Chapter 2 Preadmission and preoperative patient care

Introduction

Preoperative care encompasses the unique holistic physical, psychological, emotional and spiritual preparation of patients prior to their surgery. Adequate preoperative preparation can lead to optimal outcomes for the surgical patient. Preoperative care is a complex and dynamic field; however, much of the literature and clinical guidelines lacks evidence. This leaves room for debate on what constitutes optimal patient care (Solca, 2006). The perioperative nurse plays a critical role with patient assessment, preparation, management and evaluation of care.

Preadmission

The preadmission stage of a patient’s surgical journey is critical in the preparation of the patient for surgery. The requirement to increase the number of patients receiving surgery (maximising theatre utilisation) and reduce waiting lists and waiting times has determined the need for patients to be fully prepared, thus minimising the risk of cancellations or delays (Beck, 2007). The need for increased efficiency has been driven largely by government and policy, such as the New Zealand Health Strategy (Hodgson, 2006) and those developed by the Australian Department of Health and Ageing (2007). The effectiveness of preadmission clinics is demonstrated in an associated reduction in cancellation of cases, shortened length of hospital stay related to increased patient well-being and improved patient satisfaction (Correll et al., 2006; Ferschl et al., 2005; Halaszynski et al., 2004). The preassessment clinic plays an important role in minimising cancellations by having the patient appropriately assessed, investigated and prepared for the surgery (Rai & Pandit, 2003).

Preoperative assessment

Preoperative assessment is the clinical investigation that precedes anaesthesia for surgical or non-surgical procedures and which provides data for the selection of an appropriate anaesthetic strategy (van Klei et al., 2004). Preoperative assessment may be required for surgery that takes place in a variety of practice settings, including, hospitals, clinics, doctors’ rooms and dentists’ rooms, both in the public and private settings.

Traditionally, patients were visited on the wards by the anaesthetist the day before surgery. However, if significant comorbidities were present, this could result in cancellation of surgery. A late cancellation is distressing for the patient and results in under-utilisation of the operating room as it may not be possible to schedule another patient (Van Klei et al., 2002). The provision of preoperative/preadmission clinics has enabled an opportunity to manage comorbidities, provide quality safe perioperative care and reduce cancellations. Box 2-1 outlines the objectives of preoperative assessment.

Box 2-1 Preoperative assessment objectives

The principles of assessment vary and include ensuring that the consultation occurs at an appropriate time and place. The environment should provide adequate privacy for the patient, such as a single-bed consulting room, and the consultation should occur without interruption. Ideally, the consultation should occur several weeks before surgery. This is particularly important if there are significant comorbidities requiring management, special laboratory tests or procedures to be ordered, or planning/management of any anaesthetic concerns, and to allow time for patient education (Barnett, 2005; Garcia-Miguel et al., 2003). Each patient is unique and requires the opportunity to express concerns, ask questions and be supported in their decision-making, even if that means changing their minds as to the intended surgical procedure.

The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists acknowledges that it is not always possible to plan early consultation and assessment of patients, particularly in cases of emergency; however, it stresses that the consultation must not be modified except when the overall welfare of the patient is at risk (ANZCA, 2003). It also recommends that the assessment of patients prior to anaesthesia is the primary responsibility of the anaesthetist and, where practical, is to be conducted by the anaesthetist who is to perform the anaesthesia (ANZCA, 2003). This differs from Europe and the United States, where nurse anaesthetists or anaesthetic non-physician practitioners may also take part in the preoperative assessment and provide anaesthetic services to patients under the direct supervision of a consultant anaesthesiologist. Wilkinson (2007, p 168) describes the non-physician practitioner role requirement to:

However, nurse-led clinics are developing and provide competent preoperative assessments of patients. A study by Kinley et al. (2003) concluded that preoperative assessments by qualified nurses were equal in quality to assessment by pre-registration medical residents. Further discussion on nurse-led clinics is given below.

A number of different health care professionals may be involved in the care and preparation of the patient prior to surgery; for example, preadmission nurse, anaesthetist, dietician, physiotherapist, pharmacist, social worker or occupational therapist. Assessment involves a two-way preadmission interview between the patient and health practitioner so that the patient is assessed physically, psychologically and socially for surgery (Walsgrove, 2006). The preadmission interview is scheduled once the patient returns a completed medical/health questionnaire, and provides the opportunity for information sharing and for education to occur.

Nurse-led clinics

Preadmission clinics may be staffed by nurses whose role includes patient preoperative screening. This may detect medical or physical conditions that may generate a referral to the surgeon or anaesthetist, as discussed above (Finegan et al., 2005). Within nurse-led clinics, policies and protocols provide guidance as to when referral may be made to others within the multidisciplinary health care team. Nurse-led clinics may prevent inappropriate admission of unfit patients and reduce late cancellations (Hilditch et al., 2003; Kinley et al., 2003).

The responsibilities and activities of the preadmission nurse may vary between different health care agencies. A major responsibility is to ensure that patients are available and prepared for their allocated surgery. This includes communicating with patients by telephone regarding preoperative diagnostic tests, organisation of the preoperative assessment consultation and detailed patient education so that the patient is prepared for the planned surgery. A study by van Klei et al. (2002) demonstrated that the preadmission nurse can undertake the patient’s health assessment independently, provided the anaesthetist is available to perform additional assessment for patients who are categorised as requiring further assessment.

To be effective, this advanced role requires clinical nurse specialists to be educated to a Master’s level, with skills and knowledge in anatomy, clinical assessment and decision-making (Ormrod & Casey, 2004). Some authors argue that the role is not one of a nurse specialist but rather that of an advanced Nurse Practitioner. The Nurse Practitioner has similar educational qualifications; however, the scope of practice in a speciality field is generally broader (Barnett, 2005). Nurse Practitioners must be able to collect, identify and interpret important information. They provide preoperative information and education, order and review diagnostic test results, perform physical examinations and take medical histories independently, and work collaboratively with other health care providers, such as anaesthetists (Barnett, 2005).

Even though most preoperative assessments are carried out in clinics, some aspects are completed over the telephone. Trials in Britain have demonstrated success in telephone assessment of patients, with the result that more patients can be assessed in a timely manner (Digner, 2007). Strict selection criteria are required to identify patients who are suitable to be assessed via telephone. Suggested criteria include:

The format, policy and protocol of the telephone assessment should be the same as for face-to-face assessment. Consent must also be obtained for telephone assessment, and identification of the correct patient confirmed using unique patient identifiers, such as mother’s maiden name or date of birth.

The types of questions asked during consultation may vary and Table 2-1 provides some examples of preoperative questions. Following consultation, a written summary is included in the patient’s health record.

Table 2-1 Preoperative assessment questions

| Preoperative assessment questions | Rationale |

| History | |

| Knowledge of problems with a previous anaesthetic enables the anaesthetist to prepare for such problems. | |

| 3. Have you or any member of your family had any problems with an anaesthetic? | This may be indicative that the patient may have the same problem. |

| 4. Have you had any previous surgery? | Provides a baseline for education. |

| 5. Do you ever get any chest pain or shortness of breath? | May require the patient to undergo diagnostic tests prior to surgery. |

| Taking of illicit drugs and/or excessive alcohol intake may necessitate increased amounts of anaesthetic agents. | |

| 8. Do you smoke? If so how much, how often? | Smoking effects on pulmonary function. |

| Will affect choice of medications given. | |

| Certain medications, including herbal and complementary therapies, may have consequences for the anaesthetic or surgical procedure. | |

| 13. Do you have any medical problems? | Certain comorbidities require specific preparation before surgery. Prior history may indicate potential medical problems or undiagnosed diseases. |

| Physical | |

| 1. Do you have any dentures or loose teeth, caps or crowns? | Necessary knowledge for induction of anaesthesia and intubation. |

| Provides data for body mass index (BMI) calculation for anaesthetic. | |

| Psychosocial | |

| 1. Do you have any cultural beliefs that we should be particularly aware of, such as Jehovah’s witness? | Ensures cultural safety is observed. |

| 2. Do you have any questions or would you like me to discuss any aspect of the anaesthetic? | Alleviates/minimises anxieties and fears. |

| 3. Is there anything else your surgeon or anaesthetist should know? | Provides opportunity to identify outstanding issues or concerns. |

Adapted from Solca (2006)

The American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) physical status classification system is commonly used to assist in preoperative assessment of patients (Table 2-2). Devised in 1941, the system was meant to assess the degree of sickness or the physical state of a patient prior to selecting the anaesthetic or prior to performing surgery. It is not a tool to be used to determine or measure operative risk (ASA, 2002).

Table 2-2 ASA physical status classification system

| ASA category | Preoperative health status | Comments/examples |

| ASA 1 | A normal healthy patient | Patient able to walk up one flight of stairs without distress. Little or no anxiety. Little or no risk. |

| ASA 2 | A patient with mild disease | Patient able to walk up one flight of stairs but will need to stop after completion of exercise due to distress. History of well-controlled disease states, including non-insulin-dependent diabetes, pre-hypertension, epilepsy, asthma or thyroid conditions |

| ASA 3 | A patient with severe systemic disease | Patients able to walk up one flight of stairs but will have to stop en route because of distress. History of angina pectoris, myocardial infarction (MI), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), heart failure (HF) over 6 months ago. |

| ASA 4 | A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | Patient unable to walk up one flight of stairs. History of unstable angina pectoris, MI, CVA, HF within last 6 months. |

| ASA 5 | A moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the operation | Generally, hospitalised, terminally ill patients. |

| ASA 6 | A declared brain dead patient whose organs are being removed for donor purposes | – |

American Society of Anesthesiologists (2007)

While preoperative assessment cannot claim to be the answer to all of the potential problems faced by elective surgical patients, it is vital that health care professionals involved in patient care prepare and coordinate their efforts to ensure the best possible outcome for the patient. Box 2-2 highlights the importance of assessment before admission for surgery.

Preoperative investigations

In the past, all patients received standard testing regardless of their physical condition. Tests that were directly, indirectly or even remotely related to the planned surgery were ordered. While the tests proved useful as baseline values for those caring postoperatively for the patient, in the current era of cost containment, such testing is not financially practical (Halaszynski et al., 2004). Furthermore, current evidence supports the view that change in patient management rarely occurs as a result of routine testing (Bryson et al., 2006; Johnson & Mortimer, 2002).

Evidence-based guidelines have been developed which rationalise the use of preoperative tests, leading to a reduction of tests ordered with no compromise to patient safety occurring, and the added benefit of reducing costs to both the patient and the health care system (Ferrando et al., 2005; Finegan et al., 2005; Johnson & Mortimer, 2002). Even in patients who are older than 70 years, routine preoperative testing has been shown to be of little benefit (Bryson et al., 2006). Although some authors suggest that routine testing can be completely eliminated, others propose that testing should be based on the patient’s medical condition (Yaun et al., 2005). Each health care institution should develop policies and procedures regarding preoperative assessment and screening.

Medical history

A complete medical history of the individual is required. This includes details of past surgical history, family medical history and current intake of medication. Social history must also be examined, noting alcohol intake, smoking habits, use of illicit drugs and use of non-prescription medications and/or complementary medications. Also noted are the support systems available to the patient following surgery, such as family, church or other community groups (van Klei et al., 2004).

Chest X-rays

The benefit of chest X-ray examinations as part of the preoperative examination is unproven; even when abnormalities are detected the information is not necessarily useful. Furthermore, routine chest X-rays are ineffective in detecting asymptomatic tuberculosis or cancer. Therefore, a preoperative chest X-ray is not recommended in asymptomatic patients, regardless of age (Finegan et al., 2005; Joo et al., 2005).

Electrocardiography

The ordering of a routine 12-lead ECG has been common practice for all adult patients before an operation involving regional or general anaesthesia but there is growing consensus that it is of little benefit and only needed for a subset of patients with cardiac signs and older patients (Ho, 2007). Commonly, an ECG is not routinely needed for asymptomatic males younger than 45 years and females younger than 50 years, and should be based on the clinical needs of the patient. Abnormalities on preoperative ECGs in older patients are common but are of limited value in predicting postoperative cardiac complications (Lui et al., 2002).

Obtaining preoperative ECGs based on an age cut-off alone may not be indicated because ECG abnormalities in older people are prevalent but non-specific and less useful than the presence and severity of comorbidities in predicting postoperative cardiac complications. However, in the elderly, silent myocardial infarction is not uncommon and the availability of a baseline ECG is helpful in the subsequent diagnosis and management of any suspected cardiac event (Finegan et al., 2005; Yuan et al., 2005).

Blood investigations

Traditionally, routine blood tests prior to surgery have been carried out for all patients. This has included a full blood count (FBC), urea, electrolytes and glucose. This practice was expensive for individuals and health care institutions, and offered little advantage to the patient. A study by Johnson and Mortimer (2002) found that, commonly, results were not in the patient’s notes on arrival at the operating room and, when abnormalities were detected, there was little change in patient management.

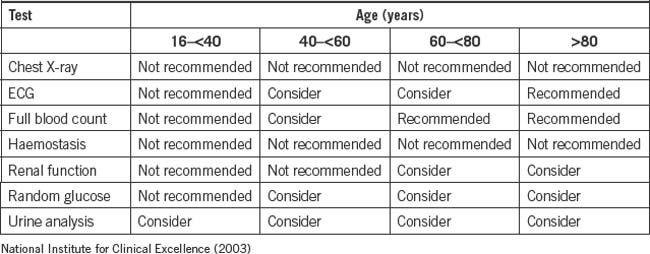

To ensure appropriate ordering of tests, it is recommended that a detailed history and physical examination is performed. For major surgery, a blood group test and screen will also be required to ensure the availability of blood should a transfusion be required. Informed consent is required from patients for authorisation of a blood transfusion prior to a surgical procedure. Documentation of such is recorded in the patient’s health record and/or on the surgical Consent/Agreement to Treatment form. Table 2-3 lists the tests recommended by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence.

Smoking

An assessment of patient smoking habits is ascertained well before surgery and is undertaken by the primary person making the surgical referral. Smoking is a risk factor for postoperative wound dehiscence, wound infections and delayed healing (Warner, 2005b). Smoking also results in a higher incidence of perioperative respiratory and cardiovascular complications compared to non-smoking (Kuri et al., 2005; Warner, 2005a). The optimum length of time a smoker should cease smoking prior to surgery remains unclear; times range from 12 hours to several weeks, with all such cessation showing improvement in, for example, rates of postoperative wound healing (Kuri et al., 2005; Warner 2005a, 2005b). However, there is no absolute evidence that cessation of smoking before surgery reduces complications (Box 2-3).

Opportunity may be taken by the preoperative health professional to encourage total smoking cessation. For the patient about to undergo surgery, health care professionals need to stress the importance of smoking cessation and provide an explanation of the possible consequences of not stopping smoking. Box 2-4 provides examples of the type of educational information that may be provided to patients preoperatively by health care professionals.