Chapter 9 Postanaesthesia recovery unit

Role and function of PARU

The PARU is a specialised area designed to care for patients in the immediate postoperative period. As discussed in Chapter 6, most anaesthetic agents have properties that have depressant effects on a number of body systems; the respiratory and cardiovascular systems are particularly vulnerable. Therefore, all patients who have received general or regional anaesthesia, or sedation, must be closely observed during the immediate postoperative period, and their condition evaluated and stabilised, with emphasis on anticipating and preventing complications resulting from anaesthesia and surgery (ACORN, 2006a).

The area is staffed by nurses and medical practitioners who are specially trained to manage and stabilise patients prior to their return to the ward or discharge home via the day surgery department. Many patients have a history of comorbidities which, when combined with the stress of anaesthesia and surgery, can affect their immediate postoperative management. The postoperative patient in the PARU is vulnerable because of altered physiological function, along with psychological and cognitive impairment. This places patients in a state of ultimate reliance on the nursing and medical staff to ensure their safety, privacy, dignity and comfort during a phase when they are unable (or inadequately able) to advocate or care for themselves (ACORN, 2006b; 2006c).

In some hospitals, particularly day surgery facilities, PARUs are often divided into stage 1 and stage 2 areas. The stage 1 area is where patients are admitted directly from the operating or procedural room and closely observed until they are haemodynamically stable and meet appropriate discharge criteria. Patients are then transferred to the stage 2 area, which consists of reclining lounge chairs, rather than beds or trolleys, and which has a more home-like environment to encourage a sense of wellness and normalcy, but where the patients can still be observed until they are ready to be discharged home (Burden, 2008). The history of the development of PARUs, which were originally called recovery rooms, is outlined in Box 9-1.

Box 9-1 History of PARUs

During the 1950s and 1960s, intensive care units were established to provide specialised care of these critical patients and recovery wards began to be purpose-built to assist in the recovery of the increasing numbers of postoperative and postanaesthesia patients. Then, as now, these areas assisted in reducing preventable deaths and morbidity, particularly from airway complications (Hughes, 1982).

PARU design features

The majority of PARUs, particularly in larger, tertiary (or referral) hospitals, function as independent areas with their own staff within the operating suite environment, providing care for patients who have undergone a range of surgical procedures under various anaesthesia techniques. In smaller hospitals, with only one or two operating rooms, and which generally cater for less complex operative procedures, staff may be multiskilled in all the perioperative roles. Regardless of the size, such areas are still required to have monitoring and resuscitation equipment to manage postoperative patients (ACORN, 2006b; Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists [ANZCA], 2006a).Figure 9-1 shows a typical PARU that could be found in Australia or New Zealand.

The location and design of the operating suite should provide for quick and easy access between each operating room and the PARU to enable an immediate response by surgeons, anaesthetists and others to assist in the management of postoperative patients who develop complications, should they arise. It should be an area that promotes comfort and reduces anxiety for the postoperative patient; therefore, design features, such as indirect lighting, soft colours, good ventilation and soundproofing to reduce noise, should be considered (Hamlin, 2005). The three most critical design features of the PARU are:

The PARU is a semi-restricted area within the operating suite, although it is important that health care workers in street clothes can access the PARU directly to consult on or provide patient care if required. However, external access into the PARU should be limited as much as practical to reduce the transfer of microorganisms into this semi-restricted area. Hospital policy will dictate whether PARU staff should wear operating suite attire (ACORN, 2006b).

The space allocated to a patient bay, which will accommodate a patient’s bed/trolley, should be at least 9 square metres, with easy access to the patient’s head (ANZCA, 2006a), at least 1.2 metres between each patient’s bed/trolley, and a specially designated area for the isolation of infectious patients when the need arises (Centre for Health Assets Australasia [CHAA], 2006). To accommodate PARU patients during peak periods, the number of allocated beds/trolley spaces within the unit should be at least 1.5 spaces per operating room; in other words, a four-room operating suite should have six PARU bays available (ANZCA, 2006a).

Patient transfer from operating room to PARU

Although the anaesthetist will determine the patient’s position for transfer, the supine position with the head slightly raised is a favoured position for the transportation of unconscious patients as this allows maximum observation of the patient’s airway and conscious state. If there is a risk of vomiting, the patient may be transported in a lateral position with the trolley/bed in a head-down tilt. Portable emergency equipment (e.g. oxygen, suction and ventilation devices such as ventilating bag and mask) is essential and must be present/available during transfer to the PARU, regardless of the procedure or anaesthetic (Ball, 2008).

Handover of care

The nursing handover should include, but not be limited to:

Additional specific patient care details, which are extremely useful to the PARU nurses, may include

The anaesthetist handover should include, but not be limited to:

All documentation and follow-up information related to the patient’s anaesthetic, surgical intervention and ongoing management must be present at handover and clarification sought by the PARU nurse when required. Postoperative surgical requirements are usually documented by the surgeon as part of the operation record and should be examined to ascertain any special orders pertaining to drains, dressings or catheters, and any special observations or other postoperative actions required (Ball, 2008).

Patient management in PARU

Initial PARU patient management

A member of the anaesthetic team is required to remain with the patient until the PARU nurse assigned to the patient is available to receive handover, take over care of the patient and is satisfied that the patient’s condition is stable (Hegedus, 2003).

On taking over a patient’s care, PARU nurses will immediately position themselves at the head of the patient’s bed, preferably behind it and the patient, to allow quick and easy access to the patient’s airway and also to emergency equipment, such as oxygen and ventilating equipment, which is usually wall mounted. An initial assessment is made of the patient’s airway, breathing and colour (ABC) and if it is apparent that the patient is unable to maintain her or his own airway, then the nurse must remain with the patient and provide airway support. A second nurse may assist by assessing and documenting blood pressure, pulse, oxygen saturation level and the patient’s level of consciousness and pain status, all of which are priorities at this time (ACORN, 2006a; Ball, 2008)

Patient observations and monitoring

Once these initial patient care priorities are met and the patient is able to maintain his or her own airway, a more thorough patient assessment can be undertaken following a ‘head to toe’ approach, which includes wound status and type of dressing, location of drains and nature of any drainage, presence of catheters, any IV fluids being given and temperature measurement. If necessary, comfort measures, such as the use of warm blankets, can be initiated. Assessment of pain status and the presence of postoperative nausea and vomiting can be made and interventions commenced where necessary (see pp 226 and 233).

Other observations include the patient’s consciousness level and, where indicated, the ECG rhythm is monitored and displayed continuously. Assessment of ABC and vital signs continue at appropriate intervals in a stable patient according to standard requirements and individual hospital policy. Unstable patients will require more frequent and prolonged assessment and documentation according to individual patient condition (ACORN, 2006a; ANZCA, 2006a, 2006b).

Assessment of airway and breathing

Look

Assessment of the patient’s airway includes looking at the following:

Listen

Assessment of the patient’s airway includes listening to the following:

Monitoring airway and respiratory function

Apart from visual observation of the patient, non-invasive monitoring of the arterial oxygen saturation level is carried out using a pulse oximeter. A detailed description of pulse oximetry is given in Chapter 6. Determination of oxygen saturation via the use of pulse oximetry is a mandatory observation carried out in the PARU and a reading of 98% is normally anticipated in the postanaesthetic patient (O’Brien, 2008).

Circulation

The effects of surgery and the side-effects of anaesthetic agents are both powerful stimulators of the stress response, which can have dramatic effects on a patient’s circulation (Desborough, 2000). Circulatory assessment includes:

Blood pressure

Blood pressure is usually measured using non-invasive blood pressure equipment, either manually or using an automated device.The patient’s preoperative blood pressure readings should be noted to provide a baseline and assess whether postoperative readings are within normal limits. A blood pressure reading 20% above or below the patient’s normal reading may be considered abnormal and can be attributed to a number of factors (e.g. haemorrhage and resultant hypovolaemic shock) (O’Brien, 2008).

Temperature control

While it is common practice to monitor vital signs such as blood pressure and pulse, monitoring the patient’s temperature is often overlooked. It is important to take active measures to assess the patient’s temperature and maintain normothermia. The issues related to the importance of monitoring for hypothermia and hyperthermia during the anaesthetic phase were discussed in Chapters 4 and 6. This must continue while the patient is in the PARU.

Assessment of temperature

Assessment of the patient’s temperature can be made using tympanic, axillary or oral thermometers, although the latter may be impractical due to airway equipment and may render a lower reading than other routes (Drain & Odom-Forren, 2008). In many PARUs the tympanic route is the route of choice to monitor temperature as it is easy to use, non-invasive, non-traumatic and provides an accurate assessment of core temperature. The aim is to maintain the patient’s temperature within the range 36.5–37.5°C and to provide comfort warming measures for a patient with a normal temperature but who feels cold. Patients who have a temperature below 36.5°C may require active warming measures, which include forced air warming devices, warm cotton body blankets and head caps or foil thermal blankets (Good et al., 2006).

It is also important to assess the patient with a temperature above 37.5°C for the possibility of malignant hyperthermia, and seek advice and assistance immediately if this condition develops (O’Brien, 2008).

General comfort measures

Although assessing and monitoring the patient’s physiological status is paramount in the immediate postoperative period, providing comfort and reassurance is also important during this time. As part of the ’head to toe’ assessment, any soiled sheets or gown should be removed and the patient made clean and as comfortable as possible. Psychological care is important as the patient may be anxious about the outcome of surgery, and the presence of a nurse speaking gently, reassuring and reorientating the patient to time and place can be very comforting. Mouth care and providing ice chips to suck will be appreciated by the patient. Some PARUs allow family members to visit, particularly for paediatric patients, where the presence of a family member may reduce patient anxiety and make the child feel more secure (Hamlin, 2005; O’Brien, 2008).

Postanaesthesia complications

Airway and breathing complications

The effect of anaesthetic agents and relaxant drugs is to depress the central nervous system, resulting in potentially life-threatening postanaesthesia complications. These drugs are the main cause of airway obstruction in the PARU (Younker, 2008). Therefore, the initial patient assessment on admission to the PARU is to determine airway patency. If obstruction has occurred, immediate action is required to identify the cause, remove it if possible and maintain the patient’s airway (Hegedus, 2003). The most common causes of airway obstruction are the tongue falling backwards into the oropharynx and the presence of secretions, such as mucus, blood or vomitus (Hamlin, 2005).

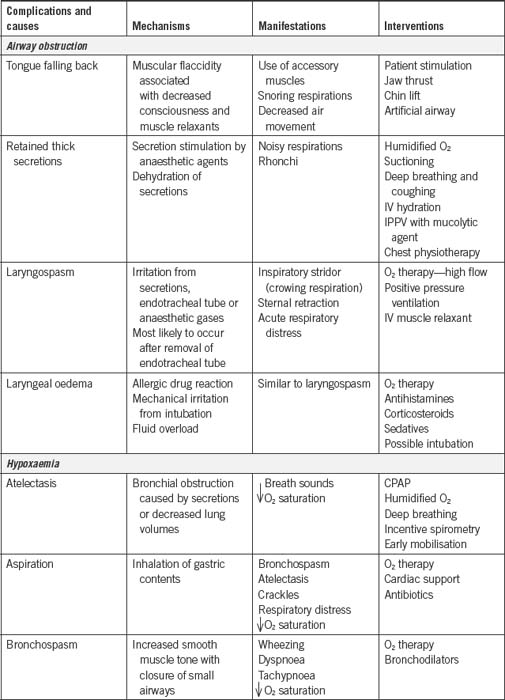

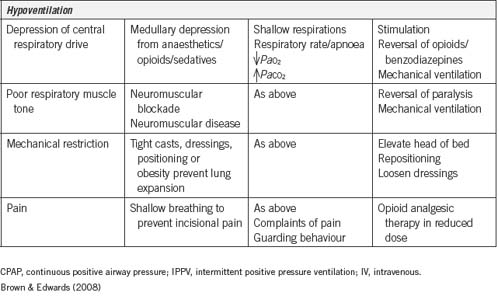

Table 9-1 summarises the common postoperative respiratory complications seen in the PARU.

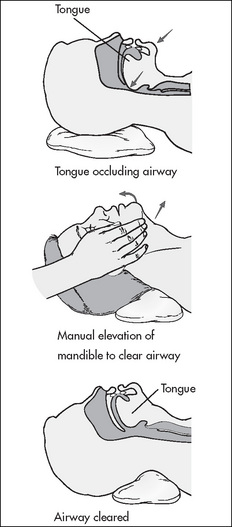

Obstruction by the tongue

Management is chin support and/or the instigation of the jaw thrust manoeuvre (Fig 9-2); the jaw thrust manoeuvre lifts the soft palate away from the pharyngeal wall, opening the airway (Younker, 2008). Additionally, the insertion of an artificial airway (oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal) can be used to maintain an open airway. The patient must not be left unattended during this period until the PARU nurse is confident that the patient is able to maintain his or her own airway. Patients can also be repositioned on their side in the recovery position as this action will assist in moving the tongue forward and relieving the obstruction (Drain & Odom-Forren, 2008).

Obstruction by secretions

Laryngospasm

Laryngospasm is one of the most serious life- threatening airway complications. It is the partial or complete closure of the vocal cords in response to stimulation by secretions such as mucus, vomitus or blood, vigorous suctioning of the airway or inappropriate placement of an artificial airway, which touches the vocal cords (Mahajan, 2007).

The patient may also suffer a total laryngospasm when the vocal cords close completely. In this situation, there is no sound and no air entry into the lungs, although the patient will still be making efforts to breath characterised by exaggerated chest movements. These patients will rapidly become hypoxic and then unconscious (Drain & Odom-Forren, 2008).

Management of total laryngospasm includes:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree