1. Preoperative assessment

Melanie Oakley and Joanne Bratchell

CHAPTER CONTENTS

What is preoperative assessment? 3

Aim of preoperative assessment4

Patient information8

Documentation10

Conclusion11

Appendix13

At the end of the chapter the reader should be able to:

• give a definition of preoperative assessment and what is involved

• discuss the three key components of preoperative assessment and how they interface with each other

• detail what is involved in the physiological assessment and the criteria for preoperative investigations

• discuss the psychological component of preoperative assessment

• identify the sociological considerations needed when preoperatively assessing a patient.

Introduction

Nowadays, patients are usually admitted on the day of surgery, not only because financially this is more prudent with increased bed and theatre utilization but also because there are benefits to the patient. These include a reduced risk of hospital-acquired infection due to the reduced length of stay, and an extra night in their own home environment. However, admission on the day of surgery, and, indeed, admission prior to the day of surgery, works most effectively when the patient is adequately prepared some time in advance of the surgical date. Patients may have physical, psychological or social problems that may lead to last minute cancellations or an extended stay if not identified in advance of admission. Some patients do not attend on the day of surgery, or when they do, are told that surgery is no longer necessary. A robust preoperative assessment service will prevent these undesirable outcomes and may help to reduce anxiety in surgical patients at a very stressful time. This chapter will examine preoperative assessment, how it has evolved, and more importantly how it has benefited the patient undergoing anaesthesia and surgery.

What is preoperative assessment?

Preoperative assessment establishes that the patient is fully informed and wishes to undergo the procedure. It ensures that the patient is as fit as possible for the surgery and anaesthetic. It minimises the risk of late cancellations by ensuring that all essential resources and discharge requirements are identified and co-ordinated.

Aim of preoperative assessment

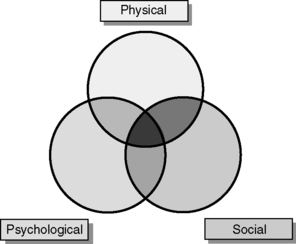

Preoperative assessment aims to minimize patient risk by assessing fitness for surgery, provide information to facilitate informed choice, reduce anxiety about hospital admission and to improve the patient experience. It should take into account the physiological, psychological and social needs of the patient undergoing surgery. Different emphasis may be put on one aspect to the detriment of the other; however, each aspect of preoperative assessment must be given time, because they are of equal importance and are not mutually exclusive (Fig. 1.1). Whilst it is laudable to have a patient who is fit for anaesthesia and surgery from a physical and physiological perspective, care must be taken to ensure that, following their discharge home, they are not expected to resume their role as the primary carer for their partner. Practice Exemplar 1 illustrates that psychological and social aspects of care are just as important as physiological aspects of care, and demonstrates the efficacy of a preoperative assessment (Box 1.1).

|

| Figure 1.1 • Illustration of how the three components of preoperative assessment are inextricably linked: when viewing one, the other two have to be taken into consideration. |

Box 1.1

Box 1.1 Practice exemplar 1

A fit 70-year-old man was admitted to the day surgery unit for bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome repair; he had not been to the preoperative assessment clinic. On admission the nurse admitting him discovered that he was the primary carer for his disabled wife. The operation was explained to him and the degree to which he would be incapacitated following surgery. He agreed that it was going to be a problem but doing the hands one at a time was not an option as leaving his wife for 2 days was a problem. He was adamant about this, and arranging support from the community services rectified the situation. This took time and the operation was delayed until later in the day in order to make sure this was facilitated.

Thus, preoperative assessment should be multifaceted, and when assessing the patient prior to surgery, the following should be aimed for:

• reduction of fears and anxieties by giving a full explanation of the procedure and making sure the patient understands what is going to happen to them

• assessment of the patient’s fitness for the impending anaesthesia and surgery, with interventions as appropriate

• assessment of whether the patient is suitable for day surgery or inpatient surgery

• identification of specialist requirements, e.g. critical care beds

• provision of preoperative instructions

• provision of a contact point

• provision of information about the recovery process postoperatively

• provision of an opportunity for health promotion/patient teaching

• assessment of the patient’s needs post-discharge

• commencement of multidisciplinary preoperative documentation.

Ideally, preoperative assessment should take place following the surgical consultation. Where this is not possible, the assessment should occur sufficiently far in advance of the impending surgery to allow for adequate preoperative optimization. Many patients presenting for surgery have severe health problems, in addition to the problem requiring surgery. It is therefore essential that patients are seen and fully assessed to ensure they are as fit as they can be before surgery. The preassessment clinic should always have a consultant anaesthetist available for patient referrals, but there is no reason why the preoperative clinic should not be nurse-led if they work within agreed protocols and have the appropriate training and experience (Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 2001). Both inpatient and day surgery preoperative assessment clinics within the NHS are nurse-led, with the facility to refer patients with multiple problems to the consultant anaesthetist. Once seen, the patient should be given a date for admission (Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 2001).

Nurse-led preoperative assessment

In day surgery the majority of preoperative assessment is undertaken by trained nurses, and it is this innovation that has led the way for the development of nurse-led inpatient preoperative assessment clinics. Kinley et al (2002) compared the effectiveness of appropriately trained nurses in preoperative assessment with that of pre-registration house officers and found that the nurses were ‘ non-inferior’ to house officers; furthermore, it was found that the house officers ordered considerably more unnecessary tests than the nurses. Rai and Pandit (2003) looked at day surgery cancellations following nurse-led preassessment, and concluded that preassessment had an important role in minimizing cancellations on the day of surgery. Rushforth et al (2006) also concluded that the performance of nurses was equivalent when compared to senior house officers in the identification of co-morbidities or abnormalities of potential perioperative significance. These studies were undertaken by members of the medical profession, who appeared to be surprised with the results. However, Clinch (1997) indicated that nurses achieve quality with preoperative assessment clinics. In addition, a number of studies have also addressed the issue of improved patient satisfaction with nurse-led preoperative assessment clinics (Muldowney, 1993 and Pulliam, 1991).

With the reduction in doctors’ working hours, nurses are well placed to run these clinics and have unique skills that enhance the assessment of the patient prior to surgery. However, this should be a collaborative venture. The anaesthetist is responsible for the patient undergoing anaesthesia and thus should make the final decision as to whether that patient is fit for surgery; therefore, the assessment nurse and the anaesthetist should work in partnership to give the best care to the patient. There should be mutual respect for each other’s abilities and recognition that each will be viewing the assessment interview from different paradigms. Protocols should be put in place to aid the nurse in this venture. Barnes et al (2000) used a computer-based protocol package to assess orthopaedic patients over 65 years of age and found that the assessment carried out by the nurses was thorough and well thought out.

As mentioned previously, preoperative assessment is divided into three areas and each of these will now be examined in more depth.

Physical assessment

The aim of this assessment is to ensure that the patient is fit for anaesthesia and surgery. To ascertain this, the American Society of Anesthesiologist’s (ASA) (1991) fitness for anaesthesia scoring system is utilized (Table 1.1). In day surgery, patients generally have to be ASA 1 or 2, but patients who are ASA 3 can be and are considered. Inpatient preoperative assessment will also utilize this scoring system, but, obviously, being ASA 3 onwards does not exclude the patient from anaesthesia and surgery.

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

| Class 1 | The patient has no organic, physiological, biochemical or psychiatric disturbance. The pathological process for which surgery is to be performed is localized and does not entail systematic disturbance |

| Class 2 | Mild to moderate systematic disturbance caused by either the condition to be treated surgically or by other pathophysiological processes |

| Class 3 | Severe systematic disturbance or disease from whatever cause, even though it may not be possible to define the degree of disability with finality |

| Class 4 | Severe systemic disorders that are already life threatening; not always correctable by operation |

| Class 5 | The moribund patient who has little chance of survival but is submitted to operation in desperation |

| Class 6 | A declared brain-dead patient whose organs are being removed for donor purposes |

All patients having a preoperative assessment will be categorized as to the urgency of their surgery. The categorization system recommended by the NHS Modernisation Agency (2003) is the National Confidential Enquiry into Peri-operative Deaths (NCEPOD) categories (2002) which gives an indication of the time span until surgery (Table 1.2). From the end of December 2008, the minimum expectation of consultant-led elective services is that no one should wait more than 18 weeks from the time they are referred to the start of their hospital treatment, unless it is clinically appropriate to do so or they choose to wait longer (Department of Health, 2008).

| Category | Description | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| NCEPOD 1 | Resuscitation runs concurrent to surgery | Within 1 hour |

| NCEPOD 2 | Resuscitation can be followed by surgery | Within 24 hours |

| NCEPOD 3 | Not life threatening but need early surgery | Within 3 weeks |

| NCEPOD 4 | Surgery at a time to suit the patient and surgeon | To suit patient and surgeon |

In order to assess health status, a comprehensive preoperative assessment questionnaire is completed, often electronically, which will act as a ‘trigger’ for further investigations if required (see Appendix 1, pages 13–15). It is not necessary to routinely carry out investigations on all patients; rather, investigations should only be done where clinically indicated, through either the patient history or physical examination. This means that the patient is not subjected to painful procedures, and also saves time and has considerable financial implications. Investigations are not normally indicated in patients prior to minor surgery who are otherwise healthy. Each hospital should have policies regarding required preoperative investigations (Table 1.3). This may mean that some nurses will need to develop their clinical skills in other areas, e.g. history taking; listening to chest and heart sounds.

| Test | Description |

|---|---|

| ECG | Not normally performed in men under 40 years old and women under 50 years old, but indicated in patients with a cardiac or related history |

| Hb | Only required where the Hb may be low or there may be anticipated significant blood loss during surgery |

| Biochemistry | Only where medical history indicates |

| Chest X-ray | Where indicated in accordance with recommendations from the Royal College of Radiologists (1998) |

Furthermore, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2003) have issued guidance on what investigations to carry out dependent upon the grade of surgery and the ASA status of the patient (Table 1.4). For example, a patient who is graded as ASA 1, having grade 1 surgery, and is over 80 years old will require a 12-lead ECG, whereas the patient who is ASA 1, having grade 1 surgery, and is under 80 years old will require no investigations.

| Grade | Example |

|---|---|

| Grade 1 [Minor] | Drainage of a breast abscess |

| Grade 2 [Intermediate] | Knee arthroscopy |

| Grade 3 [Major] | Total abdominal hysterectomy |

| Grade 4 [Major +] | Total hip replacement |

| Neurosurgery | |

| Cardiovascular surgery |

Whether the patient is an inpatient or a day surgery patient, information must be given to them about fasting prior to surgery, as the majority will be admitted on the day of surgery and they will be already fasting. The guidelines on fasting prior to surgery are clear – 6 hours for solid food; 4 hours for breast milk, and 2 hours for clear non-particulate and non-carbonated fluids (Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 2001 and Royal College of Nursing, 2005). Obviously, if fasting times are exceeded, particularly in the older or younger patient, supplemental intravenous fluids must be considered.

Patients must also be given information regarding the management of long-term medications. For example, patients who are anticoagulated will need advice as to how to safely interrupt their warfarin. As there is no ‘one size fits all’ protocol, this is best done by those managing the patient’s anticoagulation or following a discussion with a haematologist. Other drugs, including antiplatelets and certain types of antidepressants (monoamine oxidase inhibitors), will also need to be stopped for some time prior to surgery. Diabetic patients will need their blood glucose levels (HbA1c) monitored prior to surgery, and advice regarding taking their medications prior to surgery. Increasingly, patients are taking food supplements and herbal remedies, including garlic supplements, Echinacea and St John’s wort. Many of these have an effect on perioperative bleeding or may interact with anaesthetic drugs, and patients must be advised to discontinue them for at least a week preoperatively (Ang-Lee et al., 2001 and Larkin, 2001).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access