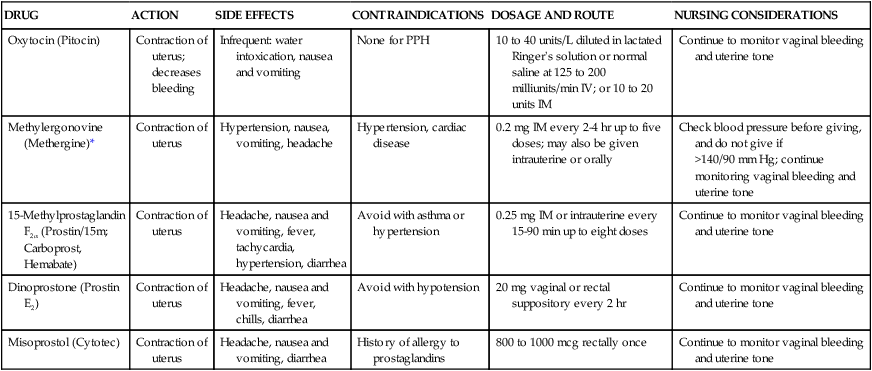

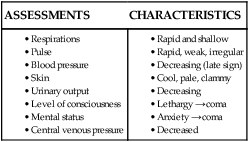

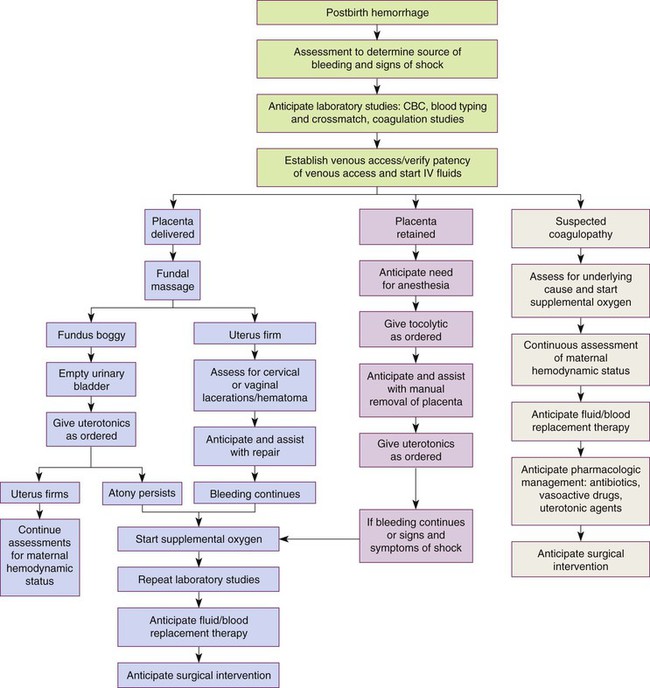

• Identify the causes, signs and symptoms, possible complications, and medical and nursing management of postpartum hemorrhage. • Differentiate the causes of postpartum infection. • Summarize the assessment and care of women with postpartum infection. • Describe thromboembolic disorders, including incidence, etiologic factors, signs and symptoms, and management. • Describe the sequelae of childbirth trauma. • Discuss postpartum emotional complications, including incidence, risk factors, signs and symptoms, and management. • Summarize the role of the nurse in the home setting in assessing potential problems and managing care of women with postpartum complications. Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) continues to be a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2006; Johnson, Gregory, & Niebyl, 2007). It is a life-threatening event that can occur with little warning and is often unrecognized until the mother has profound symptoms. PPH has been traditionally defined as the loss of more than 500 ml of blood after vaginal birth and 1000 ml after cesarean birth. A 10% change in hematocrit between admission for labor and postpartum or the need for erythrocyte transfusion also has been used to define PPH (Francois & Foley, 2007). However, defining PPH is not a clear-cut issue. The diagnosis is often based on subjective observations, with blood loss often being underestimated by as much as 50% (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, Hauth, Gilstrap, & Wenstrom, 2005). Traditionally, PPH has been classified as early or late with respect to the birth. Early, acute, or primary PPH occurs within 24 hours of the birth. Late or secondary PPH occurs after 24 hours and up to 6 to 12 weeks postpartum (ACOG, 2006; Francois & Foley, 2007). Today’s health care environment encourages shortened stays after birth, thereby increasing the potential for acute episodes of PPH to occur outside the traditional hospital or birth center setting. Considering the problem of excessive bleeding with reference to the stages of labor is helpful. From birth of the infant until separation of the placenta the character and quantity of blood passed may suggest excessive bleeding. For example, dark blood is probably of venous origin, perhaps from varices or superficial lacerations of the birth canal. Bright blood is arterial and may indicate deep lacerations of the cervix. Spurts of blood with clots may indicate partial placental separation. Failure of blood to clot or remain clotted indicates a pathologic condition or coagulopathy such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (Francois & Foley, 2007). Excessive bleeding may occur during the period from the separation of the placenta to its expulsion or removal. Commonly, such excessive bleeding is the result of incomplete placental separation, undue manipulation of the fundus, or excessive traction on the cord. After the placenta has been expelled or removed, persistent or excessive blood loss is usually the result of atony of the uterus or inversion of the uterus into the vagina. Late PPH may be the result of subinvolution of the uterus, endometritis, or retained placental fragments (Francois & Foley, 2007). Risk factors for PPH are listed in Box 23-1. Uterine atony is marked hypotonia of the uterus. Normally, placental separation and expulsion are facilitated by contraction of the uterus, which also prevents hemorrhage from the placental site. The corpus is in essence a basket weave of strong, interlacing smooth-muscle bundles through which many large maternal blood vessels pass (see Fig. 2-3). If the uterus is flaccid after detachment of all or part of the placenta, brisk venous bleeding occurs, and normal coagulation of the open vasculature is impaired and continues until the uterine muscle is contracted. Uterine atony is the leading cause of PPH, complicating approximately 1 in 20 births (Francois & Foley, 2007). It is associated with high parity, hydramnios, a macrosomic fetus, and multifetal gestation. In such conditions the uterus is “overstretched” and contracts poorly after the birth. Other causes of atony include traumatic birth, use of halogenated anesthesia (e.g., halothane) or magnesium sulfate, rapid or prolonged labor, chorioamnionitis, and use of oxytocin for labor induction or augmentation (Francois & Foley). PPH in a previous pregnancy is a predominant risk factor for recurrent PPH (Kominiarek & Kilpatrick, 2007). Lacerations of the perineum are the most common of all injuries in the lower portion of the genital tract. These lacerations are classified as first, second, third, and fourth degree (see Chapter 12). An episiotomy may extend to become either a third- or fourth-degree laceration. Pelvic hematomas may be vulvar, vaginal, or retroperitoneal in origin. Vulvar hematomas are the most common. Pain is the most common symptom, and most vulvar hematomas are visible. Vaginal hematomas occur more commonly in association with a forceps-assisted birth, an episiotomy, or primigravidity (Francois & Foley, 2007). During the postpartum period, if the woman reports a persistent perineal or rectal pain or a feeling of pressure in the vagina, a thorough examination is made. However, a retroperitoneal hematoma may cause minimal pain, and the initial symptoms may be signs of shock (Francois & Foley). Abnormal adherence of the placenta occurs for reasons unknown, but it is thought to result from zygotic implantation in an area of defective endometrium such that no zone of separation is present between the placenta and the decidua. Attempts to remove the placenta in the usual manner are unsuccessful, and laceration or perforation of the uterine wall may result, putting the woman at great risk for severe PPH and infection (Cunningham et al., 2005). • Placenta accreta—slight penetration of myometrium by placental trophoblast • Placenta increta—deep penetration of myometrium by placenta Bleeding with complete or total placenta accreta may not occur unless separation of the placenta is attempted. With more extensive involvement, bleeding will become profuse when removal of the placenta is attempted. Cesarean hysterectomy is indicated in approximately two thirds of women. If future fertility is desired, uterine conserving techniques may be attempted. Blood component replacement therapy is often necessary (Francois & Foley, 2007). Inversion of the uterus after birth is a potentially life-threatening but rare complication. The incidence of uterine inversion is approximately 1 in 2500 births (Francois & Foley, 2007), and the condition may recur with a subsequent birth. Uterine inversion may be partial or complete. Complete inversion of the uterus is obvious; a large, red, rounded mass (perhaps with the placenta attached) protrudes 20 to 30 cm outside the introitus. Incomplete inversion cannot be seen but must be felt; a smooth mass will be palpated through the dilated cervix. Contributing factors to uterine inversion include uterine malformations, fundal implantation of the placenta, manual extraction of the placenta, short umbilical cord, uterine atony, leiomyomas, and abnormally adherent placental tissue (Francois & Foley). The primary presenting signs of uterine inversion are hemorrhage, shock, and pain in the absence of a palpable fundus abdominally. The initial management of excessive postpartum bleeding is firm massage of the uterine fundus (Hofmeyr, Abdel-Aleem, & Abdel-Aleem, 2008). Expression of any clots in the uterus, elimination of any bladder distention, and continuous IV infusion of 10 to 40 units of oxytocin added to 1000 ml of lactated Ringer’s or normal saline solution also are primary interventions. If the uterus fails to respond to oxytocin, a 0.2-mg dose of ergonovine (Ergotrate) or methylergonovine (Methergine) may be given intramuscularly to produce sustained uterine contractions. However, administering a 0.25-mg dose of a derivative of prostaglandin F2α (carboprost tromethamine) intramuscularly is more common. It can also be given intramyometrially at cesarean birth or intraabdominally after vaginal birth (Francois & Foley, 2007). Prostaglandin E2 (Dinoprostone) 20 mg vaginal or rectal suppository and rectal (800 mcg to 1000 mcg) administration of misoprostol also are used (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2006). (See Medication Guide for a comparison of drugs used to manage PPH.) In addition to the medications used to contract the uterus, rapid administration of crystalloid solutions or blood or blood products or both will be needed to restore the woman’s intravascular volume (Francois & Foley). Oxygen can be given by nonrebreather face mask to enhance oxygen delivery to the cells. A urinary catheter is usually inserted to monitor urine output as a measure of intravascular volume. Laboratory studies usually include a complete blood cell count with platelet count, fibrinogen, fibrin-split products, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time. Blood type and antibody screen are initiated if not previously performed (Cunningham et al., 2005). If bleeding persists, bimanual compression may be considered by the obstetrician or nurse-midwife. This procedure involves inserting a fist into the vagina and pressing the knuckles against the anterior side of the uterus and then placing the other hand on the abdomen and massaging the posterior uterus with it. If the uterus still does not become firm, manual exploration of the uterine cavity for retained placental fragments is implemented. If the preceding procedures are ineffective, surgical management may be the only alternative. Surgical management options include vessel ligation (uteroovarian, uterine, hypogastric), selective arterial embolization, and hysterectomy (Cunningham et al., 2005; Francois & Foley, 2007). If the uterus is firmly contracted and bleeding continues, the source of bleeding still must be identified and treated. Assessment may include visual or manual inspection of the perineum, vagina, uterus, cervix, or rectum and laboratory studies (e.g., hemoglobin, hematocrit, coagulation studies, platelet count). Treatment depends on the source of the bleeding. Lacerations are usually sutured. Hematomas may be managed with observation, cold therapy, ligation of the bleeding vessel, or evacuation. Fluids and blood replacement may be needed (Francois & Foley, 2007). Uterine inversion is an emergency situation requiring immediate recognition, replacement of the uterus within the pelvic cavity, and correction of associated clinical conditions. Tocolytics (e.g., magnesium sulfate, terbutaline) or halogenated anesthetics may be given to relax the uterus before attempting replacement (Francois & Foley, 2007). Medical management of this condition includes repositioning the uterus, giving oxytocin after the uterus is repositioned, and treating shock (Francois & Foley). Treatment of subinvolution depends on the cause. Ergonovine, 0.2 mg every 4 hours for 2 or 3 days, and antibiotic therapy are the most common medications used (Cunningham et al., 2005). Dilation and curettage may be needed to remove retained placental fragments or to debride the placental site. PPH may be sudden and even exsanguinating. The nurse must therefore be alert to the symptoms of hemorrhage and hypovolemic shock and be prepared to act quickly to minimize blood loss (Fig. 23-1 and Box 23-3). Immediate assessments, nursing diagnoses, expected outcomes of care, and interventions are listed in the Nursing Process box: Postartum Hemorrhage. Discharge instructions for the woman who has had PPH are similar to those for any postpartum woman. In addition, the woman should be told that she will probably feel fatigue, even exhaustion, and will need to limit her physical activities to conserve her strength. She may need instructions in increasing her dietary iron and protein intake and iron supplementation to rebuild lost red blood cell (RBC) volume. She may need assistance with infant care and household activities until she has regained strength. Some women have problems with delayed or insufficient lactation and postpartum depression. Referrals for home care follow-up or to community resources such as support groups may be needed. (See Nursing Care Plan: Postpartum Hemorrhage.) Hemorrhage may result in hemorrhagic (hypovolemic) shock. Shock is an emergency situation in which the perfusion of body organs may become severely compromised and death may occur. Physiologic compensatory mechanisms are activated in response to hemorrhage. The adrenal glands release catecholamines, causing arterioles and venules in the skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, liver, and kidneys to constrict. The available blood flow is diverted to the brain and heart and away from other organs, including the uterus. If shock is prolonged, the continued reduction in cellular oxygenation results in an accumulation of lactic acid and acidosis (from anaerobic glucose metabolism). Acidosis (reduced serum pH) causes arteriolar vasodilation; venule vasoconstriction persists. A circular pattern is established; that is, decreased perfusion, increased tissue anoxia and acidosis, edema formation, and pooling of blood further decrease the perfusion. Cellular death occurs. (See the Emergency box for assessments and interventions for hemorrhagic shock.) Vigorous treatment is necessary to prevent adverse sequelae. Medical management of hypovolemic shock involves restoring circulating blood volume and treating the cause of the hemorrhage (e.g., lacerations, uterine atony, or inversion). To restore circulating blood volume a rapid IV infusion of crystalloid solution is given at a rate of 3 ml infused for every 1 ml of estimated blood loss (e.g., 3000 ml infused for 1000 ml of blood loss). Packed RBCs are usually infused if the woman is still actively bleeding and no improvement in her condition is noted after the initial crystalloid infusion. Infusion of fresh-frozen plasma may be needed if clotting factors and platelet counts are below normal values (Cunningham et al., 2005; Francois & Foley, 2007). Most interventions are instituted to improve or monitor tissue perfusion. The nurse continues to monitor the woman’s pulse and blood pressure. If invasive hemodynamic monitoring is ordered, the nurse may assist with the placement of the central venous pressure (CVP) or pulmonary artery (Swan-Ganz) catheter and monitor CVP, pulmonary artery pressure, or pulmonary artery wedge pressure as ordered (Gilbert, 2007). Oxygen is administered, preferably by nonrebreathing facemask, at 10 to 12 L/min to maintain oxygen saturation. Oxygen saturation should be monitored with a pulse oximeter, although measurements may not always be accurate in a woman with hypovolemia or decreased perfusion. Level of consciousness is assessed frequently and provides an additional indication of blood volume and oxygen saturation (Gilbert, 2007). In early stages of decreased blood flow the woman may report “seeing stars” or feeling dizzy or nauseated. She may become restless and orthopneic. As cerebral hypoxia increases, she may become confused and react slowly or not at all to stimuli. Some women complain of headaches (Curran, 2003). An improved sensorium is an indicator of improved perfusion. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring may be indicated for the woman who is hypotensive or tachycardic, continues to bleed profusely, or is in shock. A Foley catheter with a urometer is inserted to allow hourly assessment of urinary output. The most objective and least invasive assessment of adequate organ perfusion and oxygenation is urinary output of at least 30 ml/hr (Cunningham et al., 2005). Blood may be drawn and sent to the laboratory for studies that include hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, platelet count, and coagulation profile.

Postpartum Complications

Postpartum Hemorrhage

Definition and Incidence

Etiology and Risk Factors

Uterine Atony

Lacerations of the Genital Tract

Retained Placenta

Nonadherent retained placenta

Adherent retained placenta

Inversion of the Uterus

Care Management

Medical management

Hypotonic uterus.

Bleeding with a contracted uterus.

Uterine inversion.

Subinvolution.

Herbal remedies

![]() Herbal remedies have been used with some success to control PPH after the initial management and control of bleeding, particularly outside the United States. Some herbs have homeostatic actions, whereas others work as oxytocic agents to contract the uterus (Tiran & Mack, 2000). Box 23-2 lists herbs that have been used and their actions. However, published evidence of the safety and efficacy of herbal therapy is lacking. Evidence from well-controlled studies is needed before recommendation for practice can be made (Born & Barron, 2005).

Herbal remedies have been used with some success to control PPH after the initial management and control of bleeding, particularly outside the United States. Some herbs have homeostatic actions, whereas others work as oxytocic agents to contract the uterus (Tiran & Mack, 2000). Box 23-2 lists herbs that have been used and their actions. However, published evidence of the safety and efficacy of herbal therapy is lacking. Evidence from well-controlled studies is needed before recommendation for practice can be made (Born & Barron, 2005).

Nursing interventions

CBC, Complete blood cell count; IV, intravenous; s/s, signs and symptoms; uterotonics, medications to contract the uterus.

Hemorrhagic (Hypovolemic) Shock

Care Management

Medical Management

Nursing Interventions

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access