CHANGING PARADIGMS OF TREATMENT

Care of the patient with a diagnosis of acute stroke has changed substantially over the past two decades. Prior to the 1990s, stroke was not considered a treatable disease. The care of a patient with stroke used to be supportive in nature, aimed at minimizing complications. With the advent of intravenous (IV) fibrinolysis for the treatment of ischemic stroke, the nature of ischemic stroke treatment shifted dramatically (Jauch et al., 2013). Fibrinolysis offered the first treatment aimed at destroying the offending clot and improving function. However, the treatment was only safe and effective when offered in the first few hours of the ischemic stroke onset. Suddenly, the recognition and rapid transport of a patient with stroke signs and symptoms became paramount and directly linked to both treatment and functional outcome (Jauch et al., 2013).

Since the U.S Food Drug Administration (FDA) approval of IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) to treat ischemic stroke, the delivery of rapid stroke care has continued to evolve. The research guiding rescue therapies such as endovascular treatment of stroke is ongoing and may offer additional time-sensitive interventions to improve stroke outcomes. Endovascular treatment options include intra-arterial treatment of large vessel ischemic stroke with tPA administered directly into a clot using a catheter threaded through the femoral artery (Jauch et al., 2013). Using the intra-arterial approach, mechanical thrombectomy of a large vessel clot is also an option in some stroke centers. Although the science supporting these practices has yielded conflicting outcomes, both therapies are time-sensitive and require rapid recognition and transport to a recognized stroke facility where these treatment options are offered.

The science guiding treatment of ICH and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) also continues to develop and necessitates early symptom recognition and access to treatment. Blood pressure–lowering therapies, reversal of procoagulant therapy, and management of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) are associated with better outcomes in patients with ICH when instituted early and aggressively (Morgenstern et al., 2010). The paradigm of treatment for aSAH has also undergone a transformation, with coil embolization being an option to eliminate a cerebral aneurysm in addition to surgical clipping (Connolly et al., 2012). Most patients with SAH will require a transfer to a stroke center with capabilities to manage endovascular and surgical treatment of the aneurysm and the complex disease process following the hemorrhage. Therefore, the role of organized prehospital care in the chain of stroke survival is essential to both survival and improved outcomes in all types of stroke.

EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICE SYSTEMS

EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICE SYSTEMS

Organized and efficient prehospital health care is a relatively recent concept, developing rapidly after the World Wars and experiencing significant shifts in focus in the past several decades (Simpson, 2013). Organized prehospital care first developed in the 1960s, with improved understanding of the management of trauma associated with automobile accidents (Simpson, 2013). Prior to the 1960s, morticians largely provided transportation to or from the hospital. In 1966, morticians provided more than half of the recorded ambulance services to the hospital. The mortician service consisted solely of transport of injured person without the focus or responsibility to provide rescue medical care for stabilization (Simpson, 2013). The concepts of triage, medical stabilization, and transport of injured persons developed and were refined during the major wars of the 20th century (Goniewicz, 2013). The development of organized trauma care coupled with a national organization of services led to a significant shift in prehospital care. With the Emergency Medical Services Systems Act of 1973 developed by the National Academy of Sciences National Research Council, prehospital care shifted away from a voluntary transport service toward a regional trauma system planning and prehospital emergency care (Simpson, 2013). This shift necessitated an organized system, with a process to call for help and the expectation that the person responding to the call is a trained medical professional. Therefore, the concept of emergency medical staff organization, training, and competency are relatively new professional dimensions that continue to develop.

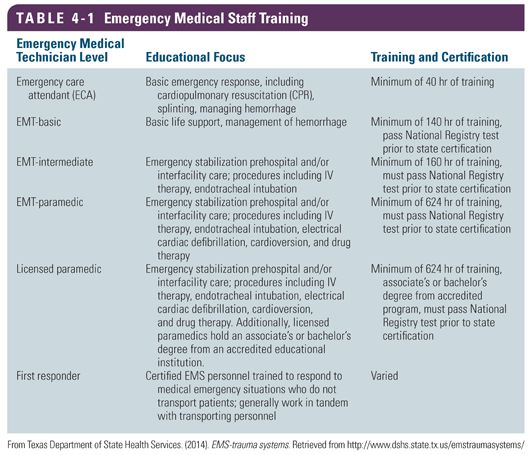

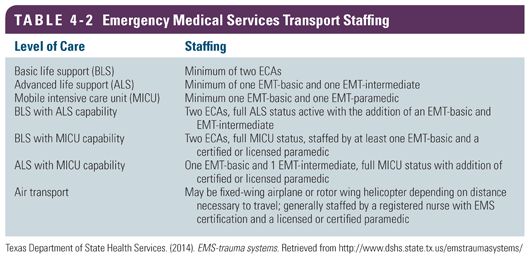

Emergency medical services (EMS) care and transportation are provided by a number of different staff members with different levels of training. EMS transport units consist mainly of ambulances, helicopter, and fixed-wing aircraft. The staff providing care on a ground or air transport may be composed of a mixture of technicians with various levels of expertise and competencies of the nursing staff and the physician staff. Generally, five levels of emergency medical technicians (EMT) are recognized (Table 4-1). The capabilities of an ambulance to care for varying levels of acuity depend on the EMT staffing and level of expertise (Table 4-2). The safe transport of stroke patients to the hospital or between hospitals necessitates that the caregivers in the region understand the distribution of EMT providers and work with the EMS organizations to ensure that proper level EMTs are available to transport patients.

Regional EMS organizations operate within a larger emergency medical service system (EMSS), encompassing the entire spectrum of prehospital care, response to acute illness in the community, intrahospital transport, and coordination of multiple services within a region. As research into the treatment of stroke changed the paradigm of stroke care from support to acute and time-sensitive treatment, the EMSS had to adjust to serve the population. Stroke was no longer a disease for which only supportive care was available; stroke became an acutely treatable disease, highly dependent on early recognition and transport to a facility capable of stroke treatment. In 2004, a task force was convened by the American Heart Association (AHA) and American Stroke Association to determine the barriers to prehospital care of the stroke patient (Acker et al., 2007). In 2007, an expert panel proposed four critical components of an effective stroke system of care. These critical components are as follows:

● For activating and dispatching EMS response for stroke patients, stroke systems should require appropriate processes that ensure rapid access to EMS for acute stroke patients.

● EMSS should use protocols, tools, and training of EMS responders that meet current guidelines for stroke care.

● Prehospital providers, emergency physicians, and stroke experts should collaborate in the development of EMS training, assessment, treatment, and transportation protocols for stroke.

● Patients should be transported to the nearest stroke center for evaluation and care if a stroke center is located within a reasonable transport distance and time.

As the prehospital care of patients with stroke continues to develop, public policy and system planning efforts should focus efforts on improving the system of care in these four essential components of a stroke system of care.

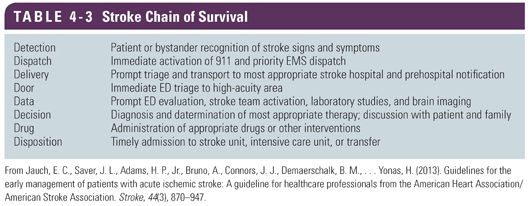

The task force further outlined the scope of an EMSS focused on stroke treatment. A stroke-specific EMSS should include a full spectrum of services including community outreach aimed at educating the public, emergency medical personnel, engagement of public safety agencies including police and fire, emergency departments, as well as critical care units. This definition of EMSS aimed at the treatment of stroke patients fits well with the American Stroke Association’s (ASA) Chain of Survival. The ASA Chain of Survival proposes that the critical steps of stroke care include the detection of symptoms; the dispatch of caregivers with knowledge in stroke detection and early management; the delivery of the patient to a facility with stroke treatment expertise; the experts meeting the stroke patient at the door of the facility; the communication of key patient data relevant to the treatment of stroke; the decision to provide early treatment including IV thrombolysis, if indicated; and the admission of the patient to the hospital or transfer to a higher level of care (Table 4-3). A breakdown in any link of the Chain of Survival could result in poor patient outcomes.

RECOGNITION OF STROKE

RECOGNITION OF STROKE

To facilitate timely transport of a stroke patient to the hospital, the recognition of stroke signs and symptoms is critical. The general public, as well as prehospital providers, must recognize the urgency of seeking treatment when stroke symptoms begin. Delayed time from symptom onset to seeking care is a major barrier to effective treatments in all stroke subtypes. A significant contributor delaying patients from seeking emergent care is the lack of symptom awareness (Crocco, 2007).

A seminal study of stroke system awareness was conducted in 2003. A phone survey of over 61,000 adults spanning 17 states was conducted by the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) assessing knowledge of stroke signs and symptoms. Study findings indicated that less than 20% of respondents could identify all signs and symptoms of stroke and possessed the knowledge of when to call 911 (Greenlund et al., 2003). Additionally, few recognized that stroke symptoms indicated a medical emergency necessitating rapid transport to the hospital. Recognition of symptoms and necessary action was significantly less common in ethnic minorities, those of older and younger age, those reporting less education, and respondents who smoked. The findings have been replicated in multiple regional and national surveys with similar findings.

Patients who experience an acute stroke continue to struggle with stroke symptom awareness in the months and years after their stroke event. Despite experiencing a stroke, many stroke survivors continue to have difficulty articulating the signs and symptoms of stroke and the need to rapidly mobilize to the emergency department. Therefore, community education and awareness is a significant priority for hospitals with organized stroke programs. Educational initiatives aimed at the general public as well as patients who have survived a stroke and are at risk of another stroke event must focus on both the signs and symptoms associated with stroke as well as the urgency with which a victim should seek medical care (Crocco, 2007). Target audiences for stroke education and outreach include populations at risk for stroke, the general public, as well as large employers (Rymer, 2005).

The ideal vehicle for public education remains a matter of continued debate. Certified stroke centers are required to provide community outreach education to maintain certification. However, data are unclear regarding the efficacy of such education. Generally, large media outreach campaigns are thought to be superior in reaching the public. Yet, studies show that even large media campaigns are not always effective. A recent systematic review of 10 media outreach campaigns designed to educate the public on stroke revealed mixed results. Media campaigns to educate the public were found to increase public awareness of signs and symptoms of stroke, without impacting public awareness of the need for emergency response to the symptoms (Lecouturier et al., 2010

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree