uterus that began during labour. As the uterus reduces in size, the decidua is shed within the lochia (the discharges from the vagina following childbirth) and new endometrium begins to grow from the basal layer of the endometrium. New endometrial growth is evident from about the tenth day after delivery; by 6 weeks the endometrium has reformed. Strong contraction of the muscle fibres occurs in the first 12–24 hours, decreasing in strength and frequency over the next few days. They are often stronger and persist for longer in multiparous women (Blackburn 2007). Women recognise these contractions as ‘after pains’. The rate at which the uterus involutes is considered to be approximately 1 cm per day. Therefore, after 6 days, the fundus is usually about halfway between the umbilicus and the symphysis pubis and should be just palpable by the end of 10 days. For many women, the fundus may not be palpable at this time, and is usually no longer palpable after the twelfth postnatal day (Fig. 2.1).

|

| Figure 2.1 • The position of the uterus during involution. A Following delivery. B 1 week after delivery – the fundal height is palpable approximately 5 cm above the symphysis pubis. C 2 weeks after delivery – the fundal height is not usually palpable above the symphysis pubis |

Whereas most textbooks report the changes described here as standard postpartum physiology, Cluett et al (1997) noted several variations in their assessment of 28 women, including several days without uterine involution and uteri palpable at 23 days, both without signs of abnormality. Subinvolution of the uterus is considered to be less likely if the mother is breastfeeding (due to the increased action of oxytocin on uterine fibres) but more likely if there has been surgery or trauma. Pathological subinvolution usually relates to endometritis (infection within the uterus), often stemming from retained products. This creates the potential risk of a secondary postpartum haemorrhage (PPH).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree