Chapter 13 Preterm labour and preterm premature rupture of membranes

PRETERM LABOUR

The World Health Organization (1992) defined preterm birth as delivery before 37 weeks of pregnancy. On the basis of this definition between 6% and 10% of births are preterm (5.6% in Oceania, 5.8% in Europe, 11–12% in America) but around 50% deliveries are more than 35 weeks’ gestation with near 100% survival expected of babies born after 32 weeks of pregnancy. Intact survival exceeds 50% after 27 weeks and improves as gestation increases towards 32 weeks. In this group (27–32 weeks’ fetus) every effort must be made to enhance survival and optimise quality of life.

PRETERM LABOUR: GENERAL STATEMENTS

When preterm labour presents the following considerations are important:

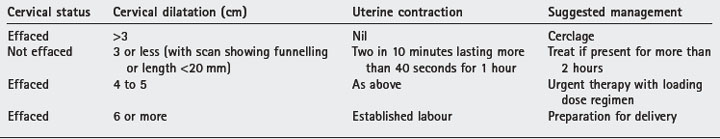

• Detailed pathophysiology of preterm labour is unknown hence the dilemma of effective therapy. Attempts to improve outcome for this obstetric complication (currently some 13 000 000 preterm deliveries worldwide) include efforts to predict or prevent its occurrence by risk scores, sonographic cervical assessment, uterine activity monitoring or tests for presence of fibronectin in cervico-vaginal secretions. Correct diagnosis of onset of labour is important (Table 13.1).

• Obstetric associations include congenital fetal abnormalities, preterm membrane rupture (30–40%), placental separation, intrauterine infection (10–15%)and fetal death. Perform ultrasound scan to exclude contraindications for therapy.

• Only infection and spontaneous onset of uterine activity are amenable to treatment. Past or current history of infection, presence of membrane rupture and stage of cervical dilatation must be considered.

• The most experienced obstetrician on duty should assess all suspected preterm labours. Accurate diagnosis and proper assessment is essential for correct management. Fetal age, numbers, weight and presentation are significant factors governing outcome. If in-house expertise or facilities are not available, consider transfer to a tertiary hospital.

• Obtain detailed obstetric and medical history from the patient. Identify conditions which contraindicate drug therapy or attempts to stop preterm labour or delivery.

• Management of preterm labour, particularly at the extremely preterm periods of gestation, can have significant psychosocial consequences for the parents. There is also clinical risk of mortality and morbidity for the woman from prolonged tocolysis, haemorrhage (more than 1000 ml) thrombosis and sepsis if surgery is performed. Some 6% uterine scars dehisce in future pregnancies after a classical caesarean section.

• Senior neonatologists and obstetricians must counsel parents fully (preferably at a joint meeting) about complications, likelihood of neonatal survival and eventual outcome. Parents must be made aware that expected outcome can change after delivery depending on the baby’s condition at birth, presence of infection, sex of the baby and results of neonatal care such as residue lung disease or intracranial lesions. Respect the parents’ informed choice. They have to live with the consequences.

PRETERM LABOUR AT 23–26 COMPLETED WEEKS

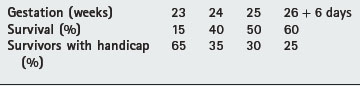

• Between 23 and 24 weeks every extra day increases survival by 3%. From 24 to 26 weeks there is a 2% increase.

• Pregnancy complications leading to delivery at these extremely early gestations do not influence survival before discharge.

• Singleton babies are more likely to survive compared with twins, especially among those between 700 g and 999 g.

• Overall prevalence of moderate or severe cerebral palsy is 1.5–2.5 per 1000 live births. Below 1500 g at birth the incidence is 50 per 1000. Table 13.2 gives examples of survival rates and incidence of major handicaps such as neurodevelopmental deficits with spastic diplegia, hemiplegia, quadriplegia or sensory and intellectual impairment after delivery at extremely early gestations.

• Before 26 completed weeks of gestation there is no evidence to suggest benefit or danger for corticosteroid administration. A full course of corticosteroids (two doses of 12 mg dexamethasone 12 hours apart) for fetuses between 28 and 34 weeks’ gestation reduce mortality, incidence of respiratory distress and intraventricular haemorrhage. Use of thyrotrophin releasing hormone is not recommended. Repeat courses of corticosteroids is also not recommended.

• β-Adrenergic agonists (e.g. ritodrine) are currently not indicated before 23 weeks’ gestation. There is more risk than benefits associated with ritodrine use in twin or high multiple pregnancies between 23 and 26 weeks and 6 days. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2002) does not recommend use of these drugs.

• Neonatal outcome is not improved by prophylactic antibiotic therapy at this early gestation. However, appropriate antibiotics in early pregnancy for pathological colonisation reduce the incidence of preterm birth.

• Before 23 weeks in utero transfer is seldom indicated. Perform caesarean section when there is a maternal indication. Compassionate care only for the baby is acceptable.

• Between 23 and 26 weeks and 6 days, if clinically appropriate, transfer for delivery at a tertiary hospital. Perform caesarean section only after full discussion with the woman and her partner.

• An experienced neonatologist must attend the delivery. The parents’ wishes must be considered regarding neonatal care immediately after delivery. The condition at delivery significantly affects outcome.