Chapter 2. Primary health care

principles and practices

Introduction

Primary health care (PHC) is a pathway to achieving basic human rights, which is essentially social justice. Since the Declaration of Alma Ata in 1978, PHC has been both a philosophy and organising framework for nurses, midwives and other health professionals. As a framework, PHC circumscribes nursing and midwifery activities in terms of illness prevention, health promotion, and structural and environmental modifications that support health and wellness. This does not exclude the important work in caring for those experiencing illness or disability. It does, however, shift the caring agenda to the social determinants of health (SDOH), in primary care settings such as general practice, in critical or acute care, home care, rehabilitation settings, residential care, or in working to modify the community itself. As we mentioned in Chapter 1, health, illness prevention, and recovery from illness and injury, are socially determined; that is, created and maintained in the social environments and settings where people live, play, work, are educated, worship and interact with others.

PHC is both a philosophy of care and an organising framework for nurses, midwives and other health professionals.

The overarching principles embodied in PHC guide us to work towards equitable social circumstances, equal access to health care, and community empowerment through public participation in all aspects of life. This approach includes being culturally sensitive to diversity in people’s lifestyles, preferences and situations. PHC is focused on promoting healthy social and structural conditions for good health. These conditions include health literacy and citizen participation so that people are empowered to make informed choices to develop their personal and community capacity. For individuals, developing health capacity means becoming health literate, knowing where and how to access and maintain health knowledge and skills, feeling comfortable in participating in discussions or activities about health, and having supportive, sustainable resources to support empowered health and lifestyle choices.

Working with community networks and organisations committed to capacity building development demonstrates nurses’ and midwives’ accountability to the community and to partnerships for good health. The outcome of community partnerships should be better health, equity, justice, and good governance in health services, including appropriate, effective, and efficient use of available technologies. To guide this work, we use the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (World Health Organization, Health and Welfare Canada & CPHA 1986). The Charter is a framework that encapsulates the goals of PHC, and we outline how this can be helpful in practice throughout the chapter. Because the principles of PHC are not uniformly understood, this chapter also provides an explanation of the PHC principles and how they fit with community health promotion. This is aimed at encouraging common understandings and a common framework for working with communities. We also explain the relevant historical moments in health promotion, to illustrate how our thinking has been shaped by new knowledge and new understandings of communities. In this discussion we will also revisit the SDOH, particularly those which either foster or compromise social justice and community empowerment.

The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion provides a framework for health promotion that health professionals can use to enact the goals of PHC.

Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

1 explain the terms ‘primary health care’, ‘primary care’, ‘primary, secondary and tertiary prevention’

2 analyse the principles of PHC in relation to community health and wellness

3 identify primary, secondary and tertiary prevention activities in promoting community health

4 explain the difference between health promotion and health education and the significance of each in community health

5 discuss the application of PHC principles to the strategies of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion

6 devise a strategic plan to address population health in a given community using the Ottawa Charter as a guide.

Clarification of terms

PHC is a term that is sometimes confused with other, similar terms, such as primary care and primary prevention, so to ensure clarity, this chapter begins with some definitions of terms.

Primary health care (PHC)

PHC encompasses a broad spectrum of activities to encourage health and wellbeing. These can include primary (initial) care and include follow-up activities for promoting the health of the community, protecting community members from harm, and/or preventing illness or injury. Importantly, the ultimate goal of PHC is to build community capacity to enable sustainable health and wellbeing. Community capacity building is based on the fundamental values of equity, community participation and self-determination, which embody human rights and shared social expectations (WHO 2008).

Primary health care is a philosophy of care intended to redress inequities in health by recognising that wellbeing is dependent on a broad range of social, political, economic and environmental factors.

Two types of PHC have been described in the literature. ‘Selective primary health care’ is a term that emerged in the 1980s under neoliberal economic policies that emphasised medical and technical solutions to health problems (Baum 2007; deVos et al 2009). Health was seen as an investment, and selective PHC was aimed at ‘best investments in health’; ensuring that the health care system funded programs that would have a significant effect on certain groups in the population. The language of selective PHC was typical of the economic policies of the time. Certain population groups were seen as ‘targets’. Health care was ‘outcome focused’. Health planning was ‘target oriented’, and success was defined in terms of concrete health improvements linked to specific expenditures (deVos et al 2009:122). Selective PHC did not build sustainable communities, but led to fragmentation of services, draining expertise and resources (Baum 2007). However, today, selective PHC is seen as focusing on a specific group with high priority needs within the broader context of comprehensive PHC (Baum et al 2009).

‘Comprehensive primary health care’ adopts a community development approach, which is more closely aligned with the social justice agenda. Comprehensive PHC revolves around an empowerment framework, where community members work in partnership with health professionals to participate fully in health decision-making (Baum, 2007, Baum et al., 2009 and deVos P, et al 2009). This shifts the agenda from professional control over decisions about priorities and resources, to one where community empowerment is the main objective. Members of the community are not beneficiaries of health services, but rather have the power to control resources and how they are distributed, which is aimed at creating equitable conditions (Baum 2007; deVos et al 2009). Throughout this text PHC will refer to comprehensive PHC.

Primary prevention is aimed at maintaining health and preventing illness, secondary prevention is aimed at treating and limiting illness or injury, and tertiary prevention is aimed at rehabilitative or restorative actions.

Primary, secondary and tertiary prevention

As mentioned previously, prevention is a major focus of PHC. Leavell and Clark’s (1965) three levels of prevention are widely accepted as encompassing the range of activities involved in preventing illness or injury. These levels, primary prevention, secondary prevention and tertiary prevention, distinguish between strategies aimed at maintaining health and wellbeing and preventing illness (primary), treating and limiting illness or injury (secondary), and rehabilitative or restorative actions (tertiary). The aim of primary prevention is to promote health by removing the precipitating causes and determinants of ill health or injury. This can include vaccinating children against communicable diseases, health education and promotion of healthy lifestyles in areas such as personal nutrition, rest, exercise and companionship, and protecting the physical, social and cultural environments. Secondary prevention usually refers to steps taken to recover from illness, to guard against any deterioration in health, screening for early detection and treatment of disease, and any measures to limit disability. Tertiary prevention is restorative. Programs revolve around rehabilitation, transitions to community care and education for industry support programs (Leavell & Clark 1965).

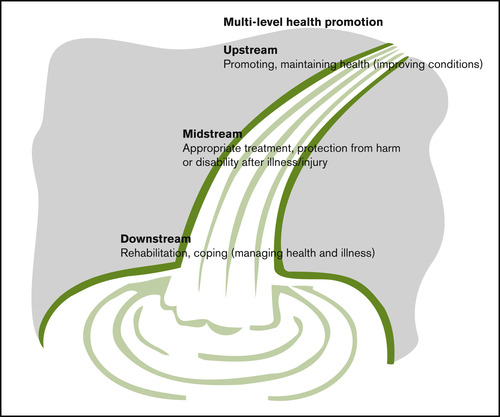

Conceptualising health professionals’ activities across these three levels indicates a holistic, PHC approach that can be applied across the life span. The metaphor of a waterfall illustrates. Primary prevention activities at the community level are ‘upstream’ actions, such as developing educational materials to portray the benefits of nutrition or regular exercise to help individuals stay healthy. Besides offering encouragement for healthy lifestyles, primary prevention includes lobbying the local council or government agencies to create the conditions that support community health and development. This type of activity might include helping secure cost-effective foods or safe spaces for children to play. Secondary, or ‘midstream’, prevention includes such preventative activities as screening for skin cancer, conducting mammography clinics, or establishing drop-in centres for adolescents or isolated older people. Tertiary prevention occurs ‘downstream’ and typically involves providing assistance or information to help people cope with a potentially disabling condition. This could involve the establishment of walking programs for those who have had a cardiac incident, support groups for family members coping with a loss, or any measure that helps ensure continuity of care and health literacy, such as access to timely health advice (see Figure 2.1).

Primary care

When people require health care because of injury or illness, the first line of care is primary. So primary care is the initial decision as to what must be done and it usually guides the subsequent management of a person’s condition or needs. Primary care may involve only one intervention, or treatment over an extended period of time, but it is still primary, in that it is aimed at helping people with whatever problem required care in the first place. Physicians, nurses, paramedics, dentists, physiotherapists, complementary therapists and a range of other health professionals may provide the initial care.

An ambulance officer or paramedic may be first on the scene to deal with a road accident or injury; a physical education teacher, trainer or school nurse may be the first line of care in the recreational setting. Each would provide care and then would likely refer the person needing assistance to a physician who would assume the role of primary care provider. Paramedics, by nature of their role in responding to emergencies are quite often the primary care providers, usually in a life-saving capacity.

Similarly, nurses in a hospital emergency department or in a community clinic may provide initial treatment for an emergency, then either refer the patient to the local medical practitioner to manage the condition, or manage it themselves, depending on the situation. In the latter case, the nurse would be acting as a primary care provider. This role is often enacted by nurses and nurse practitioners in remote locations where there is no medical practitioner. There is also some discussion internationally regarding an expanded paramedic role. Given that paramedics often follow up primary care by providing care in a person’s home, there is growing acceptance of reframing the role of the ‘paramedic practitioner’ who provides a brief initial intervention and then appropriate referral (Stirling et al., 2007 and Woollard, 2006).

Another situation where someone other than a medical practitioner acts as primary care provider is in the workplace. Many manufacturing and mining companies, for example, employ nurses or other health professionals to manage occupational health and safety. For some workplace-based problems, the occupational health professional may be the most appropriate and available person to provide primary care. However, in addition to primary care, this role differs from the paramedic role in that it extends beyond ‘nursing in the community’ to ‘nursing the community’, as we mentioned in Chapter 1. Whereas the paramedic or other emergency personnel provide acute and sometimes ongoing care ‘in the community’, the occupational health nurse provides care of the occupational environment as well, which is ‘nursing the community’. This role will be elaborated on further in Chapter 4.

The model of primary care most people encounter is that of general practice. Most general practitioners (GPs) provide primary care and variable levels of follow-up of patients and families, depending on many factors. These factors include the time pressures of the practice, especially where there are staff shortages, demand and preferences of the practice clients, and the health care system in which the practice operates. In some countries such as Australia and Canada, general practice operates on a ‘fee-for-service’ basis, with reimbursement from Medicare for episodes of care.

The model of primary care most people in Australia and New Zealand encounter is general practice.

This system has been described as creating a perverse incentive to provide more, rather than more comprehensive services, because the financial rewards flow from the number of care episodes rather than the quality of care (Australian Nursing Federation [ANF] 2009). In other countries, such as the United Kingdom, primary care is provided under a ‘capitation’ system, where the practice is paid on the basis of the number and type of people enrolled in a practice, or group of practices. In New Zealand, primary care is provided under a mixed system with ‘capitation’ covering most services but with many general practices still charging a fee-for-service to cover the shortfall in capitation funding. As in Australia, general practice in New Zealand is still largely run under a business model and fees for service vary widely. However, when funding is provided on a ‘per capita’ or population basis, as it is in New Zealand, there is a greater likelihood of comprehensive, multidisciplinary, integrated PHC. For this reason, the worldwide trend towards PHC is gradually creating an impetus for general practice to change to this system (Martin 2008; WHO 2008).

New Zealand was one of the first countries in the world to make a strategic commitment to implementing PHC at a national level.

Nurses and midwives in Australia and New Zealand play an important role in the PHC movement. New Zealand was one of the first countries to make a national commitment to PHC (Ministry of Health New Zealand [MOHNZ] 2001), and New Zealand nurses worked hard to ensure their role was clearly identified as crucial to enactment of the new strategy. Evaluation of nursing developments since implementation demonstrate that, despite a range of barriers, there has been substantial growth in some nursing roles and capability in PHC (Finlayson et al 2009). As New Zealand nurses seek out opportunities for improving population health under the PHC strategy’s new funding streams, New Zealand is slowly seeing increasing numbers of nurse-led initiatives in PHC. These include a shift to name all nurses working in PHC ‘primary health care nurses’, increasing numbers of nurse practitioners working in PHC and increasing numbers of nurse-led clinics.

In Australia, recent government policy changes have recognised the important role of practice nurses in broadening primary care to PHC (Halcomb et al 2008). Similar examples of this trend are evident in countries such as Canada, with models of collaborative general practice between GPs and nurses effectively ‘infusing primary care principles in the delivery of PHC’ (Besner 2004:356). These initiatives are consonant with the recommendations of the WHO (2008) that care should be brought closer to people, relocating entry points from hospitals and specialist services to generalist, primary care centres aimed at improving coordination of care.

Public health, population health and primary health care: a brief history

Public health is aimed at preventing disease and promoting the health of populations. Public health initiatives are based on population-level data and typically involve measurement and surveillance, and development of evidence-based strategies to either prevent or overcome diseases. This involves collecting and analysing epidemiological information on the distribution and determinants of health and ill health in a particular community or country, and linking this information to what is known in other populations. One of the problems with this approach is that by aggregating this type of information, the assumption is made that all community members develop or behave in similar ways, thereby creating stereotypes of communities that are actually diverse and changing (Abbott et al 2008).

Population health

Population health is similar to public health in that it is:

The organized response by society to protect and promote health, and so prevent illness, injury, disability and early mortality. The programs, services and institutions of population health emphasise the prevention of disease and the health needs of the population as a whole.

(Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing. Online. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-about)

Primary health care and the Declaration of Alma Ata

Public health and population health approaches can be differentiated from PHC, which is defined in the Declaration of Alma Ata as:

Essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development in the spirit of self-reliance and self-determination. It is the first level of contact with individuals, the family and community with the national health systems bringing health care as close as possible to where people live and work and constitutes the first element of a continuing care process.

The distinctions between public health, population health and PHC illustrate how the ideas of health planners and policy-makers have changed over time. Although the focus of public health has always been to ensure the highest level of health for the greatest number of the population, historically, public health has been about illness, not health. From the 19th century, public health authorities adopted a regulatory approach of surveillance and control to overcome infectious diseases. They tracked epidemics or potential epidemics, and ensured that government regulations were in place for monitoring illness in the population and responding quickly when it was required.

Public health was historically focused on surveillance and tracking infectious disease. This is still an important focus but now public health also includes examining the SDOH and how these affect population health.

Public health was therefore defined according to a biomedical model where the emphasis was on understanding the causes of illness in order to apportion resources appropriately. In the biomedical model the public health focus is on midstream (interventions) and downstream (rehabilitation) activities to manage epidemics and protect people, rather than promote health. This resulted in concentrating resources in hospitals and acute-sector services (Bernier 2005). However, the current focus revolves around the SDOH and how these affect the population. This approach has become incorporated into social epidemiological models of health planning, which will be further explained in Chapter 3.

Problems with the ‘old public health era’

In the biomedical public health era, public health experts were guided by current medical knowledge, political factors and the availability of financial and personal resources. So, for example, in those parts of the world where health personnel and resources were plentiful, people were expected to have higher levels of health. Where vaccines were available and where the politics of the day encouraged medical research through generous funding schemes, diseases should be curtailed. Members of the public rarely questioned the medical experts on any of these public health matters. Yet, no relationship was found between good health and the provision of services. Clearly, there was a need to look for a broader set of criteria for good health.

In 1978 an important international meeting among members of 189 countries culminated in the Declaration of Alma Ata, named after the city in the former USSR where the meeting took place. The Declaration was the first global proclamation that a broader perspective of health was needed to galvanise the efforts of health planners around the world to meet current and future challenges. PHC was declared as the roadmap to achieving better health for all populations. The architects of the Declaration found no opposition to this approach among health professionals.

The Declaration of Alma Ata made the first global assertion that a broader view of health was needed to address health needs. PHC was declared as the vehicle through which better health would be achieved.

Four years earlier, the Lalonde Report in Canada had suggested a more socially contextualised definition of health, including strategies for achieving health that placed less onus on individuals and more emphasis on creating the right conditions in their environments (Lalonde 1974). PHC embodied this idea. It was not only a vision for health, it was seen as a philosophy permeating the entire health system, a strategy for organising care, a level of care (primary or ‘first line’ of care) and a set of activities (Chamberlain & Beckingham 1987).

The Declaration of Alma Ata represented a watershed in public health. Its focus was on empowering people to have control over decisions that affected health in their own families and communities. The PHC approach conceptualised health as a fundamental right, an individual and collective responsibility, an equal opportunity concept and an essential element of socio-economic development (Holzemer 1992). This represented a stark contrast to the historical ‘top-down’ approach to planning for public health in that people at the grassroots level of societies were now to have a greater say in planning from the ‘bottom-up’, or ‘inside out’ instead of ‘outside in’ (Courtney 1995). The PHC approach has been described as keeping health professionals on tap rather than on top; acting as a resource to the community (Baum 2007).

PHC and the social gradient

As the Declaration of Alma Ata became integrated into health strategies throughout the world, in 1980 the UK government published the Black Report on Inequalities in Health (UK Department of Health and Social Services 1980). The report illustrated the extent to which ill health and mortality were distributed unequally among the social classes in the UK. It showed a widening gap between rich and poor, providing clear evidence that health was associated with income, education, diet, housing, employment and other conditions of work. This work was subsequently extended in the ‘Whitehall studies’, which investigated different levels of health among British bus drivers as a function of their level of employment (Marmot, 1993, Marmot and Shipley, 1996, Marmot et al., 1984 and Marmot et al., 1987). The researchers concluded that people’s health status is better with each successive step up a socio-economic gradient, now called the ‘social gradients’ finding (Hertzman, 1999 and Hertzman, 2001).

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s health policies in many countries, including Australia and New Zealand, focused on programs that create, maintain and protect health and wellbeing, through income security, a good education system, a clean environment, adequate social housing and community services (Baum, 2002 and Ministry of Health New Zealand (MOHNZ), 2001). In the

The ‘social gradients’ finding shows that a person’s health is better with each successive step up a socio-economic gradient. In other words, the more you earn, the better your income and the safer your housing, the better your health will be.

PHC and the health promotion charters

The Lalonde Report, the Declaration of Alma Ata and the Black Report, were all important milestones in our evolving policy and research agenda, collectively signalling a shift in thinking from the ‘old public health’, wherein health professionals decided what was best for the community, to a ‘new public health’, where communities themselves decide priorities and preferences for health from where people live, work and play. This PHC vision placed collective action by the community at the centre of health decision-making, with health professionals working as partners to help the community build health capacity. Another significant shift has been the focus on health promotion. This can be linked back to the leadership of Ilona Kickbusch, then Head of Canada’s Health Promotion Directorate, who convened the first WHO International Conference on Health Promotion, in 1986 in Ottawa, Canada. The conference embodied PHC as the new public health, focusing the health promotion discussions on lifestyle factors, living conditions and the environments where people lived rather than health services with the objective of providing health for all (Kickbusch 2003).

A series of WHO sponsored conferences on health promotion have provided strategic direction for development in health promotion for over 20 years.

The Second International Conference on Health Promotion was hosted by Australia in 1988, with an emphasis on healthy public policy. The Third International Conference on Health Promotion was held in Sundsvall, Sweden in 1991, focusing on supportive environments for health. The fourth took place in Jakarta, Indonesia in 1997, culminating in the Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century (see Appendix B). By this time, the influence of economic rationalism had shaped global politics, and the Indonesian meeting focused on health promotion as an investment in overcoming poverty as a major cause of ill health. The Fifth Global Conference on Health Promotion, in Mexico City in 2000 was called ‘Bridging the Equity Gap’. The recommendations from this conference revolved around positioning health promotion as a fundamental political priority in all countries, across all sectors, with information shared freely between nations (Catford 2000). At the end of 2000, eight non-government groups came together in Bangladesh as the First People’s Health Assembly. The meeting culminated in the People’s Health Charter (see Appendix C), which demanded that the WHO eliminate their links with the corporate interests of economic globalisation that had influenced its activities, and focus instead on comprehensive PHC and protection of the natural environment (Baum 2007). Following this, the Bangkok Charter (see Appendix D) arose from the Sixth Global Conference on Health Promotion in Bangkok, Thailand. The conference’s discussions sought to highlight the global development agenda as a core responsibility for all governments, focusing on communities and civil society and the need for good corporate practices (Wilson 2005).

The basis of the original Declaration of Alma Ata and the Jakarta, Bangkok and People’s Health Charters have drawn global attention to the health effects of widespread inequalities (unequal distribution of health resources) and inequities (the moral aspect of health inequality in terms of decisions taken on health care and the distribution of resources) (Asada, 2005, Baum, 2007 and Raphael, 2009). These important statements and those from subsequent international meetings and policy deliberations have been unequivocal in their goal to address the SDOH, and they have been extremely powerful in shaping PHC thinking today. In the 21st century, mainstream thinking in the promotion of health takes the view that without equal access to education, health care, transportation, nutritious food and social support, the world will never have health for all.

The WHO health promotion conferences have drawn global attention to the health effects of unequal distribution of health resources (inequities in health).

From its inception in the 1970s, the PHC agenda has created a legacy to communities of the 21st century, where members of the community, rather than the experts, are squarely positioned at the centre of health care. People in communities, health professionals, educators, engineers, service workers and parents alike are now considered partners and full participants in creating and sustaining health, rather than being recipients of health services (Aston et al., 2009 and Coulter et al., 2008). This renders the notion of ‘consumer’ (the public) and ‘provider’ (the health professional) outdated. Greater sharing of health knowledge, along with enhanced transparency of decision-making represents a more democratised approach to health, one that embodies current thinking in promoting health, that is, comprehensive PHC.

In 2008 the WHO (2008) commemorated the 30th anniversary of the Declaration of Alma Ata by recommitting its PHC agenda in its annual report: ‘Primary health care — now more than ever’ (WHO 2008). ‘Now more than ever’ refers to the state of global health care, which continues to be plagued by inequitable access, impoverishing costs and erosion of trust. Together, these constitute a threat to social stability. The report underlines the need for PHC at a time when the global financial crisis is compromising people’s quality of life, and when our failure to create an equitable world is impinging on human rights (WHO 2008).

Many health professionals are working to embed PHC principles into their practice. Nurses, pharmacists, social workers, nurse practitioners, Plunket nurses, advanced practice and/or remote area nurses and other allied health professionals have a broad, PHC scope of practice, participating with communities to help define their needs and advocate for changes to the social and structural environments. Their roles vary, but their commitment to PHC is a common bond. In a variety of contexts they are promoting equitable access to their services, adopting inclusive practices, fostering public participation and community empowerment, using appropriate technology, collaborating beyond health services to ensure that other sectors of society are contributing to health, and focusing their practice on health promotion as well as appropriate illness care. These are the principles of PHC.

The principles of PHC are accessible health care, appropriate technology, health promotion, intersectoral collaboration, community participation and cultural sensitivity.

PHC principles

PHC is guided by the principles of accessible health care, appropriate technology, health promotion, cultural sensitivity, intersectoral collaboration and community participation. The literature on PHC includes cultural inclusiveness as a common thread in each of these principles. However, we include cultural sensitivity as a separate principle. This acknowledges the important work on cultural safety that has been done over the past two decades in New Zealand. Being culturally sensitive and enabling culturally appropriate health care that protects cultural safety is one of the most important factors in achieving PHC. The principles are interconnected, but they are examined separately below to underline the importance of each to the overall philosophy of PHC.

Accessibility: a case of equity and social justice

As described above the PHC movement that began with Alma Ata was based on the need for social justice, to redress ‘politically, socially and economically unacceptable health inequalities in all countries’ (WHO 2008:xii). More than three decades after Alma Ata many inequities persist. Globally, some progress has been made in reducing mortality and providing access to health care, but there has been a widening gap in income, with increasing health disparities in the most fragile countries of the world, especially sub-Saharan Africa (WHO 2008). Many African families continue to find access to vaccination difficult. Childbirth care and unsafe abortions continue to be problematic, with little access to qualified health care providers. Northern Africa, Asia (including India) and Latin America have had impressive gains, particularly in life expectancy. However, countries such as the Russian Federation and Newly Independent States have seen life expectancy either stagnate or decline, due to widespread poverty and the commercialisation of clinical services (WHO 2008).

The link between poverty and health is now clearly evident in studies on health outcomes. Poverty is a product of the social environment, linked to political decisions (Schrecker 2008). When people live below the ‘poverty line’ of having less than $US2 per day it is called absolute poverty. Being poor in relation to the rest of society is called relative poverty. Many developing countries experience high rates of absolute poverty. Absolute poverty is usually accompanied by high child and adult mortality rates, lower investments in human and physical resources, higher inflation and less trade, less effective disease prevention, and worse educational outcomes and other risk factors that threaten health (Ruger & Kim 2006).

The link between poverty and health is clearly evident in studies on health outcomes. Many developing countries experience absolute poverty while many developed countries experience relative poverty.

Despite networks of PHC facilities provided by the United Nations (UN), many refugees and people displaced by war and conflicts are among the most impoverished and disadvantaged, experiencing absolute poverty in refugee camps (UN 2009).

In many countries of the world, including those considered highly developed, there is a widening gap in access to health services between genders, cultures, Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, and those living in urban and rural or remote areas (WHO 2008). These factors cause relative poverty or a state of disparity between rich and poor. Other outcomes of disparities include declining health status, exposure to communicable diseases, a lack of opportunity, escalating rates of violent trauma and substance abuse, and a lack of access to PHC (Kendall 2008). In some cases, policy decisions can cause health disparities. For example, since the election of a conservative National government in New Zealand in 2008, health targets that had included improving nutrition, physical activity and reducing obesity (MOHNZ 2008) have been refocused to shorter stays in emergency departments and improved access to elective surgery (MOHNZ 2009). This creates a disparity between those with and those without access to health resources and supports.

The major objective of providing equity of access is to eliminate disadvantage, whether it is related to social, economic or environmental factors. Barriers to access include such things as unemployment, lack of education and health literacy, age, gender, functional capacity, and cultural or language difficulties.

The greater the gap between the rich and poor in a country (income inequality) the worse the health status of the whole population in that country.

These factors prevent an individual from developing personal capacity. Barriers to community capacity include geographical features that isolate people from services or opportunities, civil conflict, or a lack of structures and services that support human endeavour.

Inequity of access to health services creates disadvantage. Addressing barriers to access such as unemployment, lack of education or poor health literacy will help eliminate disadvantage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access