Powerlessness

Faye I. Hummel

This was the first time … When I woke up the other morning I couldn’t get out of bed. I couldn’t believe it … my body, my legs, they just wouldn’t move. I was terrified. I thought I’d had a stroke or something. I called for John, but he didn’t hear me. I just had to lie there, staring at the ceiling, trying to calm myself. I felt so helpless, so powerless. There was nothing I could do but wait for John to come … he helped me into the bathtub where the warmth of the water soothed my aching body. I’ve always been able to handle my never ending pain … the stiffness and rigidity of my body, but that morning … that morning was different … and now I wonder.

—Anne, 62-year-old woman with fibromyalgia and Parkinson’s disease

INTRODUCTION

Chronic illness changes one’s sense of self and one’s sense of time. Living with chronic illness requires one to adapt to a continuous changing of outlooks in which the existence of dualities, such as hope and despair, self-control and loss of power, dependence and independence, can elicit feelings of ambiguity, anxiety, and frustration (Delmar et al., 2006). Chronic illness creates threats to well-being and produces multidimensional changes and challenges for the individual and family. Whether these changes occur suddenly or over a long period, chronic illness requires that individuals and families deal with and adapt to an unrelenting altered reality. Managing real and perceived powerlessness is significant. Lack of control and the incapacity to act and change may dominate everyday life for persons with chronic illnesses. Accepting and acknowledging one’s limitations as a result of chronic illness may result in a sense of helplessness and loss, as evidenced in the case of Anne:

Last week I watched John working in our garden … we have planted a garden for years together. I can’t work outside anymore … I miss getting my hands in the dirt. I had to quit my job too. I was an accountant for years … I really miss my work, my friends; we shared so much. Now … now my body is just not able. I have so much pain … constant … pain is ever with me. My body seems foreign to me … I’m losing control of my body. It takes me the better part of the day to get around, to take care of myself … I try to cook for us and keep house. I try to plan ahead but I’m just not able to do what needs to be done … I don’t have a choice. John has to do more around the house now … I’m not much help.

The Phenomenon of Powerlessness in Chronic Illness

At some point in the course of chronic illness, individuals experience powerlessness. Powerlessness in the absolute sense is the inability to affect an outcome; the inability to have agency in one’s own life (Miller, 2000). Powerlessness may be a real loss of power or a perceived loss of power. For some persons, the feelings of powerlessness may be short lived; whereas for others, they are persistent.

What and who determines powerlessness and what factors facilitate powerlessness? The natural history of chronic illness is highly variable and does not conform to a predictable course of events. The uncertainty of chronic illness, the exacerbation of symptoms, failure of therapy, physical deterioration despite adherence to treatment regimens, side effects of drugs, iatrogenic influences, depletion of social support systems, and the disintegration of the client’s psychological stamina can all contribute to powerlessness (Miller, 2000). Chronic illness results in a pronounced loss of functioning over time, disrupts social roles and activities, and limits fulfillment of role expectations (Beal, 2007). Fatigue and inability to participate and engage in social activities contribute to social withdrawal (Asbring, 2001; Beal, 2007) and loss of relationships. Loss of employment, social contacts, and physical and mental function can contribute to disempowerment of individuals with chronic illness. The quintessence of ill health is powerlessness (Strandmark, 2004).

Powerlessness occurs when an individual is controlled by the environment rather than the individual controlling the environment. Therefore, powerlessness is a situational attribute (Miller, 2000). In Anne’s story, she experiences powerlessness in part because of the degenerative nature of her disease. Despite her previous life successes, Anne now feels powerless over her own circumstances. Although Anne experienced physical limitations associated with her chronic conditions for a number of years, she was able to successfully adapt and respond to the slow progressive deterioration of her physical condition. Anne maintained power and control over her daily life. When she began to experience the crushing effects of her illness symptoms and physical limitations, Anne felt a loss of control, a sense of powerlessness. No longer was Anne able to maintain her veneer of normalcy, nor was she able to sustain her work and home obligations. Anne resigned from her job, and she struggled to keep up with her household demands. When Anne begins to consider herself without worth in terms of social norms and expectations, feelings of powerlessness arise. Her autonomy and existence are threatened. Over time, Anne becomes exhausted from fatigue and grief and feels powerless over her life situation (Strandmark, 2004). Dorothy Johnson was one of the first individuals to explore the concept of powerlessness in nursing. Johnson (1967) defined powerlessness as a “perceived lack of personal or internal control of certain events or in certain situations” (p. 40) and urged nurses to take into account the concept of powerlessness inasmuch as nursing interventions would not be effective, particularly health education, if the client felt powerless. The work of Miller (1983, 1992, 2000) has also been instrumental in the development of the concept of powerlessness in chronic illness. Miller (1983, 1992, 2000) differentiates powerlessness from similar constructs, including helplessness, learned helplessness, and locus of control. Helplessness and locus of control are based on a reinforcement paradigm; whereas powerlessness is an existential construct (Miller, 2000). Miller (2000) categorizes locus

of control as a personality trait as opposed to powerlessness, which is situationally determined. Locus of control refers to the degree to which people attribute accountability to themselves (internal control) such as personal behavior or characteristics versus uncontrollable forces (external control) such as fate, chance, or luck (Rotter, 1966). The physical and psychosocial outcomes of seeking and gaining control over chronic illness have been the focus of research by social scientists for decades. Locus of control and the beliefs of individuals about whom and what controls their lives are linked to physical and psychological health (Bandura, 1989).

of control as a personality trait as opposed to powerlessness, which is situationally determined. Locus of control refers to the degree to which people attribute accountability to themselves (internal control) such as personal behavior or characteristics versus uncontrollable forces (external control) such as fate, chance, or luck (Rotter, 1966). The physical and psychosocial outcomes of seeking and gaining control over chronic illness have been the focus of research by social scientists for decades. Locus of control and the beliefs of individuals about whom and what controls their lives are linked to physical and psychological health (Bandura, 1989).

Chronic illness erodes individual control, and this loss of personal control results in powerlessness. Progressive physiologic changes resulting from chronic illness may limit mobility and/or diminish cognitive abilities. The progressive nature of chronic illness limits possibilities and opportunities to exert control over daily life events as well as plans for the future. Chronic illness sharply delineates the nature and quality of control, often resulting in a sense of powerlessness in individuals and their families.

Chronic illness disrupts personal control and changes life activities and expectations. Maintaining personal control is important for persons with chronic illness; lack of self-management and inability to predict the course of their disease can be distressing. Decision making to manage and control everyday life with a chronic illness is complex and bound to individually constructed lives (Thorne, Paterson, & Russell, 2003). Perceptions of control are associated with greater levels of psychosocial well-being while perceptions of powerlessness are associated with poorer health and psychosocial outcomes (Hay, 2010). Persons with inflammatory bowel disease reported personal control required maintaining a balance between what one could control versus what one needed to control for everyday life (Cooper, Collier, James, & Hawkey, 2010). Using grounded theory methodology, Pihl-Lesnovska, Hjortswang, Ek, and Frisman (2010) interviewed 11 persons with Crohn’s disease. Dominant themes that emerged from their analysis of the data included quality of life, self-image, confirmatory relations, powerlessness, attitude toward life, and a sense of well-being.

Rånhein & Holand (2006) conducted a hermeneutic-phenomenologic study of women’s lived experience with chronic pain and fibromyalgia. Themes of powerlessness, ambivalence, and coping emerged from interviews with 12 women with fibromyalgia. The stories of these women revealed their struggles to manage and control the severe symptoms of their disease and their efforts to reduce their feelings of powerlessness that surfaced with pain, fatigue, and immobility. Individuals with chronic illness who develop effective systems for controlling their most severe symptoms have a more positive outlook and a lessened sense of powerlessness. The main challenge of women with chronic pain is to maintain a sense of control of self and pain in order to avoid becoming discouraged. In a theory synthesis, Skuladöttir and Halldorsdöttir (2008) postulate that women with chronic pain face multiple challenges and the threat of demoralization. However, interactions with healthcare providers may be either positive or negative. Positive interactions can result in empowerment in which a sense of control is maintained. Negative interactions can disempower clients and eliminate a sense of control over self and the situation.

Persons with health failure experience increasing powerlessness (Falk, Wahn & Lidell, 2007). A systematic review of 14 qualitative research studies conducted with older adults found that living with chronic heart failure was

characterized by physical limitations and stressful symptoms, feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness, and social and role interruptions (Yu, Lee, Kwong, Thompson, & Woo, 2008). Aujoulat, Luminet, and Deccache (2007) conducted interviews with 40 individuals with various chronic conditions and asked them to discuss their experiences of powerlessness. They found that powerlessness extends beyond medical and treatment issues to feelings of insecurity and threats to their social and personal identities. Desperation and powerlessness were expressed by women with long-term urinary incontinence. Women who lacked control of their urinary incontinence reported their autonomy was threatened, which promoted a sense of powerlessness to control their own bodies (Hägglund & Ashlström, 2007).

characterized by physical limitations and stressful symptoms, feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness, and social and role interruptions (Yu, Lee, Kwong, Thompson, & Woo, 2008). Aujoulat, Luminet, and Deccache (2007) conducted interviews with 40 individuals with various chronic conditions and asked them to discuss their experiences of powerlessness. They found that powerlessness extends beyond medical and treatment issues to feelings of insecurity and threats to their social and personal identities. Desperation and powerlessness were expressed by women with long-term urinary incontinence. Women who lacked control of their urinary incontinence reported their autonomy was threatened, which promoted a sense of powerlessness to control their own bodies (Hägglund & Ashlström, 2007).

The phenomenon of powerlessness in chronic illness is a dynamic and complex issue. Powerlessness in chronic illness can be triggered by individual attributes and perceptions or stimulated by the evolving nature of the chronic disease. Powerlessness is inherent and impending in chronic illness. However, feelings of powerlessness recede and advance throughout the course of the chronic illness as individuals negotiate between control and loss and navigate the changing landscape of their daily realities. Variables such as the degree of physical limitation and ability to manage symptoms of chronic illness can also influence an individual’s experience with powerlessness.

The Paradox of Powerlessness in Chronic Illness

The paradox of powerlessness in chronic illness is that power and powerlessness exist simultaneously. Power takes for granted powerlessness and vice versa (Kuokkanen & Leino-Kilpi, 2000). Power is defined as the “ability to act or produce an effect” and “possession of control, authority, or influence over others” (Merriam-Webster, 2011). Power can be enabling and enhance one’s autonomous ability and capacity. Despite the limiting effects of chronic illness and feelings of powerlessness, individuals continue to exert power and control in areas of their lives through adaptation and accommodation to their evolving abilities and selves.

Power is an individual psychological characteristic (McCubbin, 2001), a personal resource inherent in all individuals, and is the ability to influence what happens to one’s self (Miller, 2000). Seeking, getting, and preserving power is a dynamic process that reflects a human being’s ability to achieve a desired goal in the face of personal, social, cultural, and environmental facilitators and barriers (Efraimsson, Rasmussen, Gilje, & Sandman, 2003).

In the individual-oriented society of the United States, power is associated with independence and self-determination. Although we may think of power as an individual quality, in reality, power is a relational attribute. Power has no meaning in the absence of relationships with others and the context of the interaction. Power is developed and maintained in relationships. Power can restrict self-determination with forcefulness or authority by restricting the autonomy of another in personal relationships as well as hierarchical organizations (Moden, 2004). Power is a “social, political, economic, and cultural phenomenon, since all these dimensions of human societies determine who has power and what kind” (McCubbin, 2001, p. 76).

Individual power resources include physical strength and physical reserve, psychological stamina and social support, positive

self-concept, energy, knowledge, motivation, and hope (Miller, 2000, p. 8). Chronic illness can diminish these power resources. When power resources are significantly altered and affected, an individual with chronic illness may experience feelings of powerlessness. To deal with this powerlessness, persons with chronic illness should direct their energy toward their intact power resources. Power resources facilitate coping with chronic illness. Accordingly when one power resource becomes depleted, other power components may need to be developed to avert or reduce powerlessness (Miller, 2000).

self-concept, energy, knowledge, motivation, and hope (Miller, 2000, p. 8). Chronic illness can diminish these power resources. When power resources are significantly altered and affected, an individual with chronic illness may experience feelings of powerlessness. To deal with this powerlessness, persons with chronic illness should direct their energy toward their intact power resources. Power resources facilitate coping with chronic illness. Accordingly when one power resource becomes depleted, other power components may need to be developed to avert or reduce powerlessness (Miller, 2000).

Theoretical Perspectives of Powerlessness and Power

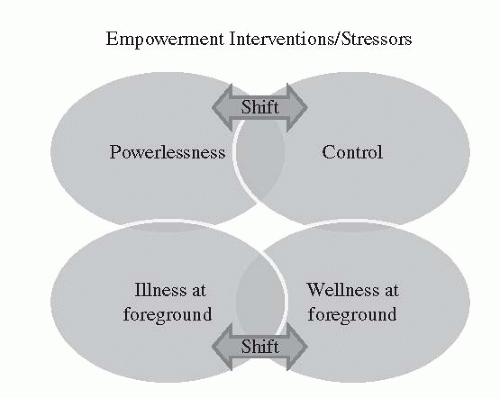

Persons with chronic illness live in a dual world, that of wellness and sickness, of control and powerlessness, and of hope and despair. The Shifting Perspectives Model of Chronic Illness (Paterson, 2001a, 2003) describes chronic illness as a complex dialectic between the individual and his or her world. This model posits that persons with chronic illness shift between the perspective of wellness in the foreground and illness in the background and vice versa. Furthermore, this model suggests that the experience of living with a chronic illness is a dynamic process that reflects the elements of both wellness and illness that comprise chronic illness. A perspective shift is a cognitive and affective strategy to negotiate the effects of chronic illness and to make sense of the experience. The perspectives of wellness and illness are not mutually exclusive, rather there is a fluctuation of the degree to which illness or wellness is in the foreground or background (Paterson, 2001a).

Rather than a static outlook, there is a continual shifting of perspectives (Paterson, 2003). Persons living with chronic illness have a preferred perspective that is assumed most frequently. Therefore, persons with an illness perspective in the foreground focus on their illness, their symptoms, and the negative impact their chronic condition has on them and others. Conversely, from a perspective of wellness in the foreground, the individual views the chronic illness at a distance and focuses on his or her abilities to navigate daily life and to perform roles and responsibilities; the negative aspects of the chronic illness recede to the background. In addition to illness and wellness, this shifting perspectives model acknowledges parallel and simultaneous contradictions in the chronic illness experience such as loss and gain, control, and powerlessness (Paterson, 2003). Hence, persons with a wellness perspective will likely exert power and control over their daily routines and social interactions.

The illness and wellness perspective is dynamic so it can be interrupted and changed at a moment’s notice. Such a shift in perspective can be stimulated by physiologic changes, events, fears, and other individuals (Paterson, 2003). Social support, competent care providers, hope, and humor are factors that influence a shift from illness in the foreground to wellness in the foreground (Freeman, O’Dell, & Meola, 2003; Haluska, Jessee, & Nagy, 2002). Exacerbations of symptoms and other forms of illness intrusiveness such as pain, decreased physical function and mobility, low self-worth, and feelings of loss of life goals and aspirations (Mullins, Chaney, Balderson, & Hommel, 2000) may shift an individual’s perspective to the disease state, and feelings of loss of control and powerlessness may arise. The “relative importance of the illness, physical experiences with the illness, and

biomedical uncertainties” (Sutton & Treloar, 2007, p. 338) can also trigger a shift in perspective. Clinical indicators of chronic disease progression may not be congruent with individual perceptions of health and illness inasmuch as health and illness views are constructed within the individual’s physical, emotional, and social spheres and may not be compatible with healthcare priorities (Sutton & Treloar, 2007). Although the focus of illness in the foreground can be selfabsorbing, this perspective may provide the individual with an opportunity to learn more about his or her illness and effective strategies to treat and manage symptoms. Figure 12-1 illustrates the shift of perspectives in chronic illness.

biomedical uncertainties” (Sutton & Treloar, 2007, p. 338) can also trigger a shift in perspective. Clinical indicators of chronic disease progression may not be congruent with individual perceptions of health and illness inasmuch as health and illness views are constructed within the individual’s physical, emotional, and social spheres and may not be compatible with healthcare priorities (Sutton & Treloar, 2007). Although the focus of illness in the foreground can be selfabsorbing, this perspective may provide the individual with an opportunity to learn more about his or her illness and effective strategies to treat and manage symptoms. Figure 12-1 illustrates the shift of perspectives in chronic illness.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

Self-determination theory (SDT) highlights the psychological processes that promote optimal functioning and health. This theory posits three basic, innate psychological needs that are the basis for optimal functioning and personal well-being. These psychological needs—competence, relatedness, and autonomy—are universal and must be satisfied for all people to achieve optimal health. These basic psychological needs provide a framework that specif ies the conditions in which people can maximize their human potential. The need for competence results in an individual’s ability to adapt to new challenges in a changing context; it stimulates unique talents of individuals and produces adaptive competencies and flexible functioning in the context of changing demands. The need for relatedness is the integration of the individual into the social world in which the individual seeks attachments, security, and a sense of belonging and intimacy with others. The tendencies of relatedness are to cohere to one’s group and to feel connection with and care of others. However, the need for relatedness can compete or conflict with autonomy. Autonomy, according to SDT, refers to self-organization and self-regulation, and conveys adaptive advantage. Autonomous individuals function and respond effectively within changing contexts and circumstances. When behavior is regulated by outside pressures and expectations, holistic functioning is precluded. Therefore, autonomous individuals are better able to regulate their actions in accordance with their perceived needs and available capacities as well as coordinate and prioritize courses of action that will maximize self-maintenance (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000).

FIGURE 12-1 Shifting Perspectives in Chronic Illness. Source: Paterson, B.L. (2001a). The shifting perspectives model of chronic illness. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33, 21-26A and Paterson, B.L. (2003). The koala has claws: Applications of the shifting perspectives model in research of chronic illness. Qualitative Health Research, 13(7), 987-994. |

Self-determination theory distinguishes between autonomous and controlled behavior regulation. Behaviors are autonomous when

persons experience a sense of choice to act out of personal importance of the behavior. Controlled behaviors, on the other hand, are those performed when persons feel pressured by external forces (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 1991). Autonomous regulation, or the choice to do what is important and relevant to the individual, is associated with subjective experiences of vitality and energized behavior and differentiated controlled and autonomous choice (Moller, Deci, & Ryan, 2006). Adjustment to chronic illness is influenced by the extent to which individuals believe themselves to be the source of their actions, that is, their feelings of autonomy (Igreja et al., 2000). Patientcentered care is grounded in self-determination theory. In Crossing the Quality Chasm, the Institute of Medicine (2001) recognizes the patient as the source of control. Patientcentered care focuses on the patient rather than the disease and gives the responsibility for disease management to the patient along with the resources and support needed to assume that responsibility.

persons experience a sense of choice to act out of personal importance of the behavior. Controlled behaviors, on the other hand, are those performed when persons feel pressured by external forces (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 1991). Autonomous regulation, or the choice to do what is important and relevant to the individual, is associated with subjective experiences of vitality and energized behavior and differentiated controlled and autonomous choice (Moller, Deci, & Ryan, 2006). Adjustment to chronic illness is influenced by the extent to which individuals believe themselves to be the source of their actions, that is, their feelings of autonomy (Igreja et al., 2000). Patientcentered care is grounded in self-determination theory. In Crossing the Quality Chasm, the Institute of Medicine (2001) recognizes the patient as the source of control. Patientcentered care focuses on the patient rather than the disease and gives the responsibility for disease management to the patient along with the resources and support needed to assume that responsibility.

Cognitive Adaptation Theory

Cognitive Adaptation Theory posits that an individual’s attempt to maintain or regain a sense of personal control may be heightened or activated by the psychological challenge that can arise out of an unpredictable illness. The heightened sense of personal control may be used as a way to maintain positive adaptation to chronic illness. An enhanced perception of control may facilitate coping with an illness-related stressor such as exacerbation of symptoms or disease progression (Taylor, 1983), whereas absence of self-control promotes dependency, powerlessness, and erodes client autonomy (McCann & Clark, 2004).

PROBLEMS AND ISSUES ASSOCIATED WITH POWERLESSNESS

There are a number of issues associated with powerlessness. Issues discussed here are examples of what individuals and their families may experience; however, it is not an all inclusive list.

Loss

From a medical viewpoint, chronic illness is comprised of physical symptoms and limitations. From a broader perspective, chronic illness brings multiple losses for individuals and their families on the physical side, but perhaps even more so on the psychological level. The diagnosis of a chronic illness may, in and of itself, represent a loss to the individual, and for some, the diagnosis of a chronic illness may be as significant as a death. The diagnosis of the chronic illness may represent the loss of hopes and dreams, income, sexual ability, physical and mental ability, quality of life, or independence (Clarke & James, 2003). The loss of mobility and agility as a result of chronic illness affects one’s ability to participate in social activities and to maintain social ties (Beal, 2007). Loss of paid employment due to chronic illness has a significant impact on one’s life. Leaving work not only results in the loss of income and daily routines but triggers a loss of positive social identity (Walker, 2010).

Persons with chronic illness have restrictions in their daily lives, experience social isolation, feel they are discounted, and fear becoming a burden to others (Charmaz, 1983). Loss of self is felt by many persons with chronic illness (Charmaz, 1983), in which the serious debilitating effects of chronic illness erode the former

self-image of the individual. Over time, accumulated loss of self-image can result in diminished self-concept. Loss of self is a result of chronic illness that diminishes control over lives and futures (Charmaz, 1983). Lack of self-confidence and disrupted identity are two major factors of powerlessness. In-depth interviews with clients with various chronic conditions revealed numerous losses including their loss of self-control and confidence as their environment and possibilities become diminished (Aujoulat, Luminet, & Deccache, 2007).

self-image of the individual. Over time, accumulated loss of self-image can result in diminished self-concept. Loss of self is a result of chronic illness that diminishes control over lives and futures (Charmaz, 1983). Lack of self-confidence and disrupted identity are two major factors of powerlessness. In-depth interviews with clients with various chronic conditions revealed numerous losses including their loss of self-control and confidence as their environment and possibilities become diminished (Aujoulat, Luminet, & Deccache, 2007).

Uncertainty

Chronic illness generates a wide array of emotions and reactions and engenders anxiety and uncertainty. The uncertainty of chronic illness promotes feelings of loss of control and a sense of powerlessness in individuals and families (Mishel, 1999). Narratives of persons diagnosed with multiple sclerosis revealed concerns about the unpredictable progression of the disease and fear and anxiety relative to the unknown (Barker-Collo, Cartwright, & Read, 2006). Severity of the illness, the erratic nature of symptomatology, and the ambiguity of symptoms promote uncertainty in persons with chronic illness (Mishel, 1999). Anticipating and planning for the future becomes complicated. The unpredictability of physical symptoms and capabilities interferes with the individual’s ability to schedule activities and events in the future and may result in an unwillingness to plan in advance. The uncertainty of the chronic illness raises salient concerns for persons about their future, about their ability to control their illness and symptoms, and their capacity to garner necessary personal and financial resources to manage their illness (see Chapter 7).

Chronic Illness Management

Chronic illness management often entails a multifaceted self-management regimen. The complexity of chronic illness has the potential to strip away a client’s sense of self-worth and confidence. Clients who lack confidence often are unable to assess their needs accurately, and consequently are at risk of being manipulated or coerced by others and may capitulate to the wishes of family members or healthcare professionals. Self-management of complex chronic disease is often difficult to achieve and is reflected in low rates of adherence to treatment guidelines (Newman, Steed, & Mulligan, 2004). Although some healthcare professionals believe they can motivate persons with chronic illness to follow a treatment regimen, the impetus to follow a plan of care is internal. Healthcare professionals must acknowledge the personal context of the chronic illness and assess the individual motivators to follow a plan of care (Singleton, 2002). Persons with a chronic illness may not be willing to or capable of carrying out the complex tasks and activities to manage their chronic illness, and a simple “pep talk” from one’s healthcare professional simply does not suffice. Clients’ realization that their days are built around their healthcare regimen —that is, specific treatments they must perform every day, doctor visits, lab tests, body scans, consults with other healthcare providers, physical therapy, and not other aspects of their lives—can become unbearable. The power to dictate how individuals with chronic illness want to spend their day is gone. For example, Mrs. Jones, an elderly widow with end-stage renal disease must spend 3 days a week at the local dialysis unit to manage her chronic illness. Even though she has accepted the time involved

to adhere to her treatment regimen and has accommodated her lifestyle accordingly, she yearns to visit her extended family that lives some distance from her. At her peril, Mrs. Jones chooses to spend time with her family, to forego prescribed treatment, and to bear the consequences of her decision. In the end, although Mrs. Jones was able to continue her dialysis treatments, her decision was motivated by her personal desire and familial priority, not the prescribed treatment.

to adhere to her treatment regimen and has accommodated her lifestyle accordingly, she yearns to visit her extended family that lives some distance from her. At her peril, Mrs. Jones chooses to spend time with her family, to forego prescribed treatment, and to bear the consequences of her decision. In the end, although Mrs. Jones was able to continue her dialysis treatments, her decision was motivated by her personal desire and familial priority, not the prescribed treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree