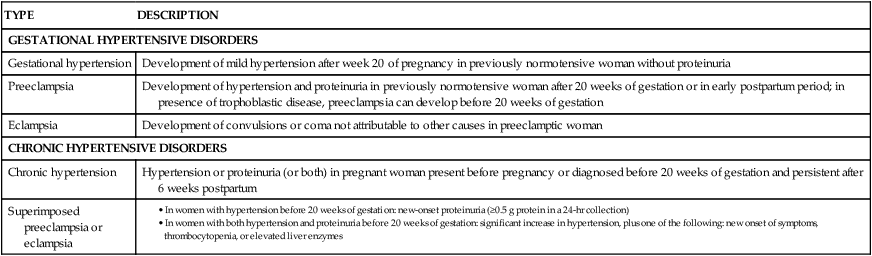

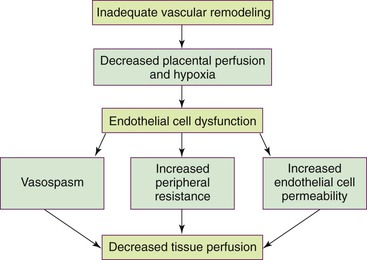

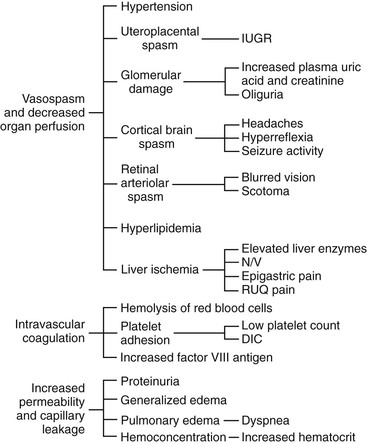

• Differentiate the defining characteristics of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and eclampsia, and chronic hypertension. • Describe the pathophysiologic mechanisms of preeclampsia and eclampsia. • Discuss the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum management of the woman with mild or severe gestational hypertension. • Discuss the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum management of the woman with mild or severe preeclampsia. • Discuss the preconception, antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum management of the woman with chronic hypertension. • Identify the priorities for the management of eclamptic seizures. • Explain the effects of hyperemesis gravidarum on maternal and fetal well-being. • Discuss the management of the woman with hyperemesis gravidarum in the hospital and at home. • Differentiate among the causes, signs and symptoms, possible complications, and management of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, premature dilation of the cervix, and hydatidiform mole. • Compare and contrast placenta previa and abruptio placentae in relation to signs and symptoms, complications, and management. • Discuss the diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. • Differentiate signs and symptoms, effects on pregnancy and the fetus, and management during pregnancy of common sexually transmitted infections and other infections. • Explain the basic principles of care for a pregnant woman undergoing abdominal surgery. • Discuss implications of trauma on the mother and fetus during pregnancy. • Identify the priorities in assessment and stabilization measures for the pregnant trauma victim. • Explain how performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation on a pregnant woman differs from performing this procedure on other adults. Additional related content can be found on the companion website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/Maternity/ • Critical Thinking Exercise: Preeclampsia • Nursing Care Plan: Hyperemesis Gravidarum • Nursing Care Plan: Mild Preeclampsia: Home Care • Nursing Care Plan: Placenta Previa • Nursing Care Plan: Severe Preeclampsia: Hospital Care • Spanish Guidelines: Assessment of Bleeding in Early Pregnancy Hypertensive disorders are the most common medical complication of pregnancy, occurring in 5% to 10% of all pregnancies. The incidence varies among hospitals, regions, and countries. Hypertensive disorders are a major cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide (Sibai, 2007). The four most common types of hypertensive disorders occurring in pregnancy are (1) gestational hypertension, (2) preeclampsia, (3) chronic hypertension, and (4) preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension (Gilbert, 2007). The classification of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy is confusing because standard definitions are not consistently used by all health care providers. The classification system most commonly used in the United States today is based on reports from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (2002) and the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy (Working Group) (2000). This classification system is summarized in Table 21-1. TABLE 21-1 Classification of Hypertensive States of Pregnancy • In women with hypertension before 20 weeks of gestation: new-onset proteinuria (≥0.5 g protein in a 24-hr collection) • In women with both hypertension and proteinuria before 20 weeks of gestation: significant increase in hypertension, plus one of the following: new onset of symptoms, thrombocytopenia, or elevated liver enzymes Sources: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). (2002). Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 33. Washington DC: ACOG; Sibai, B. M. (2007). Hypertension. In S. Gabbe, J. Niebyl, & J. Simpson (Eds.), Obstetrics: Normal and problem pregnancies (5th ed.) Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone. Gestational hypertension is the onset of hypertension without proteinuria after week 20 of pregnancy (ACOG, 2002; Working Group, 2000). Hypertension is defined as a systolic blood pressure (BP) greater than 140 mm Hg or a diastolic BP greater than 90 mm Hg. The hypertension should be recorded on at least two separate occasions at least 4 to 6 hours apart but within a maximum of a 1-week period (ACOG, 2002; Sibai, 2007; Working Group, 2000). Both the Working Group and the American Heart Association (AHA) have published extensive recommendations for accurately measuring BP (Pickering et al., 2005; Working Group, 2000). Box 21-1 provides detailed instructions for measuring BP. Gestational hypertension is the most frequent cause of hypertension during pregnancy, with an incidence of 6% to 17% in primigravidas and 2% to 4% in multiparous women. It occurs much more frequently in women with multifetal pregnancies than in other women (Sibai, 2007). Gestational hypertension usually develops at or after 37 weeks of gestation. Women with gestational hypertension have no evidence of preexisting hypertension, and their BPs return to normal levels within 6 weeks after giving birth. Women with mild gestational hypertension usually have good pregnancy outcomes. Some women who are initially thought to have gestational hypertension will eventually be diagnosed with chronic hypertension instead. Others will go on to develop proteinuria, thereby changing their diagnosis to preeclampsia. Women who are diagnosed with gestational hypertension before 35 weeks of gestation are more likely to progress to preeclampsia than women whose onset of hypertension occurs closer to term (Sibai). Preeclampsia is a pregnancy-specific condition in which hypertension and proteinuria develop after 20 weeks of gestation in a previously normotensive woman. A significant contributor to maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, preeclampsia complicates approximately 3% to 7% of all pregnancies (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] & ACOG, 2007). Preeclampsia is a vasospastic, systemic disorder and is usually categorized as mild or severe for purposes of management (ACOG, 2002; Working Group, 2000). Table 21-2 lists criteria for mild and severe preeclampsia, and Table 21-3 gives common laboratory changes that occur in mild and severe preeclampsia. TABLE 21-2 Differentiation between Mild and Severe Preeclampsia FHR, Fetal heart rate; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction. Sources: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). (2002). Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 33. Washington, DC: ACOG; Sibai, B. M. (2007). Hypertension. In S. Gabbe, J. Niebyl, & J. Simpson (Eds.), Obstetrics: Normal and problem pregnancies (5th ed.) Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone. TABLE 21-3 Common Laboratory Changes in Preeclampsia *LDH values differ according to the test or assays being performed. Sources: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). (2002). Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 33. Washington, DC: ACOG; Cunningham, F., Leveno, K., Bloom, S., Hauth, J., Gilstrap, L., & Wenstrom, K. (Eds.). (2005). Williams obstetrics (22nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill; Dildy, G. (2004). Complications of preeclampsia. In G. Dildy, M. Belfort, G. Saade, J. Phelan, G. Hankins, & S. Clark (Eds.), Critical care obstetrics (4th ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; Sibai, B. M. (2007). Hypertension. In S. Gabbe, J. Niebyl, & J. Simpson (Eds.), Obstetrics: Normal and problem pregnancies (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone. Proteinuria is defined as a concentration at or above 30 mg/dl (≥1+ on dipstick measurement) or more in at least two random urine specimens collected at least 6 hours apart with no evidence of urinary tract infection. In a 24-hour specimen, proteinuria is defined as a concentration at or above 300 mg/24 hours. Because of the discrepancy between random protein determinations the diagnosis of proteinuria should be based on a 24-hour urine collection if possible or a timed collection corrected for creatinine excretion if a 24-hour specimen is not feasible (ACOG, 2002; Longo, Dola, & Pridjian, 2003). To ensure accurate results, proteinuria should be determined using only a urine specimen that has been collected either by catheterization or by a thorough clean-catch technique. Eclampsia is the onset of seizure activity or coma in a woman with preeclampsia but with no history of a preexisting abnormality that can result in seizure activity (ACOG, 2002). The initial presentation of eclampsia varies, with one third of the women developing eclampsia during the pregnancy, one third during labor, and one third within 72 hours postpartum (Emery, 2005). Chronic hypertension is defined as hypertension that occurs before the pregnancy or is diagnosed before the twentieth week of gestation. Hypertension initially diagnosed during pregnancy that persists longer than 6 weeks postpartum is also classified as chronic hypertension (Sibai, 2007). Other authorities believe that a diagnosis of chronic hypertension can be made only if the BP has not returned to normal levels by 12 weeks after birth (Roberts & Funai, 2009). Women with chronic hypertension may develop superimposed preeclampsia, which increases the morbidity for both the mother and the fetus. A diagnosis of superimposed preeclampsia is made with the following findings (Sibai, 2007): Preeclampsia is a condition unique to human pregnancy; signs and symptoms develop only during pregnancy and disappear quickly after birth of the fetus and placenta. The cause of preeclampsia is not known. Although preeclampsia is generally a disease of primigravidas, its cause may not be the same for all women. For example, the pathogenesis for a healthy nulliparous woman who develops mild preeclampsia near term or in labor may be very different than that of the woman who has preexisting vascular disease or diabetes, a multifetal pregnancy, or who develops severe preeclampsia earlier in the pregnancy (Sibai, 2007). Box 21-2 lists risk factors for the development of preeclampsia. Many theories have been suggested to explain the cause of preeclampsia. Current theories that are still being considered include abnormal trophoblast invasion, coagulation abnormalities, vascular endothelial damage, cardiovascular maladaptation, and dietary deficiencies or excesses. Immunologic factors and genetic predisposition may also play an important role (Sibai, 2007). Preeclampsia can progress along a continuum from mild to severe preeclampsia to eclampsia. Current thought is that the pathologic changes that occur in the woman with preeclampsia are caused by disruptions in placental perfusion and endothelial cell dysfunction (Gilbert, 2007; Peters, 2008). These pathologic changes are present long before the clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia is made (Roberts & Funai, 2009). Normally in pregnancy the spiral arteries in the uterus widen from thick-walled muscular vessels to thinner, saclike vessels with much larger diameters. This change increases the capacity of the vessels, allowing them to handle the increased blood volume of pregnancy. Because this vascular remodeling does not occur or only partially develops in women with preeclampsia, decreased placental perfusion and hypoxia result (Peters). Placental ischemia is thought to cause endothelial cell dysfunction by stimulating the release of a substance that is toxic to endothelial cells. This anomaly causes generalized vasospasm, which results in poor tissue perfusion in all organ systems, increased peripheral resistance and BP, and increased endothelial cell permeability, leading to intravascular protein and fluid loss and ultimately to less plasma volume. The main pathogenic factor is not an increase in BP but poor perfusion as a result of vasospasm and reduced plasma volume (Fig. 21-1) (Gilbert; Peters; Roberts & Funai). Fig. 21-2 demonstrates how endothelial cell dysfunction causes many of the common signs and symptoms of preeclampsia. Reduced kidney perfusion decreases the glomerular filtration rate and leads to degenerative glomerular changes and possibly oliguria. Pathologic changes in the endothelial cells of the glomeruli (glomerular endotheliosis) are uniquely characteristic of preeclampsia. Protein, primarily albumin, is lost in the urine. Uric acid clearance is decreased. Serum uric acid levels, however, increase. Sodium and water are retained. Acute tubular necrosis and renal failure may occur (Gilbert, 2007; Peters, 2008; Roberts & Funai, 2009). Plasma colloid osmotic pressure decreases as serum albumin levels decrease. Intravascular volume is reduced as fluid moves out of the intravascular compartment, resulting in hemoconcentration, increased blood viscosity, and tissue edema. The hematocrit value increases as fluid leaves the intravascular space. In severe preeclampsia, blood volume may decrease to or below nonpregnancy levels; severe edema develops, and rapid weight gain is seen. Arteriolar vasospasm can cause endothelial damage and contribute to an increased capillary permeability, which increases edema and further decreases intravascular volume, predisposing the woman with preeclampsia to pulmonary edema (see Fig. 21-2) (Gilbert, 2007; Roberts & Funai, 2009). Decreased liver perfusion results in impaired liver function. Liver enzyme levels increase in the wake of liver damage. If hepatic edema and subcapsular hemorrhage develop, the woman may complain of epigastric or right upper quadrant pain. Rupture of a subcapsular hematoma is a life-threatening complication and a surgical emergency (Gilbert, 2007) (see Fig. 21-2). Arteriolar vasospasms and decreased blood flow to the retina lead to visual symptoms such as scotomata (blind spots) and blurring. Neurologic complications associated with preeclampsia include cerebral edema and hemorrhages and increased central nervous system (CNS) irritability, the last of which causes headache, hyperreflexia, positive ankle clonus, and seizures (Gilbert, 2007; Longo et al., 2003; Roberts & Funai, 2009) (see Fig. 21-2). Preeclampsia contributes significantly to restriction of fetal growth and the incidence of placental abruption (Hull & Resnik, 2009; Peters, 2008). Impaired placental perfusion leads to early degenerative aging of the placenta. The rate of fetal complications is directly related to the severity of the disease (Longo et al., 2003). HELLP syndrome is a laboratory diagnosis for a variant of severe preeclampsia that involves hepatic dysfunction, characterized by hemolysis (H), elevated liver enzymes (EL), and low platelets (LP), not a separate illness. No consensus has been reached, however, regarding which laboratory tests should be used to diagnose HELLP syndrome or what values should be considered abnormal (Sibai, 2007). Table 21-3 lists laboratory changes that occur in HELLP syndrome. A unique form of coagulopathy occurs with HELLP syndrome. The platelet count is low, but coagulation factor assays, prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and bleeding time remain normal. In some instances, hemolysis does not occur, and the condition is termed ELLP or partial HELLP syndrome (Sibai, Dekker, & Kupferminc, 2005). Because no agreement has been reached on diagnostic criteria for HELLP syndrome, its reported incidence varies. It has been reported to occur in anywhere from 5% to 20% of women with preeclampsia (Emery, 2005; Gilbert, 2007). HELLP syndrome appears to occur more frequently in Caucasian women than in women of other races. A diagnosis of HELLP syndrome is associated with an increased risk for adverse perinatal outcomes, including pulmonary edema, acute renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), placental abruption, liver hemorrhage or failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, and stroke (Sibai, 2007). The syndrome is associated with an increased risk of maternal death. Perinatal mortality rates range from 7.4% to 20.4%, with a maternal mortality of approximately 1% (Sibai). The rate of preterm birth in women with HELLP syndrome is approximately 70%, with 15% of these occurring before 28 weeks of gestation. Most of the perinatal deaths occur before 28 weeks of gestation, in association with placental abruption or severe intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (Sibai). HELLP syndrome is often nonspecific in clinical presentation. A majority of patients report a history of malaise for several days and some have a nonspecific viral-like syndrome. Many women (30%-90%) experience epigastric or right upper quadrant abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Headaches are reported by 33% to 61% of all women with the syndrome. A small number of women may exhibit symptoms related to thrombocytopenia, such as bruising or hematuria (Sibai, 2007). Numerous clinical trials have been conducted studying various methods for preventing preeclampsia. These interventions included the use of low-dose aspirin, antioxidants, calcium, magnesium, and zinc; restricted protein or sodium intake; and fish oil supplementation. None of the interventions demonstrated a significant benefit in preventing or reducing the severity of preeclampsia (Sibai, 2007). No reliable test has been developed that can be used as a routine screening tool for predicting preeclampsia. Research findings reported by Cockey (2005) suggested that women were increasingly likely to develop preeclampsia if they had low levels of placental growth factor (PIGF) in their urine. The low levels of PIGF were apparent beginning at weeks 25 through 28 of pregnancy. This finding sets the stage for the development of a screening tool for women who are at high risk for preeclampsia (Cockey).

Pregnancy at Risk

Gestational Conditions

Web Resources

![]()

Hypertension in Pregnancy

Significance and Incidence

Classification

TYPE

DESCRIPTION

GESTATIONAL HYPERTENSIVE DISORDERS

Gestational hypertension

Development of mild hypertension after week 20 of pregnancy in previously normotensive woman without proteinuria

Preeclampsia

Development of hypertension and proteinuria in previously normotensive woman after 20 weeks of gestation or in early postpartum period; in presence of trophoblastic disease, preeclampsia can develop before 20 weeks of gestation

Eclampsia

Development of convulsions or coma not attributable to other causes in preeclamptic woman

CHRONIC HYPERTENSIVE DISORDERS

Chronic hypertension

Hypertension or proteinuria (or both) in pregnant woman present before pregnancy or diagnosed before 20 weeks of gestation and persistent after 6 weeks postpartum

Superimposed preeclampsia or eclampsia

Gestational hypertension

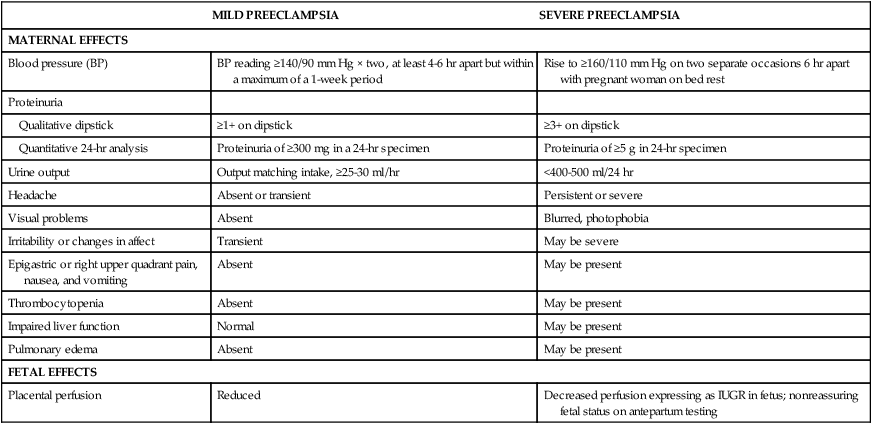

Preeclampsia

MILD PREECLAMPSIA

SEVERE PREECLAMPSIA

MATERNAL EFFECTS

Blood pressure (BP)

BP reading ≥140/90 mm Hg × two, at least 4-6 hr apart but within a maximum of a 1-week period

Rise to ≥160/110 mm Hg on two separate occasions 6 hr apart with pregnant woman on bed rest

Proteinuria

Qualitative dipstick

≥1+ on dipstick

≥3+ on dipstick

Quantitative 24-hr analysis

Proteinuria of ≥300 mg in a 24-hr specimen

Proteinuria of ≥5 g in 24-hr specimen

Urine output

Output matching intake, ≥25-30 ml/hr

<400-500 ml/24 hr

Headache

Absent or transient

Persistent or severe

Visual problems

Absent

Blurred, photophobia

Irritability or changes in affect

Transient

May be severe

Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting

Absent

May be present

Thrombocytopenia

Absent

May be present

Impaired liver function

Normal

May be present

Pulmonary edema

Absent

May be present

FETAL EFFECTS

Placental perfusion

Reduced

Decreased perfusion expressing as IUGR in fetus; nonreassuring fetal status on antepartum testing

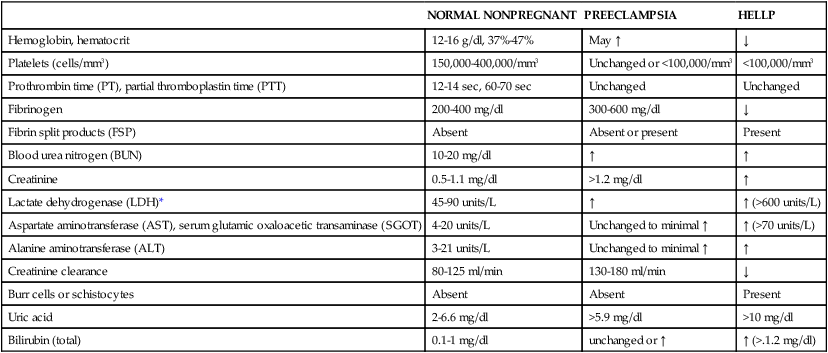

NORMAL NONPREGNANT

PREECLAMPSIA

HELLP

Hemoglobin, hematocrit

12-16 g/dl, 37%-47%

May ↑

↓

Platelets (cells/mm3)

150,000-400,000/mm3

Unchanged or <100,000/mm3

<100,000/mm3

Prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT)

12-14 sec, 60-70 sec

Unchanged

Unchanged

Fibrinogen

200-400 mg/dl

300-600 mg/dl

↓

Fibrin split products (FSP)

Absent

Absent or present

Present

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

10-20 mg/dl

↑

↑

Creatinine

0.5-1.1 mg/dl

>1.2 mg/dl

↑

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)*

45-90 units/L

↑

↑ (>600 units/L)

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT)

4-20 units/L

Unchanged to minimal ↑

↑ (>70 units/L)

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

3-21 units/L

Unchanged to minimal ↑

↑

Creatinine clearance

80-125 ml/min

130-180 ml/min

↓

Burr cells or schistocytes

Absent

Absent

Present

Uric acid

2-6.6 mg/dl

>5.9 mg/dl

>10 mg/dl

Bilirubin (total)

0.1-1 mg/dl

unchanged or ↑

↑ (>.1.2 mg/dl)

Eclampsia

Chronic hypertension

Chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia

Preeclampsia

Etiology

Pathophysiology

HELLP Syndrome

Care Management

Identifying and preventing preeclampsia

Pregnancy at Risk: Gestational Conditions

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

times the length of the upper arm).

times the length of the upper arm).