Chapter 7. Postnatal care in the community

Introduction

Adjusting to life at home with a new baby can be overwhelming (Hunter 2004). This chapter outlines some of the issues faced by new parents as they care for their babies at home, and considers how the midwife can ease this transition. It describes some of the information needs of parents and the issues that midwives need to consider during their postnatal visits. The example of ‘weighing the baby’ is used to illustrate how the midwife needs to make an individual assessment of the woman and her baby, before she undertakes what might be considered routine care.

National Service Framework

The National Service Framework (NSF) for Children, Young People and Maternity Services (Department of Health 2004), Standard 11 ‘Maternity Services’, outlined radical changes to maternity care. Traditionally, midwives had visited women following their baby’s birth for between 10 and 28 days (United Kingdom Central Council (UKCC) 1998). However, following changes to the Midwives Rules (NMC 2004:07), the postnatal period is now ‘not less than 10 days and for such longer period as the midwife considers necessary.’ The NSF (Department of Health 2004:33) reinforced this change by recommending that:

…midwifery-led services should provide for the mother and her baby for at least a month after birth or discharge from hospital, and up to three months or longer depending on individual need.

The NSF also recommended that if extra care is required for a woman, a maternity support worker could provide it. Under the supervision of either a midwife or health visitor, and having received appropriate training, this person can be part of the ‘community postnatal care team’ and be able to provide general advice on issues including feeding and hygiene. A study undertaken by King’s College (2007) concluded that maternity support workers have varied roles and have the potential to make a positive contribution to women’s care.

Transfer home

The length of postnatal hospital stay in the UK varies depending on the mode of birth. Women who have unassisted vaginal births stay in hospital an average of one day, those having an instrumental delivery one to two days, and those who have a caesarean two to four days (The Information Centre 2007). This short stay means it is essential that the woman receives sufficient information to enable her to feel confident caring for her baby. Although she and her baby are being discharged from hospital, her care is being transferred from one midwife to another – hence, ‘transfer to community care’ is a more accurate description of this event.

Before the woman leaves hospital it is important that she is reminded about some vital public health issues. These points should also be reinforced by the community midwife following the woman’s transfer home.

Baby’s sleeping arrangements

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) or ‘cot death’ accounts for the death of 340 babies each year in the UK (Foundation for the Study of Infant Deaths (FSID) 2006a). There are many steps that parents can take to minimize the risk. Box 7.1 summarizes the main points highlighted in the leaflet for parents, Reduce the Risk of Cot Death (Department of Health 2007).

Box 7.1

Minimizing the risk of sudden infant death

■ Baby should be placed on its back to sleep

■ Baby should be put to bed in the ‘feet to foot’ position

■ Do not overheat: the baby’s head should be uncovered indoors and the bedroom temperature set at 18°C

■ Provide a smoke-free environment

■ Baby to sleep in cot in parents’ room for first 6 months

■ No bed-sharing if parents are over-tired, have been drinking alcohol, taking drugs or are smokers

■ Settle to sleep with a dummy

■ Seek prompt medical advice if baby appears unwell

Back to sleep

This means that babies are put to sleep on their back, not on their front or on their side. The midwife needs to alert the woman that friends and relatives of an older generation who are also involved in the baby’s care may previously have been advised to put babies on their side and supported in this position with a rolled-up blanket or towel against their back. The woman should be advised, therefore, to pass on these recommendations to all those who will be involved in caring for the baby.

The principle behind placing the baby on its back to sleep is that this is the best position to allow the baby to lose heat, due to the larger surface area of the abdomen. When babies are on their front or wedged on their side with a blanket they cannot lose as much heat and can become too warm. Although it is important to keep babies warm, especially the newborn, a temperature of 18°C in the bedroom is adequate, covering the baby with two light blankets. It is therefore useful if parents have a thermometer they can use to show the true temperature of the baby’s environment rather than leaving this aspect of care to chance.

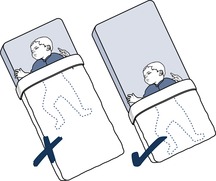

‘Feet to foot’

Placing the baby to sleep with its feet at the foot of the cot before pulling over its covers prevents him or her slipping down below them (Fig. 7.1). Although it looks strange, and not like the traditional image of the new baby in its cot, this measure could prevent the baby from dying due to suffocation or overheating.

|

| Fig. 7.1 ‘Feet to foot’ sleeping position. (From Fraser & Cooper 2003, with permission.) |

Smoke-free zone

Babies who live with parents who smoke are 30% more likely to have a cot death than babies who live in a smoke-free environment (FSID 2006b). Although it may be distressing for parents who smoke to be told this, they have the right to this information and the opportunity to alter their behaviour and that of others. If they choose to continue to smoke they should be advised not to do so in the same room as the baby and to ask visitors to leave the room if they wish to smoke.

Settle to sleep with a dummy

There is evidence to suggest that babies who go to sleep sucking on a dummy have a reduced incidence of cot death (McGarvey et al 2003). However, breastfeeding babies should not be offered a dummy until 1 month of age, to enable feeding to be well established before a teat is introduced.

No sleeping on sofa

When a baby is unsettled during the night, there is a temptation for some parents to take the baby downstairs so as not to disturb other family members. Feeding the baby on the sofa when a parent is tired is a very risky practice as there is a strong possibility that they will both fall asleep. So that the baby does not roll off the sofa, parents are likely to put the baby between themselves and the sofa back, and if the baby slips down there is a risk of suffocation. It would probably be more prudent for the parent who is trying to sleep to find an alternative bed for the night (on the sofa) than the parent whose turn it is to feed or settle the baby.

Seek medical advice

If the baby appears unwell, it is appropriate that parents are encouraged to seek medical advice, irrespective of the time of day. New parents are often concerned that they will not recognize when their baby is ill, and a few general tips can be suggested to them. The midwife can use the baby to demonstrate characteristics of good health. If the woman recognizes a healthy baby, she will soon detect when her baby is unwell.

Is the baby well?

Colour: New babies are often pale but their lips and nail beds should be pink. Some babies develop jaundice (yellow discoloration of the skin) when they are a few days old. If this happens when the baby is less than 24 hours old, parents should seek immediate medical advice. Most jaundice is physiological and provided the baby is alert and demands regular feed does not usually require treatment. The midwife will monitor babies with jaundice but parents should seek advice in between visits if the baby becomes reluctant to feed, if its skin or sclera (whites of the eyes) become more yellow or if it passes pale stools (NICE 2006).

Tone: Well babies have a flexed tone and move all limbs equally.

Behaviour: A baby that is well will demand regular feeds. It should not have a high-pitched cry, tremble or twitch. It should pass urine at least every 5 hours (Hilton & Messenger 1991) and only have loose, frequent stools if breastfeeding. Advice should be sought if the baby starts to vomit.

Temperature: The baby should be warm to the touch, but not hot or cool – the tummy is a good place to test (Department of Health 2007). Well babies do not sweat. If the woman is concerned that her baby is either too hot or too cold she can take its temperature using a thermometer suitable for use on babies (not a mercury and glass one). The normal temperature for babies is between 36.5°C and 37.2°C (Baston & Durward 2001), and advice should be sought if there is any concern, particularly if there are other signs of ill health.

Intuition: Sometimes it is difficult to put a finger on what is wrong with a baby, but if parents have any concerns they should seek advice either from the maternity service (if still under their care) or general practitioner. Out-of-hours calls are sometimes referred to NHS Direct for advice.

The first night at home

The first night at home with a new baby is an exciting new journey. The awareness that parents are alone in the house with a baby who is totally dependent on them for every need can be a stark realization and result in worry and concern. Questions will run through their minds, such as, how long will the baby sleep, will I be able to settle her/him after a feed, what if I don’t hear the baby cry? It can also be a time of utter joy, and the adoration of the new family member can take up many wakeful hours.

Midwife’s first postnatal visit

The midwife is informed by the hospital of the woman’s transfer home, and writes her name, address and birth details in her diary for a visit the following day. It is rare for the midwife to be asked to go the same day, but this may happen if, for example, the woman has gone home early with a small baby before feeding has been established or if there has been some concern that needs monitoring.

Midwives who work in the community also run antenatal clinics and undertake other duties such as parent education classes and booking interviews. Hence, midwives visits are undertaken around other commitments and the woman needs a general idea of when to expect a postnatal visit. If a long delay is anticipated, the community midwife can use her mobile phone to keep the woman informed.

After home birth

Depending on when the baby was born, the midwife will visit again to assess progress. For example, if the baby was born in the morning it might be appropriate to visit again later in the afternoon to see if the baby is demanding milk and passing urine and meconium. If the woman had her baby in the evening, she should be seen the next morning.

Student midwives in the community

For a student on the first community placement, visiting women in their own homes can be an awkward time. Not only are you having to form a relationship with your mentor, spending time together driving around the area trying to ask intelligent questions, but you are also fighting the humiliation of feeling stupid and ignorant. But fear not. Most midwives can remember vividly how they felt when they were starting out, and understand what it feels like to sit on the sofa next to a mentor, not knowing if or when to speak.

Midwifery mentors do not expect you to know the latest research on breastfeeding or how to recognize postnatal depression, but they do expect you to be polite and communicative with the woman. How good you are at this when you begin your midwifery programme will depend on your personality and previous experience. But it is a skill that you will need to develop quickly if you do not already have it. It is quite usual to feel awkward but a friendly smile and a ‘Hello, my name is Becky’ is a simple way to start. You can agree with your mentor in the car how to handle introductions. For example, the midwife introduces herself and then you say who you are and that you are working with her for the next few weeks.

As the placement progresses you will be visiting women whom you have already met at antenatal clinic. This element of continuity will quickly make you realize how important this is in community care. You will remember each individual woman’s concerns – for example, that she was worried she was carrying a huge baby and anxious about the birth. It will be interesting for you to see how labour worked out for her and how big the baby actually was (you will probably have palpated her abdomen and made an assessment yourself).

What you actually do during the visit will depend, to some extent, on the stage you are at within your midwifery programme and the learning outcomes you need to achieve. However, it will also depend on how enthusiastic you are to learn and how interested you appear. Mentors vary and you may need to be quite explicit about your learning needs. For example, if you have seen your mentor take out stitches before, you can ask her about the procedure in the car. You can then ask if she will talk you through it next time or watch you while you do it, depending on how confident you feel. The rule is that you should never do something that you have not been shown how to do, no matter who asks you. This applies to qualified midwives too (except in an emergency) (NMC 2004:16).

The morning after the night before

When the midwife and student (if applicable) arrive at the woman’s home, they introduce themselves to the family. Community midwives usually provide postnatal care for women on their own caseloads, but occasionally they visit women whom they have not previously met whose own midwives are on days off, on holiday, sick or caring for a woman in labour.

Women vary in terms of how they adjust to the additional family member. Some take it in their stride and are up and dressed the next day as if it were any other – with the baby washed, fed and dressed and sleeping soundly when the midwife arrives. In the first week the above scenario is rare. Many households take time to catch up with their new arrival and are likely to be surrounded by a plethora of equipment, visitors and evidence of the previous evening’s meal. It is quite common for the woman to spend most of her time caring for the baby and not getting round to her own shower until lunchtime.

It is important that the midwives do not pass judgment on the tidiness or otherwise of the woman’s home. We only have a glimpse into people’s lives and do not always know the full picture regarding the pressures that many women live with. However, where there is a situation that could potentially be hazardous to the health of either the woman or her baby then the midwife must address it. For example, if the room is full of smoke, parents must be strongly advised to keep areas where the baby is cared for a ‘smoke-free zone’. Or where there are animals in the house, the parents need to be reminded to make sure that the cat does not snuggle down in the baby’s pram. An experienced midwife does not look around the house reeling off a list of ‘don’t do this and don’t do that’ but, especially if the woman is one of her caseloads, will quickly build up a rapport that enables her to judge how to say what.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree